But that’s a superficial overview of his work. It goes much deeper than that, presenting a profound understanding, love, and critique of the Japanese psyche. Shohei is a silent observer of Japanese life, noting the rise and fall of trends, and how the lens of the western world distorts and misconceives Japanese culture, just as Japanese culture distorts and misconceives the western world. He grasps this dynamic in a profound and thoughtful manner, which he conveys through his art.

Shohei has two audiences: the Japanese audience and the Western audience, bringing them together to appreciate Japanese culture through a shared lens. Japanese culture, like all cultures, is not without its imperfections; its shadow is deeply flawed. The Japanese attempt to suppress this shadow, while the Western world’s filtered perspective barely acknowledges it. However, Shohei’s work exposes it to both sides, acting as the missing piece in understanding the Japanese psyche and is thus deeply appealing to both Japan and the western world. He unites these two perspectives, shedding light on the shadows that linger at the heart of every quirk in the Japanese psyche.

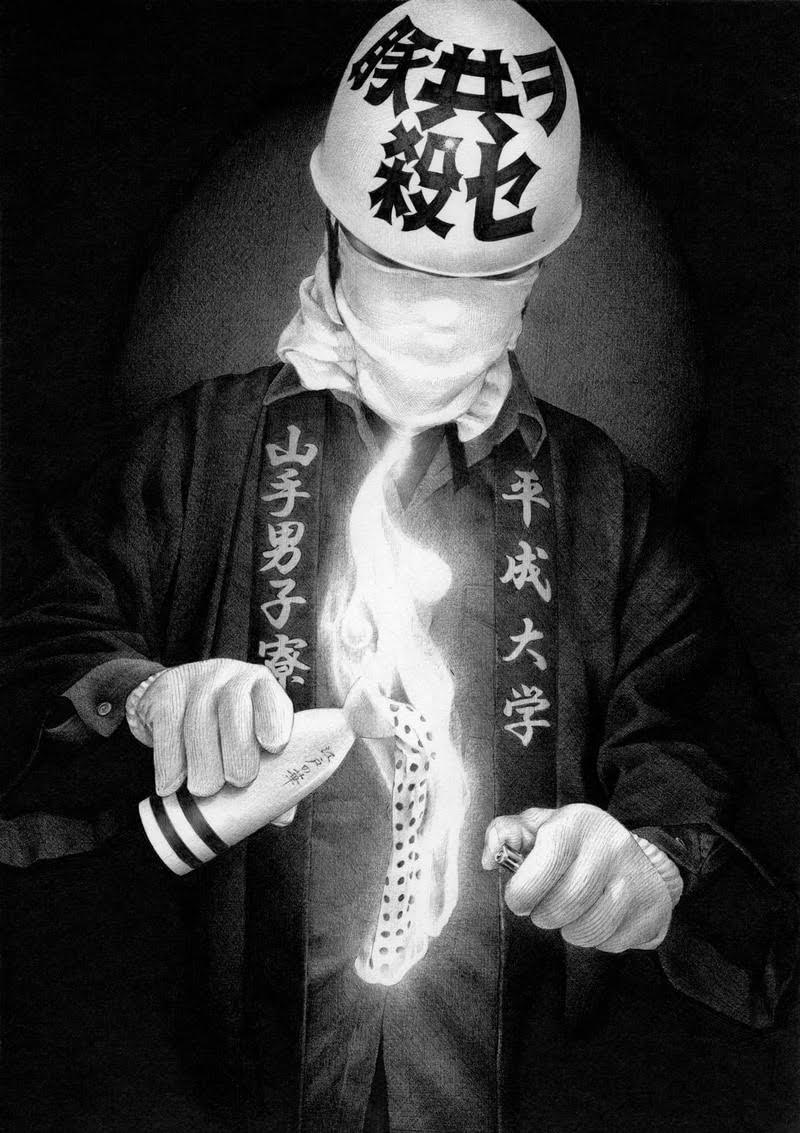

Shohei Otomo, Heisei Gebalt, 2019. Ballpoint on illustration board, 15 x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

A salient example of this is his work “Counter Strike,” a landscape piece depicting a salaryman being attacked by three kids. Each kid is adorned with iconic school backpacks and a collection of watches and keys, trophies from previous attacks. The youth, seizing the material wealth of the preceding generation, with the main youth wearing a Superman t-shirt-a symbol of Western power, corruption, but also freedom -and the kanji on his cap signifying “samurai,” a similarly potent symbol of honor, history, and violence, now corrupted in the modern era. The youth represent the eternal symbol of change, once the driving force of the Sengoku period, now a directionless force of apathy, amassing trinkets, embodying materialism. The Japanese youth have lost meaning; their energy is unchanneled, neglected by the boomer generation in their complacency within the salaryman system. Perhaps that’s just my interpretation, but these are the reflections Shohei invites us to consider when viewing his work. On the surface, one marvels at the technique, the dynamic movement, composition, and aesthetics, but the mind recognizes the symbolism, understanding its depth, even if subconsciously. And that is what makes his work truly remarkable. There are hundreds of other details in this piece alone, every badge, every piece of kanji, every pose, and detail is thoughtfully placed, contributing to Shohei’s language of analysis and critique.

Shohei Otomo, Counterstrike, 2017. Ballpoint on illustration board. Courtesy of the artist.

One could write extensively about this particular illustration, but let’s consider another example.

Shohei’s illustrations are extraordinarily time-consuming, sometimes taking as much as a year to complete, all rendered in ballpoint pen, making the process as laborious as it is rewarding. Thus, Shohei has recently begun working with sculpture. In 2017, Shohei presented his first sculptural work as part of the Ora Ora exhibition with SHDW.gallery. “There Is Nothing You Can Do To Hurt Me” is an imposing sculpture of a Sumo Wrestler covered in Yakuza-style tattoos. Sumo and Yakuza, two iconic aspects of Japanese culture, both warped and distorted by the lens of local and foreign culture but meeting in the middle through its distinct iconography. In this case, the iconography serves as a platform for Shohei’s message. The message is universal, about resilience. The tattoos comprise famous explosions throughout history and popular culture, blurring the line between the real and fictional worlds, underlining the universal symbolic power of these events. From Goku’s Kamehameha running along the arm of the sumo, the explosion from the end of Predator on his shoulder to the Hiroshima bomb on his chest, each explosion is a direct reference to popular culture and history. The Sumo, adorned with these explosions, symbolizes resilience, supported by the work’s title, “There Is Nothing You Can Do To Hurt Me.” Is this a statement about the resilience of Japanese culture, a personal statement by Shohei about his own challenges, or a universal statement about humanity? The truth is, it’s all three.

Shohei Otomo, There’s Nothing You Can Do To Hurt Me, 2017. Sculpture.

ORA ORA exhibition, Backwoods Gallery, Melbourne, Australia, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

This is the beauty of Shoei’s work. It revolves around Japan, but Japan is a complex and universal concept. The manner in which Japanese society sublimates its dark side mirrors how the west does. Japan’s cultural exports are as popular domestically as they are globally. Japan’s history of isolationism and its unique culture offer the western world an alternative view of its own psyche, its problems are the same, but the approaches to addressing them differ. As a Westerner, I cherish his work because it provides profound insight into this concept. In Japan, Shohei’s work is equally profound; he illuminates the darker aspects of Japanese culture, a punk critique of society that is eagerly understood and celebrated by Japanese audiences.

Shohei’s work leverages both cultures as platforms for observation and critique, and once one looks beyond the beauty of his work, his unique and profound understanding of Japanese culture makes it timeless, profound, and truly valuable.

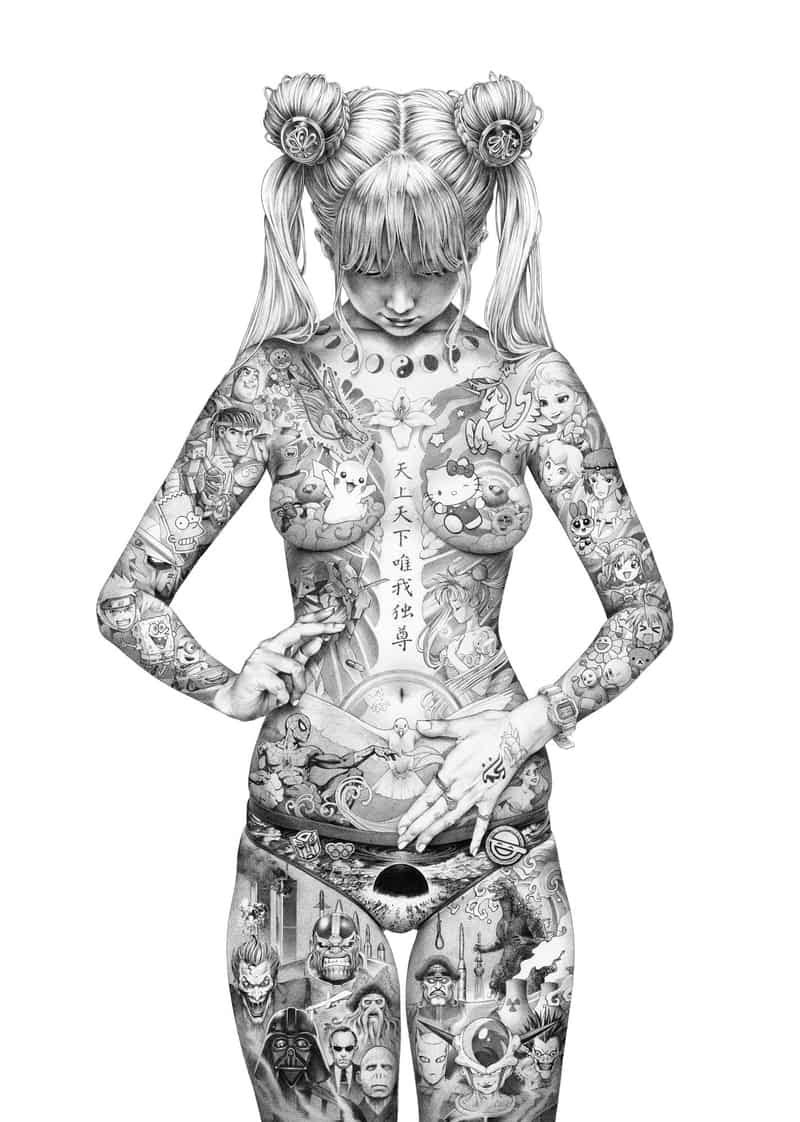

Shohei Otomo, Heisei Mary, 2019. Ballpoint on illustration board, 23.4 x 16.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Alexander Mitchell, also known as KOAN, is a prominent figure in art curation and production. In 2008, he tounded Backwoods Gallery, a pivotal establishment in the contemporary art scene. Further extending his influence, Mitchell opened SHDW. gallery in Tokyo in 2016. His expertise in merging traditional artistic methods with cutting-edge technology has established him as a key influencer in the evolution ot both media and physical art forms.

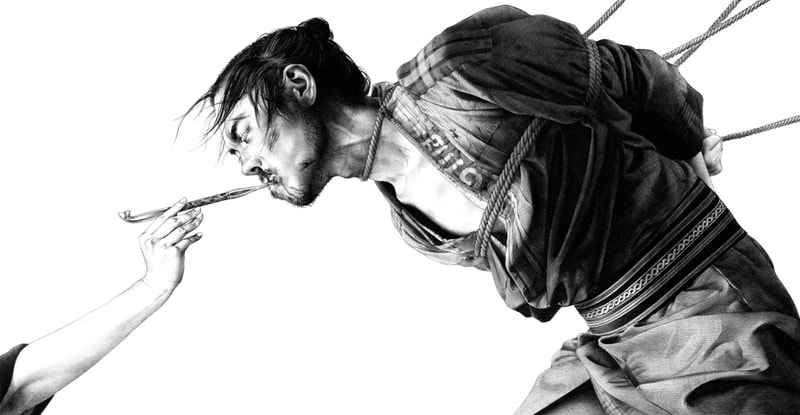

Shohei Otomo, Ippuku, 2019. Ballpoint on illustration board, 23.4 x 11.8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Working mostly in ballpoint pen, Shohei Otomo’s insightful depictions of Japan expose its commercial facade and deepest underground culture. Delivered with an unmistakable level of biting political analysis and technical perfection, Shohei’s work straddles the worlds of art, illustration, anime and cyber-punk. Since gaining online global recognition as one of Japan’s leading illustrators, Shohei has produced nearly a decade’s worth of exhibitions across Paris, Tokyo, Milan and Melbourne; worked on projects with such names as Google, Agnès B and Sony Playstation. By expanding his art practice into sculpture, Shohei has begun to solidify himself as an important figure in Japanese contemporary art.