Closing down my architecture design office left me in a creative limbo for a long period of time.

I did not have to think about a new project, I was not drawing, and I didn’t have a construction site in progress to visit. Once, during a visit to the Laser Segall Museum in São Paulo, I found out about a workshop titled ‘Creative Writing’, a course about the act of writing on Saturday afternoons. ‘Why not?’ I thought, decided to enroll, and began attending meetings with a diverse group of writers under the mentorship of a well known author.

I realized at a certain point, that I was crafting texts with the careful handling of space and timing needed in narrative storytelling. I wrote poems, chronicles, and short stories. I continue to write, sometimes letters that may or may not be sent. I understood that the 26 letters of the alphabet provide the writer with the tools to choose the best words that will lead the reader forward in reading. The secret lies in combining these letters to generate words that, when well blended, clothe the idea one wishes to convey like a second skin.

But letters, much like drawings, are complex codes. Establishing a structure is a prerequisite, not an inhibitor, to the freedom to create.

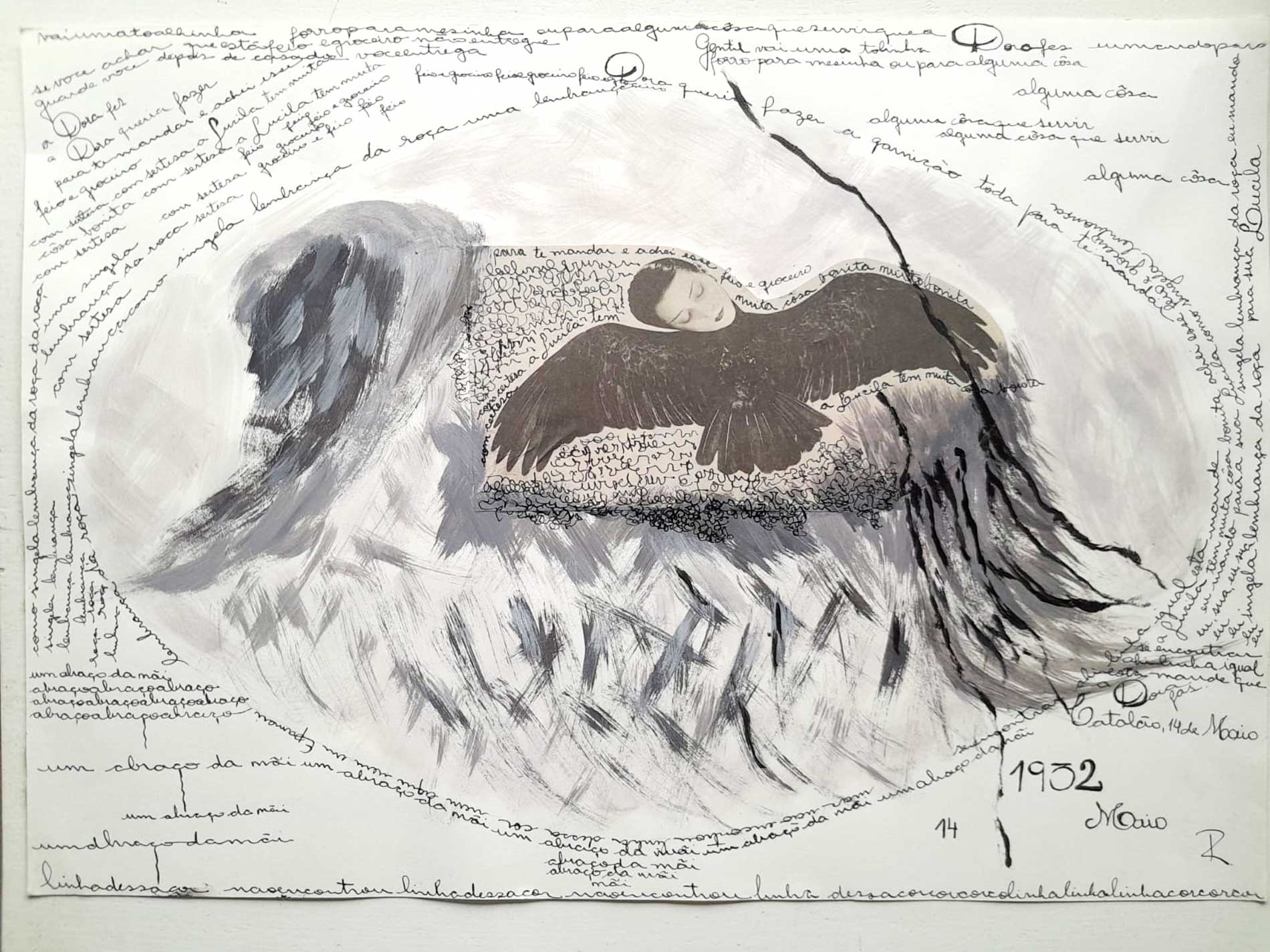

Rosely Belisqui, untitled, collage, ink and gouache drawing, 2014.

The technique imposes itself to transform an idea into something tangible: a literary text, a book, a house to live in, a city. The architect is, above all, a thinker who envisions a project in the mind and draws to record it, scrutinizing the details of the work, sizing, positioning, and gives it life.

How does an architect develop a design for a building that is different from the design created by another architect for the same building? The object of this question is to produce beauty, to allure the other. However, architecture is not only about form but also the pursuit of solutions for a set of needs that require a multidisciplinary team and systemic work.

Therefore, there is no conflict between art and technique. Just as in literary text, in architecture, form does not separate from content.

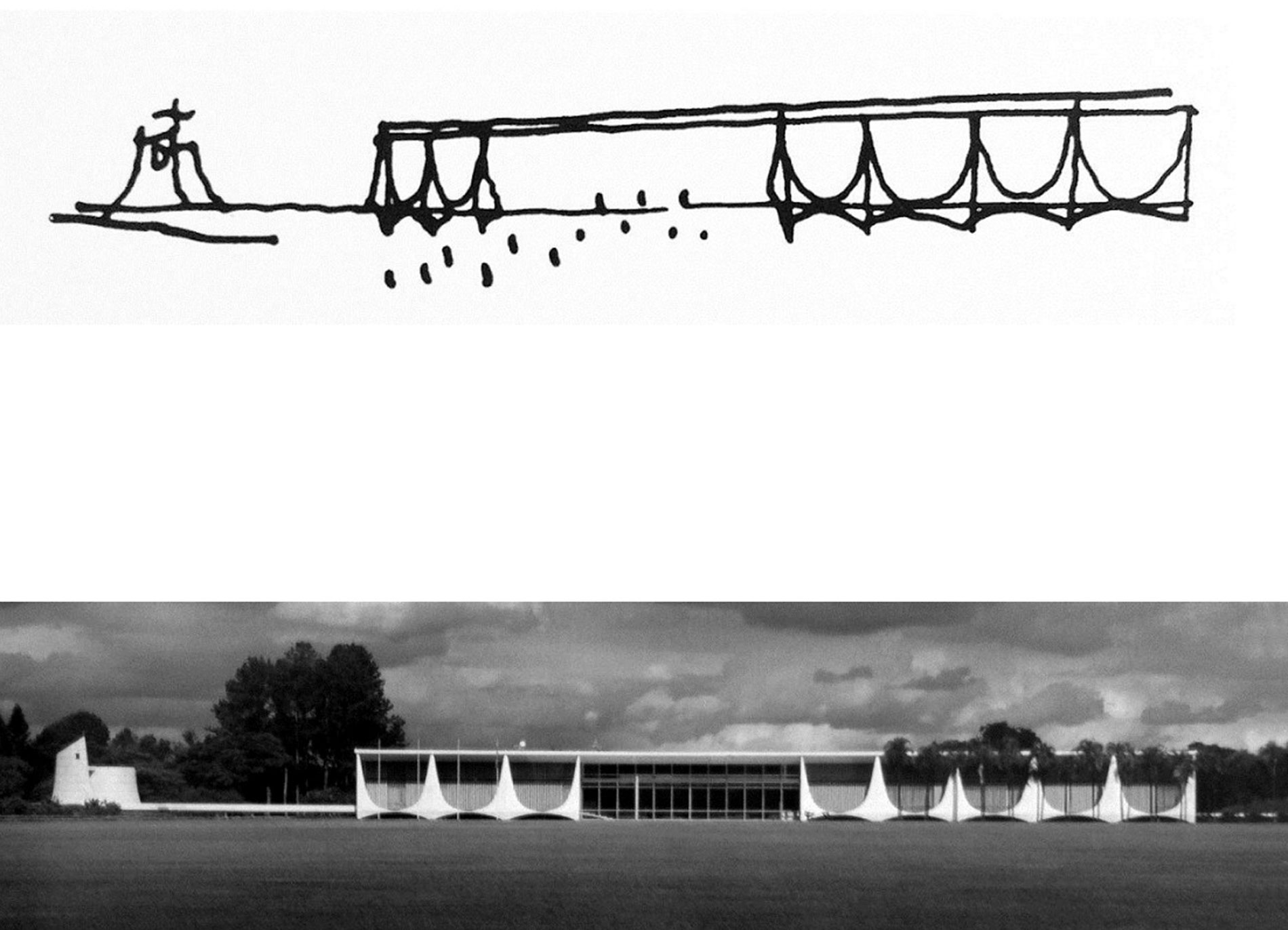

Oscar Niemeyer, sketch and built project, Palácio da Alvorada – Brasília (1957).

Oscar Niemeyer, Centro Cultural Internacional Oscar Niemeyer, Avilés, Spain (2011).

And we can also think of geography as the backdrop of architecture. The architect may contemplate occupying space with a transgressive, transformative work that doesn’t end after completion because it interacts with geography, the surroundings, making it infinitely unfinished.

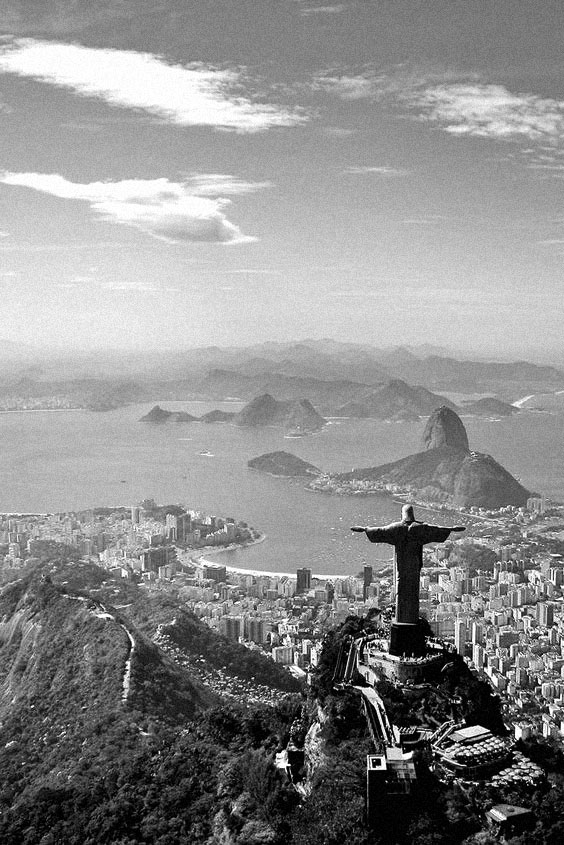

In one of his lectures, the professor and architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha(1) quotes a passage from the song “Corcovado”: “…from the window, one can see the Corcovado, the Redeemer, how beautiful…” and comments that this is a marvelous discourse. The beauty lies in the fact of seeing the Corcovado through the window. In the inside/outside relationship, the window is a divider of realities. Behind someone looking at the Corcovado through the window, there could be a child running in the room, a pot hissing on the stove, and, in short, through generous cutouts, windows not only provide natural light and proper ventilation but also offer the observer the possibility to look outside.

The city changes its landscape at a given historical moment, and a series of aspects from the past and present coexist. Thus, the architectural work is never finished and always open to adjustments and re-adaptation to its use and surroundings.

Pinacoteca do Estado, São Paulo, the city’s oldest fine arts museum, reopened to the public in 1998 after Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s intervention, which maintained the original 19th-century building as structure, adapting the spaces to the new functional needs of Pinacoteca. Foto: Nelson Kon.

Left image: Pinacoteca do Estado, foto: Leonardo Finotti. Image ao centro: Corcovado, Rio De Janeiro. Right image:Pinacoteca do Estado, foto: Nelson Kon.

I also invite you to reflect on the sense of belonging. While constructing a literary work, the

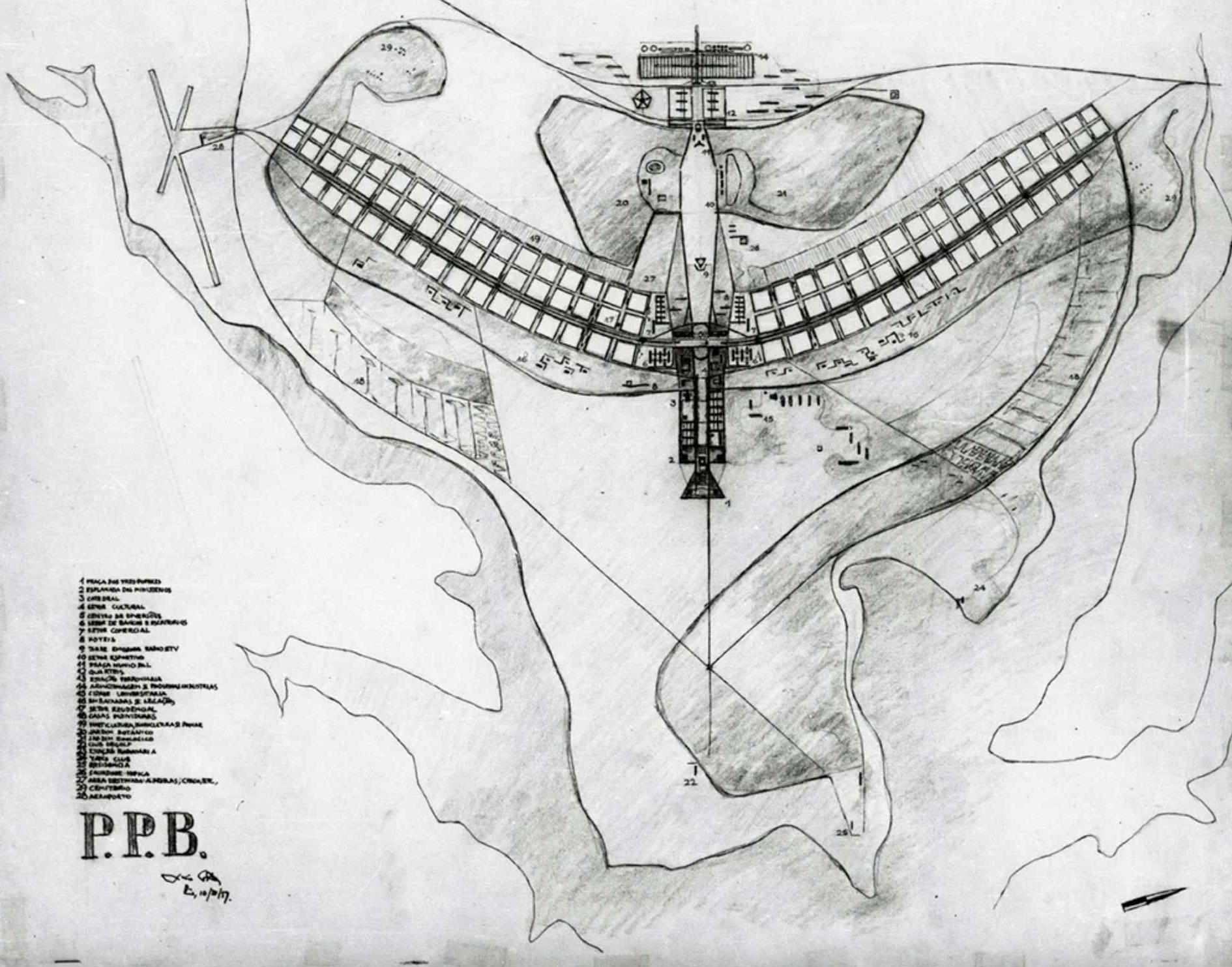

writer feels ownership of his chosen words. When the book is published, it delivers the content to the reader. As Paul Auster(2) once said, reading is the most intimate relationship possible between strangers. The text detaches itself from the hands of the writer and starts to reside in the reader’s imagination. Lucio Costa(3), the architect and urban planner who designed Brasília, the federal capital of Brazil, once stated: “The city that lived inside my head no longer belongs to me – it belongs to Brazil.”

This declaration sounds like a breath of liberation.

Lúcio Costa, Sketch of the Plan for the city of Brasília, Brazil. Photo: Public Archive of the Federal District/Fundo Novacap

Here, where I have established territory and a home, the landscape unfolding from every angle of sight is etched in the mind. When captured, it imprisons itself on paper.

The experience of connection with nature leads me to use other resources to create and build objects that I have not deciphered previously, such as stone totems that I scatter on the lawn around the house. To assemble them, I need to refer to the concepts of physics to achieve balance between the pieces.

Art, science, and technique coexist peacefully in my garden.

To speak with hands and listen with eyes.

Rosely Belisqui, untitled, ink drawing, 2019.

Anita Goes, series Névoa, Serra da Mantiqueira, 2020.

In literature, she was awarded for the short story “A Partilha” in the National Contest of Short Stories and Poems organized by the Federal University of Goiás, Campus de Catalão, Brazil.

A mother of a son and a daughter and a grandmother of a boy.

Currently, she resides in a farmhouse in the city of Gonçalves, located in the Serra da Mantiqueira in Minas Gerais, Brazil.

She actively participates as a counselor at the Socio-Environmental Institute Mantiqueiros.

1. Paulo Mendes da Rocha – (1928/2021) – an architect, graduated from the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Mackenzie University in São Paulo, Brazil, and became globally recognized. He was a design professor at FAU-USP, won the Pritzker Prize in 2006, received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for his lifetime achievement, the 28th Imperial Prize of Japan, and was announced as the Gold Medalist for the year 2017 by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

2. Paul Auster (1947): an American novelist, essayist, and screenwriter known for his extensive literary work, published in over 40 languages.

3. Lucio Costa (1902/1998): an architect, urbanist, scholar, and theorist of architecture, as well as a conservator of heritage. A key figure in the implementation and consolidation of modern architecture in Brazil. In 1957, Costa won the competition for the pilot plan of Brasília, the new capital of Brazil, inaugurated in 1960. He conceived its base on two axes intersecting at right angles – the residential-traffic axis and the monumental axis – imprinting the shape of a cross on the terrain.

Hero image of this article: Claudio Edinger, São Paulo, 2009.