Bruno Passos: Where do we start? (Laughs)

Fernando Marar: I don’t know, we can talk a bit about how we ended up here. You and I are connected by this thing that is so symbolic, abstract, and that organizes everyone’s life, which is Time. I think we started way back in a design studio — you were coming from the countryside, I was coming from Bauru. The large metropolis of Bauru that encompasses Marília, a small but very valuable city that has produced magnificent people like you. (Laughs) We were able to witness our own revolution, wouldn’t you agree?

BP: Personally, my greatest interest in this conversation is not knowing where it’s going or what the purpose is. It seems that for you it’s the opposite, you like things in a more subsequent way, with cause and effect. I perceive your goals and paths are shaped by logic. This also happens to me to some extent, of course, but I don’t want to know how, because every time I understand what I am doing, it takes away a bit of the element of emotion of the artistic creation and leads me to focus on craftsmanship. It’s when I’m hyper aware of what I do, that I end up feeling less natural in my movements.

It’s as if I’m more interested in staring at the sky, waiting for lightning than knowing that lightning will strike at 7:52pm. I like the promise more than the thing itself, so my relationship with Time is to exist in it, without being aware of it.

FM: I find that amazing. I’m curious… when you lived in Marília, did you already have this awareness? At what point did this perspective arise, the desire to see the lightning rather than try study it? You have always been a studious guy, and I want to know the “why” of things. For me, this turning point is almost the shift from pragmatic thinking as a designer to the artistic thinking that you carry today.

BP: I think the strongest things in our lives exist without us knowing how they exist. You love your mother, your father, before knowing what the word love is or its meaning. And the problem with knowing the meaning of things is that when you name or categorize something, you risk limiting its scope or depth. For me, nomenclature, symbolism, it’s a kind of shortcut. Naming things and creating symbols allows us to have complex relationships with people, what we call a “conversation”(laughs). But, simultaneously, nomenclatures and their specificities diminish emotions.

Think about a recipe; if you read that recipe today or in fifty years, it’s very likely that your perception of it will be practically the same. Now think about doing this with poetry; I guarantee that it will have an almost unprecedented change if read within this time frame. This is because poetry is a less utilitarian, it’s more of an expansive arrangement.

Fernando Marar (left) e Bruno Passos (right) in conversation for Art Dialogues, Camburi, São Paulo, 2023. Courtesy of the artists.

FM: I understand, perhaps poetry is one of the few, if not only, ways to use words without ending something. Is that what you’re trying to do with painting?

BP: Yes. For me, poetry has a lot to do with artistic living.

FM: When I name something, maybe that’s the end of it, in the broadest sense. The first thing our parents do with us is give us a name. We are not born with an innate language ability. After you learn to think linguistically, that is an inseparable part of our existence. Maybe in your work, it’s already different; your expression is visual, you don’t use words per se. Do you think this relationship of wanting to see the lightning more than understanding the lightning, for example, has always been natural, or was it an effort within your artistic pursuit?

BP: Definitely an effort. When you create a symbol or a language, you can appropriate it to a certain extent, stretch the meanings; it’s quite a power. So, when I started, my idea was exactly to instrumentalize, make all my development pragmatic. “Why does volume happen, temperature, light, darkness, and saturation?” I wanted to understand how to tame these things. To improve, you need to start small and caged, that is, create symbols and orbit around these symbols because then you have a reference point to navigate. And it’s only from that reference point that it’s possible to develop. Every time I mastered an artistic tool, every time I understood how to create light or a vanishing point, I could stop thinking about it, and doing it became more organic. And because it became more organic, I noticed that sometimes I broke some rules, and that’s where it became possible to create “untamed” things, truly powerful and personal.

FM: Thinking about everything we’ve talked about throughout our lives…I can’t say that you are heading for an abstract path of painting, but there is something of that in the process. You’ve been talking for some time now about Dance, and I think earlier today at the coffee shop, I could understand that painting the lightning without knowing when it falls (and having a rapid way to react to it) is almost like your body dancing to music. The abstract is condensed in a millisecond; if it doesn’t come at the right time, everything collapses. It takes time for us to decode the feeling, transform it into words, but the more we exercise, the faster this transmutation is. Recently, I resumed writing, and I play with the idea that writing is “recording time in space,” so I started developing this purposeful writing in a notebook, where I basically write where I am, the day and time – that’s when I understood the power of intention. You went from the path of mastering the technique, which was a way of “studying the lightning,” to a new path of wanting to feel the lightning, right? Today, you have the agility and tools to record the moment when this lightning strikes, translating it as sensitively as in a dance, imprinting this lapse, which is your condensed emotion.

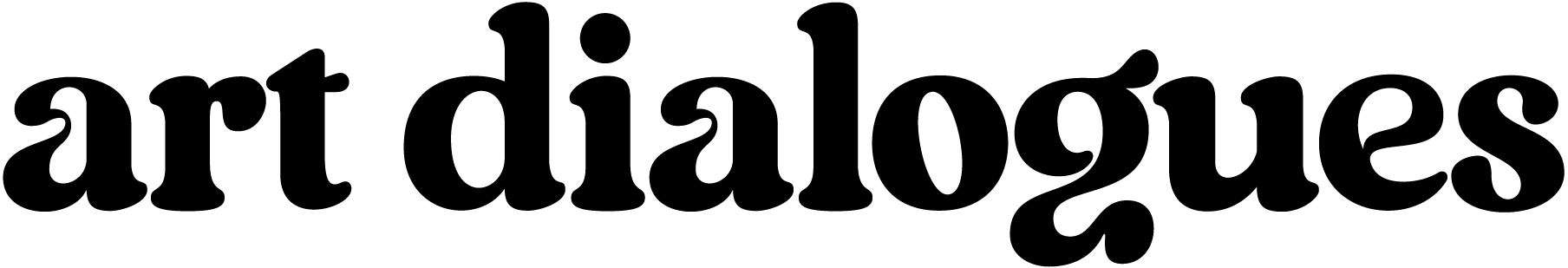

Courtesy of the artist.

Bruno Passos, detail of the painting Leandro, Acrylic on canvas, 51 x 31.5 inches, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

BP: This is precisely the main point that made me not want to be an illustrator – without disrespecting the profession. I don’t want to describe; I want to show, does it make sense? For me, showing the thing will always be more powerful than describing it.

FM: We never know where these conversations will take us. And we’ve reached a point that I wanted to touch upon, which is Time as a measure. It used to take you four months to complete a canvas, sometimes two months. Some artists took ten years to finish a painting. Now, I think about photography; it captures it in an instant. Especially analog photography, which is an image physically recorded on paper. It’s beautiful because you also understand the poetics of a photographer when they capture that moment and how much they trained to understand the composition and capture those moments. Before the lightning strikes, its eye is so prepared to translate exactly how it would like to see it. So, it doesn’t matter if it’s figurative or abstract, right? What matters is being able to express that sensation. Talking about Time as a measure, what are you trying to do by “ending” Time and projecting it more permanently? Photography does this masterfully well. In this sense, an analog photo, for example, allows, with an absurdly fast capacity, to record everything in a very clear and realistic way.

BP: I think that if I have a photo that captured a great moment, and that moment was our “lightning,” it’s there describing the moment with scientific precision. But when my eyes were seeing that lightning, the sensation of it went beyond Cartesian visuality. In other words, when I looked at it, the angles of the lightning were sharper in my feelings, and the brightness was stronger. It’s as if the photo, in a way, didn’t encompass everything I felt when seeing the lightning.

FM: That’s because the photo usually has the lens, right? Painting transfers that lens function to your hand.

BP: Exactly. A latent difference is more common to see in good painting than in good photography, which is an aesthetic vision. When I talk about Aesthetics, I refer to the etymological origin of the word, which comes from Greek and means “comprehension of the world through the senses.” Painting allows an aesthetic view of the scene, while photography allows a more descriptive view. Due to the malleability of painting, I can make it express what is more real to me in terms of feelings, while in a photo, it’s very common to show it to someone and then quickly add, ‘but in person, it’s different.’ Why does this happen? Because we’re talking about Aesthetics, about understanding the world through the senses.

FM: Interesting. I think there are even more complex instances when we move from realism to abstract. Shallowly, there is the abstract that people see other things, which almost becomes a figuration for that person. There is a mixture of figurative and abstract, which you also resort to at times. There is a more realistic path where you started. I think almost all great painters started there and dedicated a lot to technique. If you take Picasso or even Paul Klee… And then, this goal of wanting to paint somewhat like a child seems to arise. Today, I see this as a desire to return to a period where there was a different understanding of language, an embryonic place where the essence of the artist might be, but with already developed skills. This artistic quest is to want to walk in time- to look forward and find one’s own back. To write about the future, revisiting the past through the present. And this says a lot about time. Thinking about time as a unit, producing a painting is a kind of freezing of time, regardless of how long it takes. When you start painting the abstract, the unit becomes more about here, the now. The abstract is sometimes more difficult to interpret, but it seems much more faithful than realism from the perspective of someone trying to express a fraction of a moment.

I am trying to explore these transitions. As a designer, Time is a schedule that helps me prepare projects and organize myself. You sometimes also do this, for example, when you are going to have an exhibition. But I notice that you are increasingly close to the moments. How is it for you to deal with these two measures of Time?

Pablo Picasso, The Artist’s Mother, pastel on paper, 1896. 21 inches x 16 inches.

Bruno Passos, Azul Maré, Acrylic on canvas 59 x 39.4 inches, 2023.

Courtesy of the artist.

Bruno Passos, Cupido, Acrylic on canvas, 51 x 31.5 inches, 2023.

Courtesy of the artist.

BP: I think Time has become a social agent for me more than anything else. It’s my connection with the other; it’s a social measure. It’s not a measure of facts, but the vehicle through which I flow to find currents (which are people) with whom I want to converge. When we think about Time, sometimes we think about ourselves, about how I thought this or that, but for me, it’s irrelevant whether my afternoon lasts six years or ten minutes, whether this happened yesterday or a decade ago. Analyzing life in this way is just masturbation. What really matters is that time exists only at the point of intersection, at the moment my flow intersects with the flow of others, and this can only happen if we have some common denominators, such as language and, of course, Social Time. I can’t live in a very different time zone from you if I want to relate to you because we are animals, and we sleep at a certain time, eat at a certain time, and think better here or there. So, for me, everything related to Time comes from the other. My interest in knowing that the holidays have arrived is because I know that in this space-time called “holidays,” I will meet some dear people. Time is more of a meeting point than a measure of the passage of something. Thinking about time as a unit, what I want is exactly to unite with someone. Time is a line of communion.

FM: Dealing with time from the language has these ambiguities. “- Unit.” On my side, I am still a designer and pragmatic, thinking of time as a unit, like 30-minute boxes that I have to use to optimize things. I have always been afraid of death, and the word Time began to terrify me, you know? Because time ends… We say that Time is abstract and infinite, but our Time here is finite. And I think part of my anguish, after years of therapy and various processes that happened in my life, culminates even in us being here today, talking as part of this artistic dialogues project. When I was invited by Anita (Goes), I thought, wait, do you see me as an artist? And, in fact, maybe my work on nostalgia is what led me to want to talk about Time. Because the word nostalgia expresses Time. And it distresses me. (laughs)

BP: What bothers you about the notion of Time ending? What is the problem for you?

FM: I think it’s about existence, which was the point for which I have now rediscovered writing.

BP: Why?

FM: Because if Time is this thing that encompasses everything, the great umbrella, Time is a representation of God, right? And where do we face Time? On the calendar, but the calendar doesn’t seem like a good translation of Time.

BP: That’s why the plurality of meanings is so cool. Because this difficulty in definition makes things untamable.

FM: That’s the point I’ve been questioning. We use words to formulate a sentence, but in the everyday way of those who master speech, we ignore the real meaning of the words that compose it. This conversation, for example, uses many words to discuss only one of them, Time. And words like Time strongly impact how we organize ourselves as a society. Then I look at the calendar and think, why does the month start on the 1st and end on the 30th? Why is it always ending? Couldn’t we say that Time is growing? The month is ending… it’s death! At least from a very particular perspective, Time is always ending. A deadline. I have been trying to write because I felt that it needed to exist in some way. I don’t care if people will read what I write in the future or not, but if there is any convergence with someone who is going through the same thoughts and emotions, that will be very satisfying.

BP: You are connecting in Time with another person. So, do you agree that Time is a social unit?

FM: Yes, and I have come to understand the side of design that can lean towards art, as well. I know it’s totally different from your approach, but when I develop more personal work, with a more artistic approach, I try to somehow abolish the pragmatism of design, but I confess it is a tremendous effort. I realized that there are things I feel that can resonate with others and vice versa. When I arrived at the Donald Judd Foundation in New York, I came across the furniture. His idea of making the table, respecting the relationship of space and the proportion of the window, for example, resonated with me. In a way, I encountered a perspective from how I also see the world, and that touched me.

I think that’s when I understood a bit of the difference between Design and Art, in a way. One thing is me making a dictionary about Saudade, another thing is me pasting the word saudade anywhere in the city, and people stopping there out of nowhere because they relate to it.

Judd Foundation, New York.

BP: Design tends to seek definitions, right?

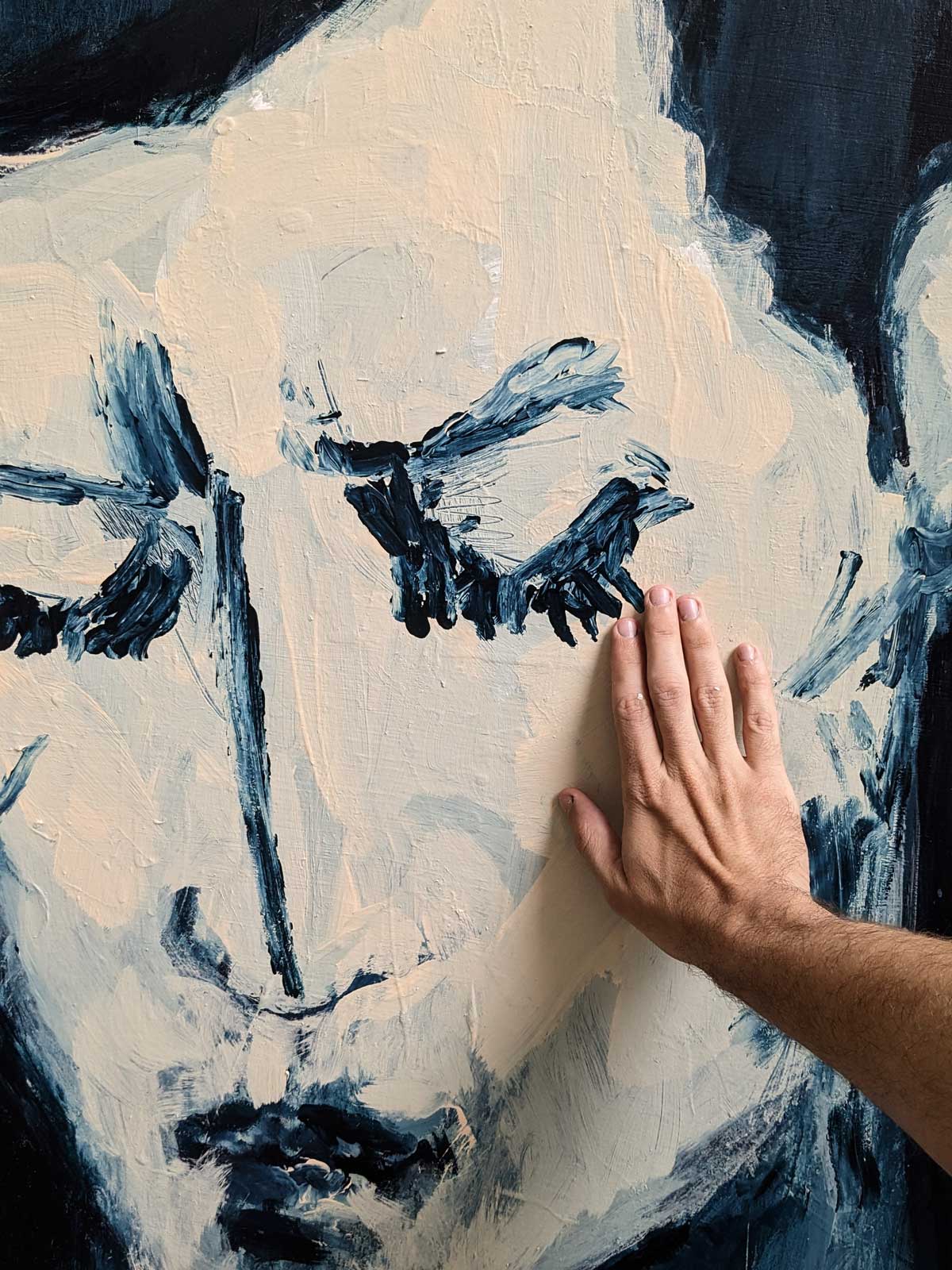

FM: Exactly, but Saudade is something very broad; it can be this place we are now, it can be you, it can be an apple, a smell that is bad for me and good for you. The only way I found to “paint” Saudade was to demonstrate it represented by its seven letters in sequence, and people who can read this image can project their own saudade there.

BP: This happened when you were willing to let the “thing” continue in the other. Personally, this is the big difference between Design and Art. In Design, you intend for that person, through the created design, to reach the standard coefficient you expect. It’s a very controlling thing in terms of function. This allows you to have sharpness but at the same time a smaller amplitude. And often, to be very profound, you have to give up the range of reach. Art often has depth but less reach. Instead of reaching 10,000 people, a painting may only reach two, but those two will be impacted powerfully. On the other hand, think about a glass; it will have to serve the ergonomic purpose for all those 10,000 people, some more than others. Design seems to have this need for futurology; it needs to predict what reaction it will cause and the consequences.

FM: The basis of design boils down to two questions for me: why and how. When I talk about saudade, I don’t carry these questions as much. This came to me on a trip I took to visit Igor, a friend I hadn’t seen for some time. He was one of my last friends from college to leave Brazil, and I felt a huge rupture in our Time-Space as a group of friends. I felt that things had changed. That feeling that maybe I would never have something back caused me pain, but during the days I stayed there, I started to meet people who didn’t have that word in their vocabulary. It speaks a lot about Time, a very affectionate Time of memories. Time is also in this roll of memory. Saudade expresses Time as language. That’s when this desire to explain this word to people who don’t speak our language came up, and from there all this curiosity about language, which brought me to the word death: Time and how we deal with it. Why do we still want to keep so many things? Record the place I am, the date and Time, and then go back to this paper on another date and place… all this is to say, “- look, I existed, I passed through here!”. This started to improve my relationship with finitude. And you, thinking about your work, how much does painting help you relate to life?

Fernando Marar, Saudade, silkscreen on paper, 26 x 38 inches each poster. Brooklyn, New York, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Fernando Marar, Saudade, silkscreen on paper, 26 x 38 inches each poster. Unibes Cultural, São Paulo, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Fernando Marar, Saudade, silkscreen on paper, 26 x 38 inches each poster. Downtown São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist.

BP: It doesn’t help me at all (laughs). Maybe one of the reasons is that, more and more, I feel like I am just the rain that falls. The rain doesn’t choose to fall; it just happens to fall. And its beauty, in part, is this naturalness, which perhaps is the thing closest to truth that we have. So, when I try to release things and not think about them, I am moving towards purposelessness, spontaneity. It’s almost a way of existing in raw form. And this rawness is sincerity. When I stop seeking “solutions” in painting, I can just be who I am, less reactive. I don’t know if that’s good or bad; I just received a call to do what I do.

If you asked Pelé why he played so well, if it was because he loved it or because it brought answers, maybe he would say that he kicked so much because he could kick. The most potent act is the one that happens without a preconceived intention. Painting is, for me, very similar to the act of breathing and even more similar to the fact of being hungry. I just need to paint as I need to eat. Sometimes the food will be great, sometimes horrible. It happened that I had conditions and privileges that brought me to a place where I could be who I am. So that’s it. I don’t have a macro aspiration to be better. I want to be better, but it’s not my purpose.

FM: What is your relationship with the end of existence like?

BP: It’s tough. The only thing I think is that – given the vastness of the planet and all the atomic and chemical arrangements that exist – there is an incredible rarity in being alive, conscious, and operational. So, I am a magical diamond – every human being is. To exist and be aware of it and to think that this consciousness will crumble is a pity. But I can’t even find it wrong because I consider myself luckier than unlucky to exist.

FM: One thing that writing has helped me do is to bring this awareness. You start writing and realize how difficult it is to express things. The “existence” we seek existed long before the current language when we were primitive. I believe that from the moment we settle in a land, we see Time passing differently because we no longer “walk” on Time like the nomads for example. Humans, like all animals, were made to walk. Life only exists in movement, but movement tires and movement eventually wears out. And that’s where I think Time as a language influences us and brings forth our fears. If we didn’t have all this understanding of language, perhaps finitude itself would be different.

Anyway, our relationship with Time has indeed become increasingly complex, and perhaps one of the big problems today is the generated anxiety. You get stuck in the past or the future… and how much anxiety have we already had regarding that future that we don’t even know if it will exist, right?

BP: Although it seems like a very bad thing, perhaps anxiety is the synthesis, the physicality of Time; it is you existing in one moment while projecting another. A synthesis that combines the present with the future based on past experiences. Maybe we are not ready or do not have the cognitive ability for such simultaneous existence, and this incapacity can cause pain. So perhaps anxiety is a way of confirming a limitation. I don’t know where that came from (laughs).

FM: For me, anxiety comes from not knowing if I will be alive or not. But Time is something very personal for each individual. I can say my father left early, but he conducted extensive research and lived intensely for years. We are always trying to parameterize Time for society to function, to have a false sense of control… somehow, this control doesn’t seem natural to me.

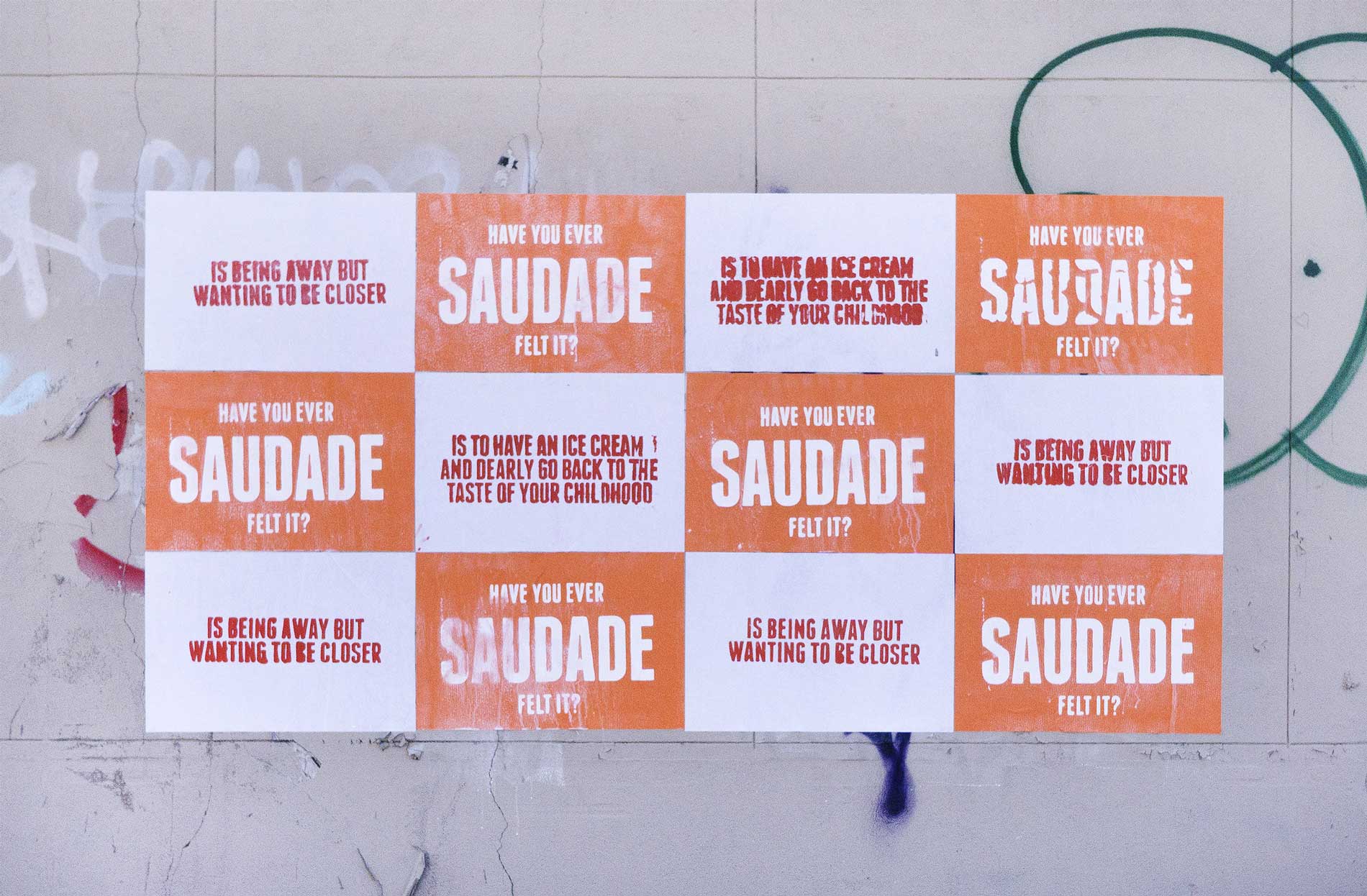

Bruno Passos in his studio, São Paulo. 2023. Photo: Camila Simielli.

Bruno Passos, studio in Jundiaí. 2022. Preparation of the artwork: “Pequeno Assassinato”. Courtesy of the artist.

Bruno Passos and his finished artwork. Courtesy of the artist.

BP: Do you think anyone got anything useful from our conversation?

FM: I think a discussion about Time can go so many places… Maybe in an hour of conversation, we’ve only shown that this word is not limited to four letters and it carries a lot of complexity. We could have tried to talk linearly, limiting ourselves to reach some super objective place, but we had the opportunity to find a more natural synthesis through this exchange of views between art and design.

BP: So after all this talk, if you were to synthesize what Time is for you, what would you say?

FM: That time doesn’t exist. There is a space that makes us feel the need to justify ourselves through Time.

BP: Time is a justification?

FM: I believe that Time is a unit created to organize ourselves as a society. The calendar is a visual representation of Time and serves this function. The clock as well. The eraser is almost antagonistic to Time, presenting the possibility of doing something that is not physically possible concerning Time. I laughed by myself earlier today because I wanted to erase a line that I wrote and remembered that this doesn’t happen in real life, right? What happened, happened. John Baldessari made an eraser with the word “wrong” printed on it. And theoretically, this possibility of time doesn’t exist. It just passes.

BP: Do you think that we could say that Saudade is a poetic eraser?

FM: Saudade is an eraser that doesn’t erase, I think (laughs). And how about for you? What is Time for you?

BP: It’s an attempt at reunion, to bring together a thing, person, or feeling. It’s the desire to glue one piece to another.

FM: Time is glue?

BP: An attempt of glue. A force that seeks to bring things closer. Thinking about the future Time is nothing more than an attempt to glue who I am today with who I will be tomorrow. So, for me, Time is an attempt to integrate, to unify everything. It’s this magical adhesive.

FM: Perfect. Looking ahead, if one day we look back and find this dialogue, how would the future Bruno see what today’s Bruno thinks?

BP: I would tend to think (because I’m pretentious) that I was right and that Time is this glue, this excuse for me to have a direct and deep conversation with someone I like. But, simultaneously, how I will be in the future depends on so many things beyond my control that simply the subject doesn’t interest me. Unfortunately or fortunately, what I have is here, this moment.

FM: What I can tell you is that 15 years ago, I didn’t project being exactly where we are today, but I had a bet on a direction, and that direction was not different from where we are now. So, I still continue to plan, and I am still a hyper-anxious person for it (laughs). I think I’ve been trying to understand Time so that it helps me be more present. I’ve been looking for art to break a bit of my logical pragmatism as a designer and to try to deal better with my own existence. Art has been taking up ample space in me today, but design is of tremendous importance in my life. Because pragmatism was the way I built things in a controlled manner. I will never tell a person to “let it flow” without understanding their moment. If I had let it flow when they told me that, perhaps we wouldn’t be here now. Anxiety, to a certain extent, was significant for me to move to the point of finding a certain security. And that allows me today to let it flow much more than at any other time in my life.

BP: I totally understand. Not thinking at all only comes after overthinking. We talk as if instrumentalized creation were a flaw, but it is what underlies organic creation. It is essential to have a foundation to build the organicity of what you dreamed of initially. As attractive as it is to talk about organic and instrumental creation, it is inseparable for powerful creation to have both things happening simultaneously in different stages. The big deal that might be a different key to all this is understanding time as a reconciliation of moments. If that suffices, perhaps it matters less to us whether the ideal will be better or worse than what we have today, a more harmonious path to accept possible existence.

FM: Thank you, Bruno. I love being by your side. May we meet more in time and also Bruno in space.

BP: I thank you. It’s been a great adventure.

To know more about Fernando Marar: http://fernandomarar.com/ @fernandomarar

To know more about Bruno Passos: @brunopassosbr

Hero image: Bruno Marar, sketch, Camburi, 2023.