Laziza Is the Party Lebanese Food Deserves

Editor: Anita Goes

Words: Sylvia C.Jorge

Photo: Jack Pompe & Justin Walker

Illustration: Arthur Daraujo

Brooklyn, 2025

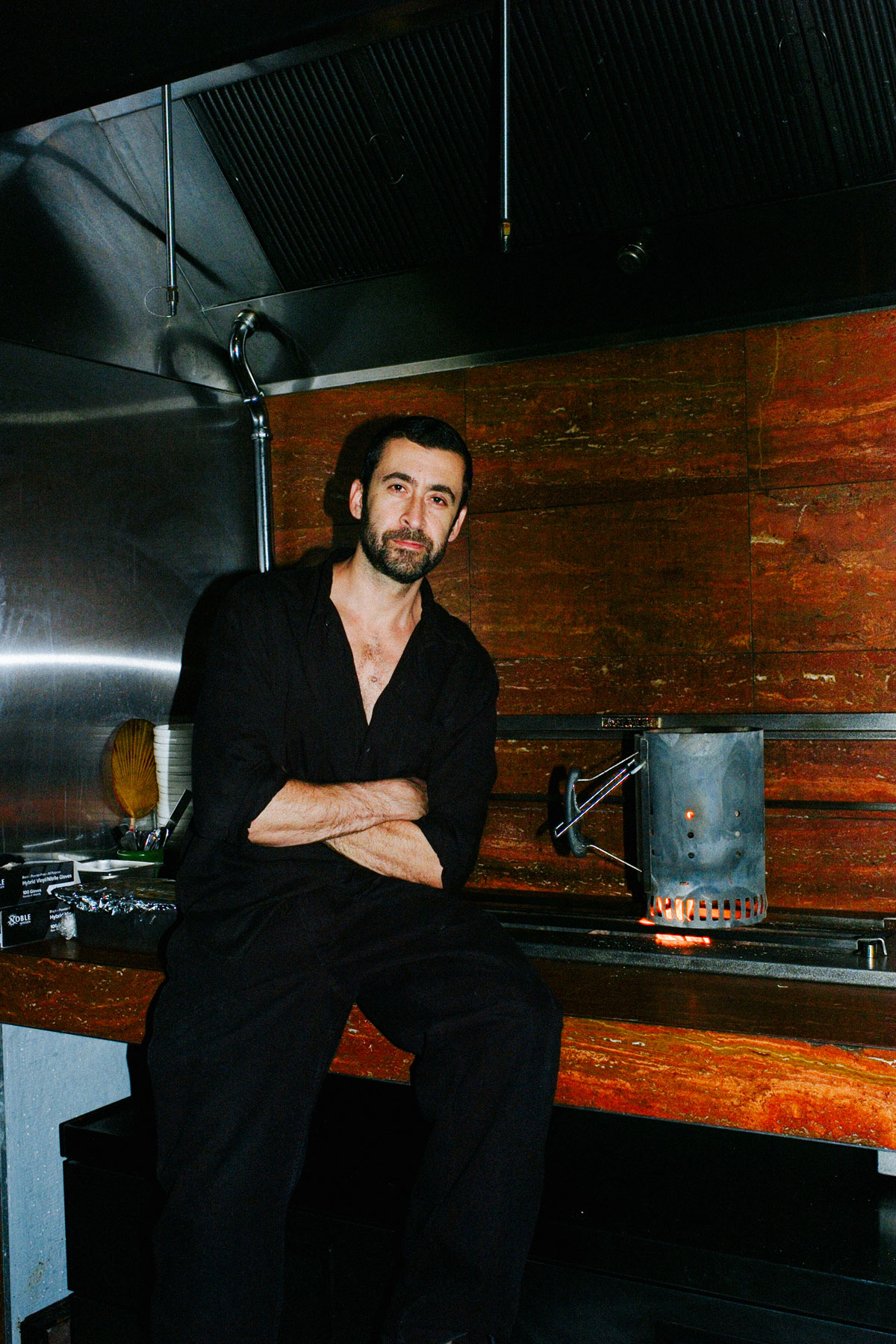

In Bed-Stuy, Jilbert El-Zmetr is throwing a dinner party for the entire Lebanese Diaspora

There’s something about Laziza that feels like more than a restaurant the moment you step through the door. Tucked into a lively stretch of Brooklyn, it’s a place where drinks, music, and mezze come together under low-hung lights and the sound of vintage vinyl spun on an old-school setup. You might show up for the lamb meshweh, or the whipped labneh topped with zaatar chilli crisp, but you’ll leave talking about the stories — Jilbert El-Zmetr’s stories, to be exact.

Born in Australia to Lebanese immigrant parents, Jilbert’s culinary journey is less about recipes and more about inheritance — of migration, of flavor, of curiosity, and above all, of hospitality. Laziza (which means “delight” or “good thing” in Arabic) is his love letter to that inheritance, and to the generations of Lebanese cooks, hosts, and storytellers who came before him.

“Food, to me, is never just about eating,” Jilbert tells me on a late Monday afternoon in Dumbo. “It’s about how the plate got there. What made this dish what it is? Who carried it across the ocean, and how did it change along the way?”

Roots in Roasted Lamb and Shawarma

Jilbert grew up in Sydney, where his family found a foothold in a vibrant Lebanese immigrant community. His dad, a classically trained French pastry chef from Beirut, eventually opened a fish and chip shop — the family’s first business in their new country. “That’s what you do,” Jilbert says with a shrug. “You cook what the people around you eat, then you build your own flavors into it.”

They did just that. Before long, they pivoted to a shawarma and falafel spot, where young Jilbert could often be found perched in the back with his homework, watching his father marinate meats and his mother wrap sandwiches. He remembers the chaos as natural, not stressful — the rhythm of family and survival.

But it wasn’t until years later, after a career in software engineering and a decade living in Hong Kong and China, that Jilbert began to feel the pull toward food as a deeper calling. “In Hong Kong, I became obsessed with the idea of what Middle Eastern food really is,” he says. “The way Chinese cuisine changes from region to region — we don’t talk about Levantine food like that, but we should.”

Booza and the Beginning of a Journey

In 2018, that curiosity took the form of Republic of Booza, an ice cream shop in Williamsburg where Jilbert reimagined traditional Lebanese-style stretchy ice cream for a modern New York audience. Inspired by a Damascus ice cream store where he’d watched the dessert being made by hand, Jilbert reverse-engineered the technique, designing and building his own machine in Hong Kong to replicate the pounding and stretching that gives booza its signature chew.

Before it became a Williamsburg storefront, the booza project first took shape in Australia. Jilbert developed the recipe and technique in Hong Kong, then partnered with his sister back home to produce and sell it to supermarkets. She ran the day-to-day operations, while he focused on perfecting the texture and flavor from afar. “It was a way to test if people outside the Middle East would connect with it,” he says. The experiment worked — shoppers were intrigued by the dense, stretchy ice cream, and it gave Jilbert the confidence to imagine booza on a bigger stage.

“I didn’t open the shop to sell ice cream,” he laughs. “I opened it to tell a story.”

Though Republic of Booza closed in 2021, it was the first public chapter in Jilbert’s now-expanding narrative: Middle Eastern food as migration, as adaptation, as memory. “We had flavors inspired by everywhere — Brazil, Africa, China, even classic American flavors. It was about making connections,” he says. “We need those stories as much as we need the flavor.”

Building Laziza: More Than a Restaurant

After Booza, there was a brief pause. “I had to ask myself — what do I love? Not what makes sense, not what’s easy.” That clarity led to Laziza, which began as a six-month pop-up in a neighborhood coffee shop before finding its permanent home. The concept: a space that felt like home, that centered on Lebanese hospitality but remained unafraid to evolve.

Laziza is part-restaurant, part-bar, part-music venue, and all heart. Jilbert built it with the help of his father, who flew out from Australia to help construct the space — a full-circle moment that ties generations together through wood, spices, and speakers.

Laziza’s menu is rooted in Levantine tradition — think creamy hummus, crunchy falafel, lamb meshweh — but it doesn’t stop there. “It’s not about replicating Lebanon,” Jilbert says. “It’s about translating its spirit.” That might mean arugula where there would traditionally be purslane, or a dish of fried chicken dressed with Turkish cheese and sumac. There is no burger, and never will be. “That would be telling the wrong story,” he says simply.

What you will find is a space that pulses with life: DJs spinning global funk and Middle Eastern disco on weekends, collaborations with nearby cafés, and plans for an expansive backyard with dance parties and rotating chefs. “We’re only eight months in,” Jilbert says, “but it already feels like a living thing.”

A Trip to Brazil, and a Wider Lens

This summer, Jilbert traveled to Brazil — invited by Art Dialogues magazine, a platform committed to sparking cultural exchange — to dig deeper into the Lebanese diaspora and how it’s evolved in another corner of the world. Brazil is home to the largest Lebanese population outside Lebanon, a fact that fascinated him.

“I grew up with the idea that Australia and Brazil were the two major diasporas,” he says. “But what I found in Brazil was totally unexpected.”

Through a connection with Diogo Bercito, a Brazilian scholar whose PhD focuses on Syrian and Lebanese migration and culinary influence, Jilbert was introduced to restaurant owners and chefs across São Paulo. He met Leila, a fourth-generation Brazilian of Lebanese descent who runs a restaurant called Arabia. “She’s this incredible woman, fluent in Arabic, Portuguese, and English, who just carries this whole history in her kitchen.”

Then there was Samer and Mira, a young Lebanese couple who fled Beirut’s economic collapse in recent years. Both trained architects, they opened Libaninho and Lulu with a fresh, modern take. “Their flavors were the closest to what I know from home,” Jilbert says. “But their presentation was new. It was exciting.”

He noticed how Lebanese food had become part of Brazilian culinary DNA — sfihas sold on delivery apps, kibeh rebranded as street food, and “Beirute” sandwiches that don’t actually exist in Beirut. “It made me think about how food changes, how it becomes something else — and that’s okay,” he says. “The stories don’t have to stay fixed. They can move.”

He’s bringing some of those insights back to Laziza, maybe even in the form of a Middle Eastern riff on Brazil’s beloved feijoada.

“Why not?” he says. “The pork would go, but the technique, the layering — that’s something we can play with.”

Laziza: @funkylaziza

Sylvia C. Jorge @sylviabkny

Jack Pompe: @jack.pompe

Justin Walker: @behindthedawn

Arthur Daraujo: @arthurdaraujo

Lebanese Hospitality as Compass

If there’s one constant in Jilbert’s globe-hopping exploration, it’s the value of hospitality. “Growing up, we had a room in the house that was only for guests,” herecalls. “Kids weren’t allowed in. That was sacred.”

He’s brought that reverence to Laziza, where the mission is less about food and more about how it’s shared. “We’re here to welcome you. That’s the essence of Lebanese culture,” he says. “Even if you don’t know the cuisine, you’ll know the feeling. That you’re welcome.”

That philosophy threads through everything — from the carefully selected ingredients to the music (“Dancing is part of it. Why wouldn’t we dance?”). Laziza isn’t just a place to eat. It’s a place to belong.

At Laziza, Jilbert isn’t just serving food — he’s building bridges. Between generations, between continents, between the memory of Lebanon and the energy of Brooklyn. Each dish, each record, each glass is an invitation to come closer, stay longer, and be part of something larger than a meal.