The fact that he was the first Brazilian composer in the country’s phonographic history to present an album with songs in African languages led me to develop a strong intimacy with his musical production, while also aligning myself with the thought he encapsulated in the fields of knowledge production.

This period marks my first encounter with Kingana – the proverbs in Bantu-Kongo language – and it happened in the early days of 2021 when multiple universes opened up in my mind. I became obsessed with listening to the proverbs and started using them as a tool in my courses and artistic activities. Suddenly, that instrument seemed like a guide for life, full of symbolisms and mysterious angles. And it was precisely there that my interest in reaching Tiganá’s imagination deepened, which, I felt, seemed strongly focused on the concepts of sound installations. Following the clues of his productions and observing his intents in the world, I also had the chance to appreciate his immersion in the Brazilian contemporary art scene. As I had long suspected.

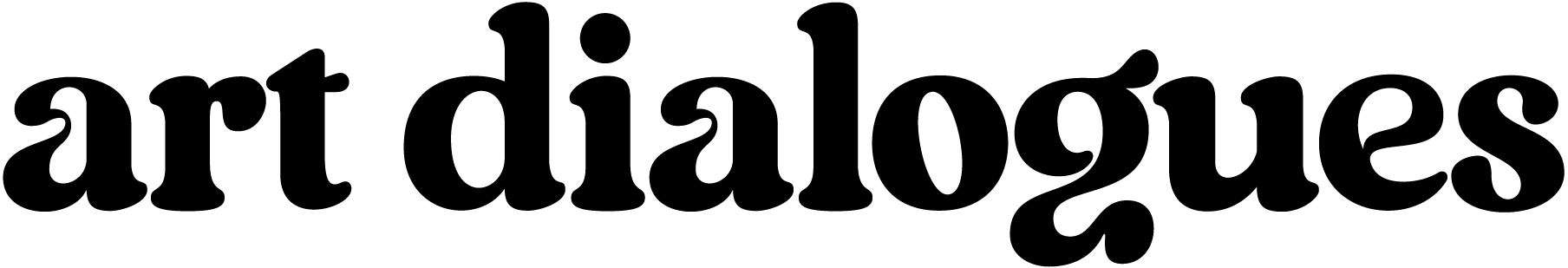

Musicians of Lindas (Race Band). Region of Kouango. Collection J. Audema. Photo: Albert Bergeret, circa 1896-1910.

Over the moons, I persistently navigated the paths that would lead me to the chance of experiencing the sound works created by the artist.

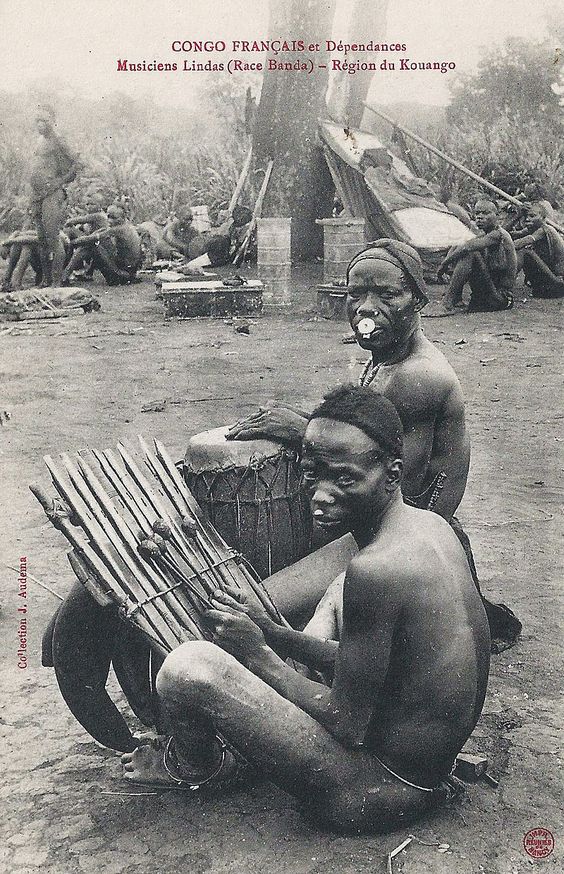

The first was “Perder a Imagem” (Itaú Cultural, 2022) which, according to Tiganá himself, “is a proposal to leave what is seen aside and feel in other ways – through hearing, touch, other senses.” The installation is based on the thoughts of the historian-poet Beatriz Nascimento – who would have turned 80 in 2022 – unfolding into a questioning of the centrality of the image itself.

In my first encounter with the work, I felt a kind of invitation to a succinct stroll through a cosmos reminiscent of uterine memories, with all its darkness and the small water pool allowing us to wet our bare feet. The possibility of feeling the ground through a path made of sounds in their infinite varieties of timbres, melodies, and harmonies. All this immediately made me, upon entering the work, leave behind all the images my eyes absorbed on the way from home to the busy Paulista Avenue – which houses the Itaú Cultural building.

“Perder a Imagem”, installation created by musician, researcher, and poet Tiganá Santana, inspired by the ideas of historian Beatriz Nascimento.

Image: André Seiti/Itaú Cultural.

I understood that the concept-ground of “Perder a Imagem” also comes from the Kongo African proverb “Wa i mona,” which states “hearing is seeing.” Based on it, Tiganá composed the theme that constitutes the essence of that space, or as he himself says, “to put it simply, the work is just a handful of frequencies.” A handful of frequencies that, in harmony with the setting, made this experience a place suspended in the air’s platform: I felt vibrations in the contemplation of curious children’s steps, intuited the slow time of the elders who knew how to walk in half-light, overheard the bubbling that radiated in the anxious gaze of the young people seeking understanding in that procession… at the end of the journey, after drying and putting on our shoes, we were still met with the drastic discomfort of the light propagating outside, intense, punishing the eyes that, consciously, had sought and sensed generous things in the darkness.

“Perder a Imagem”, installation by Tiganá Santana. Courtesy of Itaú Cultural.

Shortly after the opening of “Perder a Imagem,” I received an invitation to participate in an activity that emerged as a proposal for interaction from the work. Tiganá gathered visual artist Ayrson Heráclito, researcher Cíntia Guedes, and me for a conversation revolving around the following question:

What is an image?

The proposal was to navigate through the concept that gives name and shape to the installation, proposed by Beatriz to express the lives of enslaved Africans and their descendants in Brazil. We turned our attention to the film Ôrí, scripted by her, and also to our own experiences which, as Tiganá aptly defined, lead to “a conversation around place, absence, excess, the multiple meanings of what, above all, Euro-Western has constructed as an image,” a construction always established in visuality that does not consider “other senses, dimensions, silences.” Faced with this, the artist ponders: “If we consider cosmologies coming from the African continent, as well as those of indigenous peoples of the Americas, we must take another path of world perception.”

Image: Ophélia Agency

Our encounter was immensely powerful, filled with strange and abysmal beauties, an elegant provocation that left me with a sense of advancement, for somehow, I knew I was a bit further along in understanding Tiganá’s artistic production.

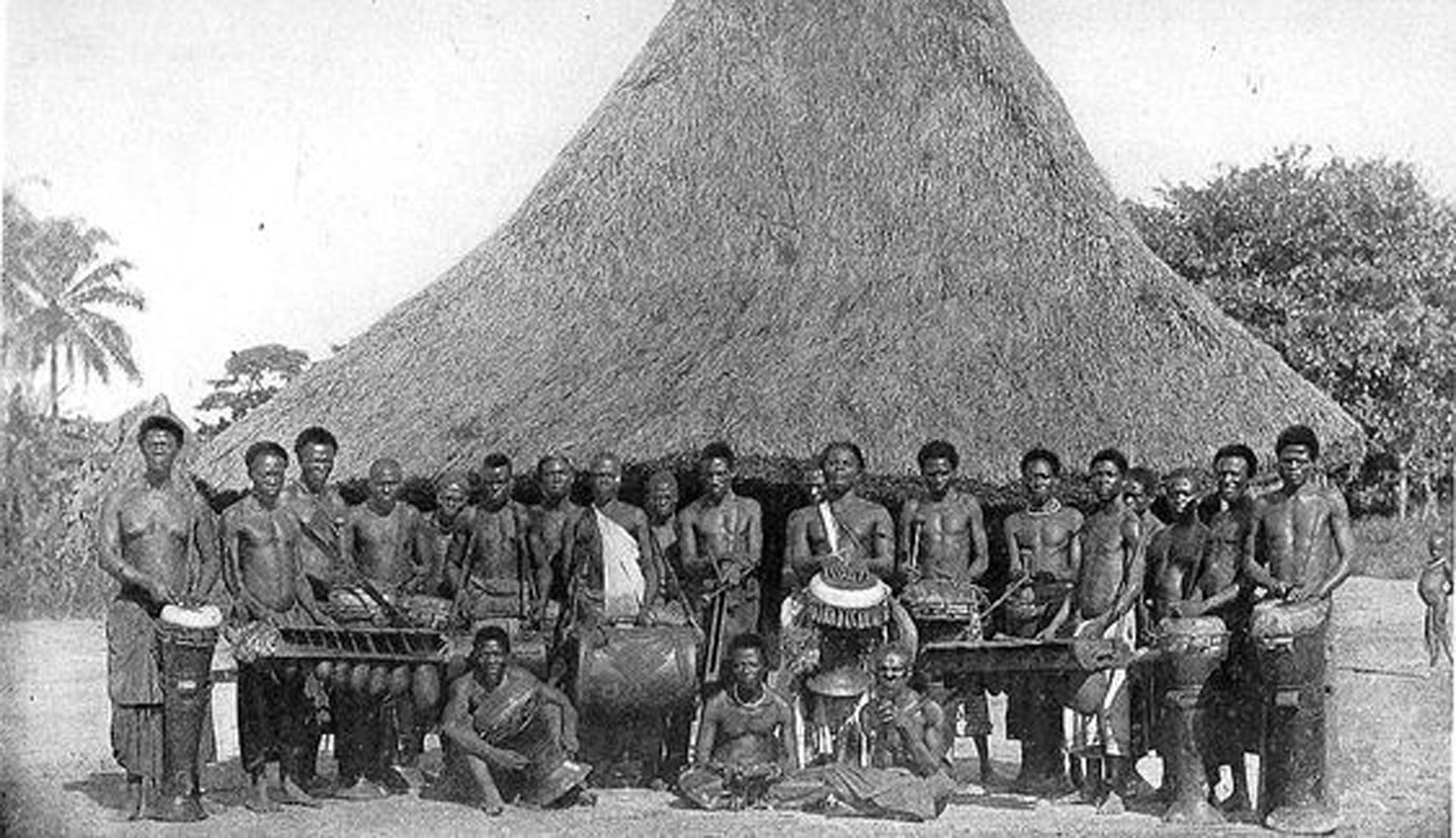

A few seasons later, it was time for the blooming of the 35th São Paulo Biennial (2023) when I delved into the taciturn labyrinths of the work “Floresta de Infinitos” (with Ayrson Heráclito), which I consider the most obscure and complex among all the artist’s installations. Covering 240 square meters, the work is shaped like a bamboo forest, guided by a path that clears through the spell-sounds pouring from the speakers, resembling the fruit of intimate encounters with the Forest Peoples. Challenging space-time, we find ourselves on a journey alongside ancestry, revering its plural manifestations and being blessed by its presences. Called “sonic-imagetic enchantments,” the music-magic born from the work makes treading the sawdust path an act of courage that, somewhere, propels us forward, even if the heart is laden with a certain apprehension of the darkness.

Darkness tends to have that effect on the body, doesn’t it?

Will it be easy to navigate the iridescent world of spirits? It was then that I realized the installation was indeed a call to perceive what inhabits layers deeper than terrestriality itself could offer us. Diving into the sound textures, as the biennial text suggests, I could feel the “breath” of the forest at different times of the day, intermittent sounds of living beings, winds, trees, rains.”

Exhibition view of the work of Ayrson Heráclito and Tiganá Santana during the 35th Bienal de São Paulo – choreographies of the impossible © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist.

Finally, as the year was coming to a close, I had the honor of accompanying part of the production of the work “Ilês, Aiyês, Carnavais e Ancestrais” (Centro Cultural Futuros Arte e Tecnologia, 2023), as a curator at the thirteenth edition of the Novas Frequências Festival. The installation proposed a celebration and remembrance of one of the most important artistic-cultural manifestations in the country, the afro bloc Ilê Aiyê, founded in Salvador in 1974 from the Candomblé terreiro, Ilê Axé Jitolu.

Composed of yellow, red, and black fabrics, printed with the bloc’s traditional symbols, the installation also includes other elements like coast palm, mats, and a ritual drum. Tiganá brings together a myriad of meanings and materials that pay tribute to Brazil’s first afro bloc in a beautiful sound piece, composed by the artist and recorded in Salvador with the participation of percussionists from the bloc and the group BaianaSystem. Experiencing the installation, I felt that the small, cozy, and colorful space invited us to bow to the drum spirit and dance in its overwhelmingly black presence. Like an initiatory chamber of otherworldly airs, it seemed to reverberate the devotion of this artist who has long known that his music is influenced by everything that crosses him. Therefore, his production, both directly and indirectly, is a translation of lived experiences. That’s why this work reaches our bodies directly as an expression of the artist’s own philosophy when he tells us, “Ilê shaped me, and that’s why I owe everything to Ilê.”

Tiganá Santana, work “Ilês, Aiyês, Carnavais e Ancestrais” (Centro Cultural Futuros Arte e Tecnologia, 2023).

After this experience, I continued my investigative mission. Now it was a fever… Darkness, experimentation, sound art, Wa i Mona… There was still much I wanted to know, I needed to understand how these concepts orbited the artist’s imagination.

This led me to many questions , so I sought to initiate a conversation to highlight the poetic and conceptual elements that drive and characterize Tiganá Santana’s creative vigor in contemporary art. The invitation from Art Dialogues for this essay provided the perfect opportunity to connect with the artist’s remarkable sensitivity, leading to the possibility of this dialogue and answers to some of my questions.

Tiganá’s relationship with sound art is deeply intertwined with his musical and artistic productions, as well as his research practice. He is fascinated by things that exist beyond the visual and the tangible. He perceives sound, like the wind, singing without revealing its body as a specific point. This possibility of inventing and creating from sound attracts him to what the Western tradition calls music. For him, composing songs and instrumental themes over the years naturally led to creating soundscapes and installations. In his essence, these concepts blend without clear boundaries – they are his ongoing creative actions. Each sound installation is thought of by Tiganá as a song or an instrumental theme, and each track recorded on an album is, for him, like a sound installation proposing landscapes. And it is in this mode of invention that he uses his research and study – his entire existential repertoire – to translate his relationship with life.

sponsored by the Petrobras Cultural Program.

Of all his installations, I was not yet familiar with the piece for the exhibition “Invenção dos Reinos” at the Oficina Francisco Brennand. The work explores the cultures of enchanted beings and various entities from Pernambuco, extending to other regions such as Maranhão and Bahia. It reflects the non-oppositional relationship between invention and reality, blending fiction and existence. For Tiganá, these entities are as real as they are fictitious—they exist as long as you believe in them and, at the same time, exist independently of your belief. He finds this dynamic fascinating and wanted to honor the place of invention, his favorite aspect of life. Attracted by the rhythmic dynamics of constancy and variation, a prevalent theme in many creations of the African diaspora, the artist composed the piece and invited Juninho Costa and Sebastião to record it, both significant collaborators. The rhythmic charge that surrounds the work aligns with the cultural territory of the exhibition, allowing for the freedom of regulation.

An explosion occurred in my mind as Tiganá’s exploration of space, time, and listening showed me his intent to make the universe of forces around us perceptible. His aesthetic strategies transform invisible forces into audible and visible experiences through the exploration of space, materials, and technologies. This curiosity leads us to the Bantu-Kongo phrase “Wa i mona,” which applies not only to the work “Perder a Imagem” but to all his creations. The dimensions of temporality, the raw material of invention, teach us that events, situations, facts, and daydreams—all children of time—are mobile, displaceable, and porous. Presence, in dark sensibilities, is not limited to the present moment but encompasses past, future, and the in-between. Creative action is a processual action of presence that encompasses the existence of the creator and what crosses him. In a world that privileges hyper-materiality and the hyper-legitimization of the visual, Tiganá warns that saying “hearing is seeing” challenges the hierarchy of the senses in perception. This Bantu-Kongo phrase encapsulates the artist’s approach to the world’s propositions: to hear the heartbeat of life and respond to the unknown with presence.

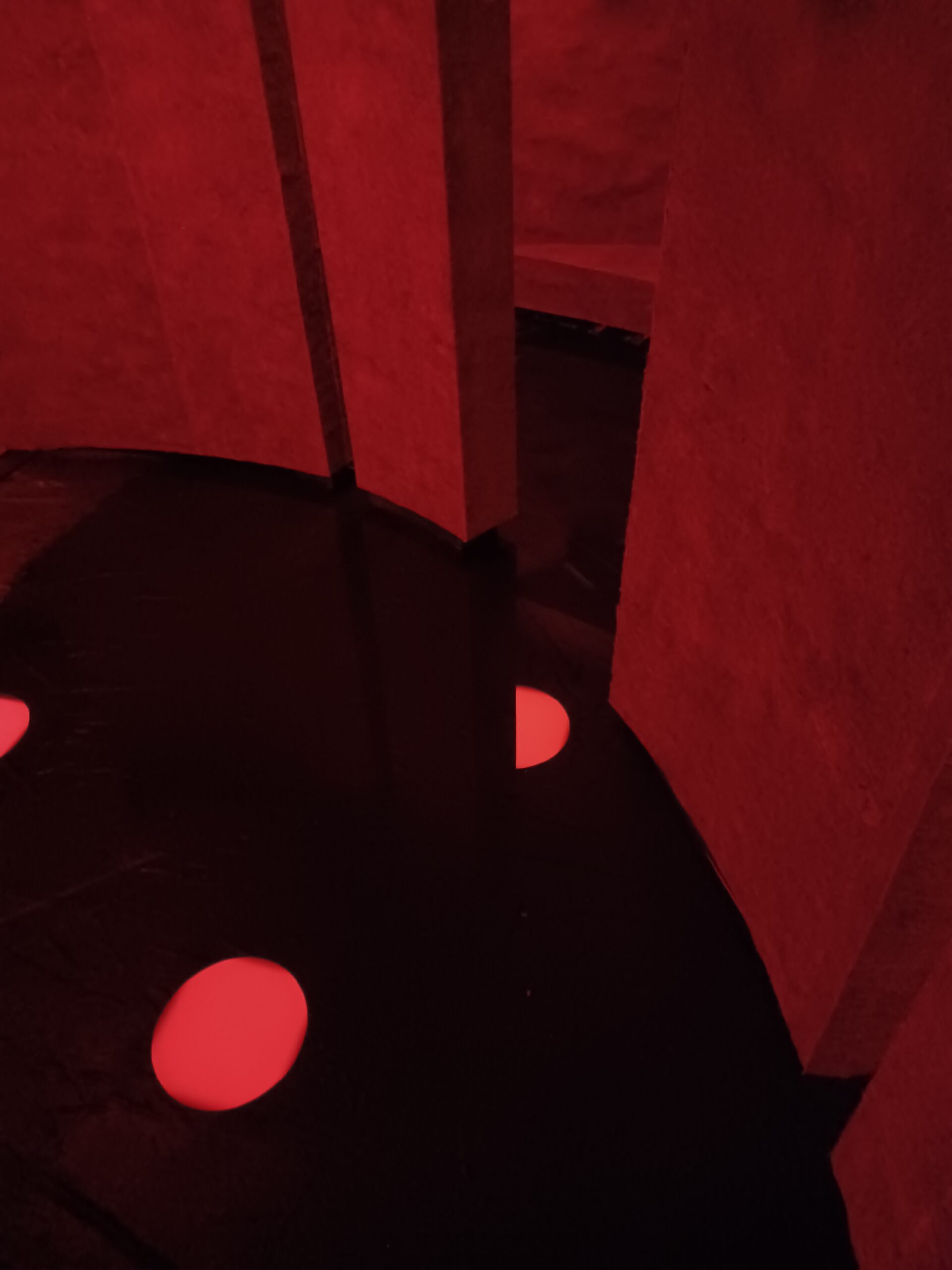

Congo musicians. Copyright: The Story of the Congo Free State; social, political and economic aspects of the Belgian system of government in Central Africa. Publication date: 1905. Publisher: New York and London, G.P. Putnam’s sons. Collection: Robarts; Toronto. Contributor: Robarts – University of Toronto.

In this sense, Tiganá perceives proverbial sayings, or Kingana, as places. He intuits a total integration between reflection, experience, research, and artistic action. The idea of performance and the implication of the body in these performances, for example, are present both in proverbial sayings and in the acts of singing or playing music. These elements aim to activate something beyond ordinary life. Mystery inhabits these performances, along with two other aspects: both the proverbial sayings and the sound installations are places where sound becomes space, and space becomes sound. These places can activate feelings, memories, and sensations of belonging. The materiality of these places is concrete, as they are spaces of settlement. Additionally, there is a dissolution of boundaries between sound, music, philosophy, and places of enunciation and announcement. For Tiganá, it is about traversing another world.

His work creates ambiguities between sound and silence, inside and outside, fear and curiosity, past and present, destabilizing the viewer and re-establishing them through the exercise of darkness. For Tiganá, darkness is an essential part of existence: the darkness of the universe, the brain, dark matter, the in-between place of events, death, the next step, the intangible, the revealed, and the absence of what once was or is yet to come. The act of manifesting has the fragility of exposure or explanation. Tiganá does not seek explanations, clarity, or comfort in his art; he aims to know the unknown better. Darkness serves as an anchoring force, with everything emerging from the unknown and returning to it. Sound appears, disappears, and merges with the unfathomable. His imagination tells us that darkness is a gesture of welcoming the things of the world.

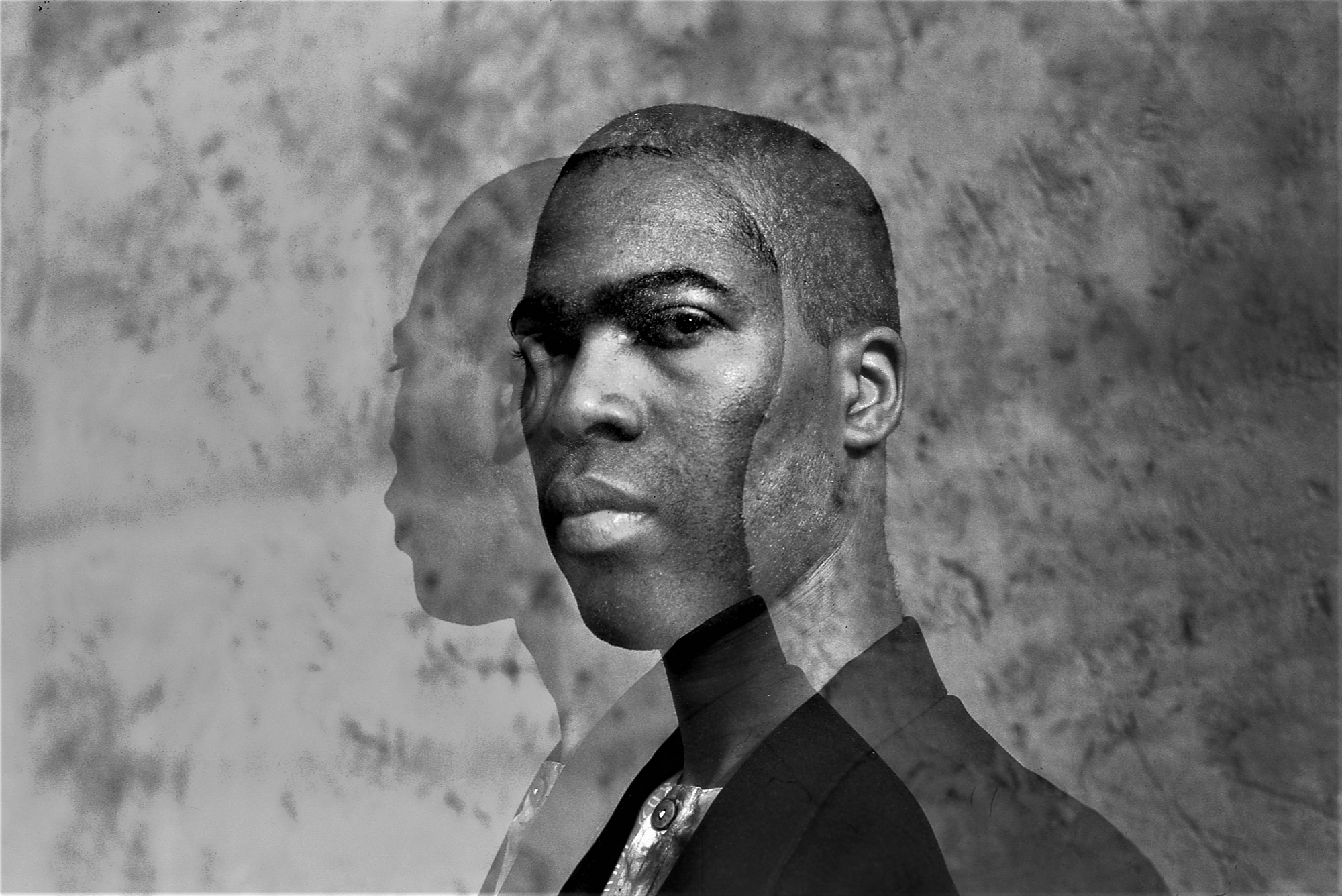

Tiganá Santana. Photo: Rodrigo Somba.

Each spatiality created by the artist offers a different experience, amplifying minute details to our perception. This sense of wonder leads visitors to interact with his work in unique ways, never appreciating it the same way twice. Experimentation plays a significant role in his journey. For Tiganá, invention inherently involves experimentation, a freedom to fly with and without the known body. He aims for sounds to be habitable or transient places and for spaces to flow in the liquidity of sound frequencies. His soul conceives the act of experimenting as recognizing and establishing encounters between materialities of distinct origins, embracing the absurd, the paradoxical, the magical, and the irrational as fruitful ways to perceive and profile the world. His process deepens, both skeptical and poetic, yielding results that dance between chance and depth, without definitive answers, gods, or science, but with the freedom to explore the impossible.

With a career spanning cultural production, arts, education, writing, and research, Nathalia Grilo’s paths revolve around Radical Black Imagination. She works as a narrative curator at the studio and pavilion of artist Maxwell Alexandre and is also a curator at HOA Gallery.

Additionally, she is part of the Levante Nacional Trovoa movement, writes about music, poetry, and visual arts for the Missa Negra column at Sobinfluência publishing. She leads the Negrume program on Rádio Veneno, sharing her studies on Black Spiritual Music. Nathalia curated the music section at the Virada Cultural de SP in 2022 and the Pulsar edital of SESC RJ in 2023. She conceptualized, produced, and curates the Ayó Encontro Negro de Tradição Oral and the Mulambo Jazzagrario Instrumental Festival.

Nathalia Grilo is a Black woman from the far south of Bahia, a migrating body, and a mother..

Born on December 29, 1982, in the city of Salvador (Bahia), composer, singer, instrumentalist, poet, music producer, artistic director, curator, researcher, professor, and translator Tiganá Santana began his musical studies in guitar at the age of 14 in his hometown with Alberto Batinga. He started composing during this period, having experienced poetic writing since the age of 9.

Over the past 13 years, Tiganá Santana has toured extensively and continuously through European, African, and Asian countries, always prioritizing intercultural encounters and collecting relevant aspects of local cultures alongside his artistic work, interpreting them in his unique way.

Simultaneously, he has disseminated his artistic works, reflections, and research through various presentations and interviews on radio, newspapers, magazines, and television, including BBC Radio in London, the French newspaper Le Monde, Carta Capital magazine, the newspapers Folha and Estado de São Paulo, A Tarde and Correio da Bahia newspapers, Rádio Cultura de São Paulo, Rádio Senado, TV4 in Sweden, Radio France Internationale, Polskie Radio (from Poland), among others.

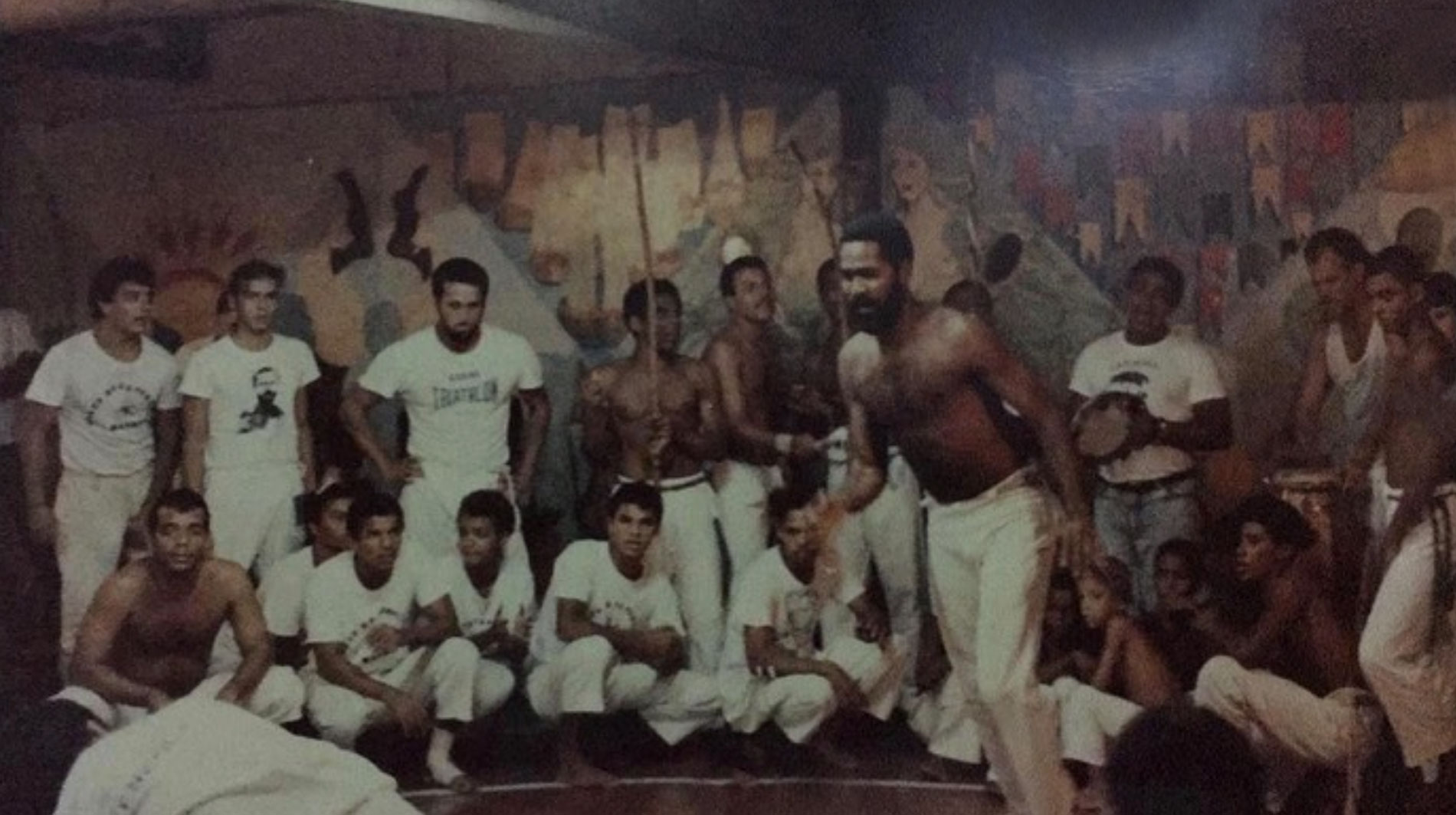

Jaime Neves Santos, Tiganá’s father, during a capoeira training.

“As an influence on my artistic practice, I feel that capoeira, which was part of my life from childhood through adolescence when I trained with my father, is another foundation of Black cultural heritage for me, much like Candomblé. I stopped practicing capoeira, but I still carry its physical memory. I think I only started reflecting on that later. For me, the influence of capoeira is most evident in the possibility of singing, because when I was a child, I used to sing the capoeira chants, the ladainhas. My father would have me sing them. That, I can truly recognize as an opening to the act of singing.”

Congo musicians. Photo: Unknown photographer.

Technical Sheet for Tiganá Santana’s Works:

Floresta de Infinitos (2023)

Sound-visual installation created by: Ayrson Heráclito and Tiganá Santana

- Atabaques: Tiganá Santana and Sebastian Notini

- Voice: Tiganá Santana

- Recording: Sebastian Notini (Itabuna Estúdio)

- Clarinet, Bass Clarinet, and Recording: Joana Queiroz (Estúdio Volante)

- Ambient Sounds Captured at Guarani Village of Rio Silveira, São Sebastião (SP): André Magalhães

- Music Production, Sound Design, Mixing, and Mastering: André Magalhães

- Exhibition Design: Stella Tennenbaum

- Lighting Design: Anna Turra

- Interaction Design and Sensor Programming: Jarbas Jácome

- Animation, Computer Graphics, and Interactive Projection: Fernando Rabelo

Image Credits:

- Mãe Stella de Oxóssi – photograph by Mario Cravo Neto/Instituto Moreira Salles

- Índio do buraco – photograph from FUNAI archive

- Dom Phillip – image created from family archive

- Bruno Pereira – image created from family archive

- Mãe Edna do Espírito Santo (Risolá de Cassarangongo) – image created from family archive

- Joãozinho da Goméia – photograph by Pierre Verger/Fundação Pierre Verger

- Chico Mendes – image created by artificial intelligence

- Mãe Mirinha de Portão – image created from family archive

- Rio Doce – image created by artificial intelligence

- Pássaro Peito-Vermelho-Grande – image created by artificial intelligence

- Perereca-Verde-da-Fímbria – image created by artificial intelligence

- Gameleira Branca – photograph by Ayrson Heráclito

Materials: Bamboo, coconut fiber, mirrors, plants, gourds, pots, quartinhas, water jars, white fabrics (ojás), burnt oil, projection tulle.

Ilês, Aiyês, Carnavais e Ancestrais (2023)

- Voices: Tiganá Santana

- Percussion (Ilê Aiyê): Mestre Mário Pam (3 surdos, pandeiro, and conducting); Ru Paixão (caixa); Serginho Pam (repique and tamborim)

- Special Participation: BaianaSystem

- Recording: Sebastian Notini and BaianaSystem

- Mixing: Sebastian Notini

Perder a Imagem (2022)

- Conception and Execution: Tiganá Santana and Itaú Cultural

- Curatorship and Original Sound Work: Tiganá Santana

- Sound Design and Mixing: André Magalhães

- Recordings (BA / SP): Sebastian Notini, André Magalhães, and Juninho Costa (Junix)

- Musicians: Ldson Galter (bass), Sebastian Notini (percussion), Juninho Costa (Junix) (guitars), André Magalhães (percussion and effects), and Tiganá Santana (guitar and voices)

- Special Participation (voices): Juçara Marçal

- Exhibition Design: Anna Turra and Stella Tennenbaum

- Accessibility Project: Itaú Cultural

- Mediation Content: Formação Itaú Cultural