Please Read It for Me to Rest in Peace: On Misogyny and Madness

In 2018, I received a phone call from my friend and collaborator Nanda Félix. Her grandmother had just passed away, and she was living the delicate process of looking over her things and deciding what would stay and what would go. Nanda and I were working together on one of the pieces I directed at that time, “Púrpura” in which women performance artists would have one-on-one encounters with audience members (participants), telling stories about their invisible scars hidden in places in the city. “My grandmother left something that is for us,” Nanda told me on the phone. I had never met her grandmother, and was very intrigued and touched by this call. It was the beginning of a long chapter in my life, one that took me to many different places and people that I could not imagine at the time.

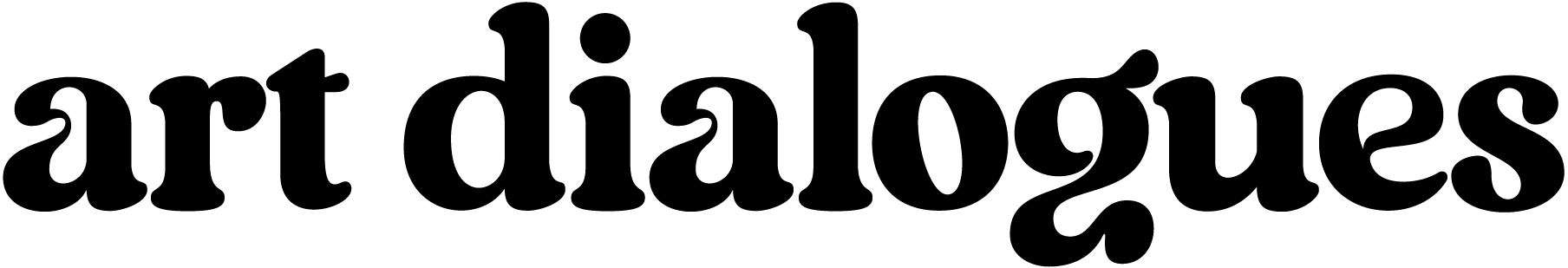

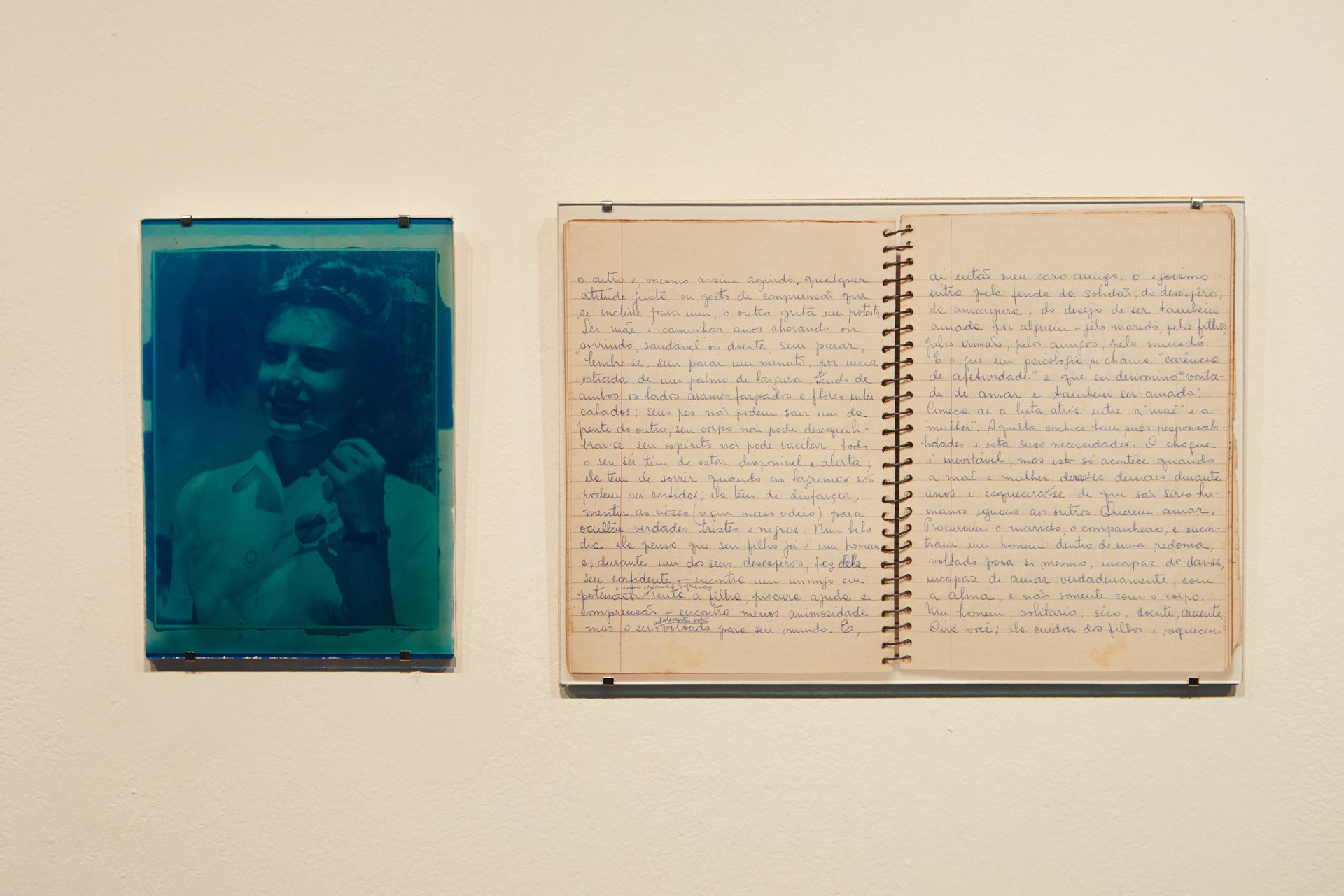

An old envelope, with a handwritten title “Please read it for me to rest in peace.” Beneath that, also handwritten: “Very private papers, sorry if I make any of my sons unhappy. The only thing I’m really sure is that I’ll never be able to keep myself alive without love”. Within the envelope, a psychological report organizing this woman’s mental health into topics, and a series of letters and confessions to a priest. In the letters, she shared her desires, anguishes and reflections about loneliness while in an abusive marriage and the search for love and for her own space. MC was committed to a mental institution in the 1950s with postpartum depression and went through several invasive treatments, including electroshocks. She was separated from her children and stopped working.

This was the topic of our conversation in that first phone call, opening the door to many other conversations in the years to come.

I am an artist of encounters. I have been dedicating the last fifteen years to listening processes that involve entering one’s vulnerability space and finding where our vulnerabilities meet. Throughout my life, I have been called insane in various situations and have grappled with anxiety and depression. Like many other women, I have always been on that fine line and the idea of insanity has threatened me like a ghost, especially in more challenging moments or when I was trying to make my way into an unknown path. On the other hand, insanity has also been a refuge and helped me to see and name forms of violence that were happening, both at an individual and at a systemic level. MC’s experience spoke directly to me. Our interest, however, was not only in reflecting on the idea of madness as a way to manipulate and silence women but, more importantly, to open a field of collective discussion. How does this experience relate to the lives of other women today?

Taking to the last consequences what M.C. had asked for – “Please read it for me to rest in peace”. Having her hidden words inside the envelope read by as many women as possible, and going beyond that. How can this experience, materialized on an envelope that was left to be read after her death, serve as an open microphone or amplifier so that women can speak up about what they would like to make public in order to rest in peace – while alive. What is it that needs to come out? How can a space of affection be opened for this collective listening? How is each individual experience of oppression different, but what are the systemic aspects that touch all these stories? In which ways is a patriarchal society maddening for women, to start with? How can we think of intersectional feminism when it comes to mental health?

Have you ever been called insane? was the title that Nanda and I put on an open call in the streets and on social media, that opened up a circle of intimate conversations with 70 women from various parts of Brazil. These first conversations unfolded into a collective encounter in Rio de Janeiro with 25 women in which the participants would read together M.C.’s report and some of her letters and then comment on them, making links with silencing experiences that they have been through. Also, we asked each woman to bring an object that she would like to make public in order to rest in peace while alive and tell her story based on the object. This was a very moving experience for everyone that was present–both participants and our crew, also composed of women. We were seated in a circle, passing the physical envelope from one to the other, speaking up about secrets – some of them being spoken for the first time – and reflecting together about the experience of being called insane.

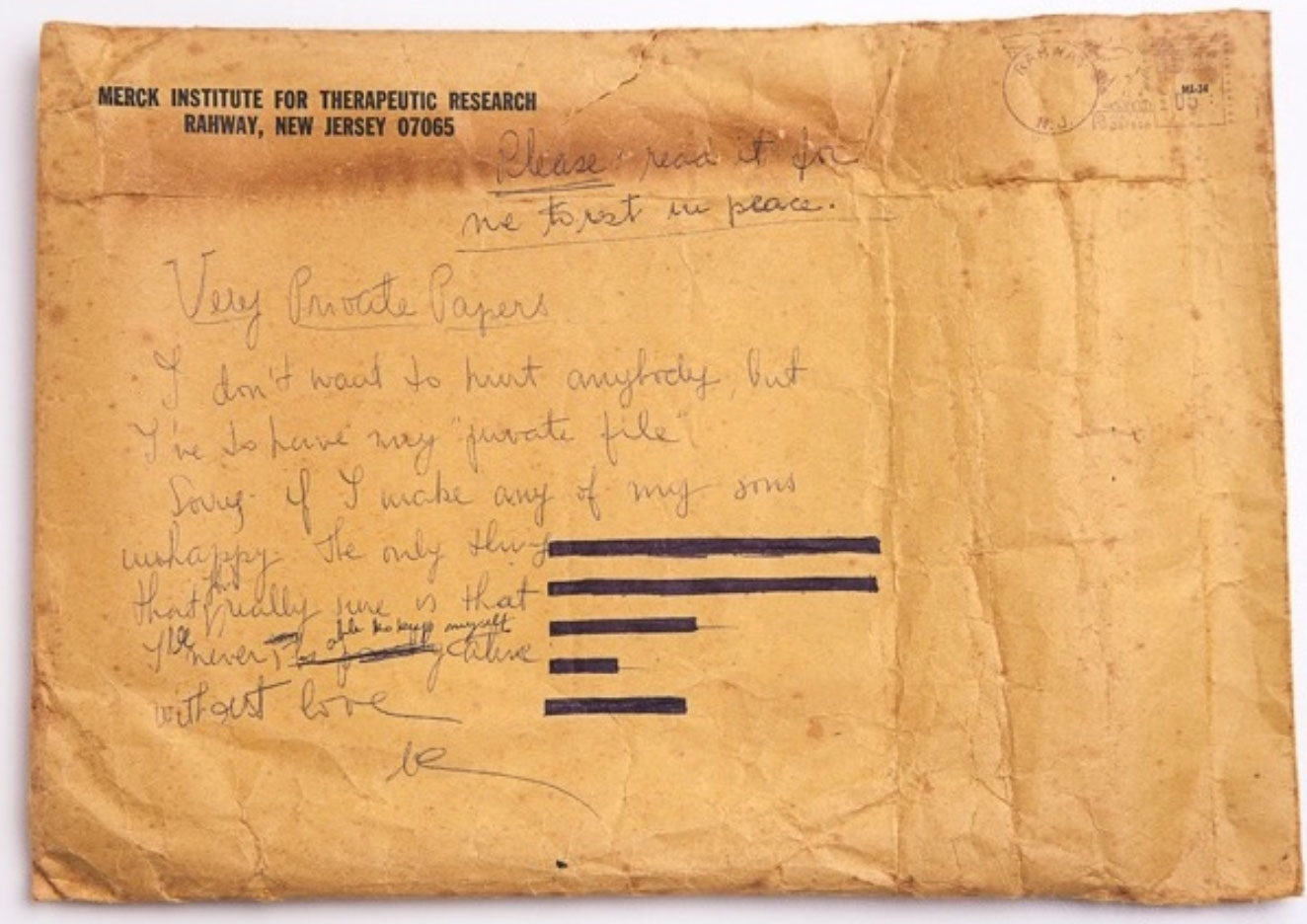

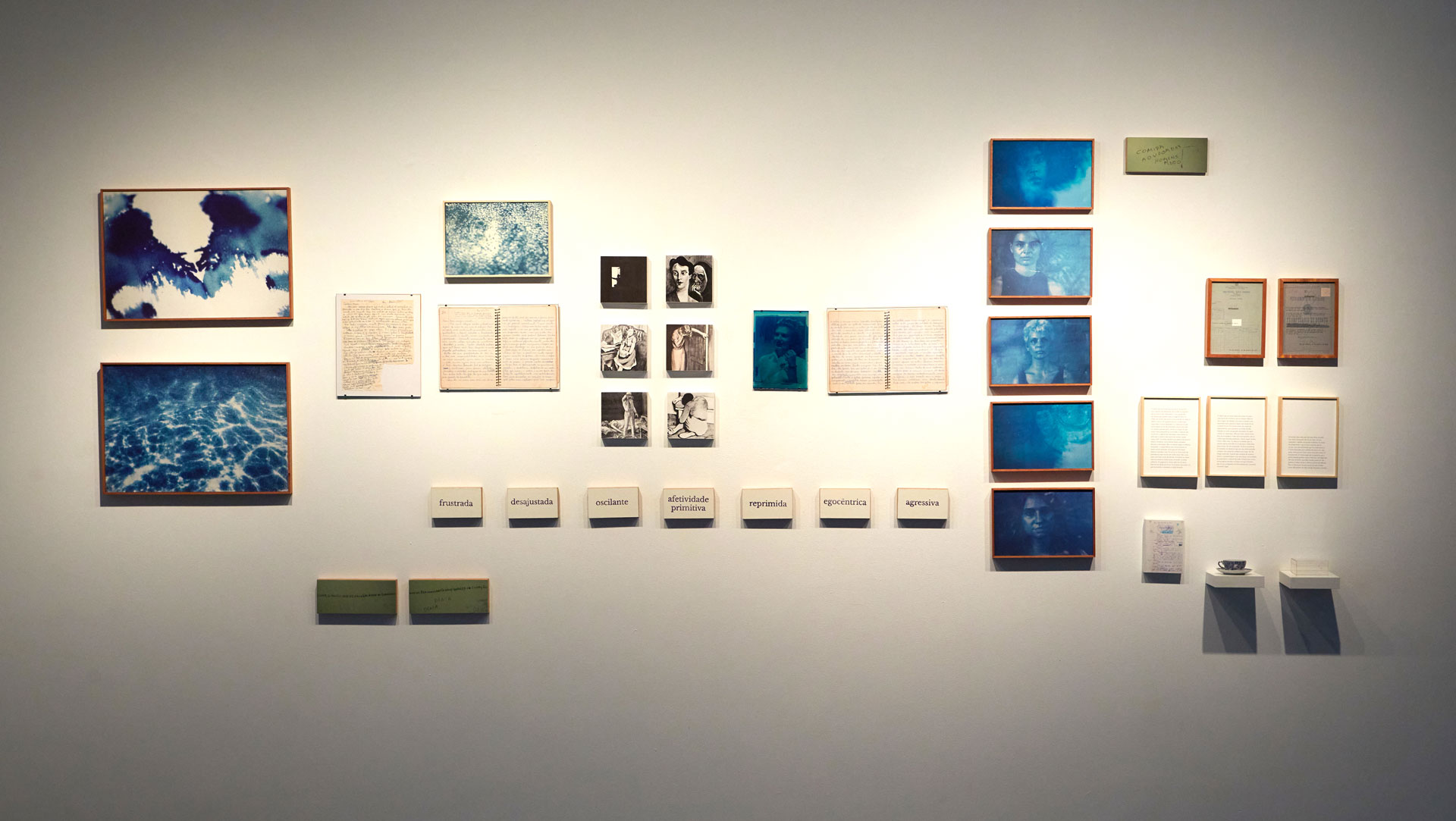

This encounter was filmed and resulted in a 2-channel video installation as well as a collection of cyanotypes, texts, and physical objects. The first film is more focused on the individual stories of the participants, with a choreography of images and gestures and the processing of cyanotypes of each woman-images that emerge from water-in addition to a visit to the Nise da Silveira Hospital, where memories of hospitalizations, including instruments, are preserved to this day. The story of these various women is placed in dialogue with the story of Nanda’s grandmother in a dreamlike and poetic montage, and her plea is transformed into a loudspeaker for cries of pain and power, overlapping times and spaces.

In the second video, we see a choir with all the women reading the report in out loud together. Gradually, this chorus dissolves, as each woman begins to emphasize words from the report and bring up others, related to their own stories-words that have been used as forms of oppression and manipulation. The experience reaches a peak of anger, a release of strong emotions and shouts, and then, spontaneously, becomes a harmonic chant of relief.

The installation is completed by a collection of objects that the women elected as representatives of what they would like to make public in order to rest in peace – a sanctuary of silences. Also, a cartography of images connected to the construction of MC’s story and to psychiatric violence, such as the representation of women in TAT tests, highlighted words on the report, writings on the walls of women’s rooms in Nise da Silveira Hospital and Rorschach tests. When entering the exhibition space, the viewer is immersed in women’s voices and stories.

Please Read It For Me to Rest in Peace was exhibited at the 13th Mercosul Biennial, Porto Alegre, and as a solo exhibition at SESC Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, 2024. The longer video piece was also shown in festivals around the globe, such as Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival and the Society for Visual Anthropology in Toronto, Canada. All the exhibition events also had new circles of conversations and activities between women reflecting on madness and silencing processes.

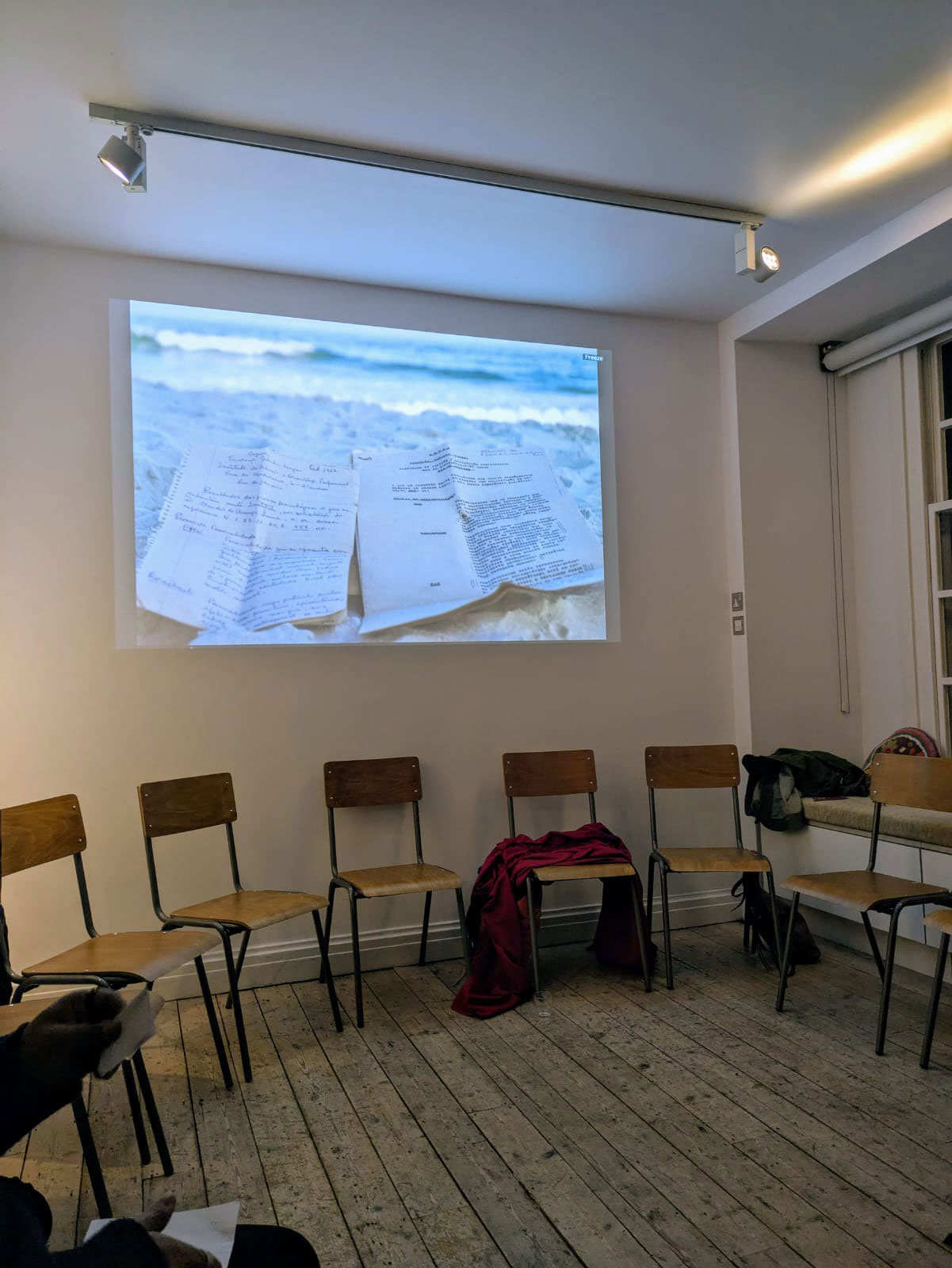

In 2025, I was an artist in residency at Delfina Foundation in London, as part of a thematic season about Art, Technology and Mental Health. I spent three months in London during the winter with fellow residents from all over the world whose inspiring practices also touched on the intersections of these three topics. During my residency, I was expanding my research about women and madness, this time more focused on sound and spoken word. At Delfina, I facilitated a salon about the project Please Read it for Me to Rest in Peace, leading a circular speaking dynamic in which women were invited to read some of M.C.’s letter, write words that have been used against them as a form of oppression, and share their experiences. It was a deeply moving experience, and, again, we were able to go beyond speaking theoretically about a subject, also bringing our personal experiences and sharing vulnerabilities. Jamille Pinheiro Dias mediated this salon.

During my stay in London, I also participated in the Creative Practice and Feminism event at the University of London, speaking about this project in relation to the idea of feminist translation and a space for amplifying feminine voices in dialogue with other interesting interdisciplinary initiatives. Presenting the project in these two different contexts and listening to women’s experiences and stories overseas was a powerful experience for me. I feel like every time this envelope is opened new layers come to the surface, not only in terms of ideas but also in terms of dynamics between the women who are present. Talking about our experiences, looking each other in the eyes, understanding the importance of just being there, engaged in listening while another woman is speaking, and knowing that care and affection are practices, not only ideas.

Please Read it for Me to Rest in Peace – Anna Costa e Silva e Nanda Félix 2022-2024.

You can find out more about Anna Costa e Silva at @annacostaesilva

Photos: Courtesy of the artist & Fabian Alvarez.