Her archive extends over decades and continents. Whether she is in a field in Venezuela or a child’s beauty pageant in Tennessee, her photographs are distinct, and the artist’s personality makes space for true human expression. It is as if we were catching people in their off moments, but in no way like a camera was present. I feel like an eavesdropper, but there is a calmness to her subjects and etiquette in her interactions that makes me feel like I won’t be chastised for looking.

The work is about the vulnerability people must share for survival. Love for the untouchable, for the victims of abandonment, displacement, and narcissism. Sometimes, a glimpse into her photographs sears my skin and wrenches my gut. I resonate with the images that feel uncomfortable. The pictures give us space to feel at one with our awkwardness and wallflower tendencies, and they cast empathy, knowing we are all carriers of trauma and dysfunctional coping mechanisms. We feel the discomfort of being human and being recognized or perceived. We are confronted with our deepest fears through the eyes of the distrustful.

Greeting others worldwide has made Rosalind an authentic communicator, and her exposure to different cultures emanates through her archive. Rituals and superstition thread throughout and allow the viewer to find congruence to their ways of celebrating or mourning. How we value beauty and what we deem worthy is a reflection of ourselves. In her subjects, I see people who have been hurt. I see people full of hope. I feel isolated and comforted, seen yet insignificant. I’m learning to recognize my value reflected in my surroundings and the people I allow myself to be confronted by. I am hopeful for a hand on my shoulder when the times are hard. When don’t they feel that way?

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Lila, Jenin, Israel, 2010.

I sit in a pile of her books and feel the depth of her achievement portrayed in the publications of her work. When presented in a book format, sequencing becomes an emotional labor to create passageways. Subjects fold into the foliage or lend their gaze directly to ours. We see mothers of all kinds, lovers of different sorts, and fresh ways of considering how a face can form. You can taste the wealth discrepancy between subjects, but on the stark white page of a book, they are equalized. Rosalind’s voice guides and directs us through the pages.

“I talk while a part of me

is in another place

saying something else.” —from THEM

I return again and again to an image from the West Bank of a blind woman named Lila dancing and smiling. In this scene, the figures behind her, the shadows emerging from her shoulders, and the walking stick give the subject six legs, taking on a deity quality. Later, echoed in the book, is a quote proclaiming, “Sometimes I think I am god.”

In the book Liberty Theater from 2018, I gasped with delight every time I saw this image. (Ringgold, GA). Every individual in the frame is their own character; even the slide of elbow we see on the edge of the frame signifies a particular player in the atmosphere of this room. We are in an off-kilter moment, knowing not if it is Halloween or just another night of playing dress up in the living room. The figure in the clown costume stands on the couch but casts an ominous presence over the family, who look completely content. The beer, the child picking his nose, and the mom in curlers all line up vertically with the battle stick the clown is holding. Each time I look at this image, I see something new. I also wonder how Rosalind was invited into their home that evening. Sometimes, I forget there’s a photographer in the mix because of the intimate level we are included in in the images.

Her portraits, often assisted with a flash, place her subjects into otherworldly zones as if they are made of wax. We are invited to look but do not gawk or dawdle. Pay attention, but do not stare. Rosalind allows us to peek without shame or danger but with respect.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Ringgold, GA, 1976.

Her landscapes are also about people. About what we leave behind, how we affect the land, and the imprints we make. We can see ourselves in fragments of bodies, in embraces, and distances between us. We see the same emotions repeated throughout her practice: a discomfort quelled by touch or invitation, a quest for joy no matter the circumstances, and a longing for inclusion without fully committing.

We see the silhouette of Lady Liberty, scaffolded. I can recognize her body’s shape and monumental reach, literally and metaphorically. Within the scaffolding, she appears at once safe and robust but somehow less immortal than in other photos. She rises above the shoreline, but we have yet to determine how far she is from the ground. The human element of restoring a project completed almost 100 years prior encompasses how I think about history and how photography plays a role in how we remember. Our memories are fragile, and we can uncover their depth with the support of images.

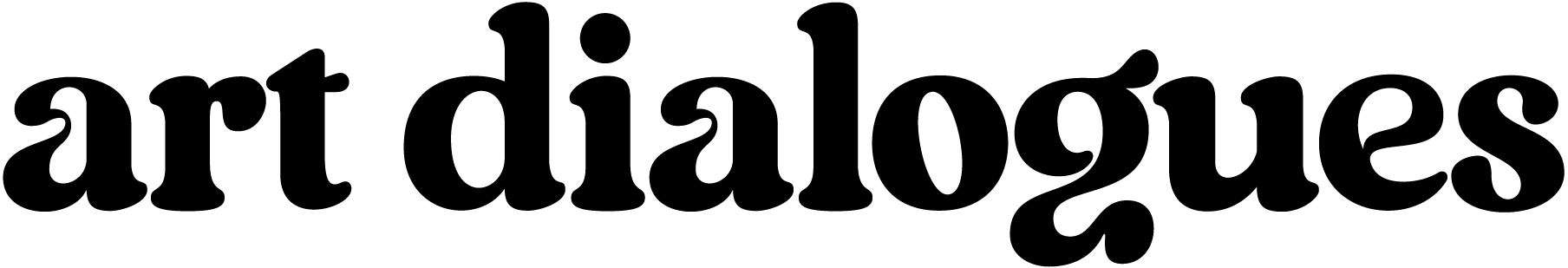

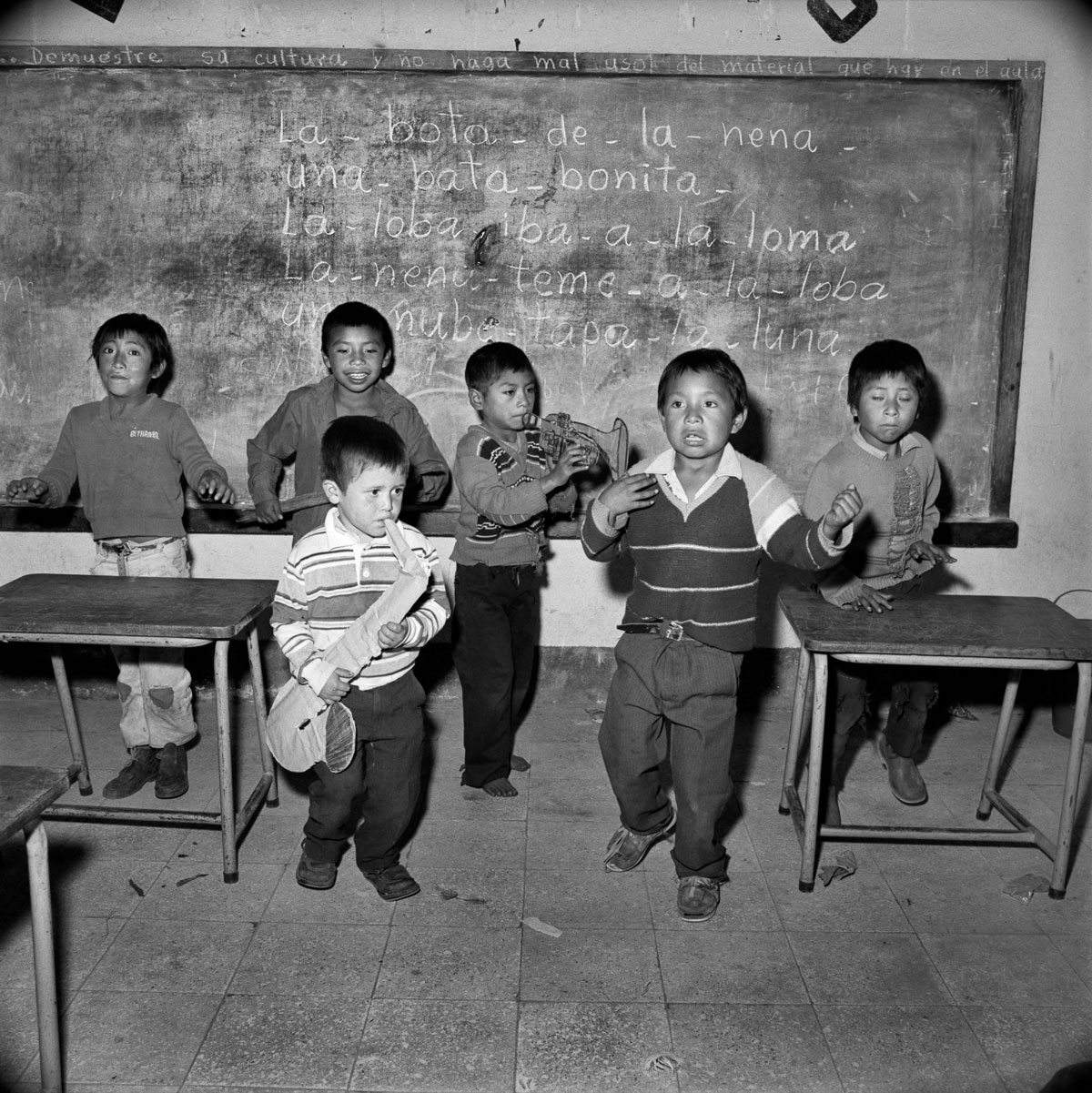

My copy of The Forgotten has a chewed corner from an ex-boyfriend’s dog. I prefer it wasn’t damaged, but I find myself laughing at the circumstance and know that this life of material things is temporary. My least favorite images are in this book. I feel my heart cringe and my pelvis tighten, looking at the image of a man shoving dollar notes into a woman’s face. I feel enraged each time I see it. It must be in there. We turn away at disfiguration and punctured sockets but then return to an empathetic and cheerful place. There is an image of children playing paper instruments in Guatemala. I can hear the tapping of the drummer’s fingers on the desk and the deep breaths caused by a face-encompassing smile. Rosalind understands how to access and portray emotion.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Statue of Liberty, New York, NY, 1984.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Paper Band, Totonicapán, Guatemala, 1992.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Cremation, Katmandu, Nepal, 1985.

A series she completed in 1988, Portraits in the Time of AIDS, is intimate and glaring and one of the most important bodies of work the artist has created. The photographs give a voice and create a legacy for these subjects who have long since passed, and Rosalind depicts the love present when the world otherwise shunned and hurried away from them. There’s a gentleness to these images. Everyone looks unburdened with the thought of being witnessed. Others recognize her otherness, and I can see how her presence champions disclosing secrets to make you feel safe. When we speak of death, we are prepared to access this inevitable feeling of unknowing.

The light doesn’t care that your body is failing. The flash will find its way into the conversation and highlight the positives of each scene. The dappled daylight on a delicate sternum creates a tension of acknowledging the cyclical nature of everything. Rosalind’s close attention and care for those with mere days left on Earth has perhaps karmically extended her stay here.

When I am with Rosalind, I feel inclined to tell her the hardships I’ve experienced because she has also met many variations of death. She confronts her own body in battle and continues to win. The pandemic panic usurped her 90th birthday party, and I remember the cancellation of the event standing out as one of the most important milestones to be corrupted by the news. Four years later, she is producing a new book of self-portraits.

Despite our almost sixty-year age difference, I see myself in her. The images she has made of her own body throughout the years is nothing short of inspiring. Her investigative look into the vessel that carries her is treated in the same documentary style as her other work. You can hear the lyrical demands and voice of Rosalind’s mother echo throughout her media and begin to understand how it shaped her identity within herself. The mother wound sits deeply in us, and her work about her family and their expectations provides insight into the artist’s criticism throughout her life and the epic rebellion of following her path. Imagine your mother telling you to stop blinking. I can still hear “I remember when men stopped looking at me and started looking at you” from my own memory bank.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Nick and his Mother, Portraits in the Time of AIDS, New York, NY, 1987.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Self Portrait with Frozen Turkey, New Hampshire, 2002.

She speaks about this conditional love from her parents and how that imparts to us that we are undeserving of a certain level of pride, fame, or accolades. The urge for the artist to return to photographing dolls repeatedly signals this fragmentation of childhood. I see it as a desire to recreate something she lacks. We return to comforting elements, deliverables that can feel charming when feeling fear of responsibility or not knowing what to do. The unknowing, the sabotaging of future happiness, is something I relate to in Rosalind’s images.

I am honored to know and love this photographer and am grateful for every second I get to spend with her. We speak of life and health together and the tragedy that sometimes life breaks us down before it takes us away. We discuss how a peaceful death is a privilege in a world of turmoil. To me, she is incomparable.

Rosalind Fox Solomon belongs in the history books, and her archive is a source of empathy in photography and what it looks like for someone to follow their heart. I am excited to watch her continue to accept and celebrate her accomplishments and marvel at the archive that will live on in books and prints, celebrated by exhibitions and others returning time and time to this loving archive.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Chattanooga, TN, 1974.

Frances Jakubek is an image-maker, independent curator, and consultant for artists. She is the co-founder of A Yellow Rose Project, past Director of the Bruce Silverstein Gallery in New York City, and past Associate Curator of the Griffin Museum of Photography in Massachusetts.

Recent curatorial appointments include Critical Mass, Potential Space: A Serious Look at Child’s Play featuring works by Nancy Richards Farese, Filter Photo, The Griffin Museum of Photography, British Journal of Photography, Les Rencontres d’Arles, Save Art Space, and Photo District News.

To know more about Frances Jakubek: https://www.francesjakubek.com/ @franciepants

Hero image: Rosalind Fox Solomon, Self Portrait, MacDowell Artist Colony, 2002.

Frances copy of The Forgotten book with chewed corner.