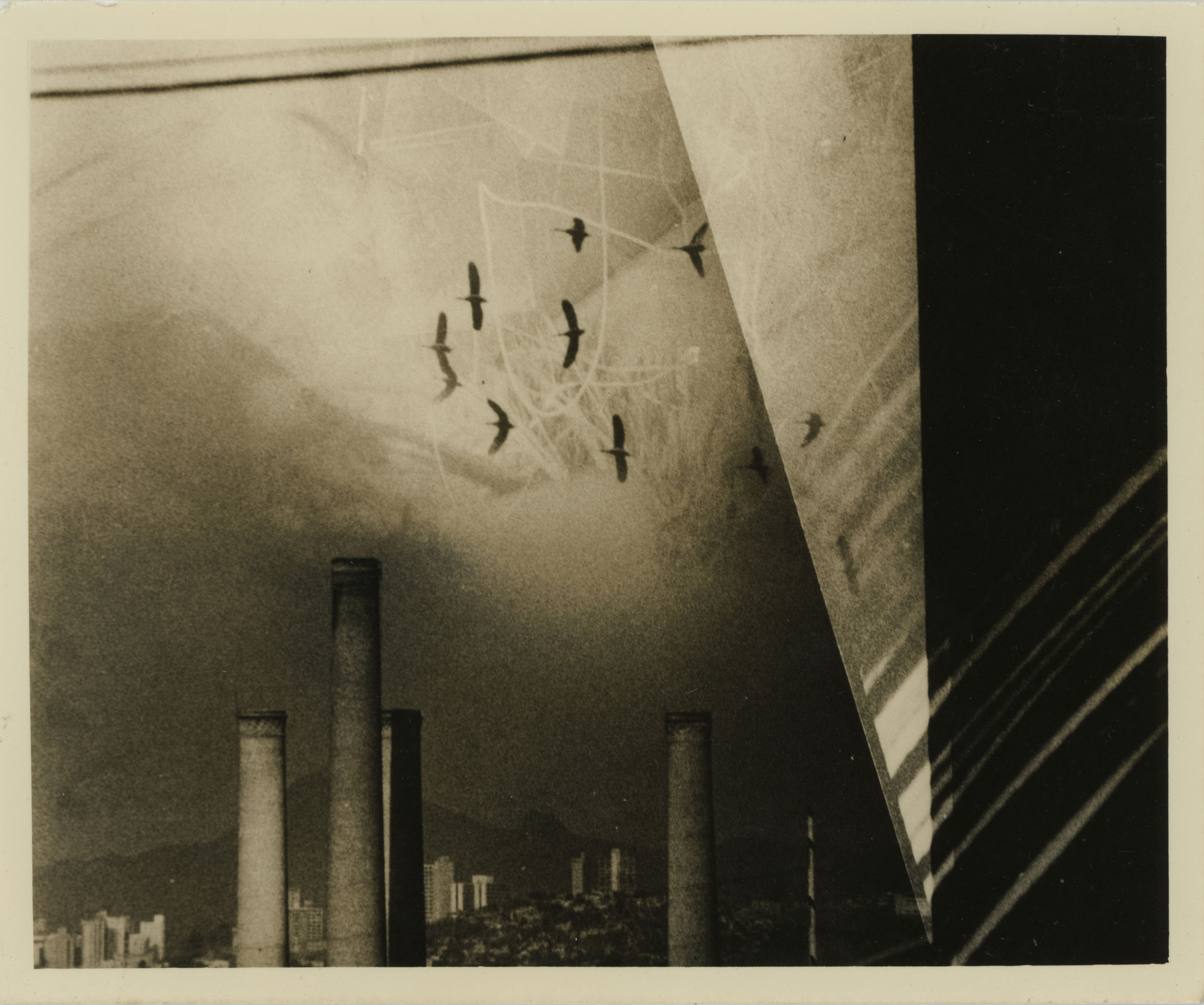

Eustáquio Neves, Arturos series, 1993-95. Mixed Media Photography, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Rodrigo Mitre: Man, it’s such a pleasure to talk to you. It’s an honor to receive this invitation.

Eustáquio Neves: When Anita [Goes] invited me to participate in Art Dialogues, several friends came to mind that I could have a chat with, but then I thought, Rodrigo is such a great guy, and we’ve never really had the chance to have a proper conversation. [laughs] We’ve met a few times, but this is the opportunity for our first real talk, to strengthen these already strong connections. You’re from Minas, right?

RM: I’m from Belo Horizonte.

EN: I grew up there. I’m from Juatuba, which is basically part of Greater BH now, but I moved to Belo Horizonte when I was 11 to live with an aunt and study. Just the other day, I was talking to someone who’s not from there, telling them about my teenage years—going to drink at Maleta and then heading to Bolão at the end of the night. One time, while crossing the Santa Teresa Viaduct, which is actually in the forest, I saw some guys walking on top of the arch, and I wanted to do it too. One of my friends made it across, the other was in the middle of the way. When it was my turn, I froze. I was really frustrated that I couldn’t cross. But now I know a friend of mine who’s an architect—you probably know him, [Fernando] Maculan—has a project to build a bamboo walkway up there.

RM: Wow, that’s awesome!

EN: It’s going to be my chance to finally walk across the arch of the Santa Teresa Viaduct [laughs].

RM: I hope! [laughs] Belo Horizonte is almost an artistic stronghold, right? Especially in the visual arts. I won’t even mention music, because it’s incredible, but for the visual arts, it’s really a hub of resistance, because there are very few truly relevant cultural institutions that promote contemporary art. But the city breathes contemporaneity. And hearing you mention the Santa Teresa Viaduct… it’s in the lower downtown area of Belo Horizonte, and if you go there on a Friday at midnight, you’ll find the Midnight Samba with a queto drum section, which is quite an event. Another thing I love to watch is the incredible young crowd that holds rap battles on Sundays, also under the viaduct. That gives me hope because it’s a super young group discussing contemporary issues, politics, life experience, and the social challenges we face—inequality, racism. And when you see all of that being debated by the youth… Lower downtown Belo Horizonte is a place I often visit for research, to understand what we’re really doing, producing, and what’s truly relevant to present. Seeing this happening in this city gives me hope for the future. It’s a capital city but, at the same time, it’s a bit off the main circuit, especially in the visual arts. There’s an importance to it as a place of experimentation and resistance. I’m really grateful for what the city provides for us. There’s an amazing Black community that is increasingly taking ownership of these public spaces.

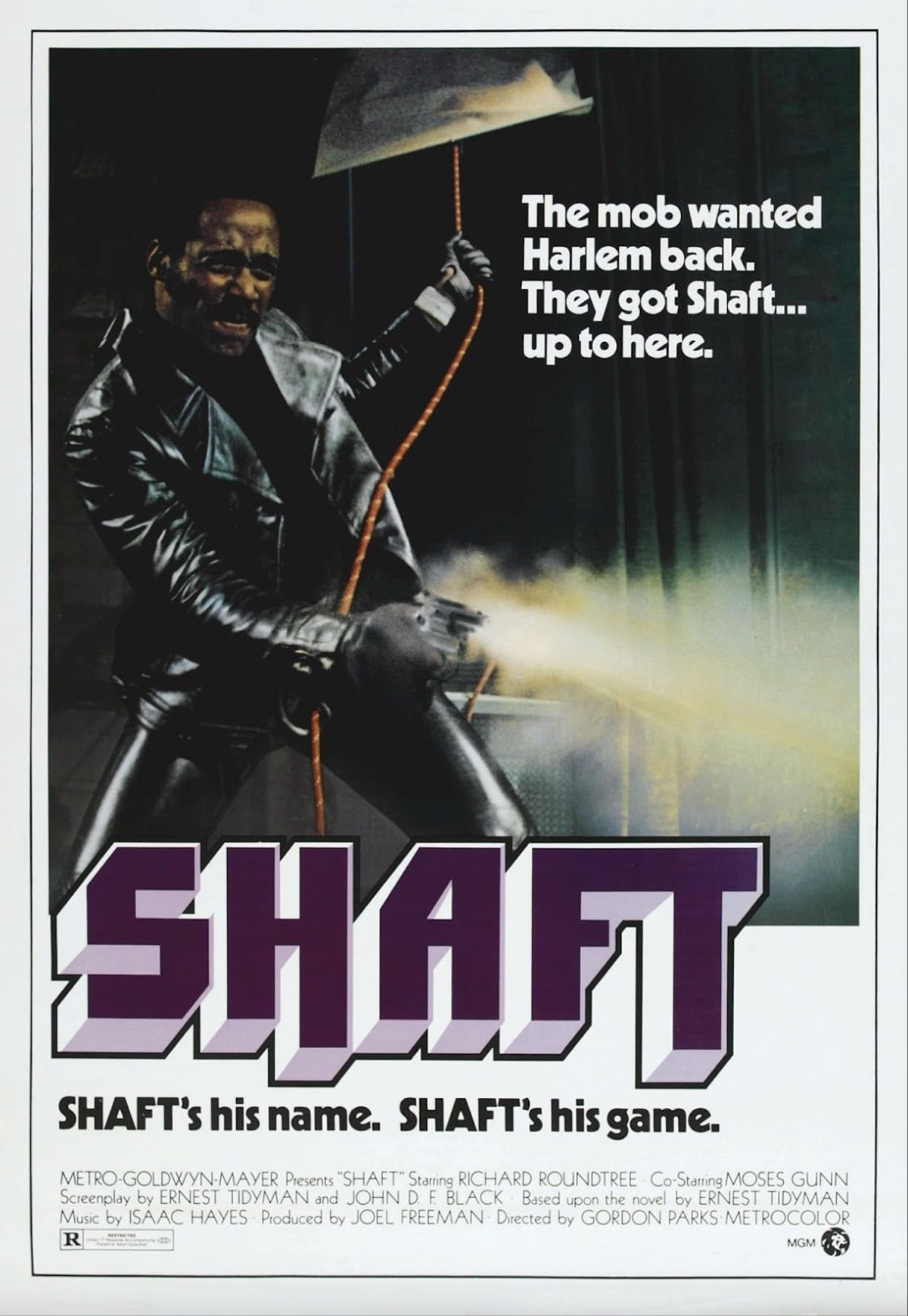

EN: I’m from a different generation, right? I’ve experienced a bit of what you’re living now, but the movements were different. People often ask me about my references in photography. The other day, digging into memories from my teenage years, I remembered that we used to do a lot of things both within and outside the mainstream. When I was about 13 or 14, it would take a few months for an album released in the U.S. to reach Brazil. There was a record store called Pop Rock on Rua Tupis, near the Shopping Cidade mall. After school, we’d go there to listen to the latest black music and rock. I remember when the movie Shaft premiered at a cinema where Shopping Cidade is now; the line wrapped around the block, and I waited in line to see it. Nowadays, I realize that Gordon Parks has been part of my life for a long time, but it was only a few years ago that I discovered him as a great photographer of the Black movement. Anyway, these are the kinds of connections that shape us, even if it takes time for us to realize it.

RM: Absolutely. Since we’re reconnecting and reintroducing ourselves, let me share a bit about my background as well. I come from an evangelical family, and I often say that I’m one of the first attempts of the Affirmative Action (AAP), although not wasn’t exactly the Affirmative Action yet. My mother was a teacher at Colégio Batista. With four children, it was a stroke of luck for us to be scholarship students at that school, and thanks to her, I received a private school education, albeit a strict one. I started working as an office boy at an art gallery in 1996, when I was 19, and I stayed there for almost 12 years. A year after I started, they moved me to a gallery in a shopping mall, Ponteio, which was a project by an architect from Belo Horizonte, Carico, and it looked like a large showcase. On Fridays, there was no one in the mall, and I was completely bored. So, I began to notice that there was a big crowd at the mall every Saturday. Since the store was like a large window set but empty on Fridays, I would take everything apart, dismantle the walls, and set everything up again. It was very intuitive, but little did I know I was starting to work with exhibition design, right? [laughs] So, every Saturday morning, there was a new gallery setup. That early experience was very cool. I had many exchanges with artists. I used to say that my vacations were spent going to São Paulo to visit museums, which was also something intuitive. I think I have a lot of references because of this curiosity I’ve always had.

EN: Amazing!

RM: In the 2000s, a movement started in Belo Horizonte, alongside Inhotim, led by Adriano Pedrosa and Rodrigo Moura to create Bolsa Pampulha. The first generation of Bolsa Pampulha is my generation: Laís Myrrha, Sara Ramo, Cinthia Marcelle. So, I was also lucky to experience this moment of greater attention and professionalization of art in Belo Horizonte, with a new generation emerging and beginning to pave the way in art. Inhotim also played a significant role in that. But this group is now working all over Brazil and the world. When I left that shopping mall in 2003, I took on some production and management responsibilities at Manoel [Macedo]’s gallery, producing exhibitions. In 1994, this was the largest space dedicated to contemporary art in Brazil, and Manoel had a vision of how to house contemporary art. It was very exciting because it was a period when I was very close to artists from the 1970s who had significant visibility in Brazil. Of course, today we see practical issues: many men, many white artists, but they were still very important figures. I produced Artur Barrio, Antonio Manuel, Wanda Pimentel, Anna Maria Maiolino, Sandra Cinto, Tunga, Zé Rezende, and young artists who came from Bolsa Pampulha. It was a time of great learning where I began to understand production, exhibition design, and how to critically bring in a curator or thinker. Alongside that, I took a course in Cultural Management, studied Business Administration, and Foreign Trade. At the end of my Business Administration course, I came up with the initial concept for what is now Mitre Galeria, through an entrepreneurship project that was part of my final thesis. Back then, Amílcar de Castro used to visit Manoel’s gallery every Saturday, chatting and drinking with him. They had this crazy idea of opening a gallery for young artists, and Manoel said he would name the gallery Esperança. So, when I did my project, I named it Galeria Esperança in honor of Amílcar, who had already passed away. I set up an actual gallery within the university, with works and everything, and created a business plan. In 2008, I graduated and left Manoel’s gallery to work in technology, with a partner company from England, but owned by someone from South Africa, called Ubuntu.

EN: Was it in Savassi?

RM: Yes, it was in São Pedro.

EN: I think I might have talked to someone from that company. [laughts]

RM: Really? [laughs] Maybe you spoke with me or my cousin?

EN: I’m not sure. There were people who knew a lot about computers. So, it’s possible I talked to one of you a long time ago.

RM: That’s funny! And Ubuntu comes from this African word that evokes humanity for all, and the company was about open-source software and being a very collaborative, democratic place. That really resonated with me. I think that word also has a lot of meaning in Mitre Galeria today. But I spent five years in that technology field, during the early days of Instagram and social media, which taught me a lot about communication. But I could never completely leave art behind. I was happy because I worked from Monday to Friday, turned off my computer at 5 PM on Friday, and didn’t return until Monday. Once I went back to working with art, that never happened again [laughs].

EN: That’s how it goes.

Eustáquio Neves, Caos Urbano series, 1992 – 95. Mixed Media Photography, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

RM: In 2012, I saw a segment of the São Paulo Biennial at Palácio das Artes that included a video by Rodrigo Braga, where he was in the middle of a forest shouting at a gigantic tree. And I felt like I was shouting to return to that place. That’s when I decided to go back to art, with the project of opening Galeria Esperança, but I ended up returning to work at Manoel’s gallery, taking on the role of director. We started doing some very cool projects, including at SP-Arte with Lorenzato, alongside Adriano Pedrosa and Rodrigo Moura. But in 2015, I opened a gallery, with a strong desire for a fresh start. For five years, the gallery was called Galeria Periscópio, and we did more than 40 projects. Every exhibition had a critical thinker and a photographic record. This was very important because in 2020 I was able to create a book about the five years of Periscópio. And when we began organizing that book, it helped me understand the direction this project was pointing towards, leading us to this new space here in Barro Preto. I don’t know if you’ve been here?

EN: I need to make a visit.

RM: You’re more than welcome! At the end of 2022, I bought out my partners and changed the name to Mitre Galeria. In this new space we’ve done 20 projects in the last four years, including group and solo exhibitions. I think we have this mark of bringing in artists with contemporary research, seeking to understand the moment and what intersects with us. And more and more, this gallery reflects Brazil. It’s not a racially defined gallery, but it does reflect Brazil.

EN: It’s broad, right?

RM: Yes, very diverse, with artists spread all over Brazil. I think now we have a better understanding of our place, participating in international fairs, with many artists circulating globally. Luana Vitra, for example, is one of the artists we’re working with on the Sharjah Biennial project, with Sculpture Center in New York, and Inhotim for next year. Davi Jesus Nascimento just returned from Frieze New York, Marco Siqueira also had an exhibition there last year and now has another at Mendes Wood DM in New York. And there’s a new development, the gallery’s new space in São Paulo, right?

EN: Yes, I saw that in my research.

RM: We found the space; it will be in Jardins. It’s under renovation, and the idea is to have this second gallery space by the end of the year to continue offering new perspectives beyond Belo Horizonte, and also in São Paulo.

EN: That’s great!

RM: We’re in that flow.

EN: I think it’s a flow that keeps growing, right? Like a river receiving its tributaries and expanding. I think it’s like that. And you’ve satisfied a great curiosity I had about your gallery in the Belo Horizonte scene. I come from a time when Belo Horizonte was very segregated, and galleries were for a select few. There wasn’t an interest in knowing who was doing something new or who would bring a new proposal. It was always the same people in the same places. There wasn’t much space for those who were emerging.

RM: And all from the same social class, right?

EN: Yes! Palácio das Artes was a horrible place, a place people didn’t go because it didn’t feel like a place of belonging, you know? Even though it brought many brilliant things, and still does, a large part of the population felt excluded because there wasn’t an inclusive policy there. Inclusive in the sense of encouraging the population and reinforcing that it was a public place. It wasn’t quite like that. It was a public place that offered things to a group of people rather than to the whole population. So, when I see projects like yours, I’m very curious. How does this person manage to break out of that bubble? Because I experienced a lot of that.

RM: There are things about Palácio das Artes that I still don’t understand. I think it’s one of the few places genuinely concerned with promoting contemporary art, right? But there are still things that bother me there. For example, the gate that divides Palácio das Artes from Parque Municipal is always closed, and the fact that the Palácio is closed during the open-air market on Sundays. These are easy issues to resolve, but I think there are some security and technical problems they need to rethink. I’m from here and dealt with a very white, very elitist market, which isn’t my case, for a long time. And I think the artists resist, and this gallery also resists all of that. If I depended on a specific market in Belo Horizonte for this gallery to exist, I wouldn’t be here. It’s a gallery based in Minas, but it’s a Brazilian gallery. I think about 40% of the artists are from Minas, which makes sense considering my background. But we also have artists from the North, Northeast, and Midwest. And the idea is to seek survival and existence a bit outside of Belo Horizonte. So, we end up having a greater presence and penetration in the major axis of the Brazilian contemporary art market, which is São Paulo, and we are also beginning to carve out an international path for the gallery. It’s a movement of resistance, of formation. Belo Horizonte is a very young city compared to Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo. And I also understand that we’re creating this identity of what this city is. An identity that needs to be protected and fostered. Those of us in culture, visual arts, and music must understand that it’s a construction of identity and also how to truthfully tell these stories since we come from a colonialist country where stories were told by the colonizers, by those who were exploiting, and not truly as they should be told. I think we have this role of retelling many stories, right?

EN: That’s our role, without a doubt. And I’m always very pleased when I see people concerned, and not just concerned but actively moving with intelligence, right? We have many questions, but it’s necessary to know how to deal with those questions. It’s not as simple as saying: “Oh, I want to do it!” You can do what you want, but there are boundaries in our surroundings that make things not so straightforward. So, I imagine you must have had to break through some of those barriers to achieve a lot.

RM: If you think about art gallery owners in Brazil, I really am quite an outlier. My identity, right? I look in the mirror and see it. And I’m not an heir. It’s truly a project built with a lot of dedication and a belief in what it can mean for the future as well. I’m already happy with everything we’ve built. But I want it to grow because I think it’s about addressing what intersects with us. For me, in contemporary art, now more than ever, it’s very necessary for us to keep discussing and showing what is intersecting with us. Contemporary for me is today.

EN: And it’s great when you reach that place of reference, I mean, when you are the reference. Because it inspires others to look at it and think: it’s possible!

Luana Vitra, Pulmão de Mina, São Paulo Bienal, 2023. Iron, silver, cooper, indigo ore stone and rope. Photos: Victor Galvão. Courtesy of Mitre Gallery.

Davi de Jesus do Nascimento’s, Furor de Peito e Remela, 2022. Sailing vessel with spills from the series “Gritos de Alerta”.

Mitre Gallery, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Photo: Eduardo Eckenfels . Courtesy of Mitre Gallery.

Marcos Siqueira, Installation view, Mendes Wood DM, New York, 2024. Photo: Dheurle Photography. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM.

RM: I think it’s been possible and is still possible for you, right? Some artists I work with look up to you as a reference, and often their research intersects with what you’ve been building throughout your career. And it’s beautiful to see that this isn’t just about the act itself, but also about much broader issues that encompass our experiences, our ancestry, our beliefs, and how that fosters new productions. I’m very honored to have this conversation because you are a reference for me and many others of my generation and younger generations. We see you as a pioneer. Because since 2015, I’ve been doing something that you’ve been doing for a long time. And building a body of work with coherence, which is truly impressive, in the best sense of the word.

EN: I, like you, don’t know how to live any other way than by doing this. I have awareness, of course, but at the same time it’s very visceral, very important to me. I remember someone wanted to interview me for a newspaper, and I wasn’t really interested in being in the media. I just wanted to be in my corner, doing my work. I said: “Look, I don’t have anything to say.” The person wasn’t too happy and asked what I would do if the doors were closed to me. Well, I know how to cook, I can do a lot of things, handyman stuff. [laughs] But there’s no such thing as doors closing when you truly believe in what you’re doing. You open the doors. They won’t open for you; it doesn’t work like that. But I’m glad to talk with you because I was very curious to know about your journey.

RM: Today I saw the title of a work that I loved. Something like: “It’s not a slave ship, it’s a warrior ship.” So many warriors came here. I have an idea of taking a tour through the gold mines of Ouro Preto, and I was talking about it yesterday. The enslaved people chosen to come here were those who had the skill to find mines in Africa. How this country was built by black hands, right? The strength of labor is a warrior force of black hands in every sense. In iron, mining, agriculture. And it’s crazy how these situations also impact me. I often say that I wake up in a state of war every day. Today, I choose to be in some places and choose not to be in others to protect myself.

EN: I often say that we live at the edge of a frontier every day, you know? Because these frontiers are invisible, and every day you have to cross one in your daily life. We are living this in a way that is… I don’t know if victorious is the right word, but we manage to handle it. When you’re going through customs and then those conversations come up… I’ve even said: “Look, if you want to let me into your country, fine. If not, that’s okay too.” I’ve never had any friction, but I’ve had very serious conversations with them. I was being held up, but the questions, in a way, are pretty silly, actually, right? They take a psychology course and need to ask certain questions. If you’re of color, they have certain questions for you. If you’re Latino, they have other questions for you. I’m not going to answer what they want to hear; I’ll answer what I want to say.

RM: Of course.

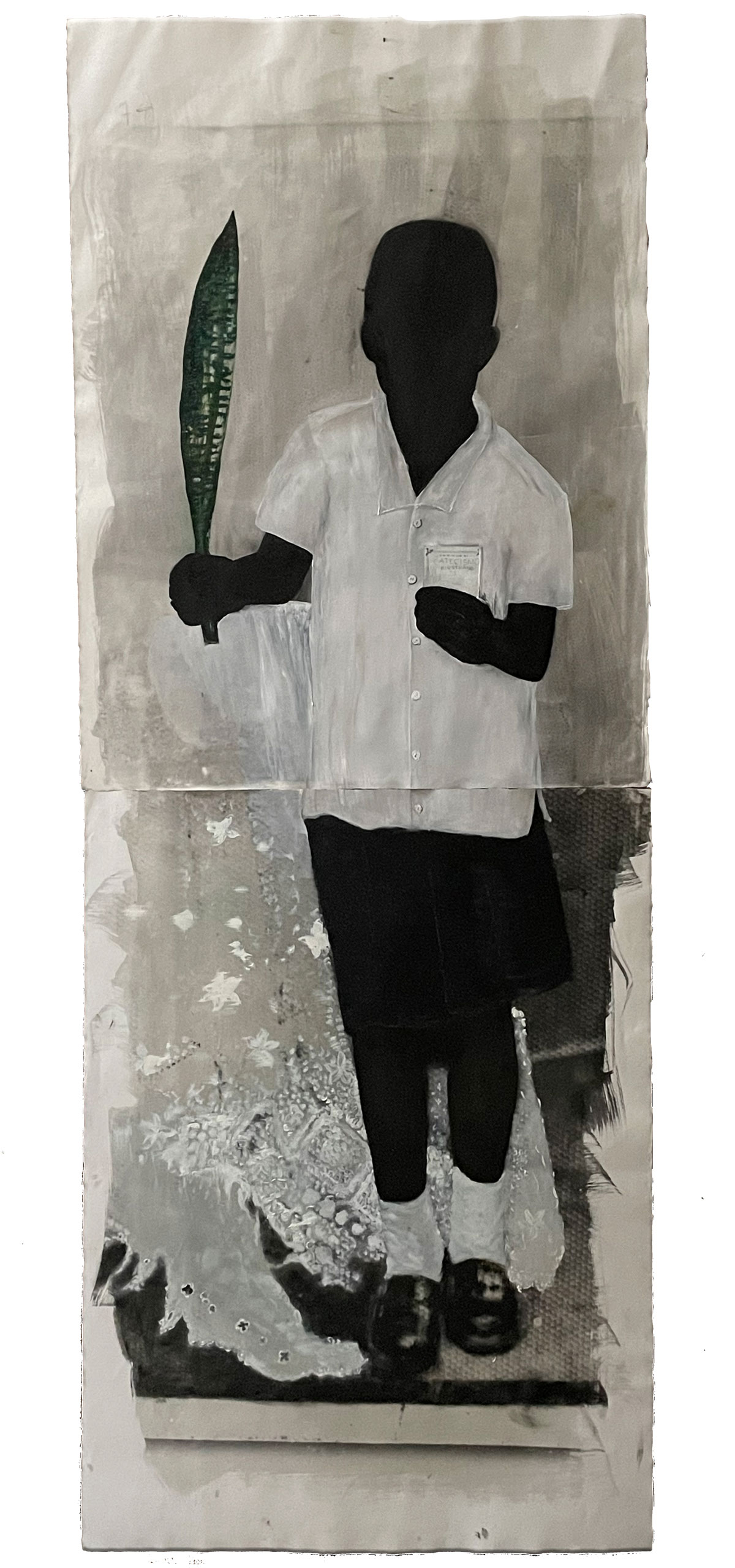

Eustáquio Neves, Crispim: Encomendar de Almas series, 2007. Mixed Media Photography, 12 x 19 inches. Cortesia do artista.

Eustáquio Neves, Arturos series, 1993-95. Mixed Media Photography, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

EN: But in our daily lives here in the art world, which is a field, at first, for the privileged… We are privileged to be in this field, but not because someone allowed us to be here, rather because we belong to this field, we can be part of it. We make it happen because we need what we do. No one is doing us any favors.

RM: I have no doubt. I really liked that phrase and I’m going to start using it: I’m not going to say what they want to hear, but I’ll say what I want to say. And this gallery has a lot of that.

EN: It does! And I’m not going to say what the person wants to hear, you know? I really won’t. I think these are forms of resistance. Attitude is somewhat about having a stance. If I were to talk about stories that have happened to me, we’d be here all afternoon [laughs]. But I’ll tell you one. This was in 1999. There was this prize, the highest cash prize in photography, sponsored by JP Morgan. I don’t know if you’ve heard this story. It was something like: Brazil at the end of the century and the perspective for the new millennium. They invited 25 photographers, and I was one of them. After asking me if I wanted to participate, they sent me the regulations, etc. And there was a person writing about me who wanted to write in the line of ‘this guy is black, he’s broke (financially), always had a messed-up life.’ And I said: “Man, you won’t find these struggles in my life. My struggles are artist’s struggles. If I was broke for a while, it was because I decided to do this. I could be working in something else, making money, because I have a background in chemistry and was working in that field, making money with it. I could just go back to chemistry. But I wanted to do photography.” And, well, I was really low on cash at that time. I had to decide whether to pay rent, buy materials for work, or buy food; I couldn’t split it all. And this prize offered R$1,000 just for participation. And there was also an acquisition of R$5,000. I thought, “Wow, if I win five thousand… I’d have the rest of the year free.”

RM: That’s a big help, right?

EN: And then there was also a grand prize of R$25,000. I didn’t even consider that. But when they sent me the regulations, they simply excluded me because it was the classic thing about image photography, margins, etc. I told them I really wanted to participate, but the regulations excluded me, so it wouldn’t work. I’d lose the R$1,000, but I didn’t want to participate in something that didn’t align with how I think about photography, how I do photography.

RM: Of course!

EN: Then they had a meeting and concluded that I was right and they couldn’t limit these things, and they thanked me for raising the issue. So I did the work. And I did it according to the regulations, with a small margin. I even provoked a bit [laughs]. And I won the R$25,000. I wanted the freedom to do the work and could meet the regulations, but I couldn’t be restricted by them.

RM: I don’t shy away from creating tension when I’m sure of what I want. And although it’s very tiring, because it feels like we’re constantly creating tension, it’s much more rewarding because the results come. If we are very sure of the path we’re on, we have to fight for it, right?

EN: Exactly. And I think, Rodrigo, that it’s not about pushing too hard. I think it’s something else. You don’t even know how to live any other way. I think that’s it. I’m super happy with this chat. And I think it doesn’t end here, right?

RM: No doubts!

EN: I want to visit you there. I hope you visit me here someday.

RM: Definitely. Thank you so much, dear.

EN: Thanks a lot and a big hug.

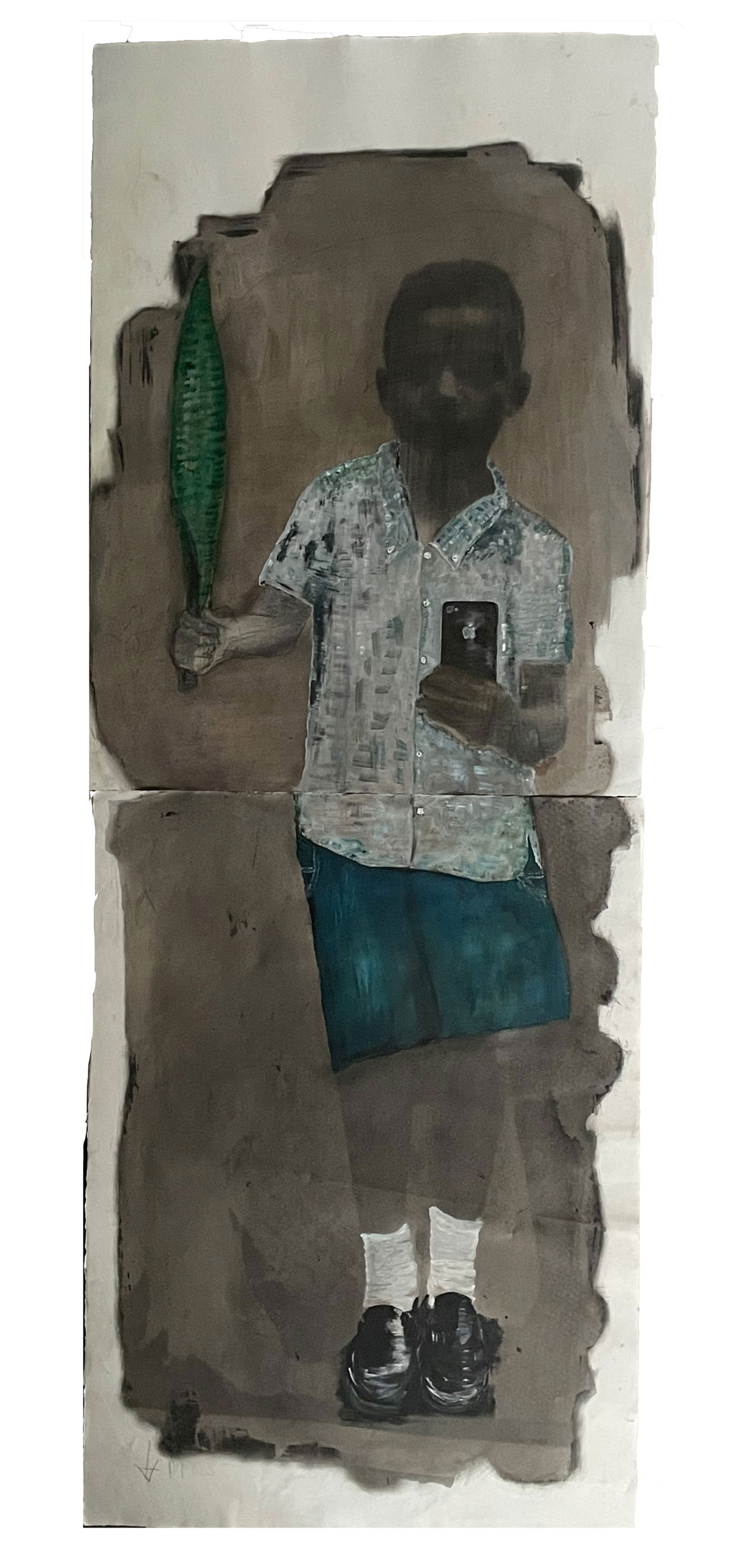

Eustáquio Neves, Seven series, 2023. Mixed Media Photography, 59 x 31.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

To learn more about Eustáquio’s work: @eustaquioseven

Exhibitions:

- 2023: 35th São Paulo Biennial, São Paulo, SP;

- Exhibition Quilombo: Problems and Aspirations of the Black Community, Inhotim, MG;

- Quilombismo, HKW Berlin, Germany;

- Dos Brasis – SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, SP;

- Entre Nós – Ten Years of Zum Fellowship – IMS/SP, Pivô/SP;

- 2022: Solo Exhibition Outros Navios – Photography of Eustáquio Neves – SESC Ipiranga/SP;

- MEDPHOTOFEST 2022 – Catania, Italy;

- 2020: The FotoFest Biennial 2020, Central Exhibition African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other;

- 2019: Aberto pela Aduana – Museu Afro Brasil, São Paulo, SP;

- 2017: Cartas ao Mar – International Discoveries VI, FotoFest, Houston, TX;

- 2016: Arquivo Ex Machine, Itau Cultural, São Paulo, SP;

- Cartas ao Mar – Museu Afro-Brasil, São Paulo, SP;

- 2015: Cartas ao Mar – FotoRio, Rio de Janeiro, RJ;

- 2014: 3rd Bahia Biennial, Salvador, BA;

- 2013: PHOTO ESPAÑA/BRASIL – SESC Consolação, São Paulo, SP;

- III Latin American Photography Forum – São Paulo, SP;

- Afro-Brazil, Brazilian Photography – IFA Galerie, Stuttgart, Germany;

- 2012: Mythologies: Brazilian Contemporary Photography – Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo, Japan.

Mitre Galeria, founded in 2023 by Rodrigo Mitre, emerges with the commitment to contribute to a diverse and effervescent social imaginary in Brazil, and with the firm belief in artistic practice as a key driver to positive transformation of the individual and society. The gallery has been articulating propositions that activate the contemporary arts scene in Minas Gerais, Brazil, and beyond, with a group of artists spanning from different generations, backgrounds and practices. With a program based on aesthetic inventions that shift perspectives, prompting a re-examination of the past and the imagination of the future while anchoring us in the issues of the present, Mitre reaffirms its quest to initiate thought-provoking actions that lead us into the unknown, embracing mystery as a vital force. The year of 2023 consolidates the gallery’s global projection with participation in important fairs and exhibitions. Among them, Marcos Siqueira’s solo exhibition at Frieze in New York, and the prominent presence of artists Luana Vitra in the 35th Biennial of São Paulo and Isa do Rosário in the Liverpool Biennial. In 2024, the gallery plans to open its second venue in São Paulo, while expanding its activities worldwide.

For more information about Mitre Gallery @mitregaleria // mitregaleria.com

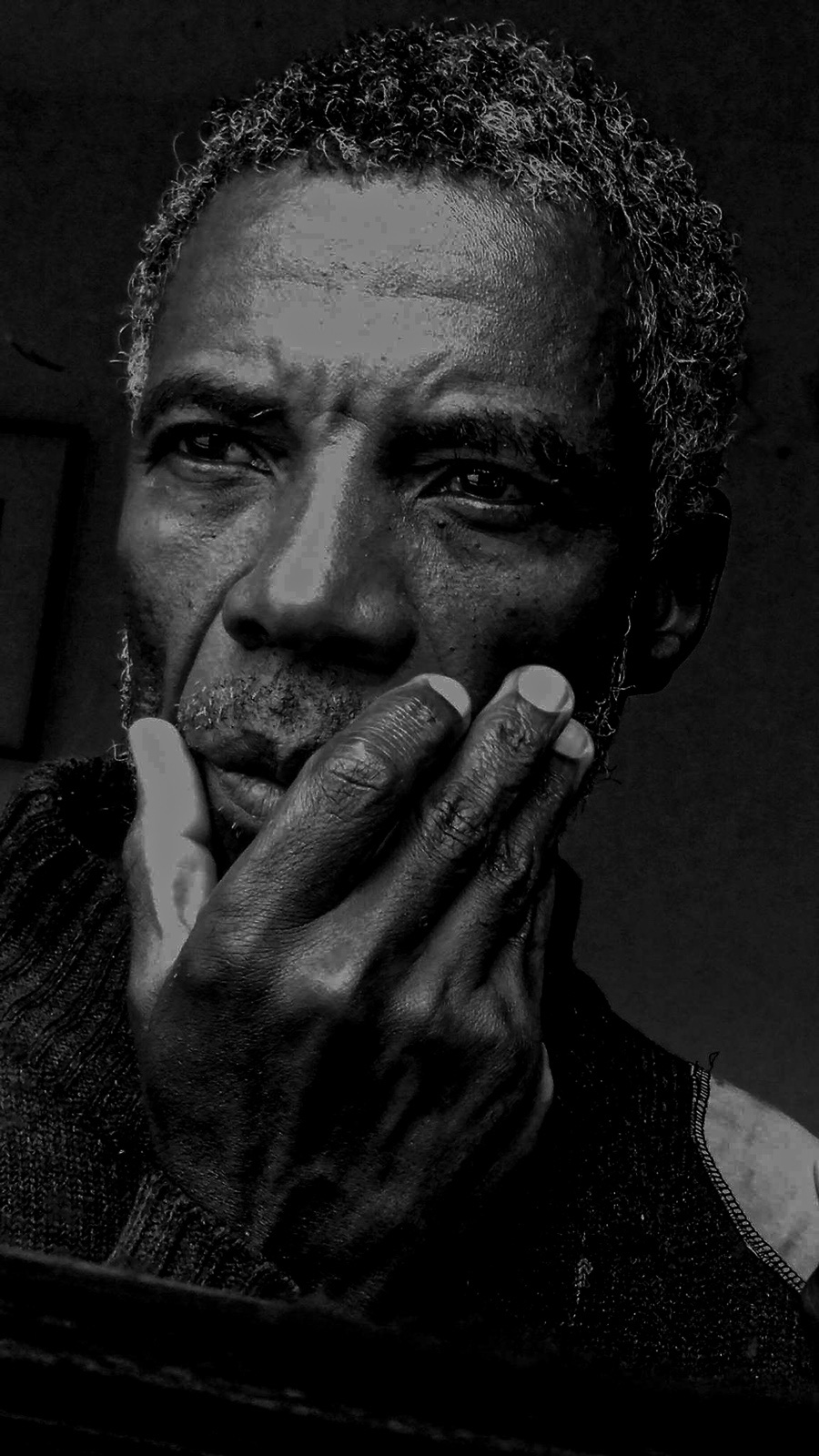

Hero image: Eustáquio Neves, Caos Urbano series, 1992 – 95. Mixed Media Photography, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.