Between Studios and Streets

I often think of my studio practice as inhabiting a liminal space. For me, the studio is never simply a room with walls, it is something in flux, something that exists between the private and the public, between the interior space where I reflect and the exterior world that interrupts, provokes, and inspires me. Over the past two decades, my diasporic path has taken me across Mexico City, Chicago, New York, and Montreal. Each city has left its imprint, reshaping not only my daily life but also my relationship to the studio as a site of creation.

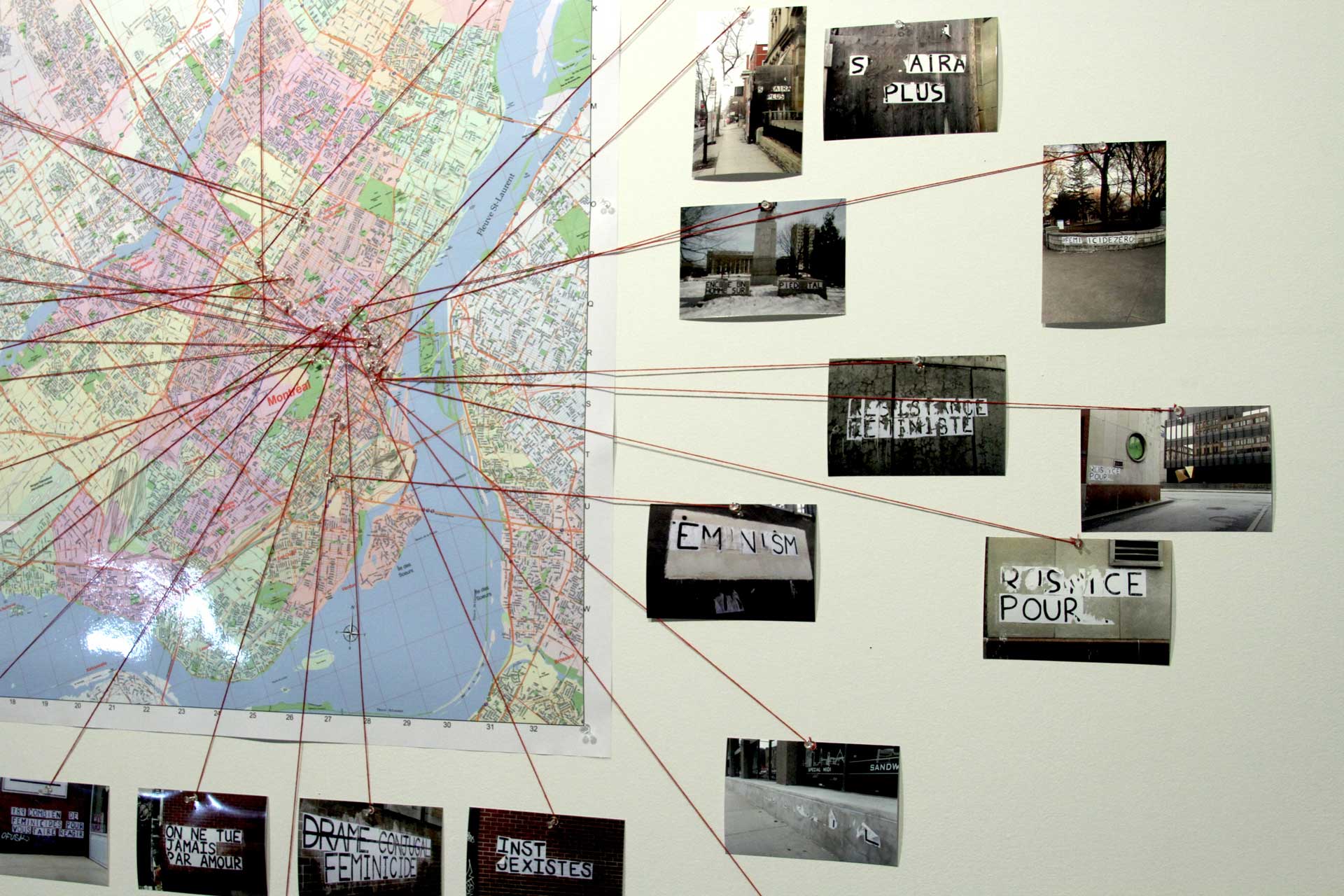

Sometimes I have had the privilege of a dedicated space, one where I could arrange objects, fill the shelves with books, and set up sound equipment and lights. Other times, my studio has been no more than a small rented room, so narrow that materials had to be piled one on top of the other. And then there have been long stretches without any studio at all, when I turned to the streets themselves as a form of workspace. In those moments, walking became a method, and the city a porous studio without walls.

The Studio as Laboratory

I think of my studio as a laboratory of ideas, a place where emptiness becomes fertile ground for experimentation. A chair, a desk, a wall, even the floor, these surfaces are not neutral; they all participate in the creative process. When I produce cut-out animations, the studio becomes a kind of magic cave. Scissors, paper, objects, and lighting combine to generate miniature universes of moving images, fragile but alive.

My most recent animations were created for a forthcoming feature film by Mexican filmmaker Javier Toscano, set to premiere in 2026. For this project, I began with the script but quickly expanded into other materials, old photographs, books, and local magazines. These fragments acted as archives, and when placed together, they generated visual metaphors that reinforced the film’s more abstract narratives. It was not the first time I worked this way. Earlier animations, such as Tracking Memory (2015) and Gigants are Sleeping (2017), were born out of a similar process: weaving memory, images, and sound into moving collages. The same approach informed video installations such as Cinco Poemas Tonales para Edificios, Chinatown (2018), produced with the URBE collective in Mexico City, and the video essay Walking in Lightness (2018). In all of these works, the studio became a hybrid space: part archive, part workshop, part dreamscape.

Sound as Core Practice

Yet, despite the shifting mediums, sound remains at the core of my practice. It is sound that structures my projects, whether through walking, radio, or installation. My studios, no matter how temporary or precarious, are always filled with sound equipment, speakers, microphones, and hard drives. At this point, I have at least twenty external drives storing media files: recordings, fragments, experiments, compositions. Some of them can no longer be opened because the formats have expired, which has made me realize that the digital archive itself is an extension of the studio. Computers and speakers are not just editing tools; they are virtual instruments, untouchable yet manipulable, shaping sonic environments that are both ephemeral and immersive.

Radio has also become an essential dimension of this work. With projects like Radio Synthesis (2024–2025) and A Radio Memorial for Gloria (2025), my studio transformed into a pirate broadcasting station. Using FM transmitters, antennas, and analog equipment, I sent sound improvisations into the airwaves, escaping the studio walls. These transmissions did not need images or canvases; they demanded active listening, creating a collective space in the imagination of those who tuned in. In this way, radio became another extension of the studio, one that redefined its boundaries and turned listening into a social and relational act.

Walking as Studio

Walking is another way I expand the studio into public space. For me, walking is not only a movement through geography but also a method of listening, a way of carrying the city back into my practice. When I record footsteps, voices, or environmental sounds, I am folding public space into the work, making it part of the studio. In projects such as Los Pasos de Mama Killa (2024), developed in Bolivia, and Third Ear Radio in Valparaíso, Chile, walking became both an alternative to having a physical studio and an exploration of situatedness. These itinerant projects revealed the porousness of my practice: the way it adapts to circumstance, turning lack of access into opportunity, and absence into method.

Fragility and Privilege of Studio Space

All of this has made me reflect deeply on the fragility of studio space today. Having access to a dedicated studio has increasingly become a privilege, especially in cities where the real estate market is both speculative and exclusionary. For me, the studio has always been contingent: sometimes available, often precarious, always shaped by circumstance. It has depended on what I could afford at a given moment, on the generosity of friends, or on the compromises of shared living arrangements. These experiences have taught me that the studio is not only a space of solitude but also one of comradery and negotiation.

And yet, every time I have access to one, the studio becomes a catalyst. It allows me to gather discoveries, reflections, soundscapes, and objects into a single place. It gives me room to slow down and think otherwise. At the same time, I know that creativity does not depend solely on a studio. My practice has been equally nourished by the streets, by collective listening, by temporary and improvised setups. The beauty of the studio lies not in its permanence but in its ability to adapt and transform, to absorb what the city offers and reflect it back in new forms.

The Studio as Ecology

Ultimately, I have come to see the studio not as a fixed room but as an ecology of practices. Sometimes it is a cave of cut-outs and light. Sometimes it is a pirate radio station. Sometimes it is simply the act of walking through the city. What unites these different versions is the way they are all adaptive, porous, and open to the contexts that shape them.

In this sense, my studio is an extension of my interdisciplinary way of working. It shifts according to the project at hand, the budget available, and the city I am inhabiting at that moment. It is constantly negotiating between the individual and the collective, the solitary act of editing a sound file and the communal gesture of broadcasting to an unseen audience. It is both fragile and resilient, precarious and generative.

I believe that every artist needs a space to think, reflect, and slow down. But I also recognize that the forms this space takes are multiple and often unstable. For me, the studio has never been a glamorous retreat, detached from the world. It has been a site of negotiation, a fragile heaven in cities where breathing room is scarce, and a porous membrane through which sound, image, and experience pass.

In the end, the studio is less about square meters and more about relations, relations to sound, to space, to others, and to the city itself. It is in this shifting ecology, between walls and streets, silence and noise, solitude and collectivity, that my practice continues to unfold.

You can find out more about Amanda Gutiérrez at @cadadosis // amandagutierrez.net

Photos: Paola de Anda, Amanda Gutiérrez, and Alexis Bellavance.