João Livra: First of all, thank you for accepting the invitation. When Anita [Goes] spoke to me, I thought long and hard about who to invite for a conversation that would flow naturally. Someone I admired and had met a few times, both through our practices and our worldviews. She wasn’t familiar with your work in depth, but when I told her about you, she coincidentally had a meeting at Simões de Assis, your gallery in São Paulo. While chatting with the team there, she came across your work. It turned into a series of encounters, until she eventually visited your studio and got to know it more closely. So, for me, it makes perfect sense for us to have this conversation. We were neighbors, right?

Mano Penalva: Yes [laughs], in the same building.

JL: São Paulo has this strange dynamic of being neighbors without truly knowing the person next door or the one downstairs. The first time I went to your place, you had already moved to another building, and it was only then that our friendship really began to take shape. I also think it’s nice that we’re having this conversation because we’re in different stages of our careers. I’m still in the process of developing my work and don’t have gallery representation yet. And there have been some interruptions in my production along the way.

MP: Yes, and that feeling is closely tied to the market… In a way, we’re from the same generation, the same age, and we work in the same space [São Paulo city], right? But we have to be cautious with this idea that being an artist is defined by having gallery representation.

JL: Yes, exactly. Because, in reality, representation is no longer about us. But we do have a lot in common. Neither of us has formal academic training in art, for example. I find it really interesting how you approach your work with such professionalism, precision, and assertiveness. We were just talking about your book… and that requires immense effort and dedication. You’re a true reference for me when it comes to commitment to the craft, you know? My own journey has been less consistent. I’ve experienced some interruptions for various reasons, but it’s been more experimental in nature.

MP: It’s curious that in São Paulo, we come to know each other’s work through shared interests and the places we frequent. We’d cross paths in the same spaces, even outside the art world. When we first met, you were collaborating with Marina [Wisnik] and working with Chocolate Notebooks [a handmade notebook brand], and I think having other interests outside of art really enriches our work. Even simply walking through the city, as a practice, feeds into our creative process. We’ve often discussed how we encounter things on the street that are almost fully formed, or at least nearly so. In a way, finding something that’s almost ready and then making shifts to enhance it is a practice of sensitization – a way of training the eye.

Massapê Projetos, Mano Penalva’s exhibition space and studio, São Paulo. Center top: Gabriel Pessoto, blusão, 2025. Photo: Estúdio em Obra. Lower center: Mano Penalva, Alpendre (Duas pessoas caminhando na rua. Final de tarde.), 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Quase Espaço, João Livra’s former exhibition space, closed in 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

JL: Yes, an exercise.

MP: Exactly, an exercise. It’s not just aimlessly wandering around the city. This is deeply tied to the experience of our bodies—how we position ourselves within the city and how we are perceived and seen. I think this is closely connected to our personal trajectories, right? These are practices that precede where we are today and culminate in what we propose as spaces for thought, production, and artistic expression in São Paulo. You with Quase Espaço, and me with Massapê. I spoke seriously just now, but, at the core, this perception of the street is quite amusing. Many things you share on your social media – and that I share on mine – border on the absurd. That’s the first point where our practices intersect, where the interest and respect for each other’s work begin. It starts there, in that grace and attentive gaze toward the city. We live and work in downtown São Paulo, which is a perfect backdrop for this. I like to think that, between the smooth and the rough, we’re living in the rough. Full of folds, full of possibilities. Even though there’s an attempt at gentrification – and I don’t particularly like that word -downtown remains a place full of friction and endless potential.

JL: I really like this idea of the journey of sensitizing the gaze, which happens long before our production, and how we navigate these external spaces: the street, the market, places of encounter, and spontaneous creative energy. The other day, I heard Marcelo Cidade say that much of his work revolves around the journey between his home and the studio. He lives here in Santa Cecília, and imagine, on the way to Barra Funda, a whole range of processes and issues emerge over just a short distance. That’s part of the charm of being in Brazil, right? There’s so much space to explore. And here, improvisation is very much a part of our lives, which carries a certain irony. I often think about the Brazilian ingenuity when it comes to solving problems. I keep imagining durepoxi and wire. If we removed durepoxi and wire from Brazil with a single command, I think much of everything would collapse. But still, improvisation brings that laughter, that grace. Spontaneity is always surprising. And in this space of surprise and presence, there’s a sense of contemplation. I, like you, can no longer walk through the world distracted. We walk in a more open, connected state, and we recognize so many things, including materials.

MP: It’s funny that you mention durepoxi and wire. I also often think about masking tape, hot glue, paper clips, and staplers. In these everyday items, the street and the concept of home, of the private, merge. These are the things that keep everything standing, the power of realization, which is almost magical. I believe this is one of the greatest contributions of Brazilian art. We don’t create grandiose works, but we occupy this space of appreciating the minimal, finding significance in the minimal.

JL: And yet, within the realm of megalomania, we create the world’s biggest party—Carnival. If we imagine Carnival without hot glue, nothing would stay up. This drive and determination we have to keep things standing is what makes our creations monumental in our own way, right? Not to mention other improvisations, like bodies pushing a float that weighs who knows how many tons. I think this is one of the greatest virtues of our art, when viewed from a more global perspective.

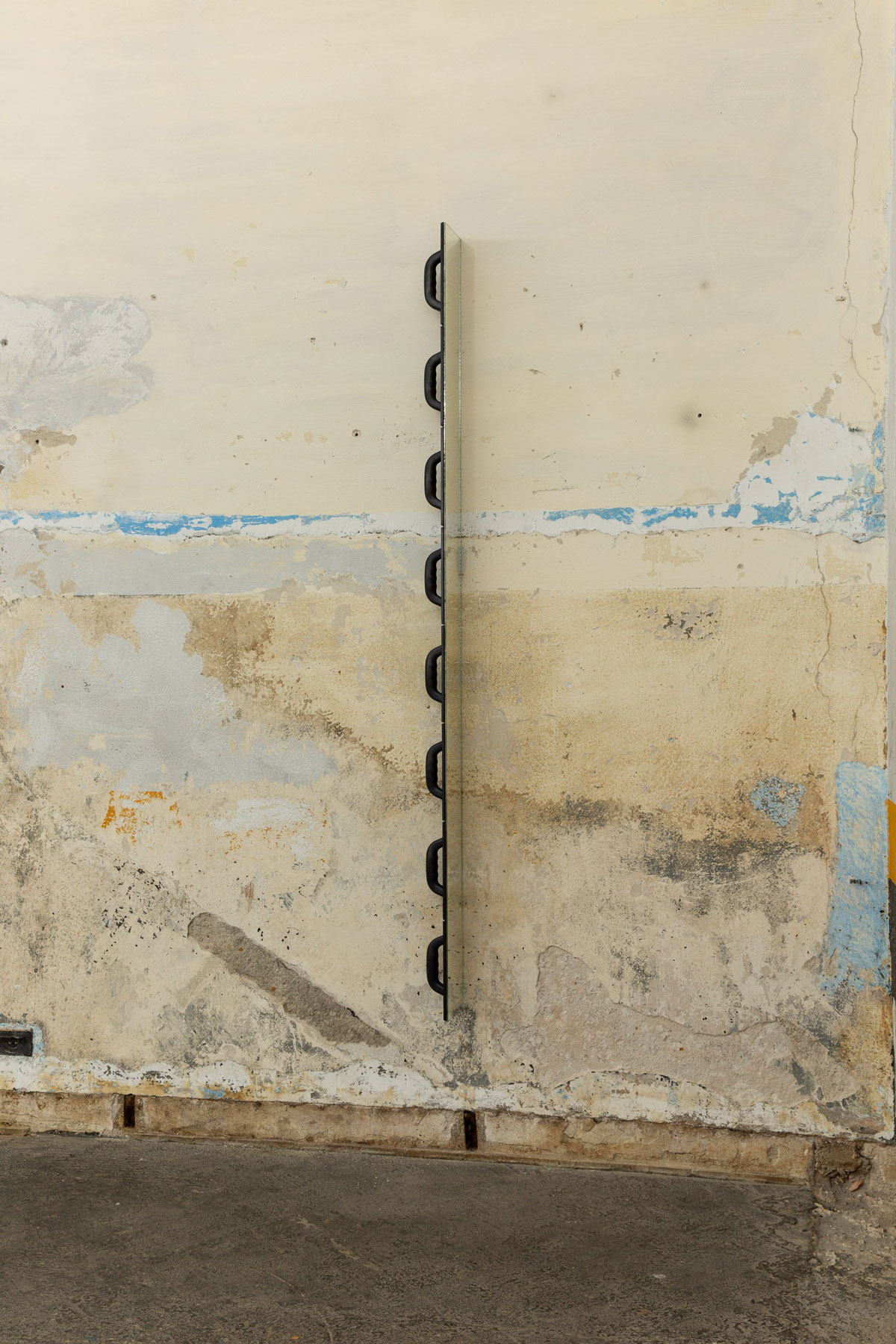

João Livra, Espaço comum, 2014. Exhibitive walls covered with wood (Madeirit plywood), variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

João Livra, Welcome, 2024. Galvanized steel shovels and tempered glass. Courtesy of the artist.

MP: I have this theory that Brazil should be the Silicon Valley of parties – whenever any place in the world needs a celebration, we should be the leading company to create it, charging premium prices just like a tech company..

JL: I agree! But that also brings in a bit of that “poison and medicine” dynamic, right? Because, if we approach it from a more social or even “corporate” perspective, as seen in other countries and external structures, all we seem to do is throw parties. We’d have to figure out how to properly price it.

MP: I think we should treat it as cutting-edge technology. In fact, I’m not entirely in favor of championing improvisation as a concept. While there’s great value in the “gambiarra” (improvised fix), there’s also an importance in the level of care that goes beyond just improvising.

JL: I believe that’s the key strength of Brazilian art. It carries the “gambiarra”—this joyful, inventive way of doing things—but what we ultimately present, often through hardship, is a refined and sophisticated result. I think improvisation in this context is similar to how we think about it in football. It’s not about doing things poorly; rather, it’s a resource to create the most beautiful, artistic play. While the infrastructure of sports is often poorly developed in our country, our football remains highly sophisticated. We can also see this in music… samba made with a matchbox, a plate.

MP: I prefer to think about it through the lens of music. I don’t know much about football, but from my perspective, our football talent has been overshadowed by a global, European professionalization. However, in music, we still deliver both technical and poetic quality.

JL: That’s an important point. The common critique is that Brazilian players went to Europe and lost the essence of Brazilian football, which is about playing for the joy of it. Music, however, hasn’t lost that root.

MP: What fascinates me most about how we manage to keep things standing is the technological aspect, the trial and error process. I think it’s powerful to consider these ways of living as a form of technology. For example, this week, the coffee machine here at the studio broke, and I needed to replace the spring. The spring itself cost R$40, and delivery added another R$69 – almost the price of a brand new machine. I was so frustrated. Since I couldn’t go without coffee here, I had to come up with a solution. I used a “enforca gato” [nylon tie wrap] to fix the coffee machine, and it worked. I was amazed. It cost me less than R$0.30.

JL: It’s a resource.

MP: That ability to solve things, right? We’ve been living with this for a long time. It also has a sustainability aspect, if you think about it. Here, discarding things isn’t immediate because they don’t cost so little. So, we look for solutions, repairs, and ways to reuse. We still fix a lot of things, and I think that resonates in how we think about and execute our work. And with that, we make these minimal and maximal shifts with almost the same intensity. Our practices stem from these small adjustments but reach poetic potentials and explore the poetic field. This is really the root of what we see at home, in the street, during those walks with a more engaged gaze. I also see you’re very interested in poetry – maybe a bit reserved with it, but from time to time, you throw one out there. And then comes the word, which is a key and powerful element in the realization of our practices. That “almost finished” thing we encounter on the street, in its almost state, still requires refinement. And often, it will need a name.

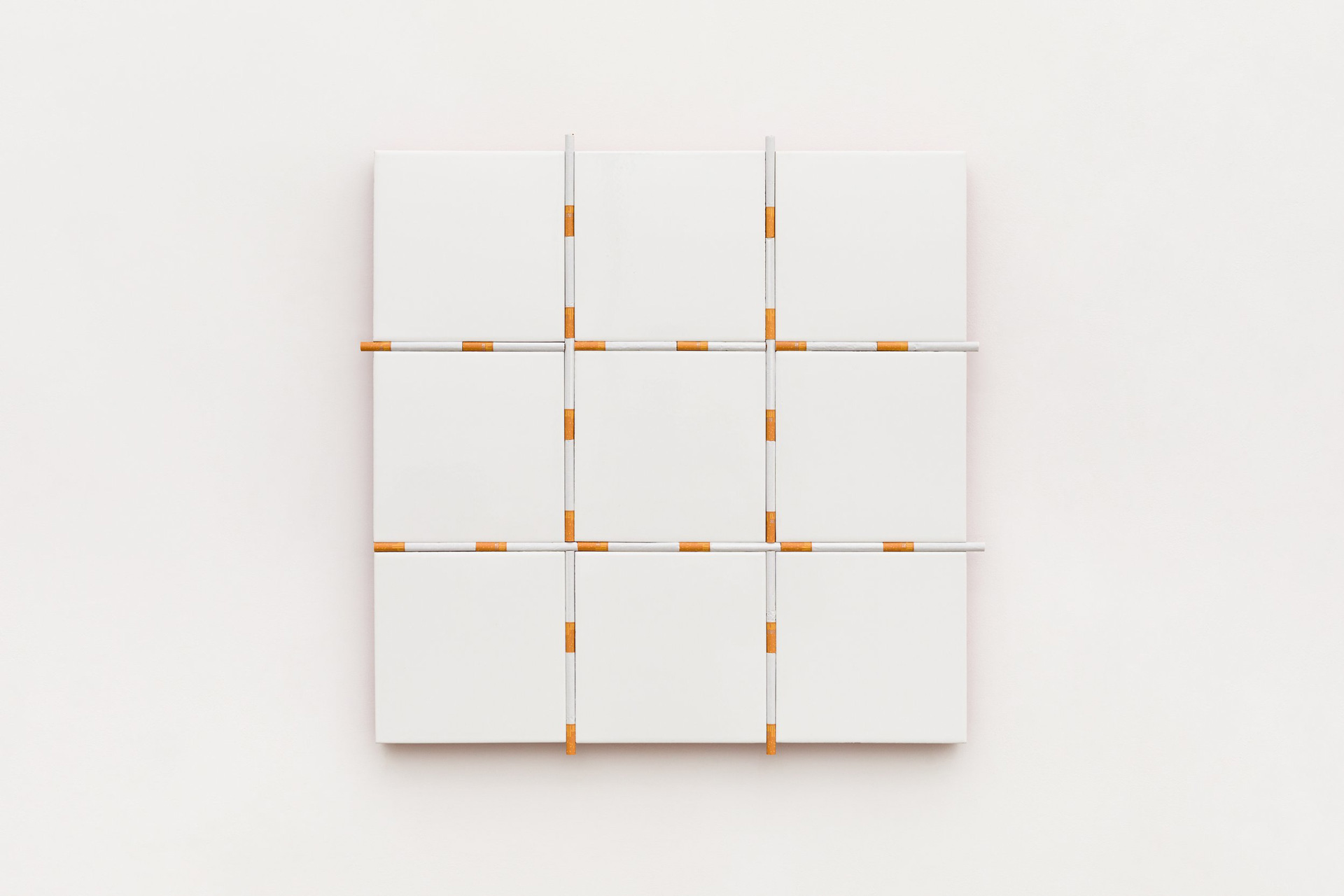

Mano Penalva, Regador, 2017. Resin, fiberglass, and iron powder, 20 x 20 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Mano Penalva, Bisel V: como arredondar quinas, 2023. Wooden beads, metal rings, ribbon, steel wire, and nails, 90.5 x 63 x 43 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Mano Penalva, Tribeira, 2019. Folding screen and shards of glass, 7 x 63 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

JL: A name serves to reach another place, another status. Whether through a photographic record or the literal reproduction of what we find, it’s in the displacement that the work truly takes form. It’s almost an intervention. In that context, the object is already “done,” but for the artwork and the artistic practice, this movement is necessary. I was watching a conversation with Alexandre da Cunha and Leda Catunda about the exhibition [Travessia] he recently presented at Galeria Luisa Strina. There was a piece called Encruzilhada, where he replicated the exact gate of a bench on Avenida Ipiranga. I had the memory of passing by that bench, but just the other day, I walked by and saw the metalwork in the same exact scale. Theoretically, I saw that gate in the street first. This is the power of displacement in establishing an idea.

MP: Is that the gate where he inserted incense? Is that the work you’re talking about?

JL: Yes, that’s it. And there was incense placed in it. He encountered it with a keen eye. And I saw it transformed into an artistic format, a beautifully resolved composition, yet still within its original context. In the end, the result manifested in me.

MP: That part of the city offers so much material.

JL: What a block! When I met you, about 15 years ago, we were at a fair in Vila Madalena, and you had these typographic posters. I grabbed one that said, “Long live downtown. Long live!” I still have it. We have this fascination with the place we live, but also a sense of responsibility. After I saw that poster, I started following the development of your research, and it makes so much sense. There was a core and an essence there that’s just unfolding, but always connected to the place where you live.

MP: Downtown holds the power of movement on foot. Walking satisfies me a lot—it makes me feel like I’m living in a big metropolis. I left home in Salvador, in search of a place where I could engage with that life or that idea of life, where I felt secure and immersed in all these stories. I’ve searched for that center in many other places, in New York, in Mexico… But, in fact, New York and Mexico are part of that center in São Paulo, just as so many other centers are. The multicultural diversity, the languages, the foods. I think it’s beautiful to see Asian or African foods arriving in the late afternoon, between 5 and 6 PM, at Praça da República, where the African ingredient stalls are.

JL: That aroma.

MP: Yes, it’s an aroma that makes it feel as though those things have just landed in Brazil, not as though they’re arriving through a local distributor. We are here and in the world at the same time, right? For me, there’s nothing more incredible than living that. All those accents, those smells, those arrangements. And what you brought up about Alexandre’s work… That piece also had a huge impact on me. I even told him that I’d passed by that spot a million times. It’s that old saying, “Everything has been done, everything exists.” But at the same time, we are producing, within contexts and conversations, different dialogues. Everything has been done, yet it will continue to be done and perceived. Our interest isn’t passive. And these works shift our perception of things, of life, of relationships. But I want to return to the subject of the word, and even mention your last exhibition here at Massapê, titled Burro. When I work with material, it’s like I’m expanding the way that thing lives in the world, and the word also has this power to expand or create new connections, even in the title of an exhibition or a piece. I have several untitled works, but nowadays, I rarely do that anymore. How do you approach naming your works?

JL: I’ve had some untitled works, but today I understand that the word is almost an adjustment. It complements the idea, object, or piece. I’m really interested in building poetry—I even have a book I’ve been dragging along for almost 20 years, hoping to release at some point. The word complements and opens paths for other interpretations, and sometimes it can be a sidestep. In that exhibition you mentioned, Burro, there was an effort to work with the word in a way that felt almost magnetic to the work. I have a series called Gestinho, which refers to that “jeitinho” we spoke of earlier, but in gesture. The title sometimes reinforces the meaning, sometimes distracts, but the word is always there as something complementary.

Lower center: João Livra, Indulto II, 2024. Saws and rivets, 12 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

MP: I knew you already had many poems ready, but not a book.

JL: It’s in eternal construction, right? I think it’s a lack of courage. Maybe I have more boldness to publish other works, art pieces, projects, spaces. But I have this respect and admiration for words, for the poetic construction, because it’s so intimate. In this archive of almost 20 years of poetic construction, there are various stages of life, different moments, and I still lack a bit of courage to finalize and share it.

MP: A lot of things are on the brink of happening. I also wanted to talk a bit about Quase Espaço, a space you created, where you’re proposing exhibitions for the city and facilitating conversations among artists. On my side, I have Massapê, where in seven years, we’ve held 35 exhibitions. These spaces have become part of our artistic practice. I see them as a desire to create other types of conversations, in different ways, and maybe that’s connected to the fact that neither of us has an academic art background. When we opened Massapê, Santa Cecília wasn’t as…

JL: Hyped [laughs].

MP: Exactly, hyped [laughs]. The neighborhood was curious about what this space was about, and I feel that has changed a lot. We don’t receive as many visits from the neighbors anymore.

JL: That more spontaneous vibe, right? Back then, Santa Cecília had a very unique energy, almost a small-town atmosphere. Any renovation would spark some buzz: “What’s happening over there?” In the building where Quase Espaço is today, we were more of a shock than a curiosity. We’d open, and the neighbors would be like: “How can so many people be here on a Thursday night or Saturday afternoon? What are they doing?”

MP: People here are also shocked. It seems like we’ve arrived at the height of the buzz now. My first studio in São Paulo was on Rua Frederico Abranches, and then I moved to Vila Madalena, but I came back here because I didn’t quite find myself in Vila, in terms of spatiality.

JL: Let’s agree that the gentrification process we’ve talked about has already progressed in Vila Madalena.

MP: There, it’s a smooth space, with commerce already more organized, consolidated, and with very internationalized references. When I first came here [to Santa Cecília], cars didn’t even pass by the street, there was no parking meter. And now, suddenly, there are so many cars — and of different models. Our proposals serve the city in a way. I’m so happy when people stop me on the street and ask what the next exhibition is.

JL: People are connected to it.

MP: Our space is small, our communication is basically only on Instagram. But we do it with so much passion. We’ve had exhibitions by people who are still in or have just left university, as well as by people who have exhibited in biennials in Brazil and worldwide. This mix of opportunities, possibilities, and conversations between generations is, for me, one of the most powerful things you and I are bringing to the city with our spaces.

JL: Yes. I manage Quase [Espaço], and I’ve been thinking a lot about the purpose of it… I ask myself: why am I doing this? And until now, I don’t have a very clear answer. It’s something that really commits me, both financially, in terms of time, and with the demand for work. And we’re in a very expensive city where we rarely get private support or public funding initiatives. It’s not a viable business model — it’s not a commercial gallery, it’s not an institution. But we started talking about the street, and that makes me think that maybe these spaces of ours came from a desire to bring what we find in the street to an internal space, somehow. To amplify exchanges and encounters, to create unexpected connections. And then, maybe almost “unintentionally,” with many quotation marks, we end up making noise in the market and institutions, displacing the street to a private physical space.

MP: Listening to you say this, I was thinking about the gesture… In our spaces, we don’t just open the door, we lift the door.

JL: Exactly. The moment of lifting the door to the street is what matters. In our spaces, we don’t have as many obstacles, like stairs, entrances, security… we’re in a neighborhood where people walk. When you lift the door, Massapê almost becomes like a street. But it’s a job that wears me down, and at the stage I’m at today, I really need to prepare myself to maintain the space, beyond the financial question and all the other problems. People come with the expectation of showing their work, and that care takes a lot of energy.

MP: Yes, aside from the practical things, like keeping the space clean, the most sensitive part is managing expectations, because we’re dealing with different generations, different desires.

JL: And in a time when everything moves so quickly, which heightens that anxiety.

MP: And with younger artists, there’s a market-driven need. The need to sell to continue, to survive, or for the possibility of connection to the market. Some artists have passed through here and later gone on to show their work in galleries, succeeding in their careers and showing their work in other spheres. And I’m really happy to have been the bridge. That care has to exist. But it’s also really beautiful when, on opening nights, we lift the door and people are standing between the street and the house. The intimate and the public become one. What’s inside goes outside, and what’s outside comes in. Some nights, 200, 300 people show up at the opening, and when you stop to think that the communication is just on Instagram, it’s a phenomenon of word-of-mouth. I have a motto when I invite someone to exhibit: “Treat it like it’s the best institution in the world.” Even though we don’t have smooth walls or a perfect structure… in the end, it’s the same because it’s about your power as an artist. You can impact people here at Massapê, at Quase [Espaço], or at MoMA. I’ve seen amazing things at Massapê. And because it’s an unpretentious space, there’s also room for experimentation and a certain freedom.

JL: Thinking about how many people are producing, at various levels and stages of production, that’s the most important point for me because I think it’s in experimentation that the artist’s power stands out. Maybe your work will go to other places where you won’t have the same freedom to experiment. Do you have a clear sense of the purpose of having this space, Mano? How do you see Massapê in a few years, considering you have your work, your career, and many demands?

Mano Penalva at his space Massapê Projetos, São Paulo, 2025. Photo: Estúdio em Obra. Courtesy of the artist.

MP: I came to this space with the desire to share. For me, this is essential. In fact, Massapê is the name of one of these tropical Brazilian soils that, although not as fertile as the red earth, played a crucial role in Brazil’s development in terms of planting. The name, in a way, evokes an idea of Brazil. When I arrived, the space seemed very large – today it feels smaller, and we have to exercise a certain kind of architecture to fit everything. Since I thought the space was large, I wanted to share it with others. Initially, my desire was to bring artists from the Northeast, because I found it very difficult to find windows to show my work here, and I understood that the space was something I could contribute. So, I started doing that. Even though it hasn’t been long, seven years ago there weren’t many spaces to exhibit. After the pandemic, other spaces and collective studios started to emerge.

JL: Even though it’s a short time, it’s hard to find a space that lasts this long. Talking to other managers, I’ve concluded that three years is the average lifespan for these spaces.

MP: Yes, that’s true. But today, I also see Massapê as part of my artistic practice, you know? I have a connection with Mexico, and one of the most beautiful movements of the 90s, La Panadería, involved a group of artists who would meet to translate texts from English to Spanish and talk about their artistic practices. One of them, Damián Ortega, eventually founded the Alias publishing house from this, producing cheap books to spread art knowledge, and today he considers that part of his artistic practice. Massapê is sustained by renting the space to other artists, and that covers the basic structure costs.

JL: It’s not a business that generates any profit, right?

MP: No, it’s really an investment of time and money. And that’s also why I see Massapê as part of my artistic practice. And political, but not just mine, because, in reality, it’s only possible through exchanges with other artists.

JL: A space can’t sustain itself without building a community – of artists, of the public, and so on.

MP: Yes, and part of the fulfillment I get from this space comes from making the artistic practice a little less solitary, both for me and for the other artists. Currently, we propose two exhibitions, and with that, we open up a conversation and an interface to visit other studios. It’s a place with the purpose of sharing this achievement of having a space in São Paulo and proposing exchanges and dialogues. But it’s also a very personal fulfillment.

JL: It’s curious. I come from a family that didn’t consume art or culture, and I had little access to that in my education, so my practice started much later in life. But I’ve always carried this desire to create space within me. As much as it’s an enormous challenge, the idea of doing something collective gives me this energy, you know?

MP: You have this beautiful energy of transforming spaces. That’s a characteristic of yours that I admire a lot. You arrive and propose an aesthetic for the place. I think these spaces you’ve created in recent years have one thing in common—they have the peeling walls.

JL: That’s about equalizing the desire to create with the resources available. By taking advantage of what architecture and structural space offer, you can forgo fine finishing. Any space can become a space when someone wants to build and show their work.

MP: But I think that just reinforces your desire to propose these conversations with aesthetic quality, but above all, with a lot of courage. My grandmother used to say: “Just go in, ask for permission, but just do it.” It’s about diving in. When I see Massapê full… These spaces also exist to share courage.

JL: We have so many artists with amazing work and a huge demand for spaces. Why do you think there aren’t more exhibition spaces in São Paulo?

MP: I think we have about 20 or 30 spaces in São Paulo, and they propose different things. But there’s this temporality you mentioned, with an average lifespan of two to three years for these places. In these seven years of Massapê, I’ve seen many open and close, but also some emerging and staying, like Fonte, Canteiro, and Vera 184, for example.

JL: I tend to think that what we have is very little, very scarce. We have a lot of willingness and little resources. Quase [Espaço] itself is always on the edge, unsure if we’ll be able to sustain a program for a semester or a year, or if we’ll close*. And it wouldn’t take that much in terms of resources—just what’s available to create a healthier ecosystem with more possibilities to show work and create exchange points, you know?

MP: Support is always welcome, but Brazil doesn’t have such a strong, established culture for that, right?

JL: Not from private support, nor from institutional support, which is also common in other parts of the world.

Top center: João Livra, exhibition view Pátina Amarelo-suja – Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade, 2014. Lower center: João Livra, detail Pavimento, 2014. Paraffin and mold for concrete modules. Courtesy of the artist.

MP: In terms of institutions, this might impose regulations that we may not necessarily want. It would be extremely important to have some for the visual arts to ensure basic rights and guarantees, but other areas would also need regulation. But is that really the realm of art? How much do we want regulation, and how much do we want our freedom? That wild experimentation brings us so much too. There are places in the world where there is significant access to public funding for the development of public spaces, but you need evaluations from stakeholders, other artists, curators, and state members, which ends up leading to a lack of critique of the system. That seems a bit dangerous to me.

JL: It really is dangerous. Too many personal interests… and again, it brings us back to the public vs. private debate and how to mediate and navigate between both in a positive way.

MP: I think about this constantly. For instance, brands that could be associated with our program with small support, offering a beer, a drink, or water at the opening. And it’s a huge struggle to even get in touch with the brand. We know we’re offering much more than the value they invest in, say, 200 beers. The symbolic capital of what we offer, proposing that the brand be linked to an exhibition… and 200 beers are nothing for a global brand, you know?

JL: And we’re not talking about any kind of significant financial investment or anything that would affect their budget sheet. It’s just about supporting in an almost indirect way, right?

MP: Exactly. I’m not willing to beg for scraps. We’ve had various beverage brand sponsorships, and in the past few years, they’ve practically vanished. I’m not willing to send 20 emails and 20 WhatsApp messages to get 100 beers. I’d rather buy the beer myself, or the artist brings something, or we put up a PIX for the public’s contribution. I wish this conversation was easier because this is a trade and a proposal for the city and culture. What we’re doing has a very rich propositional role.

JL: There’s always this attempt to bargain, and in the end, we end up doing it ourselves. But I think this also touches people. And too bad for the brands that miss out on this; I’ll admit I’ve tried every way to seek support.

MP: In this hostile field, our work is very encouraging. I think our work is a bit like acupuncture. We’re placing those needles, freeing up the city’s blood flow, the culture. I see it with a certain freshness. It’s beautiful, man. We need spaces to start and to believe in what we’re doing. I want to keep mine for as long as possible.

JL: Yes, it’s so important to inspire. We have our difficulties, and they’re not few, but it’s undeniable the energy and contribution these spaces offer.

MP: I really admire the work of Sandra Cinto and Albano [Ateliê Fidalga] and what they’ve been doing in recent years. I think I’ve been inspired by that place and by Fonte. The dedication of a lifetime. I once heard Sandra talk about perseverance in artistic practice… A few years later, that’s only grown stronger for me. Believing in your work, in what you’re doing. That’s a micro-politics, in a way. Our spaces aren’t just spaces; they are mediums. The space may cease to exist, it may change address, but it remains a medium.

JL: I think this is a great way to wrap up, emphasizing the importance of perseverance. Cool! Thank you Mano! I really enjoyed the conversation.

MP: Wonderful! Thank you as well.

Mano Penalva, exhibition view Cumeeira, 2023. Simões de Assis, São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist.

To learn more about João Livra’s work: @joaolivra_studio // joaolivra.work

To know more about Mano Penalva: @manopenalva // manopenalva.com // simoesdeassis.com/artistas/mano-penalva

To keep up with Massapê’s agenda: @massape_projetos

João Livra, Sujeito dividido, 2023. Convex mirrors. Courtesy of the artist.

Right image: João Livra, detail Estaca Rothko, 2024. Two-tone paraffin candles and twine, 59 x 2 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

* Closing Note from Quase Espaço

After three years of intense activity, Quase is ending its operations. There have been more than 30 exhibitions, residencies, and projects that have helped strengthen the independent contemporary art scene, offering a space for experimentation, dialogue, and exchange. From the beginning, we aimed to open paths for a diversity of languages, voices, and perspectives, welcoming artists from different backgrounds and fostering plurality in thought and creation.

We believe that every artist, collaborator, and visitor who passed through here contributed to the creation of something meaningful, which will resonate beyond the physical space. We continue with the certainty that our impact remains in the connections and reflections we helped to provoke.

Our deepest thanks to all who were part of this journey.

Thank you very much,

João Livra.

João Livra in front of Quase Espaço, 2022, São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist.

João Livra has held solo exhibitions such as Pátina Amarelo-suja (Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade, 2014), Desinteligência (Quase, 2022), Forte Abraço (Delirium, 2023), and Burro (Massapê, 2024), in addition to participating in numerous group exhibitions across Brazil.

Mano Penalva, A benção, 2016. Chair, cane webbing, and coast straw, 39 x 59 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

In recent years, he has participated in several artist residencies, including Casa Wabi – Puerto Escondido (Mexico) 2021, Fountainhead Residency – Miami (USA) 2020, LE26by / Felix Frachon Gallery – Brussels (Belgium) 2019, AnnexB – New York (USA) 2018, Penthouse Art Residence – Brussels (Belgium) 2018, R.A.T – Artistic Residency for Exchange – Mexico City (Mexico) 2017, and Pop Center – Camelódromo Porto Alegre (Brazil) 2017.

Hero Image: João Livra, Voss, 2022. Bottles of mineral water and adhesive tapes. Courtesy of the artist.