Bruno Baptistelli: I noticed you purchased Neusa Santos Souza’s book. This week I’ve been meaning to express my appreciation for what you do. You stimulate intellect. Indeed, that’s your profession, isn’t it? I find it very interesting because… well, now it’s also an atypical situation being a father. It’s rush and changes in life. Mine, Carol’s, and Rosa’s.

I was discussing with Carol, reflecting on the pandemic. It was a period when I read a lot, and coincidentally now I’m writing a text for a museum in the United States, which is the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s an important museum there, and it has been good, a new experience.

You often distill your ideas into written form, don’t you? Like the text you crafted for my solo exhibition at Galeria Luisa Strina, where you engaged with the exhibition remotely through documentation: photos and videos, even though you couldn’t visit in person. And well, you’ve been following my work for quite some time, and since the bebaprafrente, you’re aware of the significance we attributed to recording back then.

I’ve continued to pay attention to this recording practice. Because I see art a lot like that: a record of my passage on Earth. I think I may have already told you that I always thought my madness was a bit like: “Wow, what if the world ends, humanity ends, and a new civilization finds an object that I produced and that is not in the order of the utilitarian.” Similarly to how you might pick up an object and remark – “Oh, okay, this was a mug. This is how people in that ancient civilization drank liquids or, perhaps, consumed solids”. There’s this whole concept of the tool, right? But what about objects that aren’t utilitarian? Anyway, more thoughts came to mind as I was speaking, actually.

Vinicius Costa: Aham.

BB: But what interests me a lot is us, our conversations. Another thing that came to mind: this week, I was at a dinner at a friend and collector’s house, and there was an artist present. An artist who already knows Carol, my wife, for a while. She asked about Carol, I replied that she’s fine. Then she asked about Rosa (Bruno’s daughter) and I realized that initially, I almost didn’t turn the screen to her. Because, in fact, I wanted to revisit that moment when Rosa is starting to walk, babbling things, you know? And I think I said something about language. Coincidentally, this collector has the work Linguagem that you know: NEGRO, PRETO.

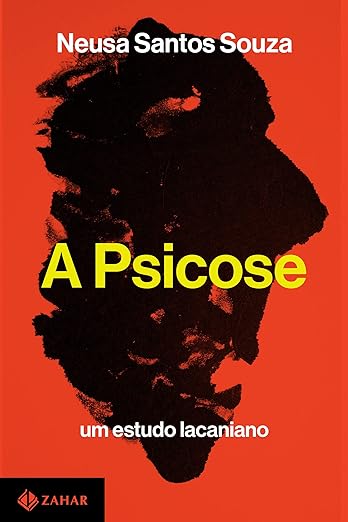

This text for the Art Institute of Chicago delves a bit into that. I also bring up other questions. I don’t know if it will come up in the conversation, but she asked if I had read about the notion of the mirror in Lacan, and if I had read Lacan. I said, “Well, I haven’t read it, but I have a great friend who is a Lacan scholar.” So she began discussing language, and it got me thinking that perhaps I’d like to know more about this aspect of language. I’m curious about your perspective on language or Lacan and how it has influenced your work. After all, you’ve been studying this for about fifteen years, if not more.

VC: I entered college with a strong curiosity about Freud, despite not having delved deeply into his work. At that time, I was unaware of the nuances and distinctions within psychology; to me, psychology equated to Freud. During that period, I discovered phenomenology, behaviorism… It’s interesting. I had my moment of liking Freud. I rejected Freud for two years. It was with Lacan that I regained interest in Freud. And today, I see Freud from a different perspective.

BB: And when did this happen?

VC: I went to Argentina determined to study Lacan in 2008-2009. So that’s about fifteen years ago now.

BB: Did you go to Argentina because of Lacan? Because I often joke that I’ve always been a traveler driven by love, don’t I? (laughs) That’s how I left the country for the first time.

VC: (laughs) Sometimes a bit of hatred too, right? But it’s part of it. (laughs) There are days when love and hate are very close like that. But yeah, I think I have this thing. You’re a witness, right? There’s this very constant presence of psychoanalysis in my life. Increasingly, I find myself inclined to view psychoanalysis as a form of politics too. Not just in the consulting room but also frequently in conversations with people I’ve just met, or even between the two of us in a bar (laughs). They ask me: “but aren’t you tired? Do you want to talk about work”?

BB: It was supposed to be a moment of relaxation (laughs).

VC: Exactly (laughs). It’s different from counseling someone. While counseling is indeed work, for me, integrating the unconscious into political discourse represents another realm entirely, in the sense of…

BB: Existing in everyday life.

VC: Exactly. I believe we’re still a long way from developing a politics that can truly integrate the unconscious. And it’s precisely related to this thing about the mirror that your friend brings up, in the sense that we…

BB: Sorry, I am interrupting you so I can try to see the mirror. “To include the unconscious in day-to-day life”. You say in… can I say in the conscious?

VC: In everyday life. In fact, that’s where the unconscious comes from for Freud. There’s a very striking text of his called Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), where he talks about the formations of the unconscious. There are two very remarkable things in Freud: the first is language. He goes from an issue of hereditary transmission to a transmission of law. And this law is not made without language. Maybe this is the first point to talk about language. There is a relationship between language and law. Not the legal, moral law of right or wrong. But also, it’s not without this that this law is made. It’s a law of language. Lacan will talk about the law of language, in the sense that there is a way for you to be constituted by language, from which you carry a law, right? So, this law, it is placed in the subject in an alienating way.

BB: Got it.

VC: And this alienation can only occur through the mediation of another, leading us into the realm of the ‘small other,’ as Lacan distinguishes it from the ‘Big Other.’Each thing I’m talking about here could be explored in much more detail. (laughs)

BB: But a summary…(laughs)

VC: Let’s start here to see where this conversation takes us! (laughs)

Bruno Baptistelli, Linguagem, 2015 – Offset print on paper mounted on wooden chassis, diptych. 16 x 23 inches each each. Photo: Gui Gomes.

BB: I acknowledge some of the points you’re referencing. However, with each moment you speak and as we discuss it further, it opens up new interpretations for me. That’s why I like our conversations so much, and that’s why I mentioned you, going back to that artist who spoke about Lacan, and that’s also why when I received Anita’s (Goes) invitation to participate in the magazine, I thought of you. I think these are the conversations that interest me the most in life. Not just today. We’ve had an exchange for many years, but it’s always very enriching to talk to you. And also because you have this approach in your speech that I find myself closely aligned with. We’ll see how this conversation plays out, what will be transcribed, and how it will resonate in the world (laughs).

Stepping back a bit, you’re delving into specific topics, which I appreciate. And it seems like there’s a wealth of conversations to explore within this conceptual field you’re engaged in. But please, continue. You were saying…

VC: This very proximity between us is itself an example of the mirror. There’s something here that may have been operating unconsciously for years, and that we identify with. Things that I can attribute to Bruno, his relationship with the arts. On one hand, you also enrich my understanding of art. It’s a field I lightly flirted with, grazed, you could say. Very distant compared to you and the artists who have been in it for a while, but it still interests me. Mainly because of the question of the object. I’ve told you about this. The artist’s relationship with their object, the artist’s series, for me, has something very close to psychoanalysis, even closer than many schools of psychology, like the ones I mentioned when I entered college. But I was talking about the ‘small other’ and the ‘Big Other’ to touch on the issue of the mirror and the fact that when we learn to speak and acquire language, this doesn’t happen without a ‘small other’. It’s nothing more than any other who is close to me. Those who are close to me, most often maternal and paternal figures, or those who assume these functions. They will transmit, through language, their gestures; it’s truly a mirror. The idea of the mirror, the Lacanian hypothesis, and what we witness in the clinic and in psychoses – referring to Neusa Santos Souza’s book – is that first, the self is another. First, for the child, it aligns itself with the image of the other, and as it aligns itself with this image, with this person on whom it depends viscerally, vitally, for food, for warmth, and from whom it cannot yet equate language. In this impossibility of corresponding through language, the child babbles, it cries. While calibrating its language to the other, it has already inscribed itself in a specular field. Unconsciously, along with language, it also acquires the gestures, the forms of the person… on whom it depended for survival.

BB: They’ve already become alienated.

VC: That’s it, already alienated. So, for psychoanalysis, the self is another. The self is an object that operates from a subject of the unconscious. The self and the subject are two elements, let’s say, of Lacanian psychoanalytic grammar that do not coincide. The self is much more the individual.

BB: Uhm.

VC: …which literally, ‘individual’ is someone who is not divided. The subject, it will divide itself. And the mirror stage helps us think about one of the ways to talk about this divided subject, we could go through many aspects. One of them is also thinking about the subject as that which separates me from you. But at the same time, I approach you to obtain a kind of recognition. Who would I be and what would my ideas be without anyone to hear me? This creates a sort of attraction toward you. But my unconscious, unrecognized, instinctual need, drives me away. So, this subject of the unconscious operates in between. That’s why I jokingly said: “Lots of love and hate”. Because everything we dedicate ourselves to and put our guts into, ends up turning into hatred. It’s intertwined. We see these ambivalences happening in sessions, and we try to operate precisely on this ambivalence. I think, could the dissatisfaction of an artist with their last work be something like this? I don’t know. I dare say that every artist wants to produce the next work; it’s always there, wanting the next, the next, the next. And that’s where I think we can consider a politics of the unconscious in the sense that capitalism appropriates this. Capitalism appropriates in the sense that the last one is not the one you want; it’s dissatisfied. You need more! You need more, more, more. Capitalism doesn’t invent this; it appropriates this way of using this instinctual condition…

BB: human.

VC: Yes, human condition pushing for…

BB: as a form of profit.

VC: …pushing products. One more, one more, one more… That’s why the serious artist is the one who takes into account the series. They will know the value between one work and another. They will return to themselves. Or else, they will not become just the promise of the next product. But all of this ends up happening because there’s a logic that belongs to no one…

BB: You said, “takes into account the series.” Are you calling this work over time a series?

VC: Yes, work over time.

BB: Got it! Not a series, like this work is an edition, it’s a series. I understand.

Bruno Baptistelli – Views of the exhibition ‘For a While’ – Artkartell projectspace, 2017. Photos: Sári Ember.

VC: Therefore, just like the works of an intellectual or a writer, just like a child’s drawing, there is language. Just for us to start anew. The mirror has a bit of that. And language is the way I will alienate the other as well. They will be able to speak about themselves in a language that is not their own. And only in this way can they, in a language that initially does not belong to them. We talk a lot about structural racism, for example. This is an awakening to this place of the ‘(Big) Other’.

BB: Yes, yes!

VC: This has a politics of the unconscious, I think.

BB: Ah, I see.

VC: The structural is the unconscious!

BB: Yes, absolutely

I also discuss with you how I find the role of psychoanalysis important for real changes in the world. Whether in an objective or subjective sense, the moment when we get to know each other or get closer, we never define the initial meeting moment. We recall a gathering on the rooftop, perhaps a party thrown by someone from the college you attended, and…

VC: You helped me think that the arts need a package insert. I never forget that, the day when you talked to me about ‘art with a prescription.’

BB: I think you brought that…

VC: That was my criticism at the time. It’s interesting how you change my perspective, you change my mirror for art. Because initially, I used to say, ‘If it needs to have this text, it’s not art.’ I thought art had to be something that impacts! No labels explaining it. That’s what I believed back then; we can say it was something in which I alienated myself.

BB: Yes, that activates others, that makes…

VC: That makes the person arrive at a place. But you gave me a notion of art that is already included, right? So, at first, I have a synthesis of what I am. I meet you, who breaks my mirror. The mirror has to be broken; that’s the idea in psychoanalysis, the mirror is meant to be constantly broken. We suffer from solid mirrors. Mirrors that are very crystalline, very clear, very transparent, are a problem. Because our energy, and I’m talking about instinctual energy, needs to destroy something.

BB: Yes.

VC: To destroy itself. And I think a good culture is one that provides possibilities for us to destroy ourselves symbolically.

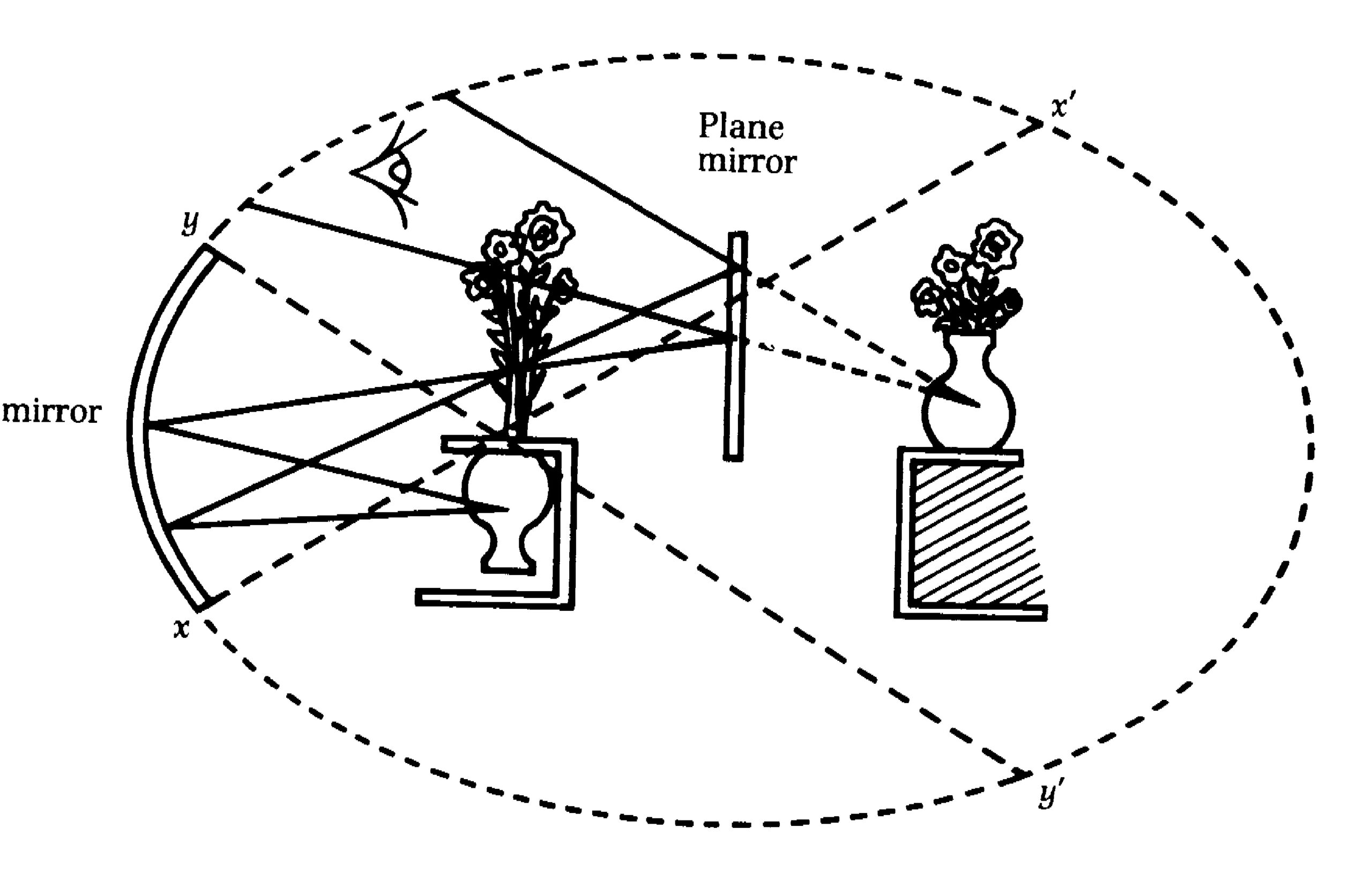

BB: Interesting, you said crystalline, clear, which is a place I’ve been thinking about. And one of the works featured in this exhibition, for which you wrote the text, was titled, or rather, is titled, because the work exists, not in the exhibition, but continues in the world. It’s called Linguagem Escura. I’ve been interested in this place that comes from some readings about Glissant’s concept of opacity. But I was also going to talk about our meeting. Why was I going to talk about that?

Lacan Optical model – Mirror

Oh, because it’s also at that moment that I start to hear about subjectivity. You’re talking about consciousness, subject, so subjectivity came to my mind. I won’t remember exactly how you said it, but this question of structuring, right?

VC: The unconscious is the structure.

BB: Yes, the unconscious is the structure. It’s fascinating to delve into these topics; I see it as a step forward for them to gain more prominence in our discussions. But a bit late too, I don’t know. Maybe it’s because today I have more resources, words, but at the same time, I like to preserve my place as an artist, which, for me, initially happens in thought, and then showing it to the world. For example, I participated in this exhibition where people either entered the exhibition and start talking, or they saw the exhibition first and then stared talking. And for me, that’s where a movement happens; it’s in the order of art. As I said, I like to preserve in the sense that I don’t want to have to affirm this by word or in writing or spoken. For example, I’m very interested in talking to you, and this will become a text, a written statement. But I don’t see myself stopping too much to do that, you know?

VC: It makes sense. Psychoanalysis has an idea of text very close to textile.

BB: Weaving?

VC: Weaving, exactly. Almost in the sense that this is why the idea of repetition in an analysis is never the same. And in the sense that we can take the discourse of each analysand and produce a kind of continuity. We can affirm that is the history that alienated this subject. In the other. This history has significant points that catch him, that mark him, like the points of a fabric among so many signifiers of this story, there are those that affect this subject more. That’s why it’s possible to have two very different siblings in the same family. Because the starting point can be close in terms of what is alienating, but the entry of the older brother, and the younger brother to the older one, is very different from the younger one who is just arriving, for example. Or contingent events, for example, one day the father or mother, or the caregiver traveled, one sibling went with them and the other stayed, or perhaps the water ran out right when the younger sibling was about to take a shower. There are various events that happen that mark the history of the subject. So, we can create a kind of textile fabric from each person’s text (baggage). And the tendency of an analysis is to be able to trim this a bit, precisely in the sense that there is something very crystalline there in some places, from which the ego, or rather, the subject cannot emerge. The ego becomes very strong, like ‘I am what I am, period,’ you know? When someone says, ‘No, because I am very much like this,’ the person says this once, twice, four times, and then suddenly you see that in five years of analysis, that is not so much like that anymore.

BB: Uh-huh, yes.

VC: Until the person says something like, “I am like this, but you know what? There was a time when”…

BB: (Laughs)

VC: (laughs) you’ll see that there are holes in this fabric. In the end, this fabric is more like a braid; it’s more like a weave. You zoom in so much on the fabric that you can see that it needs a hole to be able to intertwine.

BB: Yes.

Bruno Baptistelli – Solo exhibition “4,000 A.D.” – Galeria Luisa Strina. Courtesy of Edouard Fraipont.

Bruno Baptistelli – Linguagem Escura, 2022-2023, acrylic paint, charcoal, thread, and hair, 78 3/4 x 106 1/4 in. Courtesy of Edouard Fraipont.

Left image: Untitled (Pedites), 2023, resin and 18k gold-plated copper, Ed.3 + 2 AP / Right image: Untitled (Manus), 2023, resin and 18k gold-plated copper, Ed.3 + 2 AP. Courtesy of Edouard Fraipont.

VC: The analysis aims for a bit of this trimming. It catches my attention that it took us a while to realize this, you know Beba (Bruno’s nickname)? I think resistance is a very important factor that dates back to Freud; just like the subject resists in analysis to let go of these more crystalline points because at the same time, even though they suffer from it, they need it. Freud called it the secondary gains of the symptom. Speaking broadly, a very cliché example, a child gets sick and doesn’t go to school, for instance. There could be a thousand examples. There’s always something about each person’s symptom that is also present in these secondary gains. The person’s identity is there, the family’s history is there, the suffering that keeps them connected to their father, mother, or caregiver is there. Unconscious, in the structure. There’s a lot there that if they have to let go, they will also have to let go of what constituted them… what alienated them! So, there’s a…

BB: There’s a fear.

VC: Yes, there is fear. That is why we resist it. This is the unconscious. Fear is a possible sign of this unconscious.

BB: Freud is somewhat in the popular language.

VC: Exactly. Freud differentiated fear and anxiety. I recognize fear. I have a conscious reference, fear of cockroaches.

BB: Got it.

VC: Fear of economic inflation, for example. However, anxiety, Lacan would say, is the emotion that doesn’t lie because it has no representative. And it is this state of the unrepresentable that the politics of psychoanalysis tries to address.

BB: That’s what you were talking about before. You like to bring this debate to the bar.

VC: A great challenge, given its impossibility, as politics is made up of representatives.

BB: Yes, you name it.

VC: Point me a politician who goes on TV and promises, “Look, folks, I’m going to try to change the country. But it’s tough, right? You know it’s not just about me.” No. The discourse in the election time is already a very crystalline discourse: “I will do this, do that,” and at the same time, that’s what we need. It won’t be possible to vote for someone you have doubts about. A politician who reveals their fear.

BB: And people are not able to convince themselves if you don’t name names. So there’s this repetition…

VC: But that creates a herd (laughs).

BB: That’s it, and then there’s this secondary gain.

VC: I have issues with that. That’s the crazy thing about politics. For me, that’s not the unconscious politics, the politics where I elect a representative and hold them responsible.

BB: No. Exactly.

Bruno Baptistelli – “Blues (extended version),” 2019, Installation.

Text by Hélio Menezes – A work, a text: organization by Daniel de Paula, Germano Dushá, and Leeward Wang.

VC: We confuse representation with a thing, and that’s where language comes in. That’s why, back at the beginning, referring to various things I mentioned; language as law. Because it operates based on a law of functionality too. I mentioned it earlier, remember? Freud had two things that evolved throughout his work. First, the biological became less and less predominant, making room for the symbolic. Freud is interested in the Oedipus complex, despite facing criticism. Those who critique it often haven’t delved deeply into Freud or Lacan’s work. Because the Oedipus has nothing to do with the biological father and mother, flesh and blood. It has nothing to do with the bourgeois conception of family either.

BB: Symbolic symbolism.

VC: Symbolism of a Greek hero who fulfills his destiny without knowing he is doing it. That’s the point of the Oedipus. In other words, he marries his mother, and kills his father, as it was said, by the gods’ fate. He does this without knowing. This is the point that interested Freud. Doing it without knowing that he’s doing it. Then he says, “There’s something about this Greek hero in this tragedy, that seems very similar to what I’m seeing in my patients.”

BB: This not knowing. Consequently, the lack of accountability for these actions.

VC: But he’s responding unconsciously in an active way.

BB: And it happens. That’s the real.

VC: That’s the real. In fact, Lacan spoke of the symbolic, imaginary, real. This is the real. He is staging something, and what’s curious is that people sometimes forget this moment; no one wonders: why did Oedipus have to do that? Because it was Laio, Oedipus’s father, who committed a crime. Laio kidnapped one of his disciples and violated the law of hospitality. Oedipus’s father breaks a law, and the son is cursed by this fate. Isn’t that curious? Some authors joke that Oedipus didn’t have an Oedipus complex. Because if he had an Oedipus complex…

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (1901 -1981)

BB: He would know, and he could say, what is happening that is not mine?

VC: Yes, it’s a bit of news about his alienation in the desire of the Other, or rather, in the enjoyment of the other. This father enjoys transcending a law, transgressing a law, and he pays for what the father did. This father in analysis is the ‘Big Other’. We continue to pay, for example, for a structural racism that was inherited. This inheritance, which for Freud, initially was biological, becomes this symbolic inheritance. So, the first point in an analysis touches on this symbolic inheritance. We witness a lot of repetition daily trying to address this. The bet is that we can now place another form in this ‘Big Other’ for the ones who will come next. That’s why it takes several generations too. But it’s always this relationship with the symbolic Other. And when you talk about ‘bringing the unconscious to consciousness,’ I refer to the psychopathology of everyday life.

BB: Wait. Psycho…?

VC: Psychopathology of Everyday Life. It’s a fundamental text by Freud where the first point is the shift from the biological to the symbolic, and the second point, consequently, deals with the increasingly difficult differentiation between the normal and the pathological. Initially, it was differentiated: here is the normal, here is the pathological. Freudian psychoanalysis subverted this with the unconscious. As Caetano Veloso (Brazilian singer) said, “up close no one is normal.

BB: I am still seeking to understand this crystalline idea, Freud. He problematizes himself and says: “wow, it’s not quite like that.” Is that it?

VC: Exactly. Freud conveys something through the content of his work and even more thought the form of the work, through the series of works. Because it’s visible that he is changing and questioning the statements he had at the beginning. He’s one of the authors who has the most footnotes. Suddenly you’re reading him, reading the footnote where he goes back and forth in his texts throughout his life, and when you realize that you’re actually reading three texts.

BB: Incredible!

VC: There’s a simultaneity in the text that is almost a transmission from the unconscious to Freud. And then how does he reach the point that the pathological dwells in everyone? That it’s no longer a differentiation between the normal and the pathological? Through language, once again. The psychopathology of everyday life. It takes examples from the day-to-day of what were then considered normal, from dreams, from jokes. Freud then takes formations of the unconscious that manifest in everyday language to say: ‘here is something from my unconscious that I am researching, that I am creating, that I am discovering.’ And here is something that is akin to what I see in some patients suffering from psychosis, from severe neuroses. Freud started with hysteria. So, for example, he had a patient who forgot how to use her mother tongue.

BB: How interesting.

VC: She spoke German, but when Freud started treating her, she could only speak English. So Freud investigates with her, tries to go back in time with her. When did this loss of the German language occur? She doesn’t know. She resists. Initially, he tried to hypnotize her. Gradually, he abandons hypnosis because it also put him in a position of too much power. Freud creates something called free association, with an influence from hypnosis, and realizes that the inability to react the way one would like, something that bothered, disgusted, caused anger, and the person couldn’t discharge it, turned into a symptom. A consequence of that time that crystallized in the past. The symptom that never stops being created. He increasingly sees that the symptom and the unconscious are a kind of pathology of culture. What the first patient suffered from also demonstrated a functioning of culture: repression. The need to forget some representatives, but whose affect – disgust, in this case – remained.

BB: Can you please repeat what you just said. The symptom is the unconscious?

VC: The symptom and the unconscious. The symptom is a formation that touches on the unconscious. We can say, for example, that structural racism is a symptom of our time, of many years, but now we are dealing with it. And when we think: it took a long time, right? Yes, because, for many people, it’s interesting for it to continue like this.

BB: Definitely, for many people.

VC: The resistance that the other holds contributes to transmitting a language that normalizes certain phenomena. This dynamic gives rise to cultural and social symptoms.

BB: Yes, it’s something everyone shares and maintains, and alienates themselves.

VC: Exactly, language would go in that direction, not just the word in the semantic sense…

How are we on time by the way?

BB: I can go until 12:30pm and then I need to go take care of Rosa.

VC: Great. By the way, you started this conversation talking about Rosa, right? How much you also learn from her.

BB: Totally!

VC: This is very interesting to think about what we are talking about here: What does it mean to be a father? It’s a question that touches Bruno, who is now a biological father. It’s also a question that involves a non-biological function in which you reference the other, your father, someone’s father, the older guy, the books, and also in the moment of creation. You become a partner to this other. It touches on everything I talked about regarding the law. On the relationship with this law also in moments of political campaigns.

BB: It’s the myth. It’s the myth (laughs).

VC: (laughs) Exactly. This savior father doesn’t exist. Now, until when will we resist seeing that this father doesn’t exist?

BB: And this is even more structural, right? It might even touch the creation of the gods.

VC: Man created God in his own image and likeness (laughs).

BB: Right? (laughs)

VC: He became more and more anthropomorphized. The gods in the beginning were entities. It started with animals, totemic. Until we create a God who was among us.

BB: In his image and likeness!

VC: In numerous cultures throughout history, deities were perceived as forces of nature. Even Brazilian ones like rivers, for example, or trees. But there’s something that is somewhat abstract, something natural, something animal, well, something human. I don’t know if it’s common, but when I took painting classes, there was this movement too.

My teacher always advised us to save painting the human figure for last, as it tends to pose the greatest challenge. It’s often easier to begin with still life compositions. (laughs)

Bruno Baptistelli, Self-Portrait, 2019 – acrylic and gouache on paper, 18.5 x 9.84 inches. Photos: Ana Pigosso.

BB: Oh, really? (laughs) Look, I didn’t have it that way, but maybe that’s what happened. I have a very old painting of mine, a work that I sometimes present or have presented, and I would say it’s kind of my first piece. In fact, as I speak, I wonder where it is.

VC: What is the work like?

BB: The work is a still life, a vase with lilies. It’s half painted and half to be done. It’s not a finished painting, but anyway, I remembered that at this moment. But I find this question of series very interesting, or thinking of the series as shifting in time and returning and going forward? Very, very cool. I didn’t know that Freud did that during his own production. And as you were talking about this point, I was reflecting on capitalism; how capitalism prevents this. At the beginning of our conversation, I mentioned how great it is to dedicate yourself to knowledge, and how capitalism also prevents this time for reading and thinking and conversations. We’re here. Found a window of time that I could come and chat with you. And actually, our dialogues are a series, a big series, right? Where we go back and forth, we read other things, see other topics, go through other experiences. Because also, obviously, it’s not just in this field of language. Maybe it’s another concept of language. We talked a lot about psychoanalytic language, but there are other ways to approach this concept of language.

VC: Is my previous statement too abstract, or is it clear?

BB: No, I don’t think so. When discussing body language, we learn not only from verbal communication but also from what remains unspoken. Our understanding extends to the realm of sensation, where we perceive and interpret through bodily senses.

VC: Maybe we could say direction? The work returning is a sense.

BB: Yes, it makes sense. And that goes back to what you mentioned previously, your way of reading or seeing a work of art, right? I don’t remember completely, but I think I always worked a lot in that place, trying to bring other ways of seeing, feeling, understanding, thinking about something. For me, art should have that possibility, and we should be open to putting ourselves in that place of anxiety. Perhaps, right? That anxiety that moves, that has that second moment of gain from anxiety, also in what is right, in the crystalline. It’s all kind side by side, I imagine. Thinking throughout my trajectory, maybe now I am having more opportunity; it’s kind of funny to say it like that, but I am able to exercise more this place of doubt, or they are respecting more that it is possible to have doubt. In all these years of production, I feel that there is always a demand for something, for what your art represents. So I think that’s it, I think it’s a series: you go back and forth, rethink, review. Something appears in a way that you didn’t think to put in a second, third work, in an objective way, but it’s your way of doing it. Perhaps capitalism didn’t give me time to get to these things earlier, and be able to talk about them, but I was doing it somehow, and it was affirming itself as an object in the world.

VC: It’s the unsaid.

BB: Yes, the unsaid.

VC: Not always the unsaid is the damned (laughs).

BB: (Laughs) Yeah, I’m really interested in that, that possible place. Maybe what I understand as language.

Bruno Baptistelli – works presented in the solo exhibition “Other” – Gallery of Artists (GDA) / upper left image: Hairball, hair, 2004-2019 / upper right image: ‘Bastitelio,’ speaker box, 2019. / lower center image: Amulet (in dialogue with Sonya Clark), Hair, wood, and thread, 2020-2021. Courtesy of the artist.

VC: What is language for you?

BB: Good question. I’ve been thinking, reading a bit more about it. There’s a lot of talk about different forms of communication, and most of the time, the idea of communication is an idea of objective communication. That doesn’t interest me. I think precisely the art I chose to make, visual art, has more of this power of not being objective. Because language, which is a thing within the field of languages, has a somewhat more objective place. For example, we’ve been talking for more than half an hour; there are things you said that I didn’t fully understand the meaning, the way you put it, and I believe the opposite as well. And that’s very interesting.

Anyway, visual arts, I believe, have this power to be a language. I would say it is. Now, I learned in university also that no, art is not language. Because certain professors placed language in the field of communication and believed that since it wasn’t objective, it doesn’t say that it “is” this, it is not considered language.

Returning to the question of structural racism, we establish laws. Maybe you’ll correct me if I’m using law correctly or not, but laws, or norms, of a specific dominant type. And then we think about capitalism, and how this power of domination occurs. Speaking of this (visual) field, which is mine, let’s look at other cultures; especially populations from African countries, indigenous populations, or natives, to understand, or think that there are other epistemologies, other ways perhaps of constructing language. I thought about that now, but not sure if it makes sense.

VC: Yes. The episteme is a language. When you mention that for the professor, it’s not language because it doesn’t mean something, that doesn’t coincide with Lacan’s idea of language. Language is a way for us not to think about communication theory. Communication theory, with the notion of receiver, sender, message, noise, code…

BB: Yes.

VC: It’s almost as if the code, the sender, and the receiver are very close to language. For example, in communication theory, we try to eliminate as much noise as possible for the idea to arrive as clear as possible. For psychoanalysis, noise is sometimes the unconscious. Noise can be a message.

BB: And that’s a place that interests me a lot.

VC: Yes, another example, often in the session, the analysand doesn’t want to talk about something that…

BB: Bothers them.

VC: Right. But on the one hand, you can’t force it, or you might undermine the transference, and on the other hand, you can’t just pat them on the head and say it’s okay, you don’t have to talk about it. Lacan subverts this. He says that the receiver creates the message. That’s the Other.

BB: The ‘Big Other’ is…?

VC: It’s the structural Other.

BB: Which is the one with a capital O, right?

VC: Exactly. And going back to the mirror thing, the moment Bruno says, “I am Bruno,” suddenly he sees his own image reflected and says, “wow”…

BB: This is me.

Bruno Baptistelli – Solo Exhibition “Other” – Gallery of Artists (GDA) / upper left image: Exhibition view / upper right image: Untitled, 2019-2021, Reebok sneakers,

12 x 8 x 6 inches./ lower left image: “M”, Hair clipper machine, 2019, 5.5 x 1.4 x 1.4 inches. / lower right image: Exhibition view. Photos: Ana Pigosso.

VC: It’s mind-blowing. We see many babies going through this moment of self-recognition. The baby will start to speak and has its language: he/she says, “baby wants,” or then everything will be “baby”. Suddenly everything is “daddy”. It’s so precious what a baby transmits in the step-by-step of the series he/she is doing for language acquisition. Moreover, it’s in the clinic with children that you also detect something of a psychosis, which are these transitional moments. I, another. Some can fantasize something and in a kind of, let’s say, with many quotes, a very internal world; delirium alone, delirium quietly, delirium. But then put that delirium into question. Madness is nothing more than a little step beyond that, of not having any possibility for the person to treat it as a kind of fantasy. So the other is invading me.

There’s something we pick up on this that has everything to do with this moment of transition. Something from the mirror stage also helped us think about madness, or rather, what made some neurotics manage to create a kind of separation that is illusory. And that’s what interests in analysis. Thinking about how these processes now happen in culture, for example, those who are a “threat”: immigrants, other cultures, another gender. So, the dominant, in our culture, almost always the heterosexual white man who occupies that place, he is also using the structure. So when you talk about gaining something from anxiety, I would say, how to make the dominators anxious? How can they feel anxious, since they have the privilege, in their own cultural Other, to position themselves thanks to the fact that the stranger does not inhabit him, the familiar stranger. We see then more and more policies of segregation aiming at the interest of some privileged individuals.

BB: Yes. I’ll solve a nation by eliminating everything different.

VC: Just as Freud said: money carries themes as taboo as sex. The way each person deals with money, there’s a lot we can analyze. (laughs)

BB: (laughs). That analysis will be for another day (laughs). Alright. I think I need to go get Rosa now, it’s already 12:30 pm. Thanks for the conversation, Vinão (Vinicius’ nickname).

VC: Definitely!

Bruno Baptistelli, Aquitafoda II, 2015 – Wood, Formica, and vinyl, Variable dimensions. Credits: Daniela Ometto.

To know more about Bruno Baptistelli: https://bbaptistelli.blogspot.com// @bruno_baptistelli

Vinícius Costa recommends the film The Perverts Guide to Cinema, directed by Sophie Fiennes.

– If Daffy Duck ever became a film critic informed by Lacanian psychoanalysis, this three-part English entertainment (2006) by Sophie Fiennes would surely qualify as his Duck Amuck. Theorist Slavoj Zizek, inside beautifully constructed sets matching various films’ locations, lectures provocatively and dynamically about 43 screen classics, often sputtering like Daffy himself. –

Jonathan Rosenbaum for Reader.

Hero image: Bruno Baptistelli, “Bandeira afro-brasileira (em diálogo com David Hammons)” – 2ª version, 2020, tecido, 76 x 53 inches. Photo: Daniela Ometto.