Andrew Frederick: Okay, let’s just go for it!

Max Dowd: Would you tell me a little bit about how you came to start Croft and what your background is?

AF: Sure! I went to school for Architecture, but was also working as a carpenter to pay my way through college. So I always had one foot in the office and one foot in the field and I liked it that way. I always felt a little too hemmed in when I spent too much time in the studio, but it’s also a bit of a coarse-grained life to just be doing carpentry all the time. It feels like there’s a lot that gets ignored in the gap between the two, and there’s obviously, as you probably encountered, this kind of obstinance between Architects and builders that just exists in the industry. It is weird to walk the tightrope between those things. I guess I first dipped my toes into prefabricated (building) when I was working with another design build firm, in 2013, and they wanted to start doing prefab and didn’t really know how to do it; they didn’t have anyone on their team who was well versed in it, and I just happened to be the individual that had enough experience in both areas, so they told me to just go figure it out.

MD: But that wasn’t straw based insulation panels like you do now with your own company, Croft, right?

AF: No…At the time they were big foam SIPs (Structurally Insulated Panels). I have always had a knee jerk reaction against utilizing synthetic materials. Growing up here in Maine where I really witnessed firsthand what happens in the course of environmental degradation, I have always had this gut instinct around using healthy materials. So back then, using what little knowledge I had– and trying to convince a builder who was staunchly stuck in their ways using these foam based insulated panels – I managed to sort of backpedal with them, and since I was setting up the prefab shop, I got to establish what kind of wall section we were going to use. I designed a different wall that utilized cellulose and Rockwool and a bunch of otherwise conventional materials, but it was transformative. You could see immediately how much easier it is– to frame an entire building, install all the windows, make everything weathertight, like giant Legos, all at waist height without lifting heavy objects – in a shop environment. I think the first project we did, we saved 10% of the budget switching over to prefab. And that was during the learning curve, right? That was before we really realized any efficiencies.

MD: And those cost savings come in the form of labor and transport?

AF: It’s really just labor. I mean, you’re utilizing the same materials. In fact, in some cases, you’re using more because you have to prepare these things for the stresses of being lifted up by a crane and moved around on trucks. And there can actually be a penalty for both transport and additional materials, but your labor costs are so much lower. Just think about the movement of a single sheet of plywood that needs to be installed on a second floor. Typically, you’re going to have 2 or 3 people working in tandem, lifting this single thing up on several ladders of staging in order to get it up to the height that it needs to be at. Then they’re fighting gravity and carefully holding it in place while they nail it. It’s just cumbersome and a little bit ridiculous, especially when really looking in at the Swedish process for prefabricated buildings.

MD: The Scandinavians are really on top of that stuff – they’re incredible. So how did you go from working for a company and figuring things out on someone else’s dime to being like, screw it, I’m going to do this myself?

AF: It was at a conference for high performance buildings in late 2019, and one of the speakers there presented this information about this Canadian, Chris Magwood, who runs the Endeavor Center, who had just finished a thesis on so-called embodied carbon, which is the environmental impact of extracting raw materials from the environment; processing them, manufacturing them and delivering them ready to market and then disposing them at the end of their useful life. And in this one slide there were statistics of all of these super efficient, high performance buildings that we’ve been making, paired with irrefutable evidence that it turns out to be worse for the climate to be making these high performance buildings with materials like foam than it does to just make a plain code compliant single family home with moderate materials like cellulose. That information revealed what you could do with plant based materials, particularly straw – which has a whole bunch of reasons why it’s great, particularly because we get to piggyback on the production of food. Think about it: we’re already growing these plants so we can eat the grain, which represents the top 2 or 3 inches of the plant, but we’re left with one to four feet of bulk material that really doesn’t get used for anything. And that’s nature’s carbon capture right there.

Croft’s straw walls, Maine. Courtesy of Croft.

MD: Amazing. So where does that grain come from? Is there local production in Maine for that?

AF: Yeah. I mean, I don’t know how many lessons we want to take from the era of colonialism, but Maine was the breadbasket for the original colonies in the US. And grains do very well here. With hearty winter varieties, wheat is very happy in our climate zone. So I started talking to all of these various farmers… To backtrack a little bit though, in some ways we first had to address the perception of things like straw bale construction. I heard the term straw bale construction and I thought of moldy hobbit houses. Like, that is what the hippies do and they always crumble and fail, and they’re gross. Why would you want that? But it turns out to be this incredibly durable material. It will last longer, through more intense moisture cycling, than the wood framing we’re using in every virtually building that we make. So, sort of in a state of disbelief, I went home and just for the heck of it built a panel on my porch, dragged it out into my driveway and tried to set it on fire. Then left it out for months and lo and behold, it was fine.

MD: I hadn’t realized the timeline on all this was quite so recent. I think I started following you around some of these early tests that you had and were posting – maybe not that one. But it’s been really amazing to watch your process.

AF: I didn’t realize it either! Actually I’d been stating the year wrong for up until about a month ago. I thought I really started in 2019 and then things got rolling in like January of 2020, but it was a year later. Fog of war. In fact, it was January of 2021 that I signed the lease in this unheated unplumbed warehouse on the waterfront in Rockland, Maine. There was a sparking 100 amp electrical panel and it was not fit for industrial production in any way, shape or form and I had a part time helper, who is amazing but could only ever work 10 -12 hours a week. I found this warehouse at almost exactly the same time that some clients, who I had worked with doing some building science consulting work, happened to need a home built. And I told them I would do it, but only if I could build it with compressed straw panels. And they said yes. And then I had to go figure out how to make compressed straw panels [laughs] .

MD: I love that ultimatum: you can have it, but this is the way I am going to do it.

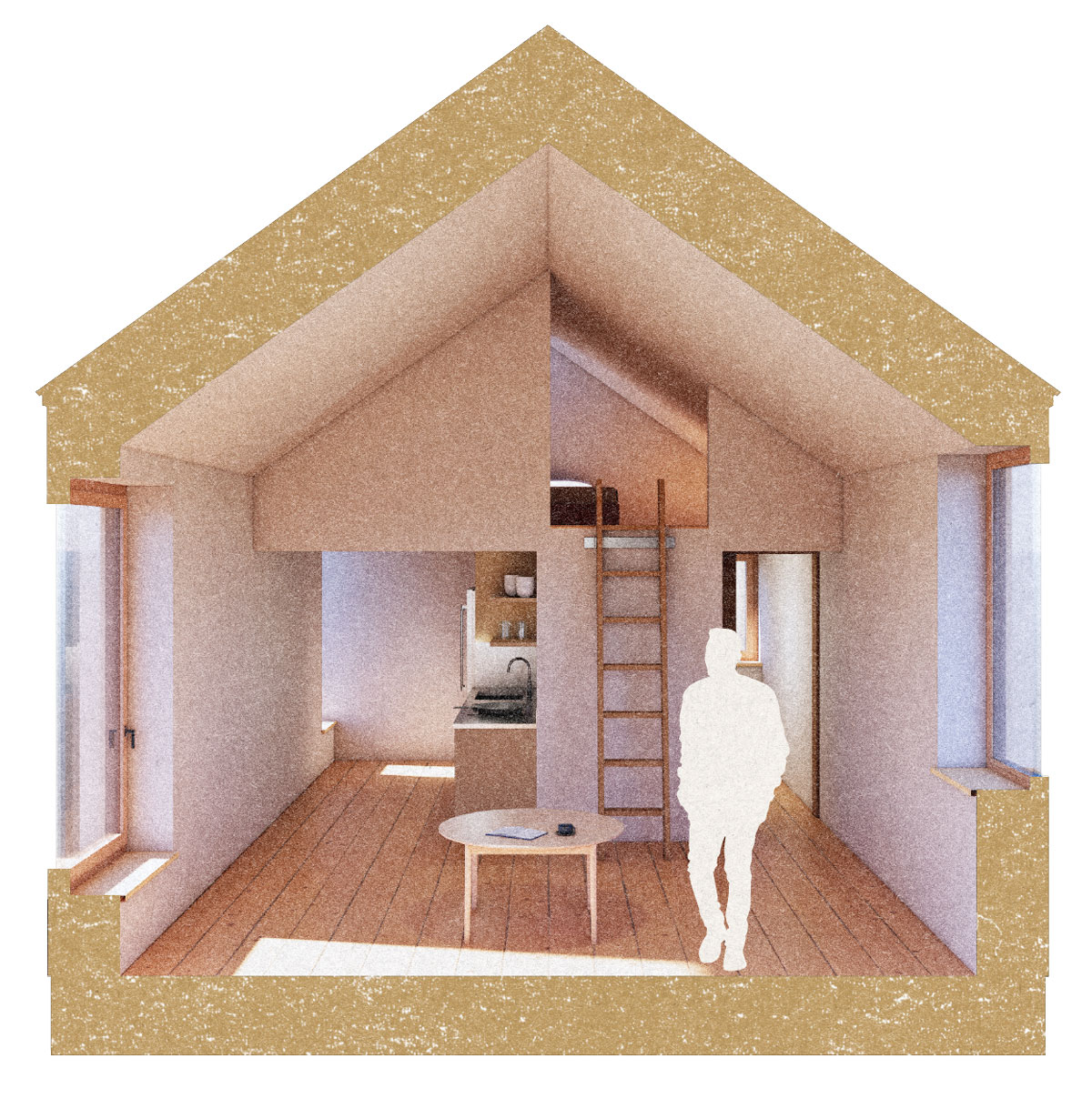

Section renders of existing Croft Kits, their in-house predesigned prefab building templates. Courtesy of Croft.

AF: Yes, it was truly unhinged. So I moved into that space in January and signed the contract on April 4th to make a house with compressed straw panels, having no contacts with farmers, no idea of how to actually make a panel like that, anything. And in the ensuing 19 weeks, I finished the design for the house with the client. It was really a client driven design, but he was not an architect, so he needed some hand-holding to make it structural. We poured the foundation and we built all of the panels for the house concurrent with building the machine that made the panels and patenting that machine, and then landed that house on its foundation in only five days of crane work in August.

MD: Even on the first attempt? That is a testament to the system itself.

AF: Yeah, just use simple systems!

MD: So there must have been quite a few mechanical failures of that compressing machine and craning process, I presume?

AF: Oh, God. The last count I had was over 250 iterations*.

MD: Using hydraulics?

AF: Correct. The latest uses hydraulics. The next version, which is being built right now, goes back to a tension based system. There is an elegance and an efficiency and, honestly, an economy to utilizing tension to do anything as opposed to compression, because with tension you’re just pulling things into the frame that already exists. You’re just tugging things, squishing things that way. Whereas with compression, you have to build an external armature to resist the outward thrust that you’re creating by compressing something inside.

MD: So some sort of cable that goes through the Straw panel to compress it ?

AF: Yeah, in basic function, it’s essentially like a giant loom that stitches the panel together. But designed by an idiot.

MD: That’s incredible. So now that you are where you are, could you tell us a little bit about how a typical project goes for you? Your website is very polished these days. There’s a product (predesign croft volumes) that people can click and buy, effectively. What happens when they say, yep, we want this?

AF: They never say that [laughs].

MD: Okay [laughs].

AF: No one ever just takes it off the shelf. Ever. I sort of knew that, going into this, and, honestly, it is such an appealing concept and hey – it’s appealing to me as a human being to have this readymade thing. I mean, you look at companies that not only have a marketing department, but they have a team of psychologists figuring out how to propagate their market share, and they’ve figured out how appealing their “buy it now” button is. And, okay, there’s psychology there at play that is icky, for sure. But that is just not really the way the construction industry operates. Often, if we’re not working with another Architect or another developer, we’re working with a homeowner and you’re building their home, right? This is something that is incredibly special and personal to them. So there’s always this sort of protracted design phase. And it is interesting to me that we kind of took this radical stance on materials, as a company, as an entity. But the design language that developed concurrent with that is, in a lot of ways, rooted in my very personal, pragmatic outlook on how things should be built, particularly in our climate.

There are decisions that are rooted in constructibility, speed and economy that sort of lend a certain aesthetic, I guess, to our buildings – if you want to call it that. But often it’s this design language that people respond to, in lieu of the mission-based stuff. So we just end up with this split where half of our clients are showing up and saying: we care deeply about climate action and the environment and we want you to build this because you’re dedicated to those things. And the other half is just not interested at all in the environmental angle. They’re just like: ‘that’s a cool house and we want that’. So – sure – it’s always different. There’s also a frustratingly diverse patchwork of rules and regulations constructing things in the US. When you add this all up, there really isn’t much of a common path between projects.

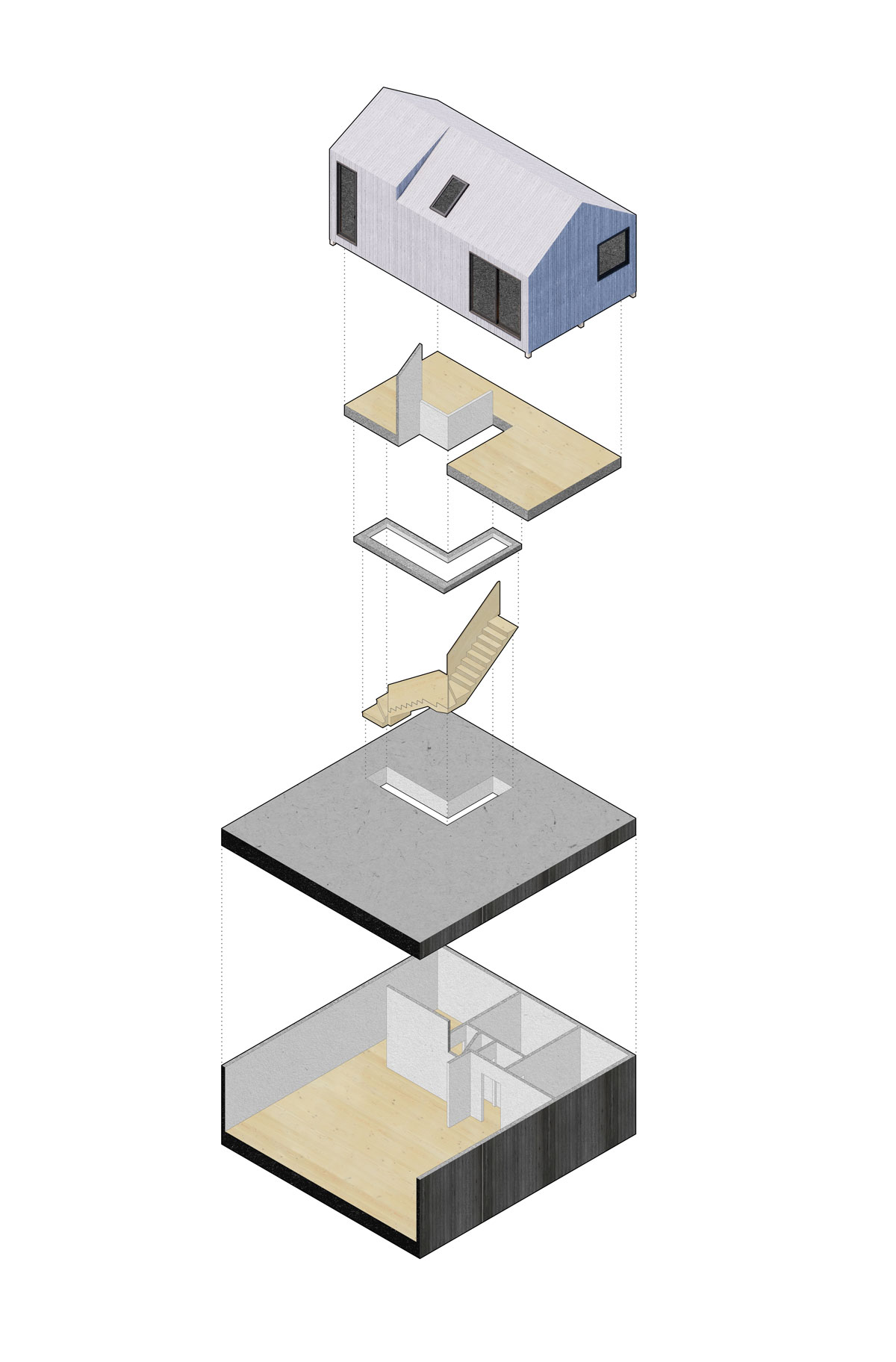

Exploded isometric for rooftop “perch”- extension/addition to existing urban building in Portland, Maine. Courtesy of Croft.

MD: What role do you think beauty plays in the conversation? Your houses are inherently beautiful, there’s a simplicity to them and the wall thicknesses are massive . How much time do you spend on that aspect?

AF: It feels like… less than I should? Like any human being, I’m the product of my upbringing, right? And to be raised in the United States prevailing culture of toxic masculinity, the conversation around aesthetics… I have increasing comfort with it, but historically I have felt a little squeamish trying to convince people in terms of beauty and aesthetics alone. I can talk about the performance of the building or the durability or the healthy materials that it’s made out of and make a compelling case as a dude [laughs].

MD: I can certainly relate to that uncomfortability with talking about aesthetic merits, unlike the building’s performance where inherently there’s a right and wrong, a measurable value..

AF: Yes. And it feels harder to sell people on concepts of beauty, but I see it in action. In early years I was using my own house as the ‘show home’ for potential clients to come visit. And to watch every single person move through that space and have the exact same response… it was as if you had scripted a movie for them…

MD: What were they saying?

AF: Every single one of them steps through the door, their eyes are drawn upward and they elicit this deep, loving sigh. And then as they’re walking through the space, (which at the time was 750ft² – I finally finished the other part of the house, which brings us up to around like 1040ft² now…) but people walk through the house with me and say, “this is amazing. What is this, 1500, 2000ft²?” And they say this without realizing that the circulation path has brought us about seven feet from where we began our journey, but it felt really long because of the way I had very intentionally sculpted that experience. So– I know that it works. I’ve witnessed it firsthand in a lot of our buildings, and I would love to emphasize it more in the work going forward, because it’s not just the materials we’re using. It’s the interrelationship of when you move from a space of compression to a space of expanse, when the air is literally draping over your body in a different way. When it sounds different. As a designer, this is not even figurative– you are literally tuning the resonance of this experience for people. I spend a lot of time thinking about those things, particularly resonance, and just… don’t ever talk about it.

MD: It’s a feeling. My partner and I just got back from our first trip to Japan and we were constantly talking about this feeling…. Similar to you, considering toxic masculinity and having a comfortability with more technical language and rights and wrongs, we’re not really equipped with the language to describe what that feeling is. But the feeling of being around natural materials, the textures, the acoustics, the humidity of the air…. they combine into this indescribable feeling. It’s a sort of peaceful feeling that I feel increasingly in tune with, but that I find really difficult to communicate. And you can’t communicate that in an image, it’s a multi-sensorial experience that only someone who stood in your building can feel. And it’s increasingly difficult to communicate that complexity with this very image based society that we live in. You know, the sexy instagram space that is likely built from crap, but it looks great, the light’s coming through the window and they’ve got the sconce from the sexy designer de jour.…

AF: It is such a bodily-experience thing. There are plenty of studies talking about the beneficial impact on mood of negative ions surrounding you – which are what natural materials are emitting– versus positive ions, which are emitted by synthetics.

MD: And we’re back to measurable things [laughs]. You know, I have this frustration with how siloed and removed the Architecture profession has become, with a contractor that cares about the bottom line, minimizing labor and material costs, and the Architect who is concerned with how the corner resolves itself, traditionally speaking. And you collapsing the two into a single process just makes so much sense. It seems to be the way forward for the Architects to become deeply intimate with the means of production…you have a much more efficient decision process and a higher quality outcome. You get to an early stage, cling on to the things that are meaningful to you. In theory, that sounds great, right? But what have been the hurdles structurally in getting there? It all seems very simple, but there’s a huge amount of financial and bureaucratic barriers to do both of those things. And the specialization required in both of those industries is wild.

AF: I mean, you hit the nail on the head. By sort of absorbing both design and construction into one entity, we really just get the joy of doing the big, important design moves that are so critical, where you’re establishing scale, space, light, circulation, siting, and then; all of the other stuff? Hey…you can put the worst countertops imaginable in that space and it won’t matter. It will still be a great space. So, you’re right, we at Croft kind of created the perfect candy store for ourselves, and I am eternally grateful that it has worked out as well as it has. But I think this particular entity grew out of the set of conditions that are available in Maine, and not necessarily available in lots of places. We have run into more hurdles going across state borders than we have ever encountered – even within the most restrictive jurisdictions – in the state of Maine. And certainly it’s not that the regulations are more relaxed. It just feels like–culturally– we are starting with the assumption of good faith on behalf of both parties; the code enforcement and the builder. That is turned on its head in most other places.

MD: You just have a better understanding of them.

AF: I guess so, yeah! I think there’s a level of polish [laughs] that would be expected if you were trying to put up a building in Manhattan. If we submitted our very simple plans and drawings to the city council or planning board, even in Boston, to put up one of our buildings, I think they would be like, who are these amateurs? What are you doing here? Get out of the room. But you do it in rural Maine or even the more sort of “urban parts” of Maine and no one bats an eye. Welcome to the club! Like, they’re just happy to see you putting up more housing.

MD: This is no news to you, but we live in this global marketplace of building materials. Especially in Manhattan, you just see glazing systems coming from Germany, cladding from China, cement from India, and often labor from Mexico. Croft is seemingly really swimming against this tide, using a local ecosystem of both materials and labor, which comes at a cost, right? How do you convince clients to spend that little bit extra to contribute to that ecosystem in a way that’s kinder to the planet and is progressive? Or is it that they’ve already made that decision and they’ve come to you because they already know that’s what they want and believe in. Are you having to wrestle that? Presumably a stick built house is maybe 20% cheaper, at least off plan.

AF: That’s a good question. I don’t want to ignore the fact that by the time they get to us, a lot of people have self-selected in. So there is certainly that aspect going on. Thankfully I’m not doing this anymore, but a contributing factor to this getting off the ground is that I’m actually, truly willing to starve for my ideals, which as a business owner – even if you’re willing to forgo all markup in an attempt to just establish yourself – you can’t do that forever. So you have a point. But I had the luxury of being able to do it on the first couple of projects and I made some tactical decisions about how to take deposits and how to attentively budget projects which turned out to be lucky and prescient at the time. But I actually feel the real win arrives when any person working with biomaterials and climate friendly buildings doesn’t actually have to argue for it specifically on its own merits anymore. That is one of the reasons that I am integrating prefab, and sort of wringing every ounce of efficiency I can out of every system we use. We’re buying our lumber and our structural sheathing direct from sawmills, so we’re paying almost a third of what we would pay if we went off the shelf. And we’d be paying that much more for terrible materials! Our natively grown rough sawn pine, for example, which is vapor open and has a whole bunch of other characteristics that make it a superior material, is cheaper per square foot than shitty mass-produced plywood or OSB. These things aren’t secrets, you just have to be willing to plan ahead.

Custom eave window on a Croft XS boathouse. Courtesy of Croft.

MD: So you’re not doing any plywood sheathing, you’re doing all board sheathing?

AF: Yeah.

MD: Wow. And all board sheathing is more labor?

AF: It’s more labor. But when you’re working on a framing table at waist height, you’re not holding anything up in terms of material flow. There’s a great phrase in carpentry about when you encounter a flashing detail, or when you’re up on a rooftop trying to figure out how to get the roofing to work around a chimney: Think like raindrops. You just think: how is future water going to want to move? Most buildings are – astonishingly – not very watertight, they’re just very good at negotiating with water, sort of encouraging it onto a certain path. There are a lot of lessons in that way of thinking when it comes to prefab, where we have a legacy industry which is mostly built around big, strong, (usually) men doing heavy lifting and sort of grunt work. And I’ve been steeped in that for decades, and trying to rebuild neural pathways around how to get this work done. So..this is going to sound trite and slightly offensive, but I’m constantly trying to think like a weakling. Like…how can I just do as little as possible to this material and to this workflow to end up with the finished product that I want? And, surprisingly, it’s not automation, it’s not utilizing more technology. Oftentimes it’s like putting a roller on one rack so that it’s easier to draw the boards off of one rack. It’s very, very simple solutions like that. In some cases, it’s just rethinking the final product altogether. That’s fair game too!

MD: It reminds of a talk of yours I was listening to once that you mention equating manpower to oil barrels, kilojoules of energy, and thinking of labor in that kind of direct way.

AF: Yeah. We’re still on that. There’s 11.5 years, 23,000 labor hours, in terms of the caloric equivalent of energy in a single barrel of oil. And we’re burning on average, something like 96 million barrels per day, just exajoules of energy (a very large unit of energy measurement, equal to 10^18 joules, used to describe massive amounts of energy consumption, typically on a national or global scale), everyday globally, not recognizing that if we were to follow that thread in terms of what we as humans are benefiting from; it’s as if we had human beings working for us for 3/1000ths of $0.01 per hour for their labor wages. We’re getting THAT value out of fossil fuels. It’s an astonishing energy source. I actually don’t think fossil fuels are the problem, I think these expectations and our cultural norms are the issue that we need to radically transform. We try to be an example of that at Croft, where we’re trying to not throw oil at a problem. People talk about throwing money at a problem, but no one really notices that in this transition to – whether it’s biomaterials in the construction space, or whether it’s green energy supply – the Achilles heel of all of that is the continued use of fossil fuels in order to access and accomplish these things. And this is a human problem, not a carbon problem or a fossil fuel problem.

MD: Given the sort of brain that you have and your sensibility and education, I could imagine that there’s also a temptation to try to eliminate fossil fuels from everything but we have to acknowledge the idea of perfection being the enemy of progress. I think Architecture can run away with this idealism that often thwarts anything getting done. I kind of suffer from it myself. If I can’t do it in a perfectly wrapped eco system where everything is connected, then I’m not going to do it, you know? Whereas it takes a real focus to solve things bit by bit and then get to those issues when you get to them.

AF: Yeah, you’re right. In particular, the amount of diesel that is burned in the last 5% of our work to power the tractor trailers that are delivering the panel trailers to site, the cranes… It drives me insane. But it is an iota off the amount of carbon that’s getting emitted and waste that is being generated by traditional construction methods. You’re right about the pursuit of progress. But even then… If you think about it, we haven’t even been doing the “less than perfect” thing for the past 300 years, we’ve been doing almost the worst possible thing. And I just wonder, what kind of transformation would we see if we were all thinking the way you just indicated? Like, “what is the best possible thing I can do right now?” Maybe not the perfect thing, but the best possible execution of this problem…Just imagine!

MD: In a way, that’s a truly sustainable business in the social as well as environmental sense . One where the economics work for you personally, that the time and risks taken doesn’t screw you and your family to the point where you’re ruined, maybe you over extend, get sued and the enterprise ceases to exist.

AF: Yeah, sure, that’s icing on the cake when it works out. There is a wave that has been established by other people, who-let’s be honest– are smarter and have been historically more dedicated to this than I am, as applies this concept of bio based materials, and more efficient buildings, and higher performing buildings without nasty synthetic foams. That wave is already here– Croft just sort of caught that wave in a lot of ways. But I don’t want to dismiss the fact that launching something like this also takes a willingness to flat-out refuse opportunities and rudely say no to other human beings and to just be very, very stubborn in ways that could potentially hurt you. I’ve said this before, but I feel the only reason I am running Croft is because it’s just very, very, very slightly easier than blowing up offshore oil platforms [laughs]. It’s just a little bit easier than eco terrorism, so I’m running Croft instead.

MD: You can do that on the weekends [laughs].

AF: It’s true. Everybody needs a hobby [laughs].

Croft’s Earth-Friendly Panelized Prefab. Courtesy of Croft.

Croft Kit S as a custom greenhouse. Courtesy of Croft.

MD: You’re on the ground, you’re in the trenches, you’re running the factory and you’re on site, presumably. But then there’s this other level of what you do that is getting involved in talks, symposiums, policy stuff. I’m still quite angry at my Architectural education and part of me thinks I should go back and do a seminar on natural materials or something. But then you’re not doing the thing and it becomes siloed in the other way where you have these academics at MIT, or wherever, that are just completely in the graphs but are not figuring out the logistics and the hurdles involved in construction. So I’m just wondering how much of that you’re trying to get involved in. You know, your time is precious. Are you getting involved in policy stuff or in schools?

AF: To a certain extent, yes. There are romanticized notions that I think all of us in the design world value. Material Cultures, in the UK, is a really good example of a group that is just so deeply embedded in the joy of experimentation and development and research, and it is a real luxury to be able to do that and hold that space and not have to deliver the project at the end of it! Material Cultures and MASS Design Group, and there is now the Northeast Biomaterials Coalition… I’m glad there are a lot of people who are trying to hold that space for education and policy work. And we are involved to a certain extent in policy work. But I feel the bigger challenge, as you just pointed out, is not identifying the problems and it’s not learning about the materials, it’s delivering the projects. Executing on the real-world logistics, in real time, with real consequences, is so much harder to do than it is to dream about even better potential solutions. And that’s where I feel deep frustration and impatience with the architectural field at large and with policy development. Basically, if with Croft I can get out there and prove that this is faster and easier and higher performance and then… sure, yeah, better for the environment… But just ignore that part entirely, if it’s just better and faster and cheaper, then you don’t need to argue any of the other points. All of the radical right wing climate deniers would just fall in line to buy your product because it’s now meeting their needs And that’s where policy can help for sure. As we just discussed, oil essentially is subsidized to the nth degree in a way that is almost impossible to compete with, but somehow we’re out here doing it still. And we have a willing list of people waiting for these buildings.

MD: So how many projects are on the waiting list right now?

AF: Oh, my gosh. I don’t actually know, because it’s not my job to know anymore. I think the wave that had been generated by other people just sort of prepared us for this moment and I don’t want to ignore that. But I don’t know if we are able to keep track anymore.

MD: That’s amazing!

Part of Croft’s Architect packet for guidance. Courtesy of Croft.

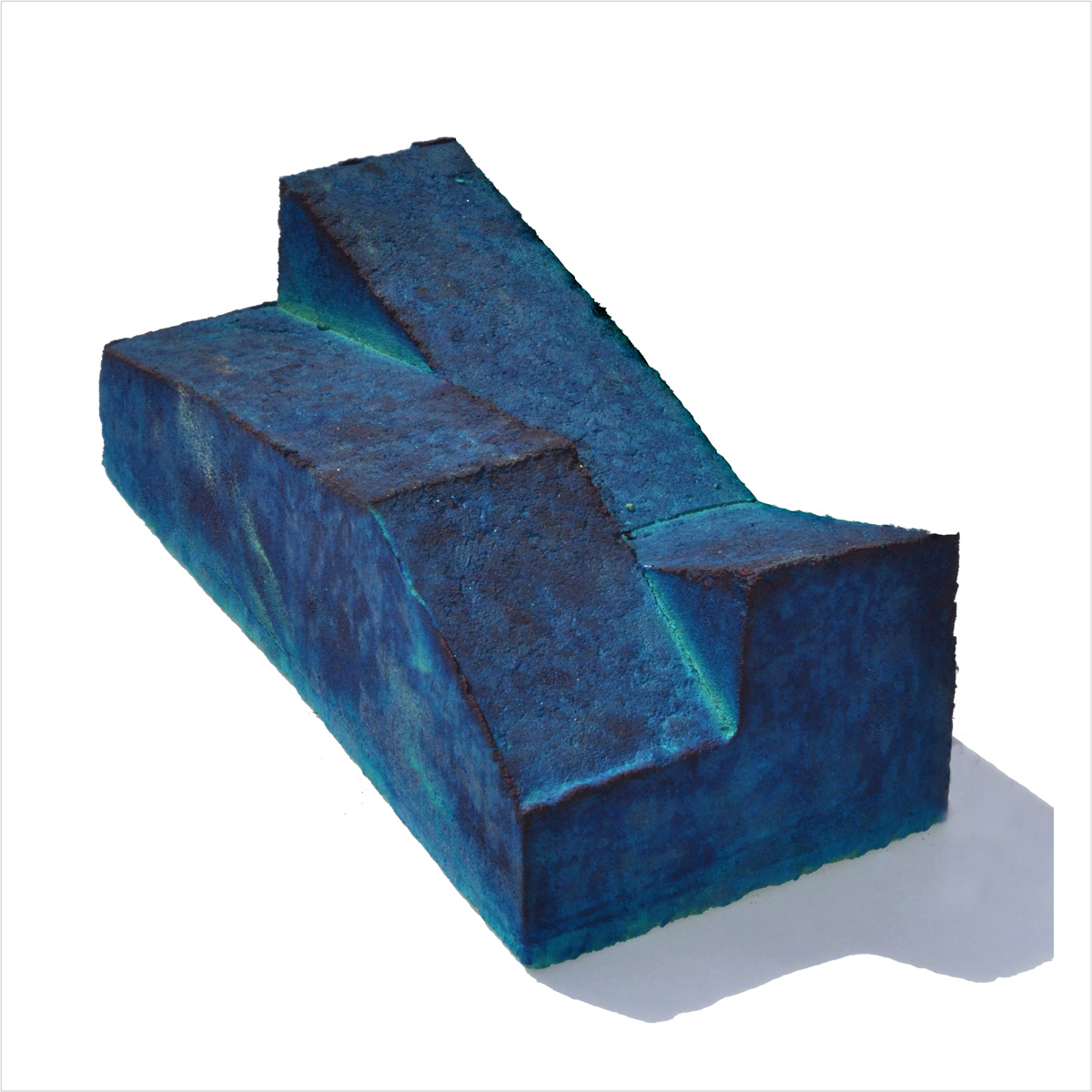

AF: Now, I actually want to talk about some of the work that you have done as well. There’s a compressed rammed earth block you made that I think about on a daily basis. I want to build something with that blue brick. It’s so cool.

MD: Oh yeah? Ah, me too. Yes the compressed earth block came out of my Thesis Project at the Cooper union looking into Low carbon alternatives to Housing in East Africa where imported materials and labor from China are driving the construction boom but with none of the associated local economical benefit. After leaving Cooper, I then worked at Grimshaw Architects and after years of drudgery there, I was put on this project in Bangladesh. They had this pro bono arm and because of my experience with MASS Design Group, they sent me over there and I actually took the brick machine with me. I put it in my suitcase thinking: these guys will need it more than I need this thing in Brooklyn, you know? Now, I kind of wish I didn’t (laughs) because I have more time working for myself now and I want to get back into that kind of experimentation right here in New York. My thinking has shifted into believing that we really need that kind of research right here, in the so-called “modern Rome” where we are so far behind on Ecological Material practice. But, I’m sure you’re aware, there’s a lot of failures in experimenting. Which is really disheartening, especially in New York, where every failure costs you 1500 bucks. It’s the time and the materials and the hiring of the U-Haul. And it sometimes feels lonely. I often look to those European organizations like Material Cultures, BC Architects or Assemble, who seemingly have this space and institutional support to make mistakes on someone else’s dime rather than it being a very personal, seemingly ludicrous and eccentric endeavor.

AF: This is the US [laughs].

MD: The Healthy Materials Lab is great and it’s been nice to see them fly the flag a little bit, but it doesn’t seem like they have a practical laboratory aspect to it, which I’d love to see in some of the New York institutions. Practical stuff like getting the students to build up wall sections and get messy with their hands and get off the computer and get that embodied understanding of the materials and the waste streams as well.

Max Dowd’s Earth Bricks – Low cost Housing Kigali, 2016-2020. Courtesy of the Architect.

AF: Yeah. And it feels to me there’s this idea that the learning happens in one place, and then the work, the actual construction of things, happens in another place. And programs like Rural Studio have been solving this. But when you intimately know how terrible most new construction is, but then you see Architectural jewelry being created by Architecture students with the highest possible craft and structural integrity? It just feels like, can we please just have them build the homeless shelter, a lasting, meaningful contribution, instead of a pavilion that is going to get torn down in two weeks?

MD: What are the main barriers that you’re facing currently? And what do you hope for in the next 2 or 3 years?

AF: I think I’m just coming up for air in terms of having been just so deep in it – establishing systems and workflows and production methods and answering questions for a team of people – that I haven’t fully been able to zoom out and get an idea of what that looks like. I don’t want this to sound like it is coming from a place of ego, because it’s coming from a desire to be generous with the world, but having witnessed just the sort of magic that happened in my own life and in the lives of 13 people that I work with now at this company, when I was essentially given carte blanche to design a system in the building in my own home… It feels like…Follow me here. It feels like the universe is the surface of a trampoline, and I have just pushed, with a single finger, as hard as I could in one spot, and all of the good people, like marbles, rolled into the gravity well. And I want more of that. I want to be able to do that at a scale that is not just like a house for one family at a time.. I want to do it in villages and neighborhoods and landscapes and cities and the transit patterns across them. This sounds grand, but it doesn’t actually feel like ambition at all, because I’ve witnessed the end result, and it is peace. It just feels like this deep desire to create more peace.

MD: That’s a really beautiful and a lovely way to end this conversation. It’s super inspiring. And I want to fall into the trampoline [laughs]. I’m there with you.

AF: Very nice meeting you, Max.

MD: Same here. Thank you, Andrew.

Left Image: Max Dowd picking up soil from construction dumpster for the Earth Bricks manufacturing. Right Image: Earth Bricks being manufactured, 2016-2020. Courtesy of the Architect.

*In architecture, the iterative process is often hailed as a crucial phase of design development. This method, characterized by repeated cycles of trial and error, is intended to refine and perfect architectural concepts.

To learn more about Max Dowd’s work: @vernacular.works // vernacular.works

To know more about Andrew Frederick: @croft_co2 // www.croft.haus

Max Dowd, Rammed Chair, 2024. Made From Compacted NY Construction waste and Natural Lime + Steel Right. Courtesy of the Architect.

Left Image: Max Dowd, Rammed Chair, 2024. Made From Compacted NY Construction waste and Natural Lime + Steel Right. Image: Max Dowd, Corner Shelf, 2024. Indigo dyed reclaimed wood from Big Reuse. Courtesy of the Architect.