History is not only the record of major events; it is the slow accumulation of ordinary lives moving through everyday circumstances. During Carnival, for a brief stretch of days, the ordinary steps aside and the improbable takes command.

For me, photography is an instrument of confrontation—with the world, with others, and with time. It was from this understanding that I began Brazil in Transit, a project I have been building over many years, one that repeatedly leads me to places where the country becomes most visible. Carnival is one of those places.

I have always photographed people. What draws me are faces, bodies, gestures—presence itself. When it works, the image ceases to be merely a portrait and becomes a clue: an indication of who we are and how we inhabit the world.

There is no shortcut to understanding Brazil without looking at those who inhabit it. Landscape helps, architecture too, geography explains much—but nothing replaces a face. In the end, Brazil begins and ends with people.

It may sound obvious. It isn’t.

Consider how the country so often appears elsewhere: as an idea, a stereotype, a caricature. People become numbers, statistics, headlines—rarely individuals.

My path has always moved in the opposite direction: starting from the individual as a way of approaching the collective.

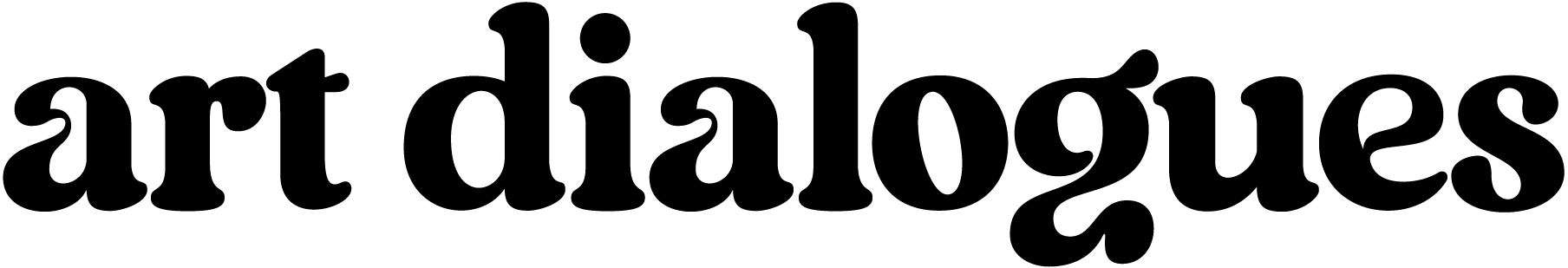

This way of seeing did not arrive fully formed; it was shaped on the road. Over more than twenty years working in the audiovisual industry—across films, series, and documentaries—I traveled Brazil from top to bottom: from capitals to small towns, from asphalt to dirt paths, from forest to backlands. I’ve been to places where the State arrives late, if at all. On many of those journeys, I carried a 1963 Rolleiflex with me, almost like an amulet.

Whenever a face struck me, the old camera came out of the bag—between shots, during a break, at the end of a filming day, on a day off. Photographing became a way of preserving those encounters with Brazil.

At first, it was pure impulse. Later, I realized the images were forming something larger. They were small fragments of Brazil—and together, they began to tell a story.

They were exercises in attention. Today, gathered together, they number in the hundreds and reveal a country in constant transformation. The Brazil of twenty years ago is already another. The Brazil of ten years ago, too. For photography, time is not an enemy; it is an accomplice.

There is a discreet ambition here: to register a country too vast to fit into a single definition. Perhaps the most plural of all.

Carnival enters this trajectory as a singular chapter.

If everyday life shows Brazil at a slow pace, Carnival reveals it at full speed—intoxicated with joy.

I chose Rio de Janeiro, my hometown—its neighboring neighborhoods, places deeply woven into my everyday life—to photograph Carnival. In truth, I photographed Rio very little over these twenty-five years. “A prophet is not recognized in his own land,” the saying goes. I decided to challenge it, imposing on myself the task of looking for the extraordinary within my own landscape.

And Rio does not disappoint.

The street I walk down every day, hurried and distracted, suddenly changes character. It fills with bodies nearly naked, covered in glitter and disproportionate joy. In a matter of days, the city sheds its skin.

Carnival has no script, no fixed form, no manual. It is organized disorder—or disordered organization—depending on the point of view. But disorder is the rule.

To photograph it is to accept that the best strategy is to keep moving. Without stopping.

Street photography is built on attention, persistence, and luck. I walk, observe, wait—again and again. Most of the time, nothing happens. The moment passes, the scene dissolves, the photograph never exists. What remains—and little remains—is what is here.

Perhaps it is this rarity that gives the images their weight.

I am economical with tools for an undertaking like this: a digital medium-format camera and a fixed lens, nothing more. Light and agile. What matters are the people. I still use the Rolleiflex in many situations, but for Carnival, digital offers speed. I leave home in the late afternoon, when the untamable tropical light begins to cast long, reclining shadows. I stay in the field for only three or four hours. It may seem brief, but the intensity is high. Intuition leads the way.

The faces I encounter during Carnival are not different from those I see the rest of the year. They are the same Brazilians—just amplified. There is fatigue and euphoria, shyness and audacity, fantasy and reality. Some want to be seen; others prefer to disappear. There is everything—there is a great deal of Brazil in Carnival. And a great deal of Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.

A portrait, when it works, explains nothing. It suggests.

We live in a time obsessed with quick answers. The photography that interests me prefers questions.

At the center of my work is dignity—even during Carnival, when people come close to losing it. Dignity is a simple word, but a demanding one. To photograph with dignity is not to turn anyone into spectacle or caricature. It is to remember that the person photographed is not a character—they are a person.

When an image works, it does not demand attention. It sustains presence.

There is a thin line between photographing someone and using someone. I stand firmly against use. What I propose is memory.

This position also shapes the form: direct framing, natural light, few tricks. Black and white appears often because it concentrates the gaze on what matters. Color enters when it is essential to communication—as in Carnival, where color often clarifies rather than complicates.

Black and white also carries a curious quality: it scrambles time. Sometimes even I cannot tell when a photograph was made. I like that. I am not interested in dated images, but in images that continue to breathe.

My background in cinema emerges unconsciously. I think about space, background, the relationship between people and their environment. Each photograph contains a small story. The difference is that in cinema, the story unfolds. In photography, it must fit within an instant.

That demands simplification—and trust in instinct.

Brazil in Transit does not aim to prove anything. It prefers to observe.

To observe that there is not one Brazil.

That there is not one Brazilian.

That radically different projects of country coexist side by side.

There is something political in this, though not partisan. Politics, here, is deciding who enters the frame and who is usually left out. By placing at the center those who rarely occupy it, I make a choice.

Carnival is one rehearsal within this broader path—just as were the Ashaninka of the Envira, the Christian faith of Aparecida, the quilombola community of Carinhanha, the hidden roots of Minas Gerais. Each experience feeds the same project.

In the end, photography is a quiet way of writing history.

There is, therefore, a clear desire to leave a trace. Not a monument. A constellation of images that, decades from now, allows someone to say: this is how they saw themselves. This is how they showed themselves. This is how they existed. This is how they celebrated Carnival.

I hope these images do not make noise.

I hope they endure.

And in a hurried world, endurance already feels like a meaningful achievement.

@dantebelluti // vimeo.com/dantebelluti

Photos: Dante Belluti