My studio is located in one of those places that can be called the “heart” of Rio de Janeiro: the traditional and bohemian neighborhood of Lapa — land of malandragem, disruptive bodies, and Rio’s counterculture. It is also where, for a little over two years now, I have shared a space with five other artists. Some of them, like me, are also migrants from peripheral regions.

Rio de Janeiro has many hearts, and not all of them beat in the center.

My first studio was the street. I can say it was also my first medium and my first language. I did graffiti work and gave workshops in schools, daycare centers, and cultural spaces in exchange for materials. Through that process, I got to know many quebradas, neighborhoods, streets, and alleys… I experienced the city in its becoming, in a more visceral and true way, and cultivated a sense of belonging to it. I nurtured collectives, lived through love and danger, and believed I could be an artist. Without a doubt, graffiti was a passion, a cognitive turning point, a revelation that reshaped how I saw the world and myself. The street and graffiti were the crossroads that opened the path to my artistic practice, intrinsically infusing it with their colors, scale, and freedom.

Since 2021, I’ve lived on the well-known Morro do São Carlos*. Every day, to get to my studio, I have to descend the hill and cross this portal marked by a symbolic, structural, and dehumanizing frontier that separates us from them. Much of my research with my family archive stems from the restlessness this place stirs in me. This ancient territory — still Black, still a favela — carries a spell that doesn’t let the body forget. My body needed to return to the epicenter of the Black arrival in Brazil**, to unearth and uncover fragments safeguarded in the symbolic and ritual memory of this part of the city.

What I know — and all I know — is that my father’s family, at the beginning of the 1900s, lived in Rio’s South Zone. From there, I start this reflection while also thinking about the cartography of exclusion that pushed us, like so many other Black families, to the urban margins. This contrasts with a kind of “return” as saga, or destiny. It was inscribed in the ground. I needed to be here.

But don’t be mistaken: although the periphery is designed to function as a machine of exclusion and erasure, we had already lived through diaspora before. And we learned from it that the body — the only tool of possibility for Black people — holds memory, rhythm, and feeling. It sees in marginality and in bohemia a space of possibility for Black arts, challenging the conditions of non-humanity, erasure, and structural violence. Creating new ways of existing and imagining the world is the ritual that keeps us alive.

My research is grounded in three pillars: Body, Memory, and Territory. In my practice, I work like someone cataloging a specific part of the city, where the time of Black culture reverberates — inscribed in the body, encoded in rhythm, and etched into my own biography, which echoes the bibliography of so many ordinary people like me. To paraphrase Itamar Assumpção, with a small adjustment:

“No, Rio de Janeiro is something else.

It is not exactly love,

It is absolute identification.

It is ME.”

Sankofa. The life of Black people is shaped by the cultural and performative expressions we create. These expressions spring from a powerful symbolic force — full of meaning, pain, and affection — that, deprived of freedom, cannot be controlled and thus often manifest through chaos.

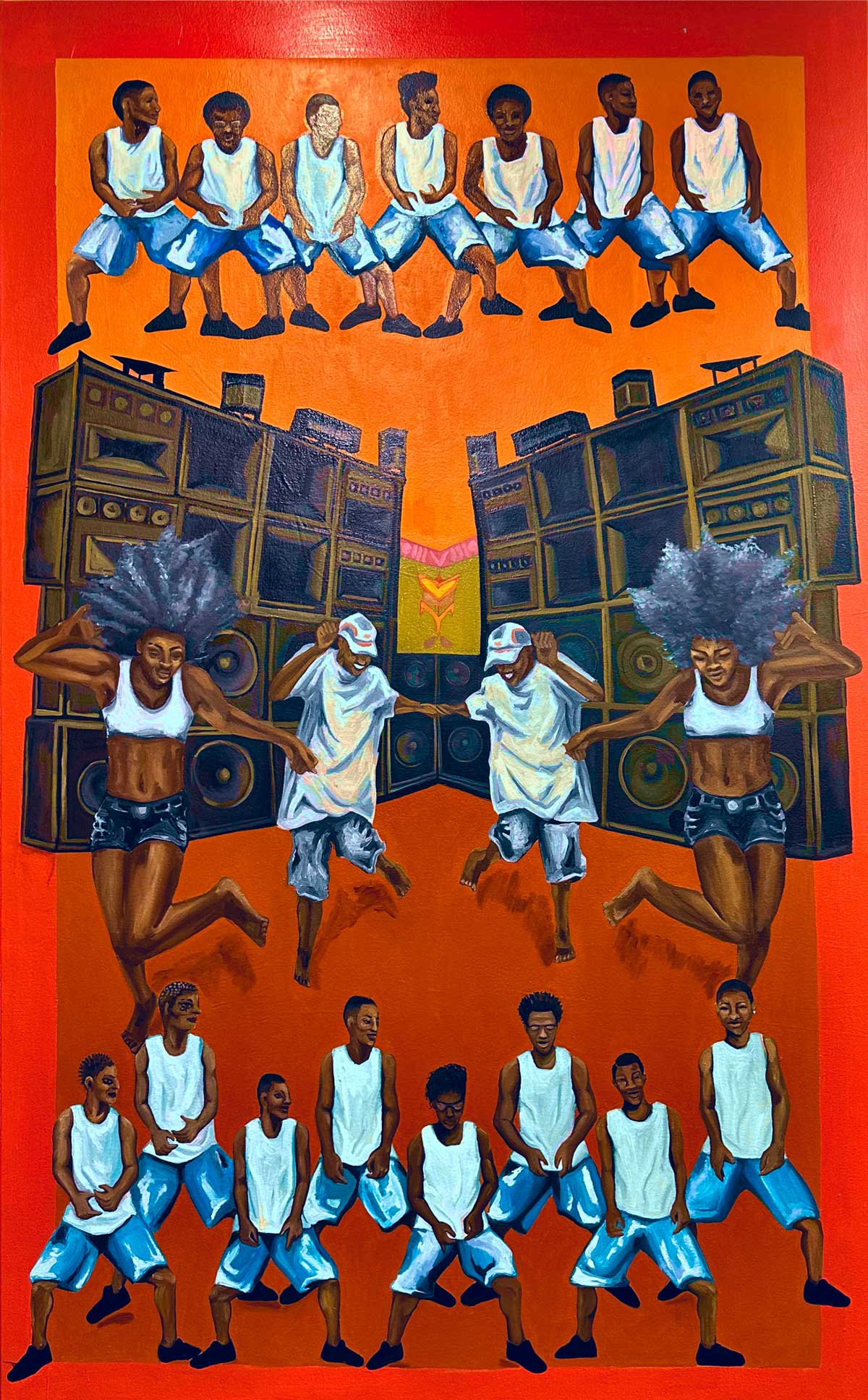

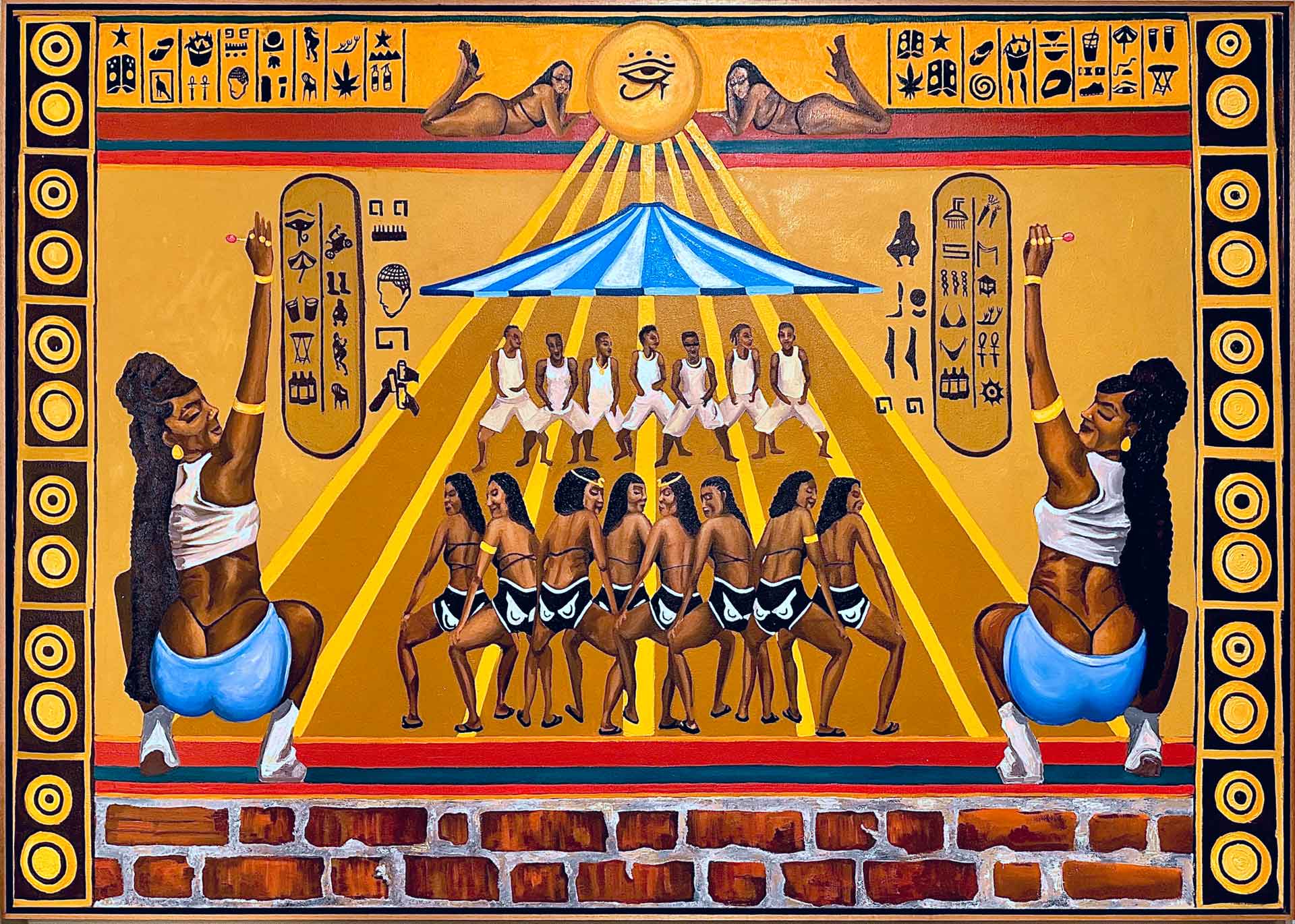

Although I engage artistically with other languages, my studio is, essentially, a painting studio — filled with the smell of oil paint. I have a small obsession with warm, saturated tones and monumental scales — an inheritance from my beginnings in graffiti and street art. Today, painting and the studio space (or lack thereof) challenge me to distill the excess. Which is not simple for someone inclined toward exaggeration and maximalism.

In the paintings that make up the series Baile do Egito and Pictografias Funkeiras, I am not trying to represent but to record images — those born from the favela, that survive through Black and ancestral time, and that also inhabit the future. The body as rhythm-ritual, where time becomes entangled. It is not about layering distinct imaginaries, but about revealing a single one.

Because we, Black people, have learned that there is a time that does not exist on the clock. A Time that is God, Inkice, Orixá…

Eró! Iroko kissilé!

The studio is the body, the studio is the neighborhood, the studio is the home, the studio is life. I grew up in Costa Barros, where the Baile do Chapadão was renamed Baile do Egito. There, the name “Egypt” sounds like a code and a spell, performing a nobility and a sense of belonging that was never granted to us but has always existed. This popular practice of renaming favelas and their parties in Rio strikes me as a sophisticated act of territorial fabulation. A way of bending boundaries and summoning new possibilities for a possible world. To organize chaos and not be lost in its labyrinth.

In this series, I translate that operation into painting, using Kemetic iconography not as direct citation or archaeological reverence but as frequency, as rhythm. The poses of funk dancers echo the profiles carved in bas-reliefs. There is something sacred in the repetition of their movements, something cosmogonic in the improvised architecture of the tarp, the rooftops, the party, the pyramids, the hills…

For me, painting is about inscribing into the present a memory that official and Western archives attempt to erase. The figures that emerge on the canvas are fragments of a collective body: bodies that have learned how to fissure Western categories of humanity and to move between the visible and the invisible.

In the diaspora, the body is the first continent.

And I believe painting, with its layered surface, is one of the places where the body can still stretch, fabulate, and re-enchant its own existence.

**Morro do São Carlos — Located in the Estácio neighborhood, Morro do São Carlos is one of Rio de Janeiro’s oldest favelas, formed in the early 20th century after urban reforms expelled poor populations from the city center. It became a cultural landmark as the birthplace of the samba school Deixa Falar (today Estácio de Sá), regarded as the origin of samba schools. Notable residents have included Zé Keti, Ismael Silva, Luiz Melodia, Gonzaguinha, Dominguinhos do Estácio, among others.

**Epicenter of Black Arrival in Brazil — The central region of Rio de Janeiro, which includes neighborhoods such as Estácio and Lapa, lies close to the former Cais do Valongo, the main port of arrival for enslaved Africans in the Americas, today recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. After abolition, thousands of formerly enslaved people and their descendants settled in the city center and in the first occupied hillsides (such as Morro da Providência and Morro do São Carlos), giving rise to the favelas. Estácio became known as the “cradle of samba” — it was there, in 1928, that Deixa Falar, considered the first samba school, was founded. Lapa, in turn, established itself as a bohemian and cultural hub, a gathering place for sambistas, intellectuals, and Black workers. For this reason, the area is understood as a symbolic epicenter of the memory of the African diaspora in Brazil.

You can find out more about Thaís Iroko at @thaisiroko

Photos (portraits & studio): Dante Belluti // Artwork images: Courtesy of the artist.