Reading How to Listen to Jazz by Ted Gioia, I was taken by a great example of this difficulty — and a suggestion on how to try and be more sensitive to such breaking points in the arts. Gioia was trying to fully grasp the genius of Louis Armstrong. His solution was not to listen to all of the musician’s records, but instead the opposite. For a couple of weeks, the writer restricted his listening to only jazz from before Armstrong’s time. When he finally allowed himself to listen to Armstrong scatting, the shift was clear! And everything Gioia heard after Armstrong immediately reflected this new paradigm. It’s a before and after situation. To me, Betty Woodman represents a radical change in the arts – a before and after Betty Woodman.

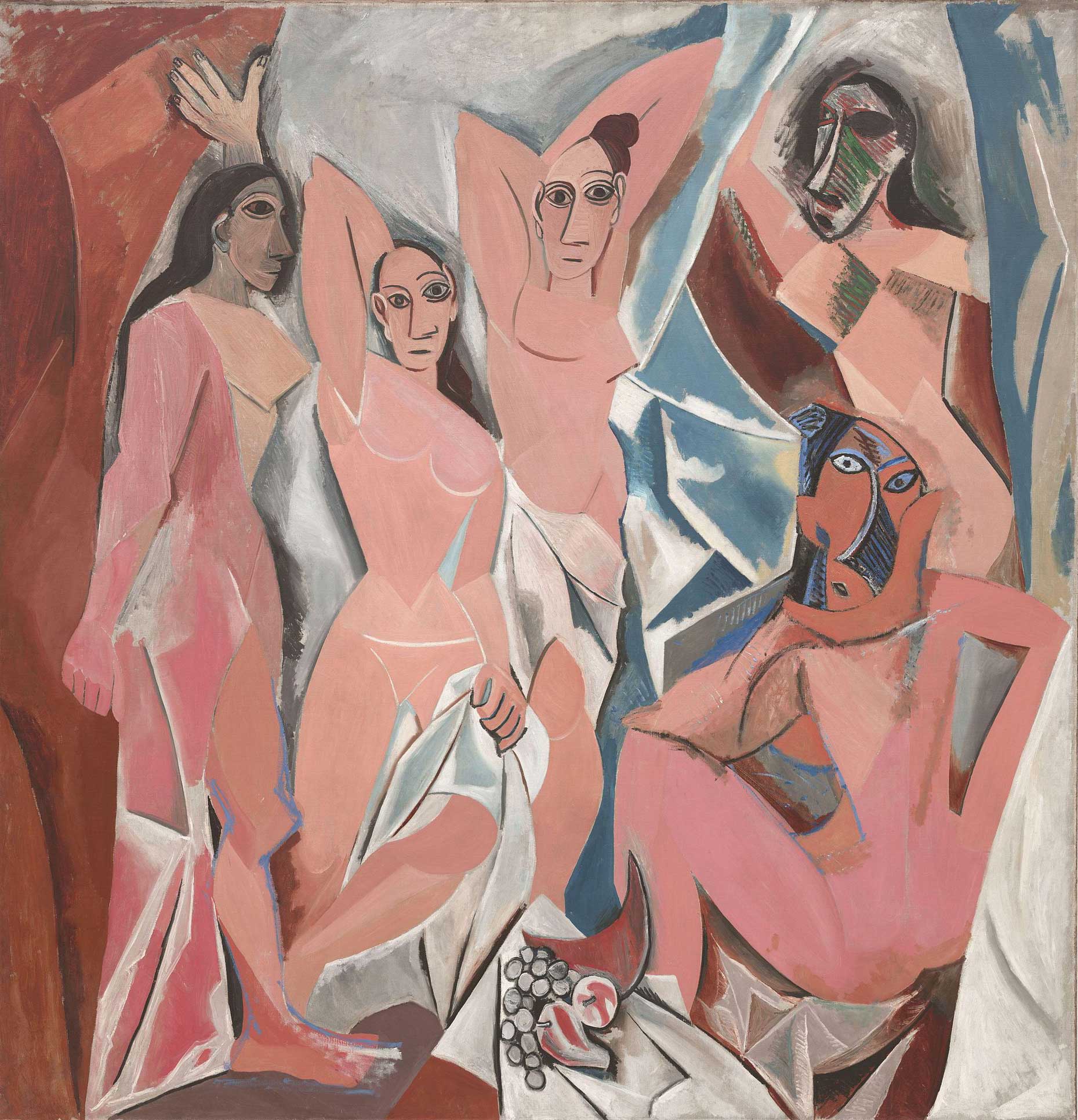

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, Oil on canvas

Born in Connecticut in 1930, Woodman split her time between New York City, Boulder, in Colorado, and Antella, in Italy. The first time she touched clay in high school, at age 16 – she made a pitcher. In an interview to the Archives of American Art in 2003, Woodman mentioned that while in school, during World War II, she also made model airplanes, “including a Messerschmitt, for air-raid wardens to use to identify German aircraft”. After concluding The School for American Craftsmen, in Alfred, NY, in 1950, she starts dedicating her energy to pottery – still focused on functional stoneware, bowls, plates, cups and saucers. She organized sidewalk sales twice a year when she lived in Boulder.

Woodman was also an activist for clay. And in the mid 1950s, she convinced the City of Boulder to create a pottery program. The city government decommissioned a Fire Station and started the country’s first city-run ceramics school. In the beginning, there was one class a week in the evening, with less than 10 students attending. In the documentary “Woodmans”, Betty appears in 1991 recalling: “Fifteen years later, there were 400 students taking classes in 8-week sessions. It became a very big program.” The initiative attracted some of the most talented ceramicists in the US, and became a national model for other city parks and recreation program. Also in the 50s, she starts spending part of every year living and working in Italy, with that country’s traditional ceramic style becoming incorporated by her.

Betty Woodman and George Woodman at Betty’s kiln, Antella, Italy, c. 1996. Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation Archive.

Betty Woodman, Hydrangea, 1987.

In January of 1981, the artist Francesca Woodman, Betty Woodman’s daughter, takes her life, at age 22 jumping out of a New York City window. While coping with grief, Betty stopped making only functional pottery and started exploring what would later become her trademark vessels. “How did I deal with the guilt?” she asks in the same documentary, “I tried to stay away from it. Because I think there’s no way to deal with it.”

Around the same time she began moving on from only functional pieces, Woodman started looking for a representation as an artist. She partnered with Max Protetch, who was a dealer famous for showcasing architectural drawings. Protetch was used to that gray area between function, craft and the fine arts. Her first show at Max Protetch Gallery took place in 1983 and they worked together until the 2010s.

While Woodman developed her career in the East Coast, a more male-oriented world of ceramics was also sprouting in California. Woodman referred to ceramicist Peter Voulkos and his colleagues as being very “macho”. At the same time, she talked about how vases – the archetypal ceramic object – are also “a symbol for a figure, a woman. Metaphorically, it’s a container; it has that connection for everyone.” Author Ursula K. Le Guin has a beautiful text from 1986, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, where she relates the invisible “domestic” work of women and the womb and breast shaped bowls they made throughout history. Le Guin redefines how important these artifacts were for the survival and development of our race.

Betty Woodman in her studio, Boulder, Colorado, 1961. Photo: George Woodman, courtesy of the artist.

Woodman’s relevance is clear when she becomes the first living female artist to be the theme of a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum, in the Summer of 2006. The Art of Betty Woodman covered the artist’s career, from her early works of the 50s and 60s through her mixed-media pieces of 2005-2006. In the museum’s page about the show, we read: “The vase was her earliest – and over time, it has become her most salient – subject. For Woodman, the vase can be a vessel, a metaphor, or an art-historical reference. Her work alludes to and infuses numerous sources, including Minoan and Egyptian art, Greek and Etruscan sculpture, Tang Dynasty works, majolica and Sèvres porcelain, Italian Baroque architecture, and the paintings of Picasso and Matisse.”

I like to think that even the airplane models influenced her, and some of her vessels literally look like eccentric big birds about to fly. I remember the first time I saw her work, at the Whitney Museum, in NYC in the 2000s, and was transfixed. The glossy surface, the colors, the outrageous expansivess of the vessels taking over the wall, their wings spreading. The label, describing the vase on a shelf, titled Hydrangea, from 1987, said something along the lines: “according to the artist, this piece may or may not be used as a vase.” The flexibility, the embracing of the limbo between functional design and museum level art felt warm. The existence of her pieces in any space are like a blooming rose, striking us with its fertility and sultry aspects. If “a rose is a rose is a rose”, as Gertrude Stein wrote, my feeling is that “a vessel is a vessel is a vessel”. They are pure poetry and presence — indescribable. Woodman treats her ceramic pieces like paintings. Not only by the way she paints them with bold colors, but also by creating installations on the wall, filling the space in a way I never imagined a clay piece could.

Betty Woodman, Tables and Vases, 2006, glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer paint;

Betty Woodman, Seashore, 1998, glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer paint.

Betty Woodman, House of South exhibition at Salon 94 gallery, 2021.

C. Richards (1916-1999), a poet, writer and potter who taught at the experimental art school Black Mountain College in the late 1940s, has a book on pottery that covers the topic with philosophical approach. In one of my favorite passages, Richards recounts a Chinese fable:

A noble is riding through town and he passes a potter at work. He admires the pots the man is making; their grace and a kind of rude strength in them. He dismounts from his horse and speaks with the potter. ‘How are you able to form these vessels so that they possess such convincing beauty?’ ‘Oh,’ answers the potter, ‘you are looking at the mere outward shape. What I am forming lies within. I am interested only in what remains after the pot has been broken.

Beyond celebrating how important process is, we could use this fable to reflect on how invisible being revolutionary often is. Once someone shifts the paradigm, it is so hard to imagine the world without their influence. We may struggle to think it wasn’t always so. We take it for granted.

Betty Woodman, Still Life Vase #15, 1991, glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer and paint. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery.

Betty Woodman, Venus #7- Homey, 2014. Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery.

Betty Woodman in her studio in Antella, Italy, 1996. Photo: George Woodman. Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) had a similar effect – reshaped our understanding of the interconnectedness of nature so profoundly, that we cannot imagine a world where this wasn’t the case – so much so, it becomes easy to ignore the power of his findings. “He pioneered the notion that the natural world is a web of intricately entwined elements, each in constant dynamic dialogue with every other — a concept a century ahead of its time. His legacy isn’t so much any single discovery (…) — as it is a mindset, a worldview”, as Maria Popova explained.

To me, Betty Woodman is part of this team. Louis Armstrong, Alexander von Humboldt and Betty Woodman. If we are now used to seeing clay sculptures, vessels and ceramic installations ubiquitously, it is because there was Betty. Her powerful vision goes beyond definitions of high and low art and includes changing an entire city, and then a country’s, relation to the medium. We need Betty and her wings.

Louis Armstrong, 1965.

Elizabeth Woodman born in Norwalk, Connecticut (May 14, 1930 – January 2, 2018) was an American ceramic artist.

Gisela Gueiros is a Brazilian art historian, art advisor and educator based in New York since 2007 who founded her roving gallery Gisela Projects in 2021. Since 2013, she has organized more than 40 independent art shows, and has collaborated with major Brazilian galleries. Her art tours of New York’s gallery districts and museums, as featured in the pages of New York Magazine, Folha de São Paulo and Vogue Brasil, have become essential engagements for tourists and residents alike since 2010. In addition, she has been invited to curate shows featuring artists Alfredo Volpi, Elizabeth Jobim, Paulo Pasta, Dudi Maia Rosa, Chiara Banfi, among others. In 2020 she curated multiple exhibitions for the new virtual platform Preview — co-founded by curator and art historian Gabriel Perez-Barreiro. Gisela has worked as an educator for the Guggenheim Museum and as a guide for Artful Jaunts. She is also a mother of twins, a ceramicist and writes a weekly newsletter.

@giselagueiros www.giselagueiros.com // https://giselagueiros.substack.com