Raoni Azevedo: Well, I think a good way to start is…

Allan Weber: Starting [laughs].

RA: [Laughs] Do you remember when we met? It was in São Conrado [Rio de Janeiro], if I’m not mistaken. We chatted in that little square next to Carambola [an independent artist-run exhibition space in a large house in São Conrado, on Rua Jornalista Costa Rêgo]. You had that chin-length skater haircut.

AW: Was it at that thing Edu [de Barros] did?

RA: Might’ve been. How did you end up at Carambola?

AW: I got to know Carambola through Zé [Tepedino]. Before I started working in the arts, I did some gigs with him. Zé would call me to help the stagehands, like an assistant. One day things got really busy and he asked me to install a piece at a gallery in Gávea — explained how to do it — and I did it. Then I asked him if I could go to the show.

RA: How long did you work with him like that?

AW: About three years.

RA: That’s quite a while. We met around 2018, when Maxwell [Alexandre] was with us too. We’d been studying together since the beginning of college and he was friends with Edu. I came from a family in the countryside, from Friburgo. But my mom was a very proud person. The idea of being an artist, making personal work — that meant something to her. When I got to college, I was also kind of proud, thought I knew a lot. Maxwell was one of the first people I talked to, but what was cool was that instead of getting insecure around people who knew more, he went after things, asked questions. That’s how I met Edu. And maybe that’s also how I met Zé. I don’t remember exactly.

AW: So you met Zé at college?

RA: Yeah. I studied with him, Maxwell Alexandre, and Edu de Barros. Zé was also friends with Demian [Jacob] and other childhood friends of mine. His whole family knows mine through that Sufi group [Sufism is a mystical branch of Islam focused on self-knowledge and direct connection with the divine, with practices like meditation, poetry, and philosophy. It shares affinities with other mystical traditions, like Kabbalah, Hinduism, and contemplative Christianity], which was a big influence on me too — taught me a lot about storytelling, thinking in metaphors, how to pass on knowledge and such. That really stuck with my practice. But it’s funny that we met way back then. It was right around when I moved to Rocinha with Maxwell and we started A Noiva – Igreja do Reino da Arte [an art collective and artist residency space in Rocinha, a favela in Rio de Janeiro] because people were hanging out a lot in the studio and this crew started forming.

AW: I met Zé when I was working in the stockroom of an Osklen store [a Rio-based clothing brand] in Ipanema. Since I lived in Cinco Bocas, up in the North Zone, I’d stand for two hours on the bus to get home because the [Via Elevada da] Perimetral still existed back then, you know? I didn’t go to the South Zone, so it was all really new to me. I’d be like, damn, I’m by the beach all by myself! Posto 9! Legalize!

Valentina Tong, Basalto I e II (díptico), 2023, Pedra Paulista,55 x 55 cm. Impressão UV sobre tecido Cedro Prata. Cortesia da artista.

RA: I had that same experience with the South Zone and with Rio, since I’m from Friburgo. I used to get lost all the time, like when we traveled recently to that new city, Nottingham. That’s how I got to know Rio too.

AW: I remember the first time I skipped school and went to the beach in secret, I got grounded for weeks. It wasn’t until I started working there that I began going more often — I was about 15. Then I ended up at the skatepark at Lagoa and met a crew who also listened to rap and smoked. It was through skate friends that I got closer to art.

RA: I came in through design. Everyone in my family is a problem-solver: my mom’s an architect; my younger brother works in nutrition, but now has a job in customer service; my older brother does event production. And I got into design. When I met Maxwell, who was this super funny guy, I realized we had the same interests. I think we still connect through that — people with fire in their eyes, you know? People who are really alive and paying attention. You recognize that in someone. We recognized that in each other in college, and he introduced me to skateboarding, rollerblading, rap culture. I got into all that through him. My mom comes from a Workers’ Party [PT] background and has been a PT supporter since she was young. Half of my family’s anarchist, the other half communist. And my mom always told me how important it was to talk with everyone.

AW: I felt that same curiosity. In the favela, it was always the same people, the same routines — funk parties, pagode, the usual spots. But when I started spending time in the South Zone, I noticed how differently people dressed, how they spoke, how they carried themselves. It made me curious. They talked about things I wasn’t used to hearing. My whole family came from an evangelical background, so the path was always clear: go to church, follow God, no questions asked. I went, but it felt forced. I didn’t connect with it. I think because that was all I knew growing up, I naturally started to seek out other experiences once I got a glimpse of something different.

RA: I feel that. My spiritual upbringing was pretty much the opposite. My mom, who’s from Minas, used to say, “We’re in Friburgo, but we’re not from here. People here can be closed-minded — just remember to keep your mind open.” So I always had this sense of not quite belonging, even though I had a peaceful childhood there. It was good — we were always outside, riding bikes, hanging at each other’s houses, getting lost. The whole town felt like it was ours. But I don’t keep in touch with anyone from school. My real friends came from a Sufi group — a mystical branch of Islam, though that’s a super simplified explanation. It played a huge role in shaping me. My dad left early and we eventually lost touch. My mom raised three kids on her own. And that group gave us examples of other families, of strong, present men raising their kids. I became friends — almost like a nephew — to people I admired. That gave me grounding. So the spiritual side, that “church” space, was something I actively chose to have in my life.

AW: That’s cool. It’s funny—after my time with the church, I found myself drawn to the Church of the Kingdom of Art because there, I didn’t feel any pressure, you know? The pressure only came later, after I became an artist, because of the work itself. But back then, everything was so new to me. That’s also when I met Primo da Cruz [Brazilian artist, 1983-2020], the only person I really connected with who was from the same place as me. We didn’t talk about art—just about life and our roots. I’d already wanted to make art before—photography and video—but it was then that I started feeling the urge to build objects and explore those possibilities. Seeing people from Rocinha doing it made me realize, “Hey, I can do that too.”

Valentina Tong, Mina Brejuí, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 48 x 65 cm. Impressão UV sobre TNT prateado. Cortesia da artista.

RA: Absolutely. I’ve been into making things since I was a kid. My mom didn’t like buying stuff — instead of buying a nativity scene, she’d craft one from leftover pieces from her architecture models and taught us how to glue things together. So from a young age, I was always taking things apart and putting them back together. I loved understanding how things worked. That’s why I pursued design and later got into film. I still have a deep love for cinema, but it didn’t quite pan out. When I started working in the art department, I realized to really create there, I needed to understand theory. I thought, “Damn, I either go to college or I’m stuck being someone’s assistant forever.” Design school offered a bit of everything — photography, video, theory, history — so I shifted away from film and along the way, thanks to some professors at PUC, we discovered art and dove in. But liking it wasn’t enough — we wanted to fully immerse ourselves in it.

AW: That’s really awesome—how being hands-on has been part of you since you were a kid, taking apart toy cars. You’ve always been a maker. It reminds me—I wasn’t the kind of kid to take things apart, but I was always inventing games. My little brother was really young, so I often played alone. I’d build elaborate worlds for my action figures and play soccer on the rooftop, acting as both teams. I think this drive to create and reinvent has been with us since way back.

RA: Have you heard of the book Letters to a Young Poet? It’s a series of letters exchanged between a young aspiring poet and the renowned poet Rainer Maria Rilke. We read it early on, and it really left an impression on me. I say “we” because it was a close-knit group—myself, Maxwell, Eduardo, and also Cario Rosa, who’s a photographer and now based in São Paulo.

AW: And there was also [Rodrigo] Rosm.

RA: Yeah, Rosm was always around too. He worked on editing artist books—he runs a publishing house [Casa27], right? It was a whole crowd moving around. Maria Antônia [Souza], an incredible painter, is still around, and the graffiti guys too. The three of us were close, but we were also connected to this wider network. Anyway, back to the book—Rilke says if you really want to know whether you need to do something, you have to lie down at night, when no one’s around, and ask yourself if you need that thing in order to exist. And if the answer is yes, then it’s probably something that’s been pulling at you since childhood. Something like that—I might be making it up [laughs]. But he says that most of your work will come from that source in childhood. And I believe that. Like, I had to learn to be very diplomatic and strategic, and that’s basically what I do now with the artists I work with—like with you.

AW: Where do you think that comes from?

RA: I’m the middle child, man! My mom was a strong woman who had to keep three kids in line. When she took on that commanding tone, all three of us fell silent. My older brother was much bigger and way more energetic, and my younger brother couldn’t complain about anything. So I had to learn how to negotiate and read the emotions behind what was being said. I’ve always been a somewhat anxious kid, which made me really attuned to these subtle cues and helped me act strategically. I’ve also always enjoyed connecting with people and visiting their homes. I think that’s closely tied to the kind of “translations” I do—not just between languages, but also between conversations and spaces.

AW: That also led you to move through different places, right? You have this ease of circulation, and that helps you understand and interpret or translate those places.

RA: Exactly, and maybe that’s why we share a familiarity. We recognize in each other that desire to get around. I’m really impressed with your ability to be out on the street, to see the movements happening. You’ve always been interested in observing street life—how people relate, who does what.

Valentina Tong, Cânion dos Apertados I, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 38 x 51 cm. Impressão UV sobre EVA brilhante. Cortesia da artista.

Valentina Tong, Cânion dos Apertados I, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 38 x 51 cm. Impressão UV sobre EVA brilhante. Cortesia da artista.

AW: I always took refuge in the streets. Since I was a kid, the streets were my escape, you know? If I was grounded, I’d run to the streets. Even when I went to church, as soon as I got out, I’d stash paint inside a guitar and head out to tag walls. I always felt at home on the streets, and a lot of what I’ve done in life happened there. I never finished school—so everything I know, I learned on the streets. And you mentioned learning to be strategic… For me, that came largely from tagging and observing how the drug trade operated, especially their tactics for controlling spaces and territories. You had to be strategic about where to tag: Which spot? How long will your tag stay up? How will you get to that place? How will people passing by see it? There’s a sharp strategic and aesthetic sensibility in all of this, and I think that strategy—the kind of curation involved—is how I position myself today. I started making art through tagging, though I didn’t call it that at the time—I was just using strategy to stake my claim.

Valentina Tong, Mina Brejuí, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 48 x 65 cm. Impressão UV sobre TNT prateado. Cortesia da artista.

RA: That’s very clear in your work. It has the impact of tagging, of seizing a space opportunely. Like: you left this space blank, so let me take it and maximize the impact.

AW: And also about durability, because for a tagger, the longer the “work” stays in a place, the better. But it’s hard to explain how to do that. When you see a tag nowadays on a small window or a store, dated 2000 or 2005…

RA: Those ones by the old Perimetral entrance. The guys hit those overpasses, and no one ever painted over them or touched them—their tags are still up to this day. That always blew my mind.

AW: And that’s a real mix of strategic and aesthetic precision. They were already thinking about aesthetics when creating a name. It’s wild.

RA: If the city ever gets its act together, they’ll have to restore that tag like they did with Gentileza’s [the Rio artist], because it’s already part of the city’s history. We got on this topic because you consider yourself a traffic expert, and we were talking about the street—your comfort zone. For you to go out and work as a delivery guy in the middle of the pandemic… For me, that would’ve been terrifying, but was it chill for you?

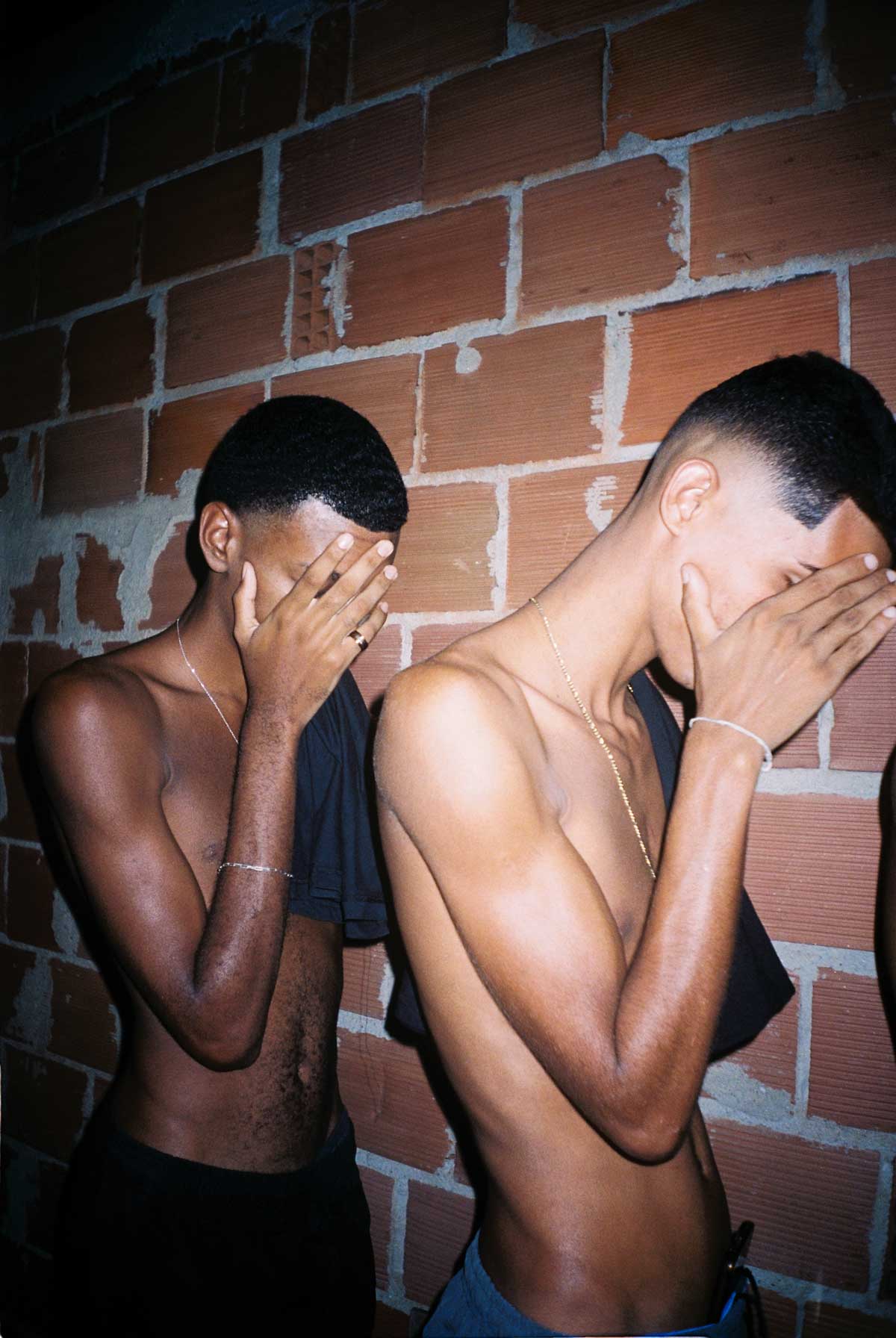

AW: Yeah, it was. I was really worried—my son had just been born in 2019, so he was all I could think about. But I don’t remember panicking. I didn’t have a steady job with Osklen, just freelancing for Zé and getting paid by the day. When the store shut down, Tom had just arrived, and then the pandemic hit. I had to work, so I got a motorcycle and started doing deliveries. Then we all caught COVID, so we had to stay home for a while. I was anxious not being able to work, but everything worked out and I got back to it. In the favela, there wasn’t really a stay-at-home culture. Things slowed down a bit, but people were still out. The local traffickers actually banned folks from walking the streets, so the younger kids went up to the rooftops to fly kites, hopping from one to another. That’s when I shot a photo series up there, right where I live.

RA: So at that time, you were already thinking in terms of a photo series, already aware that what you were doing was art?

AW: Yeah.

Valetina Tong, Itatim, Bahia, 2021. Cortesia da artista.

RA: Was there a specific moment, like a starting point?

AW: Not really. I just kept taking photos, and then the book came out. I had never made an actual object before.

RA: Did Demian help with the book?

AW: Yes! At the time, we had this group that would meet up—everyone helped choose the photos and even pitched in to fund it. We kept it super low-cost, black and white printing. And it was really dope because it was during the pandemic, when no one was going to exhibitions. A book was the best way for people to engage with art. You guys stayed in São Paulo for a while at Cropped, right?

RA: Edu and I got there the same day they shut down the highways, and we ended up staying for four months. It was a wild shift—we’d head up to Paulista Avenue in the middle of the night and it’d be completely deserted. We were staying at the gallery in Sé, which didn’t have much in terms of infrastructure—it was a tiny space—so we had to find ways to get out of the house a bit. After four months, we were sick of looking at each other and headed back to Rocinha. Edu’s parents pulled off a full-on rescue mission—drove to São Paulo, packed everything up, and brought us home.

AW: I remember. I followed you guys online.

RA: The online thing was a huge hit, and Edu’s work really blew up after that.

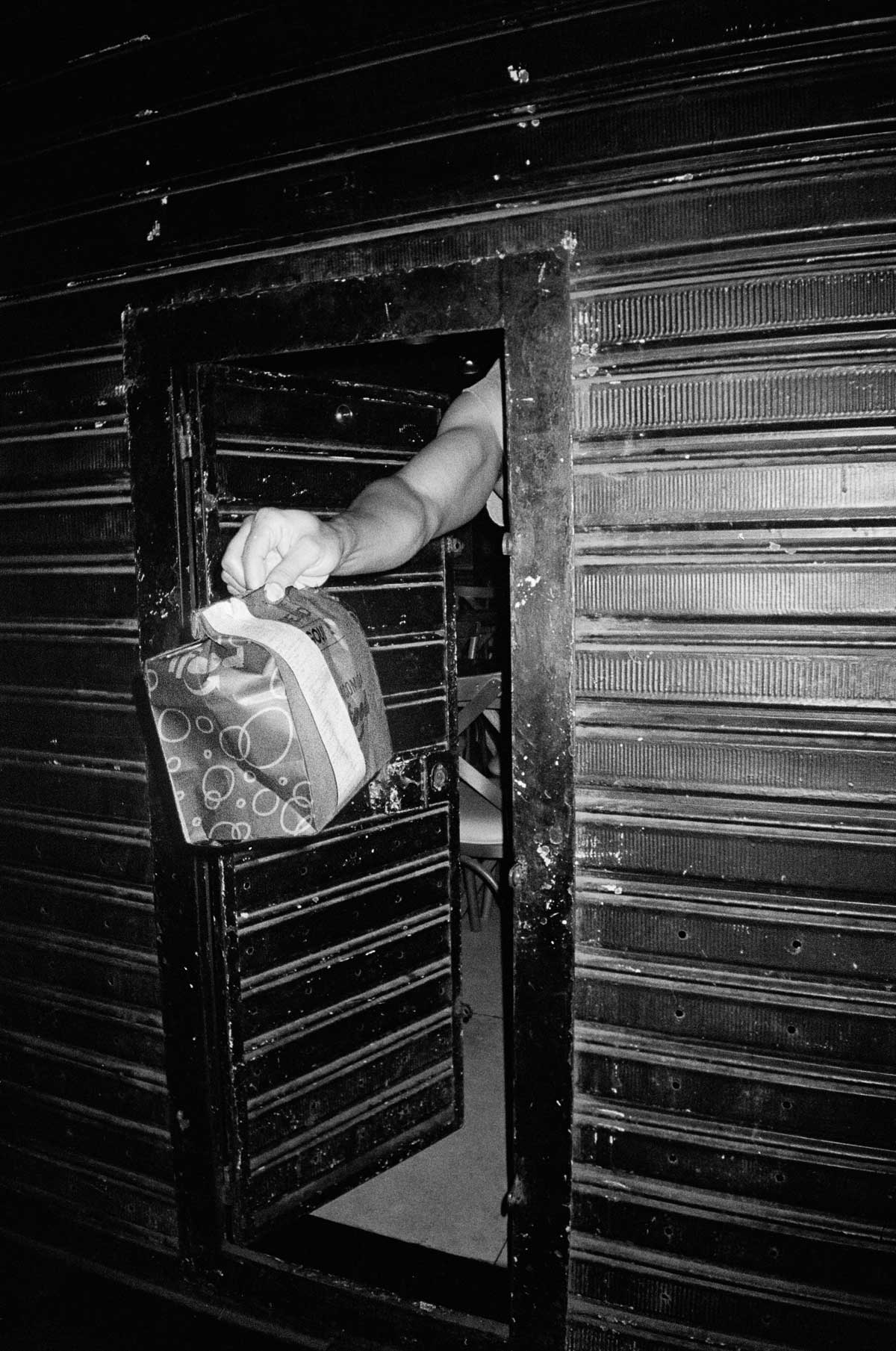

AW: The book was like that too. I’d deliver copies in the morning and then head straight out to deliver food.

RA: That’s dope. I remember—you came to Rocinha to hand me the book. And that’s the thing… Living in Rocinha meant being close to the stories I was living. I’ve lived in Botafogo too, but I was never from Botafogo. I think now is when I’m finally starting to feel more like I’m from Rio. But in Rocinha, I was seen as a playboy. I am a playboy. I move around a lot and know how to switch up codes, but in Rocinha, people could tell.

Valetina Tong, Itatim, Bahia, 2021. Cortesia da artista.

Valetina Tong, Itatim, Bahia, 2021. Cortesia da artista.

AW: I lived in São Conrado when I got married, and then I moved back to Cinco Bocas. When I was living in São Conrado and working with Zé, people thought I was a playboy too. And when I talked, people thought I was faking the slang. And because of my name too… People think Weber sounds like some foreign photographer name, but in reality, he lives out in the middle of nowhere [laughs].

RA: [laughs] It’s like a migration within the same city, right? But you can move through different spaces too—like recently, when you traveled for that residency. When I got there, you already knew everyone, even without speaking the same language. That’s a skill too. Sensing who shares your same background and connecting—like with that Egyptian guy who cut your hair.

AW: People like us learn a kind of eye-language early on. There’s this line from Tz da Coronel where he says [singing], “Reading looks, I learned with time / Love is only from mom, I learned with time / Nothing’s changed since then / And the method, no mistakes, that’s my foundation / Still undefeated.” When you grow up in a place like that, you can spot someone else from the same world just by passing them on the street. I don’t know if it’s a social code or what—but you feel it, even in another country, in a totally different culture. And when I think about it, favela kids grow up practicing creativity. You don’t have the toys you want, so you make up your own games. My mom always tells this story—when I was four, I had a bike with no seat and no pedals, but I still rode it. And everyone wanted to try it, even kids with real bikes. But only I could pull it off.

RA: Totally. It’s funny how all these childhood memories keep coming back. We really did build a lot from nothing. I used to make juggling balls and sell them at school.

AW: What do you mean?

RA: Like for juggling. I’d buy party balloons, fill them with rice, and sell them. I also sold drawings and cardboard airplanes. They flew like crazy! We weren’t in a totally dire situation at home, but it was tight. My mom was always working hard, never home much, so a lot of it was about inventing ways to stay busy.

AW: Yeah! I also used to make soccer goals out of scrap wood, nails, and potato sacks for the net. I was really into soccer. I also used to grab wires from Telemar [a telecom company]—they’d rip them out and leave them lying around—and I’d use them to make bracelets and medals, combining them with bits of leather.

RA: [Laughs] Damn, I made braided bracelets too, but mine were way more hippie. You built a skate ramp later, right?

AW: I did! And only after that did I start working with skateboarding.

RA: Funny—whenever I figured out how to do something, I’d lose interest and move on. What really drove me was understanding how things were made. At first, I tried to be the face of my own art, but I’d get bored fast. What I really enjoy is teaming up with someone who’s passionate and helping take their work further. I did that with Maxwell, then worked with Edu for a while. I spent a long time as Maxwell’s studio director, and when I left, I thought I was done for—I had nothing to show. But then opportunities started showing up, and you invited me to collaborate. That’s when I realized what I’d been doing could actually be a career.

You said something earlier when I mentioned helping my brother—that I let him play loose. That’s exactly it. My role is holding it down so others can shine. I don’t need to score; I just want to set up the play. I like playing as part of a team.

AW: For sure. I think being a team player is super important. Everything I learned in the community is tied to teamwork, right? The name says it all… everyone helps each other. The community comes together to organize a festa junina [Brazilian traditional winter parties], a St. George’s feijoada, or something when someone dies. There’s a real sense of unity.

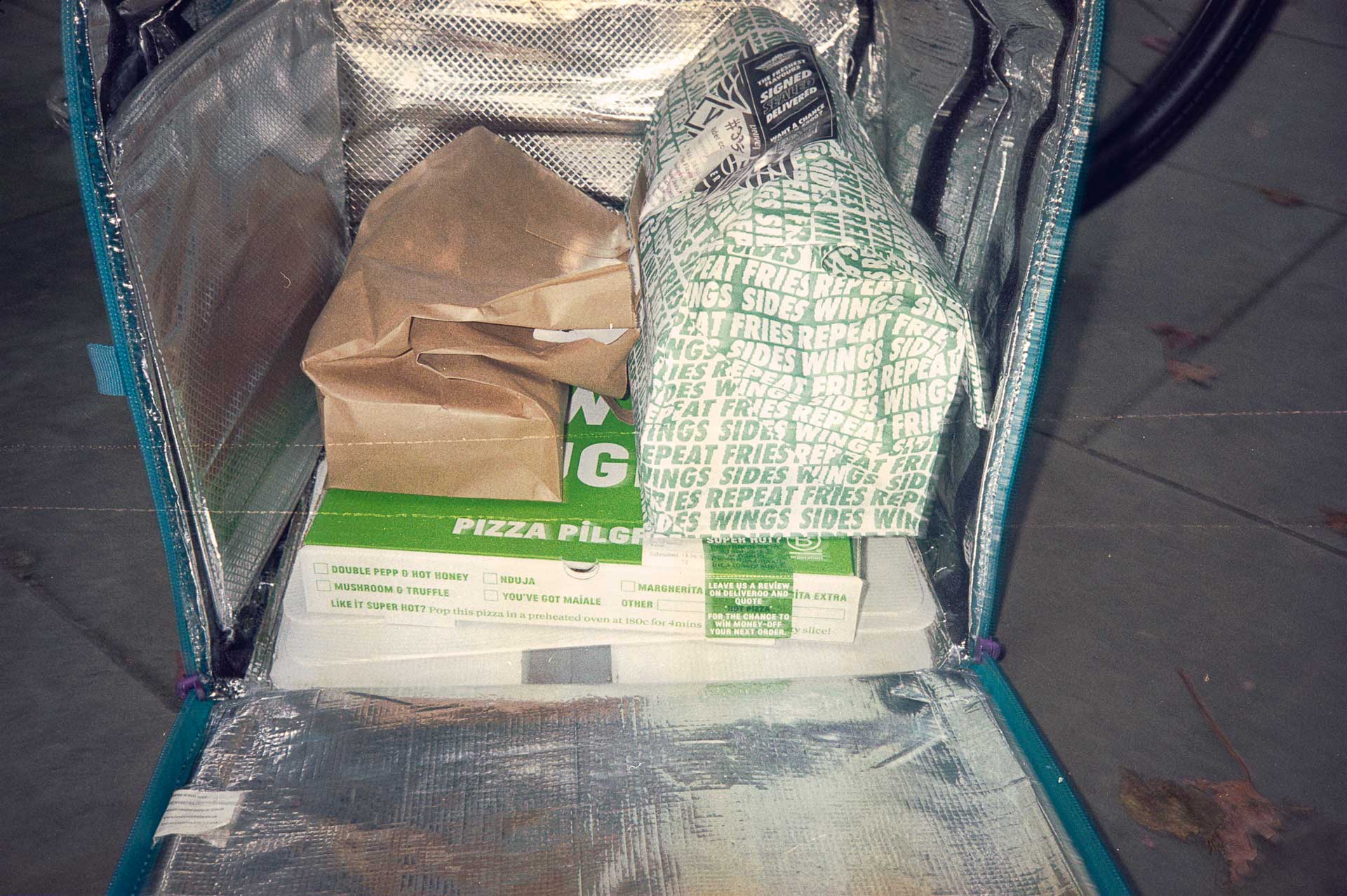

Allan Weber, My Order, 2025. Installation view, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill On Sea. Photo: Rob Harris. Courtesy of the artist.

RA: Absolutely. Spending more time around you, I saw that you’ve got a soccer team, you started a gallery in a barbershop, you’ve also got your barbershop series, and the thing with the kids stretching canvases… which is really just a ritual of people coming together to change their lives—what you called a technology of existence, right?

AW: Yeah, it’s about that flow… and it’s not really about sticking to one thing. We invent and reinvent these tools. It’s not about saving everyone—it’s about doing something, and through that doing, giving people access to something, or sparking something in them. Not everyone’s going to become an artist—and that’s okay. What we do is pretty abstract anyway.

RA: But you never know… We definitely know a bunch of people who are artists without ever being called that. Especially now, with this pressure for everyone to be productive—it’s reached the art world too. Being an artist has come to mean cranking out work, neatly packaged in series. But there’s a whole group of artists out there who are storytellers, who talk their way through things, who riff and boast.

AW: I think being an artist is about being the least “artist” you can be. Sometimes it’s not even about art—it’s about survival. It’s about being an artist in life.

RA: It’s that mindset you mentioned before—that fire in the eyes. Like graffiti, for example.

AW: Yes, and it’s also about the story we tell… The favela isn’t just the bad stuff the media shows. It’s not just about drugs—the neighborhood is a cultural expression of a place. It’s the deep-rooted culture of Brazil.

RA: Totally. And in those places that are shown as exceptions to the chaos—those “cleaner” areas—people are dealing with another kind of pain. Like the pain of loneliness, of people not connecting with anyone or anything… You go all the way to the middle of England to talk about community technology because people there are craving that.

AW: They don’t know it.

RA: And then you show up, full of joy, talking about the things you love, and to them, it seems impossible to live in a place like that. And you’re like: not only is it possible, but I’m happy as hell. Sure, there’s bullshit—there always is—but that’s true everywhere. And I think what we have in common, even coming from different places and contexts, is this need to move, to circulate.

AW: Yeah. Like the baile [funk party], for example—it’s powerful because it’s a workers’ party, it’s a moment to have fun. The crew doesn’t have the means to enjoy stuff in the South Zone. But in the favela, there’s a baile, it’s a moment of leisure. Everyone you know is there, there’s no entry fee, the beer’s cheap. It’s our party. There’s even a quote from Luiz Antônio [Simas]: “We don’t play and celebrate because life is easy. We throw parties because life is hard.”

RA: I think we can end on that, because that quote hits hard, right? And it says everything about your last two works. We’re making art because life is hard. We do this because it’s a place of refuge.

AW: Refuge, that’s it! Thanks so much, Raoni.

RA: Thanks, Allan!

Valentina Tong, Cariri, 2021 Cortesia da artista.

Valentina Tong, Cariri, 2021 Cortesia da artista.

To learn more about Allan Weber: @tremdaarte5b

To learn more about Raoni Azevedo @raoniazevedo

Valentina Tong, Cariri, 2021 Cortesia da artista.