Carlos Junqueira: Carlinhos, we’re already recording! [laughs]

Carlos Motta: I think we can start by talking about how the new chair came to be—its design and concept, right? When you and I first discussed the possibility of this upcoming show at ESPASSO [“Take a Seat,” May 2025 in New York] and the book launch, I felt inspired to create one more piece—something ESPASSO could promote abroad and I could introduce here in Brazil. The Astúrias armchair has already been shown in so many variations—rocking and fixed—but we never explored it with armrests. And it’s funny, because many people have come to the studio over the years asking for an armrest version, and I always dodged it. Until one day, while sketching at home in São Francisco Xavier, I realized I was essentially drawing an Astúrias with arms. And once it gained arms, despite being a large piece, it took on a less outdoor feel—less like a patio piece. It could now live indoors. That opened the door for new materials, new finishes—more refined ones, even shellac. Not that Astúrias isn’t sophisticated, but when you’re designing for outdoor use, you don’t focus much on finish, because it’ll be exposed to the elements anyway.

CJ: And what’s exciting is that we’re putting together something ESPASSO has probably never done on this scale before: a show with ten of your seats. All of them are featured in the new book [Carlos Motta, Ubu Editora], which is incredibly inspiring and proves your work goes far beyond the Astúrias. That was the angle I found to frame this exhibition: to show that Carlos Motta is all about chairs. No one does chairs better than you.

CM: And that really is the story of the studio. I’m here right now, and honestly, it’s just a sea of chairs and armchairs [laughs].

CJ: I remember your frustrations. Even though I sometimes challenged them—and yeah, sometimes we’d clash a bit [laughs]—I understood. For a long time, there was this tension: who is Carlos Motta, the designer? And who is the Carlos Motta that ESPASSO, as a store, presents as a product designer? And now, I feel fulfilled because we’re doing a show that finally reveals who you truly are as a designer, in your full breadth.

CM: I think it’s wonderful that we’ve reached this point together. It was never really a fight—it was always about the sum of our parts, what we create together. We’ve had great success, especially in the outdoor space, centered around the Astúrias fixed and rocking chairs. They’ve become best-sellers everywhere—in the U.S., in Brazil. Actually, when I look at my company’s revenue, half of it comes from abroad. We’re doing major projects in places like Dubai, the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica. People have really embraced my furniture—they understood my design language and took it elsewhere.

Now, after more than twenty years, ESPASSO is giving us the chance to widen the lens—go beyond Astúrias, beyond outdoor pieces—and show this entire spectrum of work that already sells incredibly well in so many places. There’s a demand, and I never stop designing new pieces. These works are entering the orbit of architects—friends like Tiago Bernardo, Isay [Weinfeld], Marcio Kogan, who, by the way, lived next door to me when I was five—and others they know, including international names. But my key representative outside Brazil is you—it’s ESPASSO. And now we have this opportunity to truly showcase the full range of my work abroad, alongside a book. This exhibition is our joint project, blending cultural vision and commercial reach.

CJ: Absolutely! And how long have you been working now? Nearly 50 years?

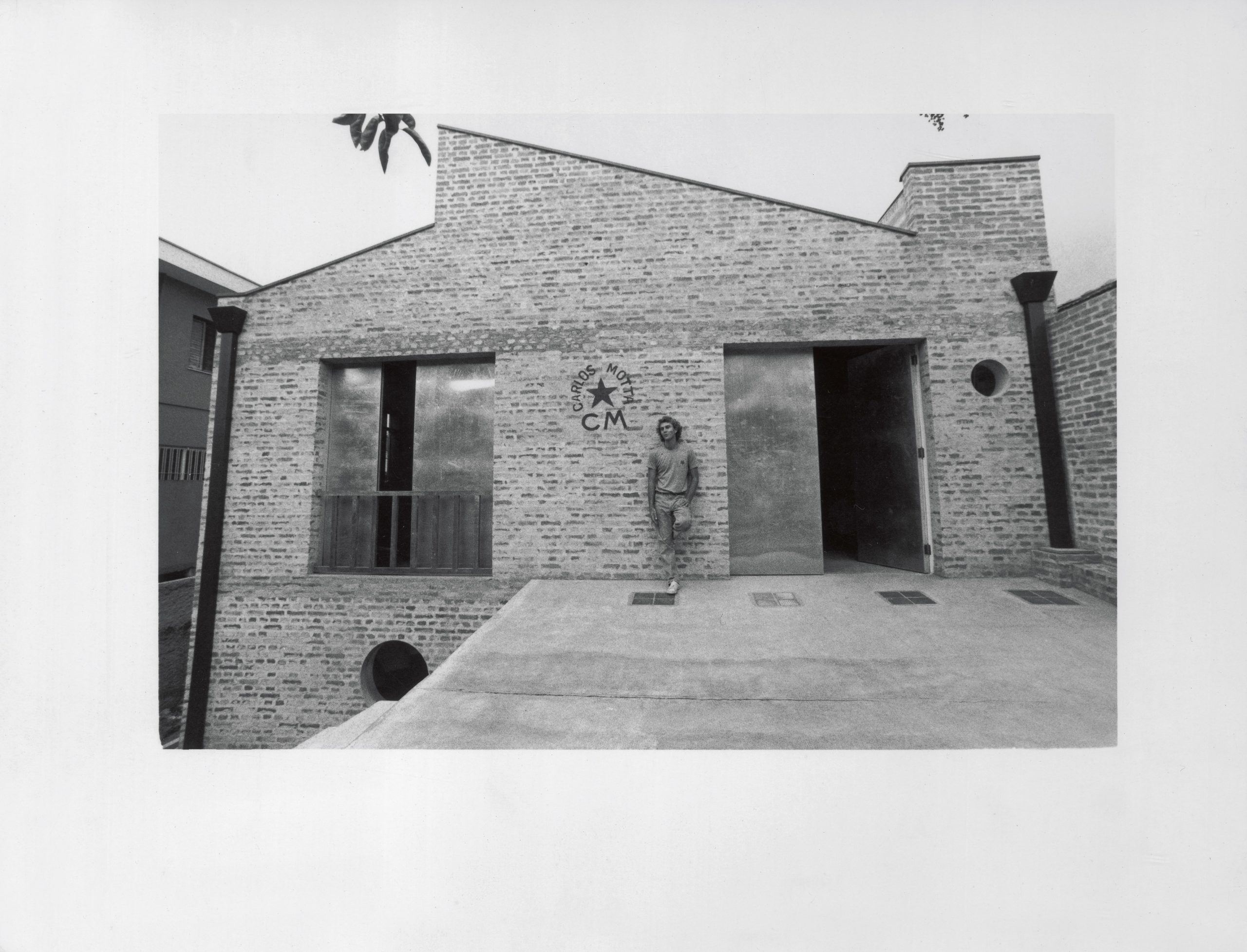

CM: Just about. The studio has been running since 1978.

Carlos Motta in front of the newly inaugurated Atelier Carlos Motta, 1978. Vila Madela neighborhood – São Paulo, Brazil. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

Left image: Carlos Motta, Asturias Lounge Chair, 2001. Right Image: Carlos Motta, Asturias Rocking Armchair, 2001. Courtesy of ESPASSO.

CJ: And in the beginning, it was just you, right? I remember clearly how I’d often share my own struggles with you—not just in easy conversations but in some with a little friction too [laughs]. I didn’t have the space, nor the resources, to put on a show for you—everything had to be small. Today, I want to work in a way where all ESPASSO locations are fully connected. Which means your launch will happen simultaneously in LA and Miami.

CM: That’s amazing, Carlos. It shows the maturity of your work and our partnership. I like to think of you as the trailblazer for Brazilian design—you started out on the fourth floor of a building in Queens. It was a timely move [in 2002], but it also took a lot of dedication, risk, and faith in something that had slim chances of working.

I remember once, when I had an exhibition in London, I told my father—who was always very ironic—and he said, “Oh, great. But you’ll see—tomorrow they’ll turn the page and there’ll be a show from Afghanistan. The next day, Scandinavia. You’re just one more.” That hit hard. I was furious. I went to London, did the show, and sure enough—next day, they turned the page, and there it was, a show from Scandinavia. But you—you never saw it that way. You took ownership of the page.

It must’ve been incredibly hard—commercially, financially, and logistically. Brazil was completely unprepared to export furniture responsibly—whether we’re talking about the origin of the wood, the packaging, or the paperwork. It was all incredibly difficult. I thought for sure you’d give up and take that heavy backpack off your shoulders. But you didn’t. The showroom went from Queens to Manhattan in no time, and then to LA, Miami, London. You carried the weight of exporting and consolidating Brazilian design on your back.

CJ: Meanwhile, the Campana brothers—who had nothing to do with ESPASSO—were blowing up, especially in Europe.

CM: They were the two spearheads, really—ESPASSO, with all its pilgrimages, and the Campanas, with their highly conceptual work that achieved massive visibility. Today, ESPASSO is known worldwide as the representative of Brazilian design. And when I think back to those days in Queens, it’s surreal… us eating cold slices of pizza on the corner, you rushing back upstairs to fix the gallery floor. Look where we are now.

ESPASSO’s showroom in Long Island City (Queens), New York, 2002.

Carlos Junqueira (left) and Carlos Motta (right) in front of ESPASSO New York during Motta’s exhibition in 2018. Courtesy of ESPASSO.

CJ: Now, Carlinhos, I’ll tell you… the work got to be so much that there came a point where it became exhausting and started to lose the essence of how it was built. For me, it eventually started losing its identity, and now I’ve come back in such an intense way that they’re calling me, what is it again? A micromanager [laughs]?

CM: Obsession Micro Management.

CJ: That’s it. And it’s not that I want to control everything, but I do want the core, the essence of ESPASSO to be expressed the right way.

CM: If you had to define it… What is the essence of ESPASSO that you’re referring to?

CJ: When we started, we had everything—rugs, bowls, furniture, everything. Since I didn’t know what the financial outcome would be or how I’d survive, I put everything in there. If a piece of furniture didn’t sell, maybe a bowl would. If not a bowl, then a lamp. And that started fading because the company started getting big. But it can be a big company and still keep the original concepts. And now I have this wonderful team by my side, which didn’t exist when I started. Back then, people didn’t really know who Sergio Rodrigues or Joaquim Tenreiro were, but there was a lot of press about ESPASSO because there was nothing like it anywhere else in the world. It’s a mix of culture, a mix of people, a mix of struggles, of richness, you know? And that’s how ESPASSO grew—and now I fight for it.

Carlos Motta, Muirá Bowl, 2019. Courtesy of ESPASSO.

Carlos Motta, Koguma Floor Lighting, 2015. Courtesy of ESPASSO.

CM: That’s powerful—because you’re not just communicating a product, or a functional object. You’re telling the story of Brazilian design. From the start, when you came to me about representing Brazilian furniture abroad, we both knew that showing just one designer wouldn’t work. You committed to presenting the identity of Brazilian design through the work of many. And that identity—what makes it different from Italian, Scandinavian, or Japanese design? It’s in our habits, our materials, our relationship with life, nature, labor. I remember when you sent Ruy Teixeira to photograph my home in São Francisco Xavier, to show how I live surrounded by the forest and water. And when I’m not there, I’m at the beach, surfing, fishing. This way of living outdoors—the way Brazilians engage with nature—it all shapes our products, our architecture, and how we live. So maybe someone in New York, seeing an Astúrias chair or another of my designs, will understand it better through those images, through that context.

CJ: That’s exactly it—and few people know that you’re also an architect. Furniture lives in the home. You have to show the home to tell the whole story.

CM: Totally. It’s about clearly situating where Brazilian design stands. I spent some time in Scandinavia studying their furniture—it was interesting and culturally enriching—but I came back struck by the coldness of it all. It felt very distant from the way I live and what I value. What matters to me doesn’t necessarily matter to them, and vice versa. So our everyday lives deeply inform the objects we live with. When you visit an Indigenous village in the Amazon, for example, life is rustic, and they have very few objects—but each one is deeply intelligent, made specifically for how they live.

CJ: Exactly. It’s about the context, the perspective, and the way we interpret things—and the materials we have access to.

CM: Our woods are incredible. Each type has unique characteristics and is good for different things. I’ve always loved researching that. The stress points in furniture—especially chairs—demand specific properties. I choose woods based on what I want the piece to achieve. And I almost always use reclaimed wood—90% of what I make uses wood that’s already had a life. Cutting down a tree is something that hurts. And beyond that, I believe the entire team involved in production should share in the profits. Otherwise, we end up with this madness of Elon Musk types hoarding wealth, sending money to Mars. That’s not it. What matters is cultural participation, financial participation, being part of the joys and the hard times. We should shorten the workday, work less but more efficiently. That, to me, directly shapes the quality of design and architecture—because that’s humanizing labor. And that’s a pillar for me. The drawing, the social and environmental responsibility—that’s what I believe forms the modernity of Brazilian design.

Carlos Motta, Flexa Stool (tall and short. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

Carlos Motta, Saquarema Rotating Lounge Armchair, 2005. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

CJ: That’s great, Carlinhos. Another point I wanted to bring up—something closely tied to the work I’m doing—is getting Brazilian design into museums. We’ve already started with the Mole armchair [by Sérgio Rodrigues], and I plan to keep going. So tell me, which chair would you like to see in a museum?

CM: I’m heading to Portugal tomorrow, and I’ll be passing through Lisbon to visit the Design Museum there—they have an Astúrias armchair on display. It’s an old museum, a beautiful space, and every time I see that chair there, it really moves me. I think the topic of museums is super important, but there needs to be a clear context—design today has to reflect environmental and social responsibility. Otherwise, it feels totally disconnected and, to me, has very little meaning. It’s no use admiring a gorgeous Prada bag if it was made under near-slave labor conditions. Or a piece that uses materials extracted in a horrible, destructive way—ignoring environmental and social issues—and then sells for thousands of dollars on Fifth Avenue. That’s just completely wrong.

CJ: Absolutely. And you’re right—there are design pieces already in museums that probably wouldn’t pass that test today. But look, your seat collection, for example—it invites people to understand the very context you’re talking about. Through photos, objects, materials, books—all of it speaks to the identity of Carlos Motta, the designer. They reflect different periods, different processes, and different emotions you went through.

CM: Exactly. But they’re all connected by the same thread.

CJ: The chair is a part of the designer’s essence. A successful chair encapsulates thought, energy, timing, struggle, and emotion—it’s much more than just an object.

Carlos Motta, Java Lounge Chair, 2014. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

Carlos Motta and Mestre Toninho, Woodworking Shop Vila Madalena (Aspicuelta Street), Brazil. Photo: Paula Brandão. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

Carlos Motta, Maresias Armchair (canvas), 2016. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

CM: Carlos, it would be cool to have some of Ruy’s photos in the exhibition, right? Some shots of the architecture, the forest, the furniture.

CJ: Yes, I think that would be amazing. Let’s present this in a way where people leave with both understanding and questions.

CM: Maybe we could even print them lambe-lambe style—with high-quality printing on more modest paper.

CJ: That’d be super cool. We haven’t even gotten into that yet. Right now, we’re opening the Carmel Armchair exhibition by Sérgio Rodrigues—three chairs that are completely identical, except they’re spaced ten years apart. But let’s definitely come back to your idea. When do you return from Portugal? Do you have good photos of the Astúrias in the museum?

CM: I’ll be back on the 26th or 27th. Not sure if I have any, but I can take some if needed. Remember that beautiful photo of the Astúrias in Alicia Keys’s home? It’s a stunning shot—though I’m not sure if we’d be allowed to use it.

CJ: You know what we never did? The round Astúrias sofa. Damn it.

CM: That’s Paul McCartney’s sofa! I have a photo of it in the workshop—another beautiful image.

CJ: Let’s look into all of this then. I’ll let you go since I know you have a meeting. Big hug! Let’s stay in touch.

CM: Thanks, Carlos!

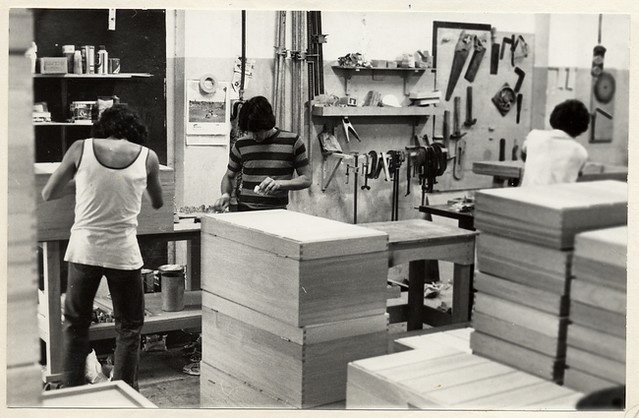

Left image: Toninho, Zeco, and Béu, circa 1970, at the Purpurina Street Woodworking Shop, Vila Madalena, Brazil. Right image: Carlos Motta in front of his Woodworking Shop, 2010. São Francisco Xavier, Brazil. Photo: Fernando Laszlo. Courtesy of Atelier Carlos Motta.

Carlos Motta, Marajó Stool, 2019. Courtesy of ESPASSO.

To learn more about ESPASSO: @espasso // www.espasso.com

To know more about Carlos Motta: @ateliercarlosmotta_oficial // www.carlosmotta.com.br