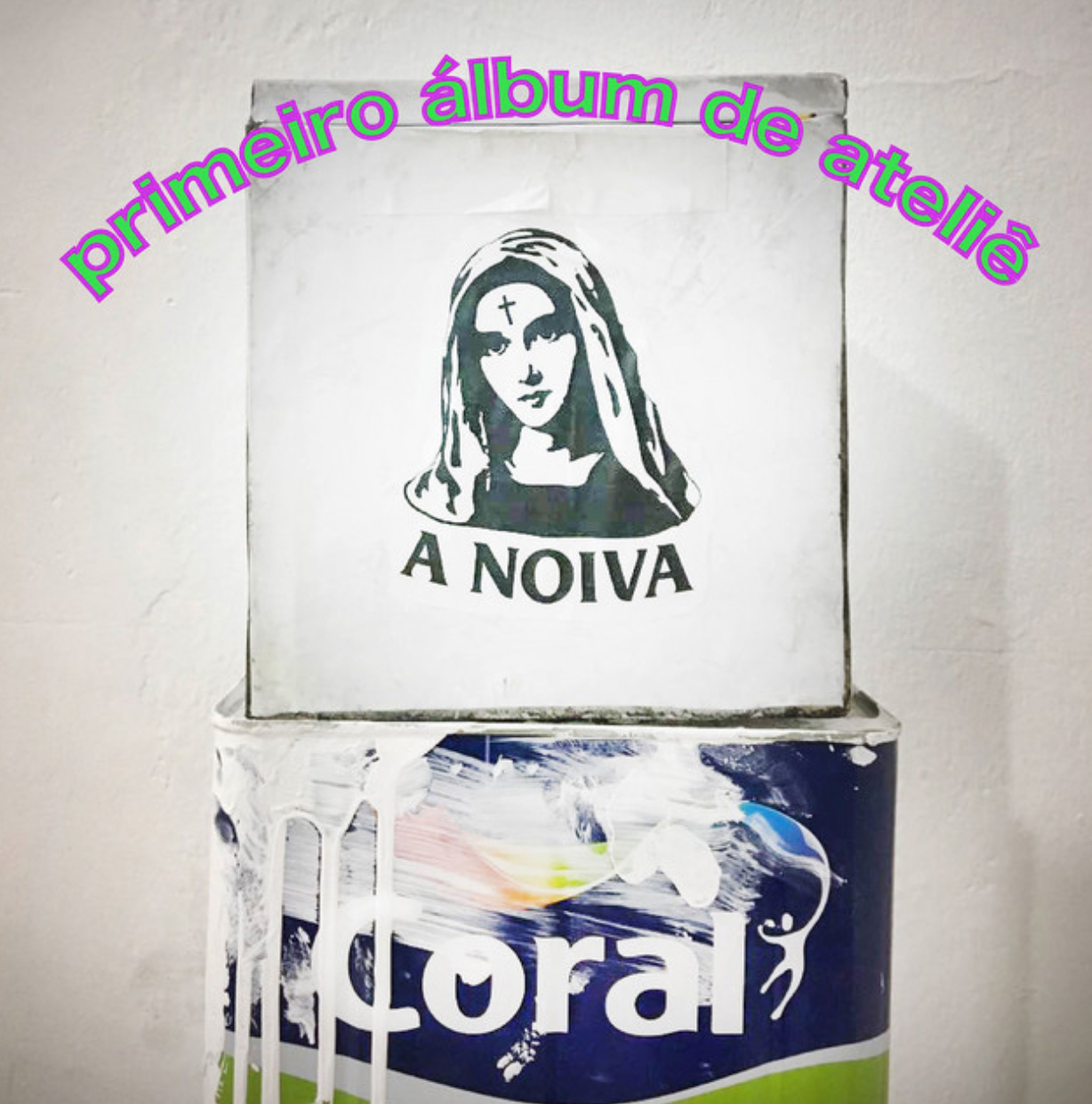

After gaining recognition for his iconic brown paper paintings, Maxwell found in music a natural extension of his creative practice. Since his days as a street rollerblader—when the sounds of the city guided his movements—music has held a central place in his life. A turning point came in 2017 with the founding of the Igreja do Reino da Arte [Church of the Kingdom of Art], known as A Noiva [The Bride], of which Maxwell is a founding member. It was within this context that he and fellow artists created Coral, the group’s first studio album. The result of a singular tithing system that required artworks instead of monetary offerings, the album captured voices, raw instrumentals, and samples that gave form to the movement’s shared imagination.

More than a musical release, Coral became a document of the artistic convergence within A Noiva, marking the beginning of a journey in which music would take on an increasingly central role in Maxwell’s practice and that of his peers. This seminal album laid the groundwork for a growing discography, now composed of four releases. Rio de Janeiro—cradle of the movement—echoes through the album’s sonic textures: in its references to the evangelical world so deeply rooted in the city’s outskirts, in the close relationship between faith and community, and in the rhythms that resound in samba circles and along the city’s shores. The vocal atmosphere of the album fuses prayer with irony, creating a sonic tapestry that is as intimate as it is irreverent.

The themes at the heart of Maxwell’s studio practice resonate throughout the album: paintings that resemble prayers; art-making as a sacred act; the invocation of historically charged colors such as Prussian blue; and a relentless pursuit of truth through the creative process. With a raw and experimental aesthetic, Coral layers unison voices, organic instrumentation, and samples that construct a universe at once earthly and spiritual. The songs abandon conventional structures in favor of a near-ritualistic flow, with the choir functioning as a unifying force. The voices do not aim for technical perfection, but for communion—evoking an intimate, profane liturgy driven by collective desires for affirmation, imagination, and belonging.

Maxwell reflects on this process: “When we created a Church for artists, I knew right away we needed hymns and songs of praise. You can’t conceive of a Church without a choir, without its musical dimension. One of the members of the Church is cosme sao Lucas, one of the few in the congregation whose primary language is music. I followed part of his creative process while he was working on his first album, Aprendendo Autotune. In 2019, he sent me a track layered with beats, melodies, and vocal textures I couldn’t quite place. It sounded strange at first—I’d never seen anything like that approach to composition. But when I received the final version with lyrics, I understood the essence of what he had made, and I felt an instant surge of excitement. That exchange brought me much closer to music, awakening in me a powerful desire to create.

Over time, I’ve also gathered backstage experiences across the music world—from live shows to studio sessions with artists like BK, Djonga, Baco Exu do Blues, and Filipe Ret. I saw BK and Baco create a track from scratch, right in front of me. One especially memorable moment was visiting Baco during his creative isolation at Toca do Bandido, where he was working on Bacanal—an album that was never released. I had the privilege of witnessing part of that truly remarkable process.

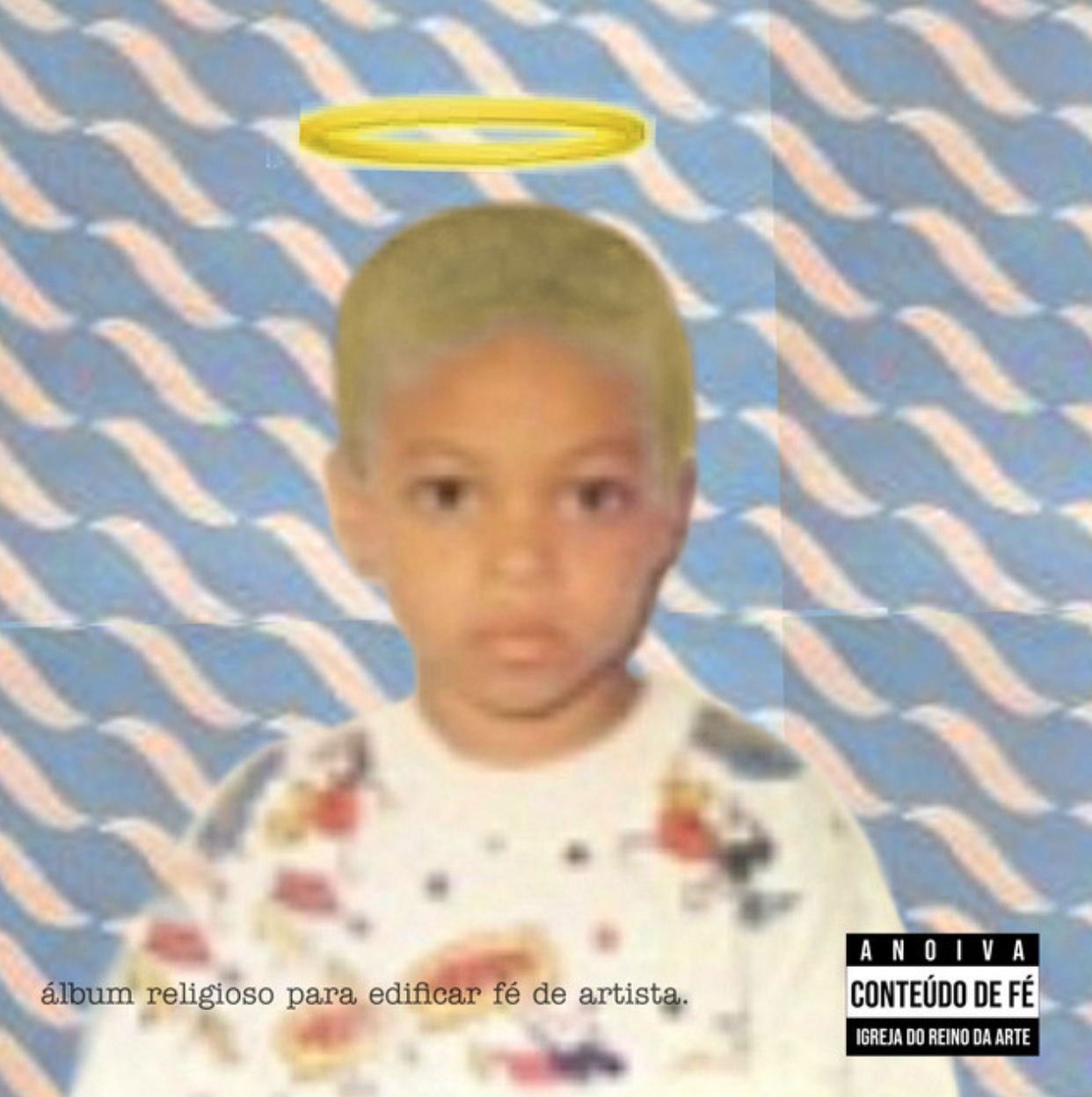

It is from this fertile ground that Anjo Maxwell [“Angel Maxwell”] emerges—the third album released by A Noiva and the artist’s first solo work. Here, music transcends the notion of detour, affirming itself as a natural extension of Maxwell’s expansive creative field. Each track functions like a page from a sonic diary, where he documents—through equal measures of rawness and lyricism—the challenges and triumphs of an artistic life: routines, exhaustion, euphoria, doubt, and an unshakable faith. What comes through is a clear urge for composition, for inhabiting music with the same intentionality that marks the construction of scenes and characters in his visual works.

The album navigates experimental and independent terrain, carrying the weight of someone acutely aware of the world around them. Minimalist beats support an unpretentious voice that exposes itself without embellishment, while the arrangements preserve the rough honesty of a sketch. These are songs that embrace their processual nature, unafraid of the vulnerability that defines them.

Maxwell recalls that the first track he ever created entirely on his own was Deus é Ciumento [“God is Jealous”], whose lyric “seems like arrogance but it’s shyness, my first track, my first time” encapsulates the spirit of that beginning. It was 2020, the year the pandemic swept across the globe, when he committed to creating a Tithe every April 1st. Within A Noiva, the Tithe is the artist’s personal offering to the entity known as Altíssima Arte [“The Most High Art”]. For that specific date, the proposition was to confront something completely outside his comfort zone—something he had not yet mastered. This willingness to dive into the unknown became a defining trait of the project’s genesis.

We see a tension between the expansive drive of Maxwell’s visual universe and the deliberate vulnerability assumed in his songs. Whereas his visual art constructs epic narratives of Black and white bodies, his music unfolds on an intimate scale, like someone making the first mark in a brand-new notebook. The isolation of the pandemic became a laboratory for this transition: the Tithe to Altíssima Arte, once about technical mastery, became an exercise in surrender. In this act of letting go, music reveals itself as another face of the same sacred process that animates his paintings. The minimalist arrangements and stripped-down voice do not indicate limitation, but rather signal a rite of passage: the artist dismantling his persona to find, in relinquishing control, a new way to inhabit the world.

The track Meu Santo Tolezano is an homage to his friend and collaborator Lucas Tolezano [cosme sao Lucas], a fundamental figure in multiple dimensions of Maxwell’s path. As mentioned earlier, it was with Lucas that Maxwell first learned to listen to music as a creator—a process that awakened in him the realization that he could generate his own sounds. Experiences shared with rap artists also helped expand his perception. Being present at rappers’ recording sessions allowed him to grasp a whole new, accessible creative universe. This relationship with music led Maxwell to create album covers for artists like BK. His exhibitions began to merge painting with sound performance—such as in the opening shows for Pardo é Papel [2019] at the Museum of Art of Rio, featuring performances by BK and Baco Exu do Blues. Years later, Bruno Berle would perform at the opening of Maxwell’s first pavilion [2023] in the São Cristóvão neighborhood.

Alexandre Maxwell, Sem título, from Novo Poder e Pardo é Papel series (2019).

Maxwell moves effortlessly among musicians like Dada Joãozinho, Joca, and cosme sao Lucas—artists from the Niterói scene who share expanded visions of language and a sharp sensitivity to the present moment. His auditory repertoire spans a wide range of references, from Chico Buarque, Caetano Veloso, and Jorge Ben Jor to Solange, Playboi Carti, Rosalía, and Filipe Ret.

The philosophies articulated by Maxwell weave together sharp critiques of the art market with celebrations of intuition in his creative processes, as well as odes to transgressive painters like Lucio Fontana. Self-affirmation, a crucial element in rap, often emerges as a voice of empowerment and bold assertion, making it even clearer how his paintings resonate like true rap lyrics. In a conversation with Tolezano, I heard that these are intimate confessions leading to a deeper understanding of the artist’s imagination—in anjo Maxwell, we are immersed in the sincere expressions he usually nurtures in silence. For any curator, it becomes essential not only to listen attentively to the album, but also to trace Maxwell’s steps through the art world.

“My barn, my seed: Rio de Janeiro,” declares a line from the song Capital da Arte Contemporânea [“Contemporary Art Capital”]. In it, Maxwell names Brazil’s former capital as the vibrant center of contemporary art, proposing a new perspective on the city’s cultural power. Rio de Janeiro—with all its glories and wounds—remains both source and stage. The city pulses through the verses and silences of anjo Maxwell, becoming mythological ground; a place of origin and a symbolic territory that he insists on naming as the “capital of contemporary art.” Far from ironic, it is, in fact, a sincere affirmation—an invitation to shift centers and redraw maps.

In exploring the history of Brazilian art, one finds in the reflections of art critic and curator Frederico Morais (1936) a statement that echoes Maxwell’s vision of Rio de Janeiro.

In 1966, on the occasion of the first exhibition he organized in the art world, “Vanguarda Brasileira” — featuring only artists from Rio de Janeiro and held at the UFMG rectorate — Morais wrote in the catalog-poster text: “Rio de Janeiro is a happening, a place conducive to creative freedom and where there is no commitment to traditions or to what comes from outside. That is why the artists I present have minds open to the ongoing pursuit of the new and the meaningful.”

According to curator Cristiana Tejo (1976), “this feeling of freedom grows as one recognizes Rio as an open city, built through the fragmentation of cultures and territories. Rooted in rhizomes of colors and Brazilian accents. Rio, perhaps the most Brazilian of all cities.”

And it may be precisely in this geography of multiplicities—where colors, sounds, and identities intertwine without asking permission—that an artist like Maxwell Alexandre finds his creative ground. After all, what does it mean to make music as a Black visual artist from the periphery, with international exhibitions in cities such as Paris and New York? For him, the answer seems to lie in the ongoing act of re-signification. His foray into music is not a leap into the unknown, but rather another gesture of expansion—as if understanding that creation cannot be confined to rigid categories. If his paintings on brown paper already carried their own rhythm, music now emerges as a new language to name the same astonishments and urgencies.

There is a quiet provocation here: how does one occupy consecrated spaces in the global art world without being shaped or contained by them? How does one keep their feet grounded in local realities while engaging with institutions that have historically excluded bodies like his? In this sense, music functions as a tool for displacement—a means of excavating memories and imagining possible futures, without asking for permission.

The sounds that echo in anjo Maxwell are not the same as those found in the European halls where his paintings are displayed. These are beats that carry the crackle of the streets, the cadence of hustle and flow. When an artist from the periphery chooses to make music rather than limit himself to painting, he’s asserting in the same breath: “I decide how many places my voice can inhabit.”

That may be the central point. In a world that insists on classifying, separating, and ranking artistic languages, Maxwell moves in the opposite direction, demonstrating how music, painting, and performance all flow from the same source. His trajectory confirms that art requires no passport—he crosses geographic and social borders with the same ease his work shifts between the sacred and the profane, the local and the global. He can exhibit in Madrid while keeping his traveling pavilion alive in Rio’s neighborhoods.

In this context, making music goes beyond being a mere extension of his practice—it becomes a political act of sonic occupation. It’s a reminder that the same bodies dancing at favela parties also walk through the world’s museums, and that no space is out of reach. Maxwell Alexandre is expanding our understanding of what constitutes a work of art. His second album, titled DaVinci, is currently in production and includes over forty new tracks, signaling a leap in creativity five years after his debut release.

Now even more internationally celebrated for his monumental paintings, the artist welcomed me one afternoon into his apartment in Aterro do Flamengo, where I was able to listen to early recordings of the new project. The intense sunlight of a bright day streamed through the wide windows. As we entered the office that also serves as his home studio, small oil pastel works could be seen hanging on the walls. His six-month-old daughter Goia played near the work table while his partner Raissa moved between rooms. Maxwell, calm and focused, shared his new creations. From the studio window, the imposing presence of Morro da Viúva framed the landscape.

In this domestic space with a privileged view of Sugarloaf Mountain, it becomes clear how social ascent, fatherhood, and family life have introduced new rhythms into his creative process. The artist who once operated in a constant state of creative frenzy now finds in the steadiness of home life the time he needs for both painting and composing. His restless mind, however, continues weaving connections and remains the core of an ever-evolving artistic network.

The new songs reveal a clear creative maturity. What once was search now becomes assertion. In lyrics written over the past year, Maxwell fully embraces his paradoxical position: a painter with the salary of a football star, who recognizes having “improved the scene” for artists in general while simultaneously poking fun at the art system. “Mercy, son, you have a spirit of greatness,” says one verse that encapsulates this ambivalence.

The album functions as a second intimate studio diary, recording everything from memories of carrying refrigerators through the alleys of Rocinha to the contradictions that come with success. Maxwell names his artistic parents—Cadu, Eduardo Berliner, Charles Watson—and claims his lineage in Matisse, Bacon, and Lucian Freud. He addresses thorny topics head-on, like not being paid by a European collector, the market pressure to determine the price per linear meter of his work, and the hypocrisy of traditionally racist institutions.

Sugarloaf Mountain, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

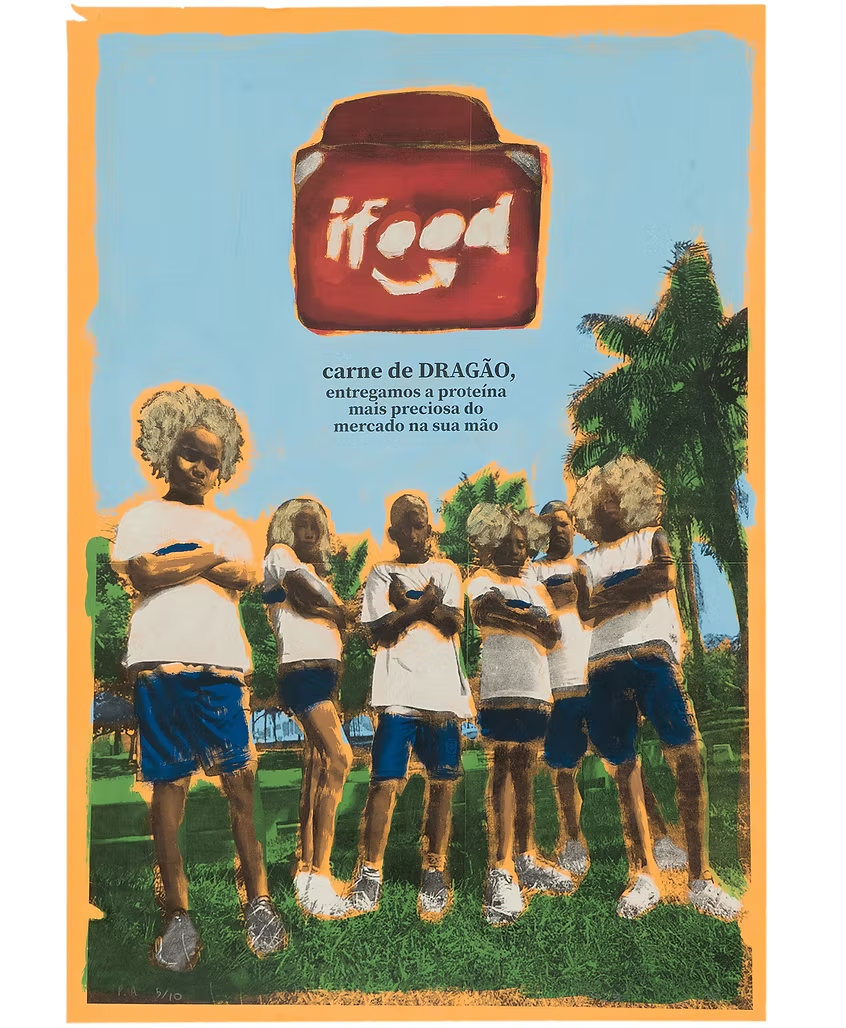

In its most revealing moments, the obsessive artist emerges—spending endless hours in pictorial investigation at the studio. Some tracks revisit mythological elements from his paintings, like the battle cry that echoed through the alleys of Rocinha during the procession-performance Carne de Dragão. Others invent fantastic origin stories for everyday products, like Danone, which has long populated his visual narratives. Fatherhood surfaces as a theme, adding layers of affection and reflection on identity. In contrast, his relationship with the police remains a shadow—a reminder that racism doesn’t end with financial success. Being a Black man on the rise in Brazil places Maxwell in a paradoxical position, where privilege and vulnerability coexist in constant tension. These themes are not explained, but lived—and they resonate like deep notes in a composition, present even when unnamed. In this album, as in all of his work, Maxwell constructs a complex portrait of the artist in the world, complete with contradictions, vanities, and unsettling truths.

The new compositions reveal clear artistic growth. His voice, now recorded with greater intentionality, gains in weight and presence. The samples forming the musical base show boldness in their references—not as gratuitous citations, but as conscious dialogues with the Brazilian musical tradition, expanding the scope of the work while maintaining its experimental essence. This technical and conceptual evolution transforms each track into a denser sonic territory where cultural heritage and innovation organically merge. The blend of traditional and regional sounds with international influences evokes a production aligned with MPB [Brazilian Popular Music], especially through its political and cultural themes and sophisticated poetic language. The use of piano and guitar, often repeated, brings a mantric structure that promotes a heightened state of attention. Altogether, the result is a rich and complex document that deeply reflects the musical identity of Brazil.

Speaking about the album’s creative process, Maxwell reflects: “There’s no fixed order between writing lyrics and creating the beats—it all alternates. I think I started by writing, since I didn’t know how to make beats. Then I began downloading instrumental tracks from the internet and trying to fit my lyrics into them. Only at the end of last year did I develop a method that gave shape to my process: I download songs using a specific program that musician Bruno Berle introduced me to, which allows me to separate all the instruments. I take one instrument into DaVinci—the video editing software—and listen, cutting out small fragments until I find a rapó. I write rapó because I like this Brazilianization of the French word rapport. In design, especially in fashion and print, it refers to a module that, when placed side by side, completes a pattern infinitely. That’s how I’ve been building my beats: each layer arises in its own moment, always like a mantra where a small piece of an instrument repeats and forms the music. I’ve been really enjoying the results—these are songs I’m proud of creating, and I can listen to them all day. The idea of mantra and repetition aligns with the religious dimension and with my daily, repetitive work ethic as an artist. When I find the rapó, I feel like my music improves. It’s like I’ve evolved musically—I can’t even explain it. The lyrics and flow have gained quality, and the songs started flowing more naturally and unpredictably. The melodies are unpredictable because the beats are, and the fact that I’m not technically trained in either voice or production results in something that feels authentic to me, even though my current goal isn’t exactly authenticity in music.”

In our conversation, I understand that the album is grounded in his experience as a male body—favelado, military, Christian, and artist. That’s precisely why the sound he creates becomes an essential key to understanding his conceptual narrative. With so many direct messages functioning as diss tracks—in the musical context, especially in rap, tracks that criticize or challenge other artists—it’s clear that there are territories where painting cannot reach, and music becomes the medium to accomplish specific goals.

If in his first album—anjo Maxwell, álbum religioso para edificar fé de artista—there was a sense of direction, as it was made for artists, in DaVinci, Maxwell moves toward a more idiosyncratic path. He affirms:

“This is an album I’m making for myself—to better understand everything I’ve been articulating in the mythology I’ve been developing, to understand myself better as an artist, to become more of an artist. I feel vulnerable working in a field I don’t dominate. I think making music is a way to create challenge and instability in my life—it can’t all be too good, too comfortable. I need to take risks again, risk losing it all, be embarrassed. I feel like the two activities complement each other, and I swear to God that I paint better now because I make music. At the end of the day, I sing to sharpen my drawing and vice versa. I draw to improve my rhythm, I paint to enhance my melody.”

He estimates it will take about another year to complete the album and seems well aware that this is, above all, a path of self-knowledge and creative expansion. For Maxwell, music transcends commercial circuits and becomes a space of experimentation where affections and tensions take form. His work does not aim to conform to industry formats or market expectations, but to overflow—through sound—what pulses in his creative universe. More than simply producing songs, he builds sonic art landscapes that carry the same urgency and density as his canvases, affirming that his artistic practice—no matter the medium—stems from a vital need for expression, artistic autonomy, and intuition, rather than a logic that transforms artistic productions into mere consumer goods.

And he explains: “I’ve always challenged myself from that energy music awakens in the body. Sports were a way to channel that energy. Now, as a maker, music becomes the thing in front of me—the thing to be appreciated, far less a tool. It takes on the quality of art in my life, in the sense of aesthetic contemplation.”

With a career spanning cultural production, arts, education, writing, and research, Nathalia Grilo’s paths revolve around Radical Black Imagination. She works as a narrative curator at the studio and pavilion of artist Maxwell Alexandre and is also a curator at HOA Gallery.

Additionally, she is part of the Levante Nacional Trovoa movement, writes about music, poetry, and visual arts for the Missa Negra column at Sobinfluência publishing. She leads the Negrume program on Rádio Veneno, sharing her studies on Black Spiritual Music. Nathalia curated the music section at the Virada Cultural de SP in 2022 and the Pulsar edital of SESC RJ in 2023. She conceptualized, produced, and curates the Ayó Encontro Negro de Tradição Oral and the Mulambo Jazzagrario Instrumental Festival.

Nathalia Grilo is a Black woman from the far south of Bahia, a migrating body, and a mother..

Maxwell Alexandre [b.1990, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil].

Guided by the concept of self-portrait, Maxwell Alexandre’s practice extends beyond the traditional categories and structures of art making. Through a logic of citation, appropriation, and association of images and symbols, as well as the use of materials of emblematic and biographical value, Alexandre builds a pictorial mythology that touches on religiosity and military themes. He similarly confronts the institutional status of contemporary art and the limits of aesthetic experience.

Raised in an evangelical household, Alexandre competed as a professional skater and fulfilled military service, knowledge that fundamentally sustains his output. In 2018, the artist received the São Sebastião de Cultura Award from the Cultural Association of the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro, in the category of Plastic Arts. That same year, Alexandre participated in an artistic residency at the Delfina Foundation in London. In 2020, the artist won the prestigious PIPA Prize and participated in an artistic residency at the Al Maaden Museum of Contemporary African Art, in Marrakech, Morocco, resulting in an installation for the group exhibition HAVE YOU SEEN A HORIZON LATELY at the same institution.

The following year, Alexandre was named artist of the year by the Deutsche Bank and listed as one of the top 35 avant-garde artists by Artsy. In 2023, he was awarded “Man of the year” in the Culture category by GQ magazine. Also in 2023, the first Pavilhão Maxwell Alexandre was inaugurated in São Cristóvão, followed by the second Pavilhão in the favela of Rocinha, both in Rio de Janeiro. From March to June of the subsequent year, the Pavilhão Maxwell Alexandre 3 was held at the Museu Histórico da Cidade, Rio de Janeiro, featuring the series Clube.

Alexandre has held solo exhibitions in Brazilian and international institutions and galleries, such as Sesc Avenida Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil (2024), for which the artist received the São Paulo Art Critics’ Association (APCA) award for Best National Exhibition; Casa SP–Arte, São Paulo, Brazil (2023); Cahiers d’Art, Paris, France (2023); La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain (2023); and Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France (2021). His solo show Pardo é Papel was followed at The Shed, New York, USA (2022), Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, and the Fundação Iberê Camargo, Porto Alegre, Brazil (2021), the David Zwirner Gallery, London, UK (2020), the Museu de Arte do Rio – MAR, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and the Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, France (2019).

His work is included in the collections of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Brazil; MASP, Brazil; MAM Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Museu de Arte do Rio – MAR, Brazil; Museo Nacional Centro de Reina Sofia, Spain; Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, France; Pérez Art Museum Miami, USA; Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, UAE; and Zabludowicz Collection, London, UK.

To know more about Maxwell: @maxwell__alexandre