…Which is weird, because these are all photos of, let’s face it, hipsters. And the hipster’s gambit is insincerity expressed through sarcastic irony. Or it was back then. To have grown up in the nineties was to have had enough of a false sense of security as to take some comfortable critical distance from mainstream culture. Music scenes could be independent, subcultural codes still determined language, dress, and behavior. But with this participation in a proscribed alternative also came an awareness that your grasp on a scene was tenuous. The deeper you got into, say, MC5 or Fela Kuti, the more you realized how far away you were from that time and place. The 80’s, whose aesthetic was both futuristic and Fifties, ended punk and obliterated any real connection to seventies subculture. We dug through the crates of the past in the 90’s to construct our bricolage identities of snide hipster defiance.

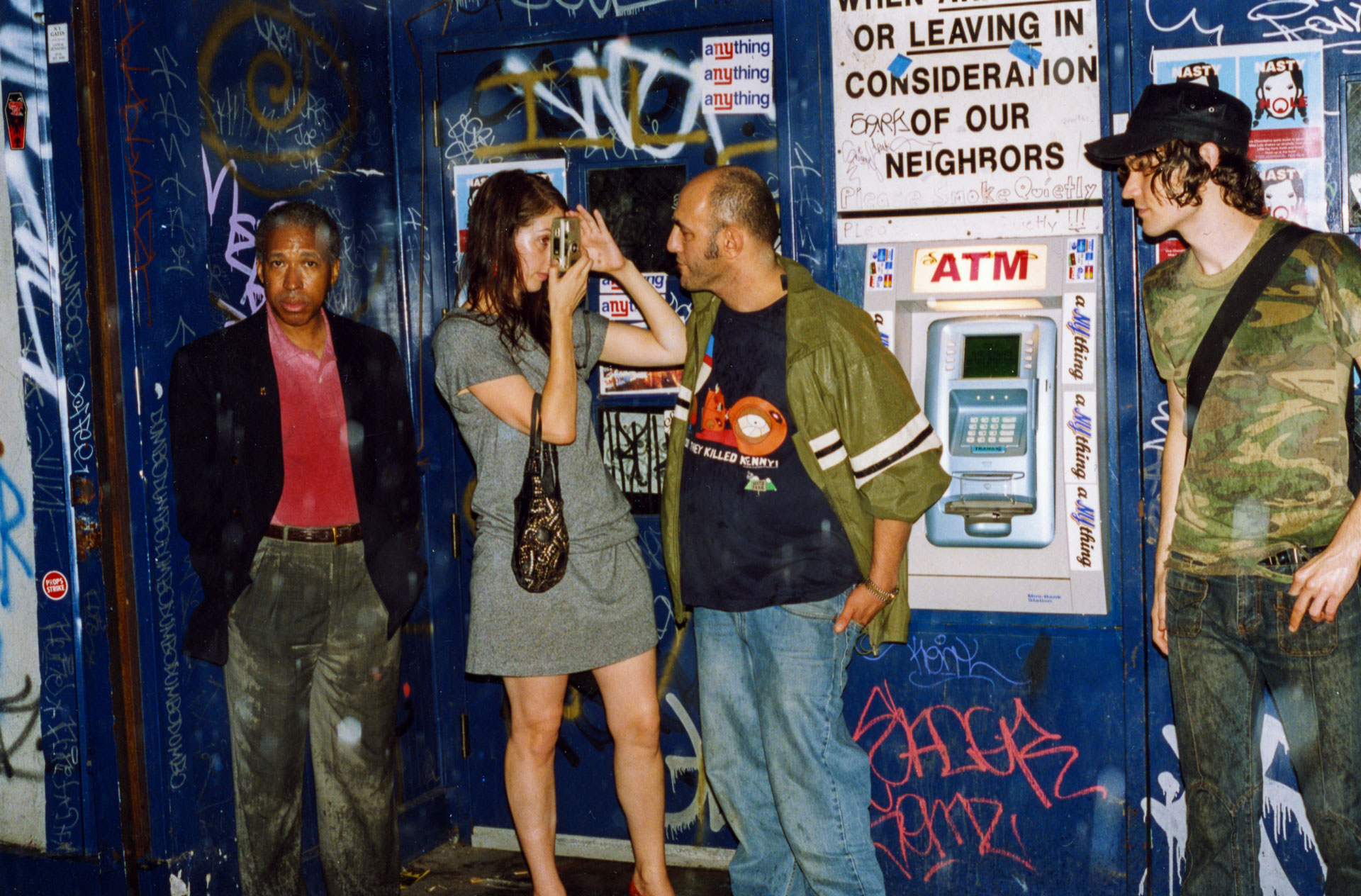

These are not photos like we see today, photos that try to convince complete strangers of how cool the photographer is by exposing whatever situation they shoot. Instead, Alain’s photos show how amazing New York can be when you’re young, new, eyes wide open to its promises of boundless potential. Of friends and strangers alike, Alain’s perspective is self-less, a non-possessive gaze that you can only have for people who will die in a place you love that will surely change.

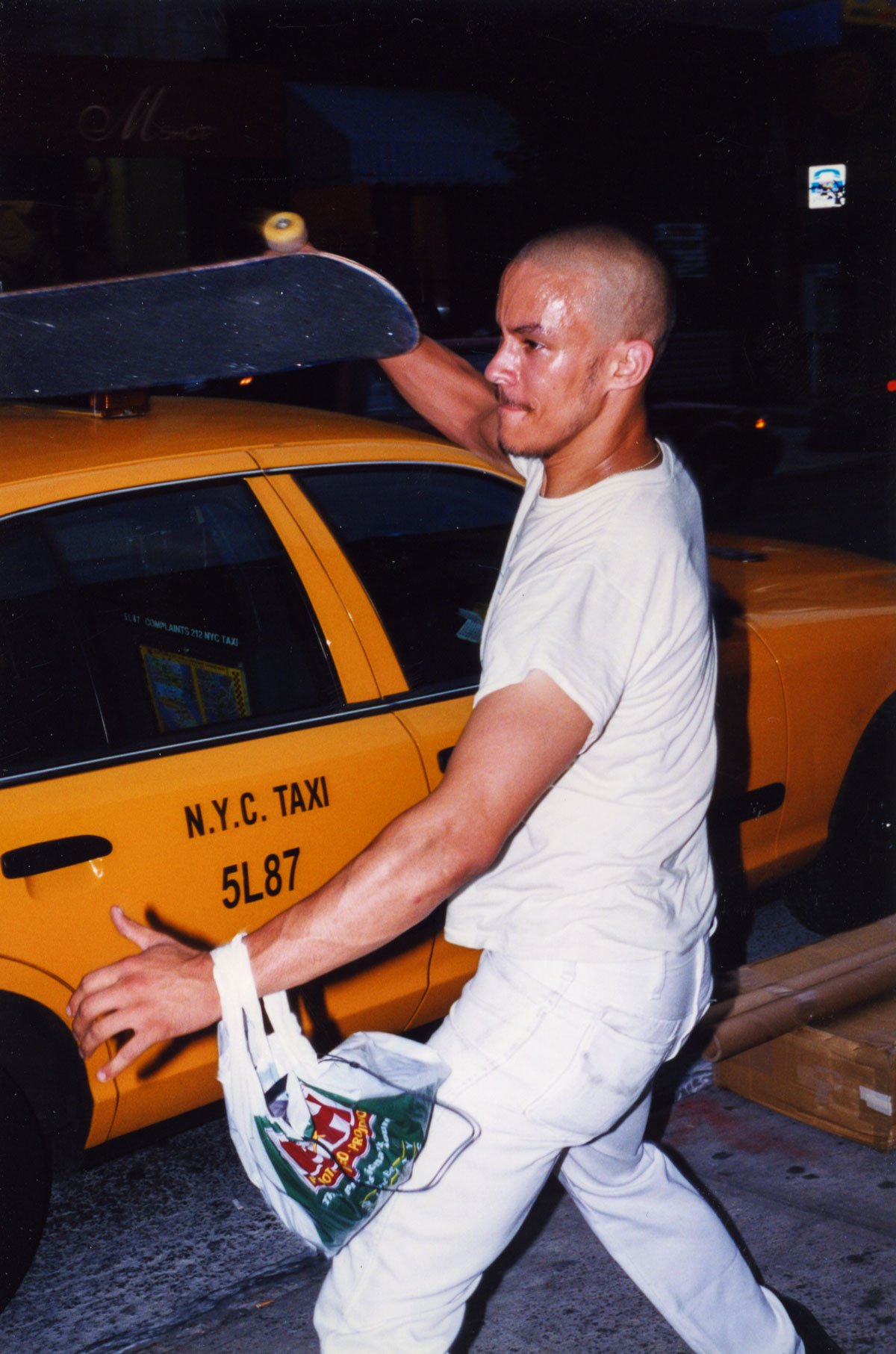

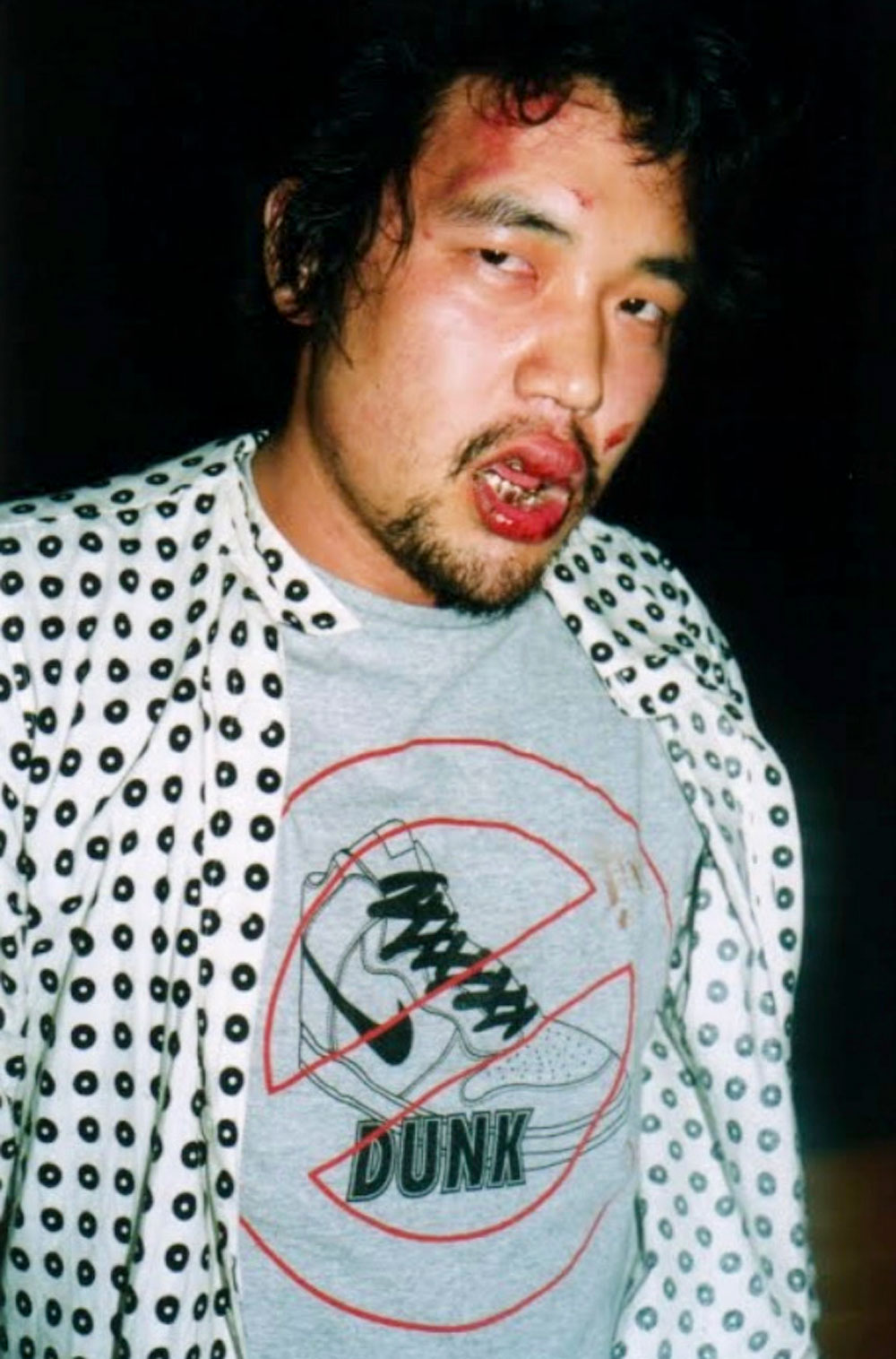

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

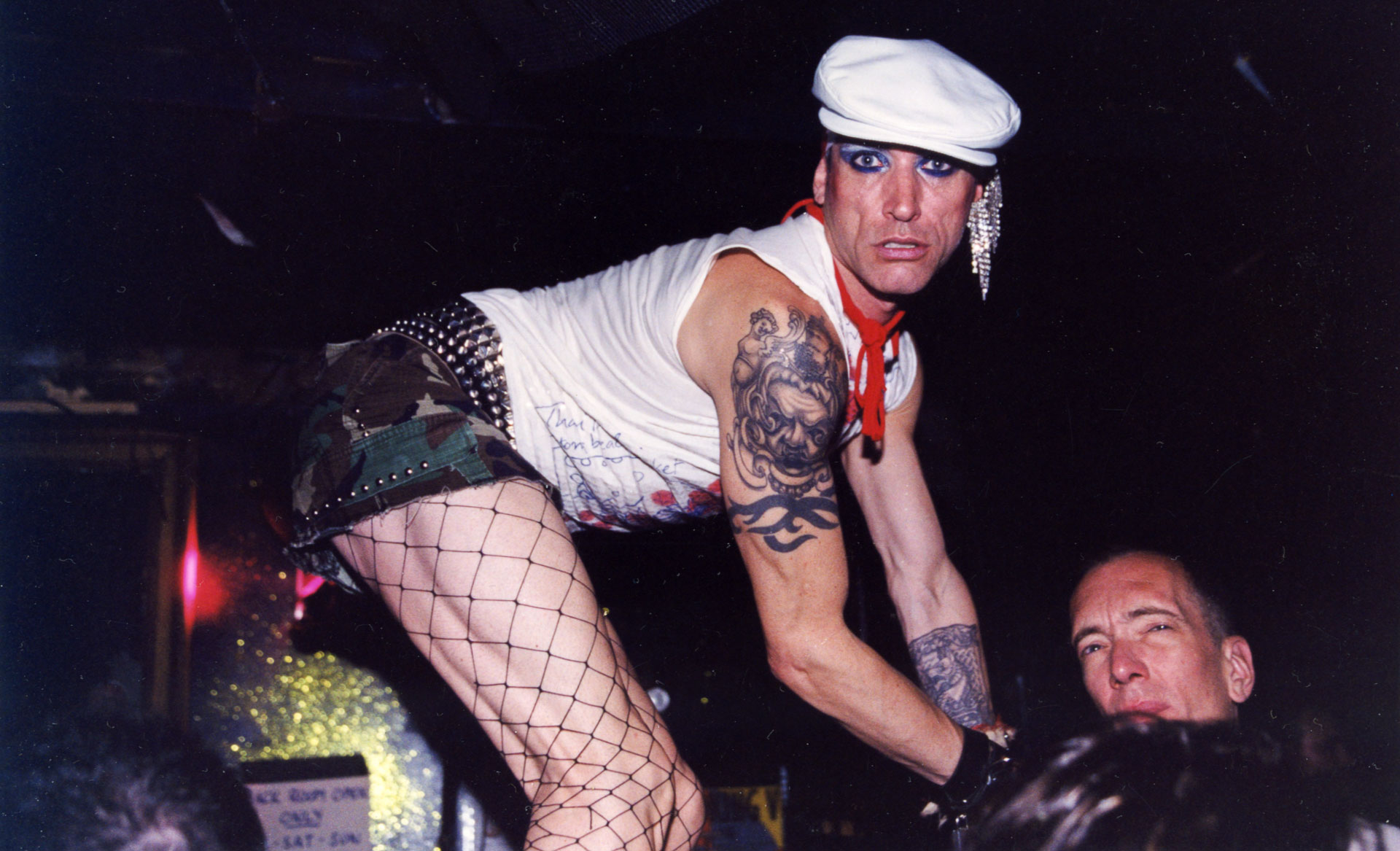

Alain moved to New York on September 28, 2000. His sister Danielle, a fashion photographer, got him a job shooting fashionable people in soho to pick-up on trends. Within a couple months, Alain was also working at FC29, aka The Fat Cock, which soon became The Hole, a mostly-gay bar that, on Wednesdays and Saturdays, had mixed and open nights. The Hole was the hub for a couple years, until it closed September of 2004. That was it.

That is genesis story for his photographs, the where, when, and why. Looking at these images now, however, they don’t resemble your typical street-style photography, party blog imagery, or fashion reporting. They are engaged, part of the scene, shot from within, a crucial difference.

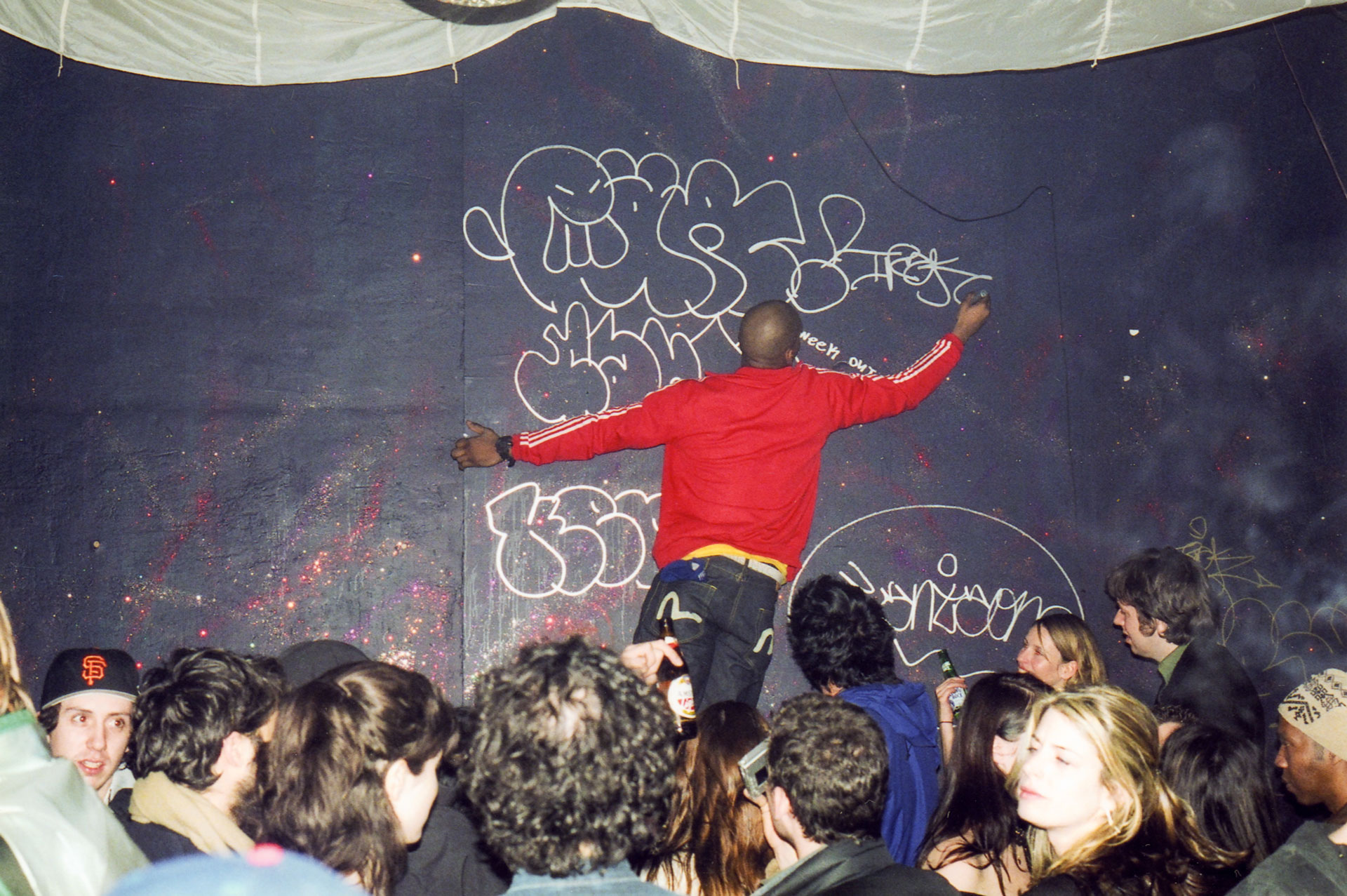

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Of course these photos are about nostalgia—not just the nostalgia one might feel looking at them now, piecing together a dissolute night in scattered flashes from the distance of many lifetimes ago–wondering about what kind of circumstances brought Ol’ Dirty Bastard or Jay-Z within the same remit as Kent (RIP) or Kenji. The subjects in these photos are also pinned between two times: how they might want to resemble past New York icons, and how might they look to future eyes. If that seems too general and—duh—obvious (that’s what everyone thinks when being photographed), let me make the case for this time and this place:

This was probably the last time when people in New York — or anywhere — posed for photos without the guarantee of instantaneous review. These photos of performed oblivion, youthful abandon, buzz between crushing insecurity and supreme ease and confidence. A lot of these kids, like me, grew up worshipping the idea of New York when it was the subcultural capital of music and art. And, for a brief moment, we felt, as all kids sometimes must, like were at the center of it, right there. Some were from there, some belonged there, and some were just thrilled to be there. And though it seemed like everyone had a camera, photos were still scarce, thus dear. Photography before the smartphone, before the party blog, before digital diaries, before the selfie. Before the endless scroll of our own insignificant past, every fucking meaningless moment replayed and archived on our shiny devices, was made part of our normal daily habit. This alone makes these photos special.

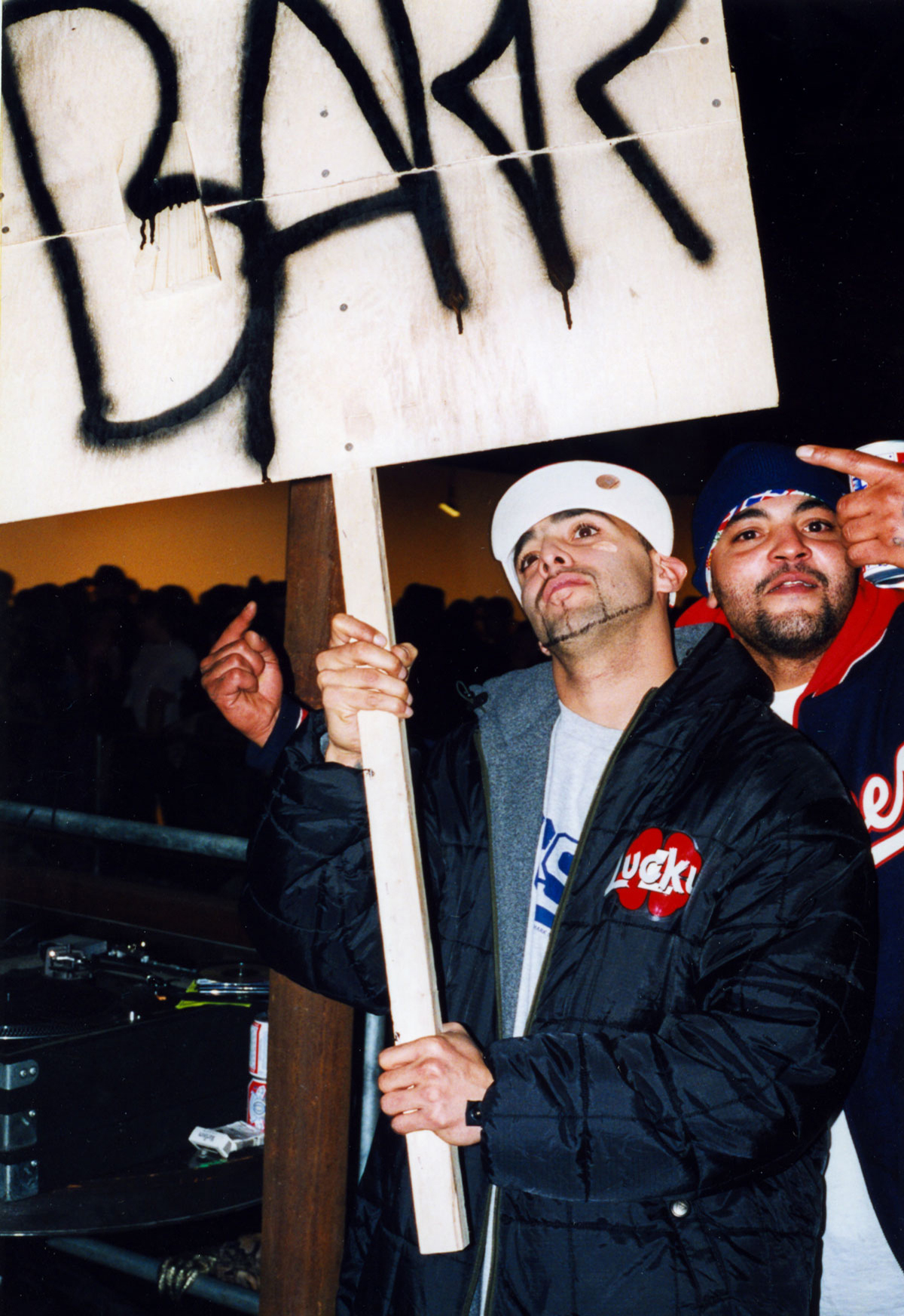

But now we are flooded with images, so what makes these worth revisiting? Well, there’s that quote from Terry Valentine, played by Peter Fonda in The Limey (2000), that goes: “Did you ever dream about a place you never really recall being to before? A place that maybe only exists in your imagination? Some place far away, half remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language. You knew your way around. That was the ’60s.” For some of us, that was the early aughts. We knew the language, we were there, but it might as well have been a dream. Alain’s photos are the culled fragments of a time and place that can’t be rebuilt or regained.

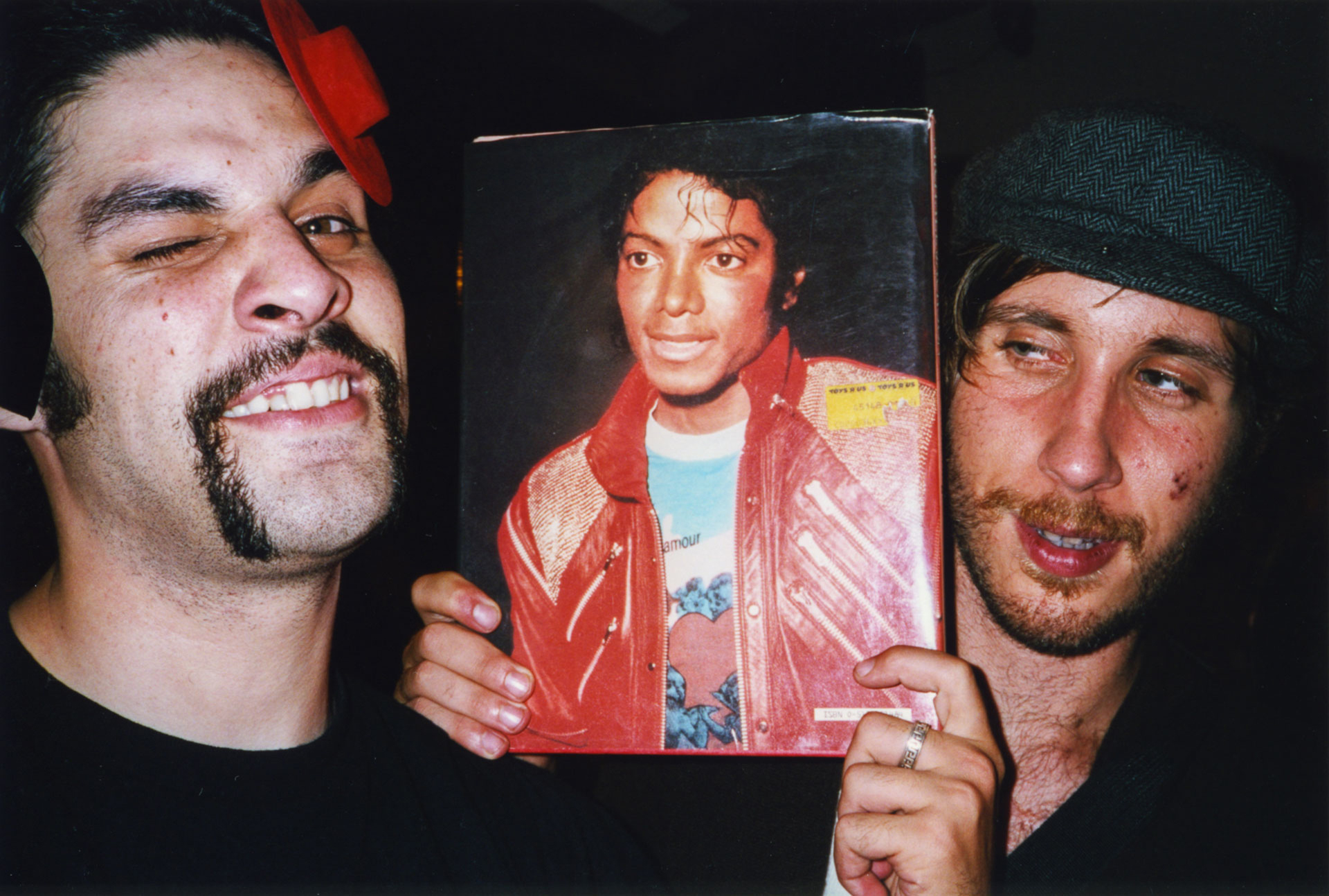

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Dash Snow, the brightly burning flame to countless moths, flickers through Alain’s photos, and many fluttered around him. In the summer of 2004, the different downtown subcultural scenes coalesced in that way that seems so specific to New York City: unplanned, disorganized, but also very intentional.

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

But, as we were soon to learn, intention only goes so far; things change. Not only did the Hole (the dark, dank bar that was the nexus of the scene) close—much to Alain’s relief—but Bush was re-elected and the stupid, ironic moment of post-9/11 New York metastasized into the mainstream. At a time when the city’s tragedy was made global, and its survival was co-opted into the government’s lies about weapons of mass destruction; the petty gangster Giuliani gave way to the absurd billionaire Bloomberg; and the construction of new condos downtown led to the conceptual expansion of Lower Manhattan into parts of North Brooklyn, which somehow made inevitable the broadcasting of North Brooklyn into the gentrifying neighborhoods of every city in the rest of the world. It all seems like some snide ironic joke that clumsily became part of our tragicomic reality today. Alongside this came the steady litany of the deaths of friends, one after the other, each year after 2004. It goes without saying that a lot of the people in these photos are drunk, are high, and some are now dead. Photography promises an eternal present-tense, but death is assumed with any photograph from the past, but it is also especially relevant to this place, this time, this group. Because we worshipped at the altar of a dead New York we only knew from old photos, it was embedded in how we lived in these now old photos.

Of course some of the subjects here are playing a role, and of course some are posing to emulate past NY heroes. Notice how, as wild and sweaty and sloppy as these photos are, the subjects pose, acknowledging the photographer. New York has a long history of producing fame around hype. The excitement of being here is knowing that this electric cycle is churning around you; you feel it pulsing through your veins and reverberating against the bricks and iron of the city, and it remains the most fabulous backdrop for culture the world has ever known. Not only has everything already been done here, but it was also documented, etched into an ever-expanding matrix of how much better it was before you got here. The special thing about New York, and this moment, is knowing that even if your scene had been played out thousands of times before by other people, that only served to make you feel part of the lineage. It is the world’s most exciting play, where the audience gets to share the stage.

Some of it looks cool, a lot of it looks sweetly dorky, and some of it just looks off. What should interest a total stranger in these photos is the awkward intimacy and vulnerability—of people trying too hard to look cool, or looking cool without even trying, whose performance of self is still raw, unmediated by the digital mirror reflection—ever constant—of today.

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Looking back at these photos now, they look less like Nan Goldin, or whoever we were trying to emulate, and more like those red-faced 17th century Dutch geselschapje: bleary drunks caught in ecstasy of youthful invincibility before the tulip market crashes.

It goes without saying that we hoped these photos would resurface but didn’t know how. Alain was part of the lawless nightlife, the last legitimate underground in Lower Manhattan, tending bar and documenting the flashes of optimistic debauchery that could still happen in a scene that hadn’t yet been invaded, in perhaps the last time when that could still happen.

And of course, the digital photo party blog bled right into more instant gratification. This meant that nostalgia was experienced with greater immediacy, now connected less to an earlier epic era (imagining how we’d look if photographed decades ago) to how we would look when our last later’d night was seen the next day by a total stranger online. An irrevocable shift occurred, and there is really no going back from that.

The more we see, the less we know. What we now see in Alain’s photos is people who still believed that to be seen was a real step toward being known. It’s hard to believe that anymore. It was naïve to believe that then. Could these parties have gone on indefinitely? Would they ever mean something after all, to anyone else, later? Maybe it’s the innocence that makes them interesting now. There is a sincerity here seldom seen today.

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

These photos are propositions, invitations, like all parties can be. Looking back, maybe we didn’t or couldn’t really know what “it” was, but, through our sometimes awkward vulnerability and other times brazen confidence, stumbled towards it. Alain captured that moment of bleary-eyed sincerity when our masks of flat hipster affect slipped. To be a hipster was to know that our grasp on the scene was tenuous, that our presence in New York was parasitic, and that our faddish aesthetic codes would soon be outmoded. And sometimes, as in these photos, none of that mattered.

Thank god Alain looked with selfless love at these never-lasting moments before they disappeared forever.

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Ted Barrow, PhD., is an art historian, skateboarder, lecturer, curator and current host of Thrasher Magazine’s series “This Old Ledge,” on Youtube. Barrow’s writing has been published in Artforum, The New York Times, Alta, Juxtapoz, and Thrasher Magazine. He lived in New York City from 2002-2020 but has never really left.

To know more about Ted: @tedbarrow

Alain Levitt, Untitled, 2000-2005. Analog photography, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

Alain Levitt was Born in Santa Monica in 1974, and grew up free-range on the west side of Los Angeles. Skateboarding, Graffiti, Raving – the trifecta of 90’s subcultures – helped inform his worldview and gave him a home amongst the outcasts. The same world he would focus his lens on after moving to New York in 2000. Not yet a photographer, Alain picked up a camera out of necessity. His first job in NY was shooting street fashion for his sister, Danielle Levitt’s, Sunday style column in the New York Post – a job that required carrying a camera 24/7. His second job, at the infamous gay bar The Cock, gave him a front-row seat to a wild NY that was quickly being choked out by Mayor Giuliani and provided enough income for this budding photographer to only work two evenings a week. Alain quickly found his community on the Lower East Side- Alife by day, Max Fish at night.

To explore more of Alain’s work: @alainlevitt