Chiara Banfi: Shall we?

Gustavo Prado: Let’s do it! Should we start by thanking our host?

We’re talking today at the invitation of Art Dialogues, from our dear friend Anita [Goes], who’s over in New York publishing this beautiful magazine. I’m here in Rio [de Janeiro], and you’re currently in Italy.

CB: Yes, visiting family.

GP: And this conversation came about kind of as a way of reconnecting. We hadn’t seen each other in over 20 years, right?

CB: That’s right. Since Rumos [Itaú Cultural’s visual arts program]. The beginning of our careers and the start of our journeys in art.

GP: It’s a beautiful thing to spend so many years apart and still find traces of the person you once knew in the work they’re creating today. And to slowly discover how that work connects to everything they’ve thought and lived over time. In this conversation, we’ll have the chance to dig into that. I was already curious about your work back in the Rumos days, and I’d love to hear more about what happened during the years we lost touch—especially about what you’re exploring now, in this current phase that’s led to such striking pieces. But my first question is about your hands.

Even back then, your work had a strong spatial and architectural presence—like that incredible piece you made on the façade of the Fondation Cartier in France, or at Instituto Tomie Ohtake in São Paulo. You were working at a large scale, but always kept the memory of your hands in the work, as if your drawings were your hands moving through space. And after a long stretch working with production methods that relied on others—like luthiers crafting your instruments or factories pressing vinyl—it feels like you’re now diving back into the physical presence of your own body. Would you say that’s true?

CB: It’s funny, back in the phase when I used scissors to make those wall drawings, I got tendinitis. And now I have tendinitis again. But in the beginning, when I was doing those cutout works, my desire was to draw sound visually as it moved through space. I wanted to try and translate how sound occupies a space.

GP: The acoustics of a space.

CB: Exactly. When I was in college, I used to make little sounds against the wall, really close up.

GP: At FAAP [Fundação Armando Álvares Penteado]? What kind of sounds?

CB: Yeah, I even did a performance there. It was a kind of sound exploration—not melodic at all. I was trying to carry sound into different parts of my body, and then take it outside my body into the architectural space.

GP: Do you remember what those sounds were like?

CB: Totally! At the time, I was taking classes with Madalena Bernardes, an incredible singer from São Paulo. And her classes were wild because you’d try to make the sound spiral, then send it down to your pinky toe, or imagine the sound moving behind your throat, or your brain sending it forward to the front of your forehead. They were exercises in sound projection. It was a really cool exploration.

GP: So the sound was moving through the body?

CB: Yes, through the physical body and also the energetic field. She’d say: if you want the sound to reach the end of the room, send it behind your throat, have it travel behind your skull, and release it from the top of your head. And when you visualize sound this way, the reach becomes much greater. I’d play with the architecture of the space, doing exercises. And the idea was for the exercise to be continuous, uninterrupted, really focused on fluidity.

Chiara Banfi, J’en Rêve Fondation Cartier, Paris, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: But when you describe making a sound against the wall in the studio, does that mean you would go up close to certain parts of the studio?

CB: No, I didn’t even have a studio or a proper workspace back then. What I needed were walls. I probably seemed like the crazy wall lady—I’d show up at friends’ houses with a vinyl in my bag and ask, “Can I try it here?” This was right at the beginning of my relationship with Vermelho [Gallery]. I’d go there just to do sound exercises in the kitchen, way before any exhibition was even planned. The work would travel through the space—it would rise, hit the ceiling, and then Edu [Brandão] told me to see where it reemerged. Turns out it came through in the library. So I created an entire piece there. The sound descended again, and that’s how I gradually started to occupy the edges of the gallery.

GP:And before you had any walls—what then?

CB: I was working in sketchbooks.

GP: It’s interesting how you bring the presence of the other back into the conversation. When I think about manual work—like cutting—I imagine a solitary act. But the other is there too, especially when you’re negotiating the spaces where your work will take shape. That idea of singing close to walls and imagining how sound moves through space reminded me of exercises Matthew Barney used to do in his studio, where he built gym-like apparatuses to make drawings. He’d jump on a trampoline and try to guide his pencil to the far corners of the room. In your case, it’s as if sound is your pencil—your voice draws the line, and the scissors follow its path.

CB: Yeah, the sounds I made were more exploratory than melodic—more like an investigation into the sonic possibilities of the voice, without it necessarily forming a song, you know?

GP: Beyond what we might expect from an artist working with installation—looking at a space and thinking about what kind of intervention could shift the viewer’s experience—your process seemed to involve listening to the space before visually occupying it?

CB: Maybe even more than that. There was definitely a kind of listening, but I think it felt more like a response. When I made a sound, I was waiting for something in return—a kind of exchange between the sonic expression and the space’s reaction. That was a time when I’d walk around school and never stop singing—it was wild [laughs]. I was constantly making sound, and I think drawing became a way to organize that sonic field, to translate it into the visual.

GP: It’s like you were making it last a little longer.

CB: Exactly.

GP: Even though the adhesive vinyls often remain in the space, there’s still something temporary about them. You were talking about that intervention at Vermelho Gallery. It lasted for a while, but then it was taken down, right?

CB: Yes, but it stayed up for a few months.Not the intervention that was part of the exhibition, but the one in the library remained for quite a while. It was wonderful because since the work was made of adhesive vinyl—which is perishable—so it felt less daunting. I knew it wouldn’t last forever; there was a sense of fluidity to it. It was like a sketchbook. Sometimes it was just a small fragment—a bathroom, a windowpane, or a piece of glass. The color came through the windows, layered and made vibrant by the light’s transparency. There was always a connection to nature as well. I think it was an interweaving of nature, song, and music. The colors entered the space like landscaping or a garden.

Chiara Banfi, Viga Mestra, 2004. Adhesive vinyl and wood on wall, variable dimension. First solo show at Vermelho. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: It really does have a plant-like quality.

CB: Yeah, it feels like a vine.

GP: And if you tried to translate it into music, it would be almost impossible, right? Because it’s like an uninterrupted sound that keeps interweaving with others. Trying to recreate that with a clarinet, for instance—no lungs could handle it [laughs].

CB: Yeah, you’d need the pauses [laughs]!

GP: Silence starts to play a more present role in your work too. But this memory of organic forms… At that time, were you already consciously thinking about nature, or was it only while making the work that you realized the connection?

CB: I think it came along with it. Especially because the first vinyls I used were those really cheap ones that imitate wood grain—the kind people used to line drawers. So the desire for a wood texture was already there. In fact, there was a time when I photographed textures—usually water or leaves—and printed them on adhesive photo paper. That also became part of some installations.

GP: Parallel to the vinyl series?

CB: Together. I was doing the vinyl pieces, and then I had what I called “explosions”—moments where there was an excess—and those moments also included the textures. Sometimes it was a series of water photos or plant textures.

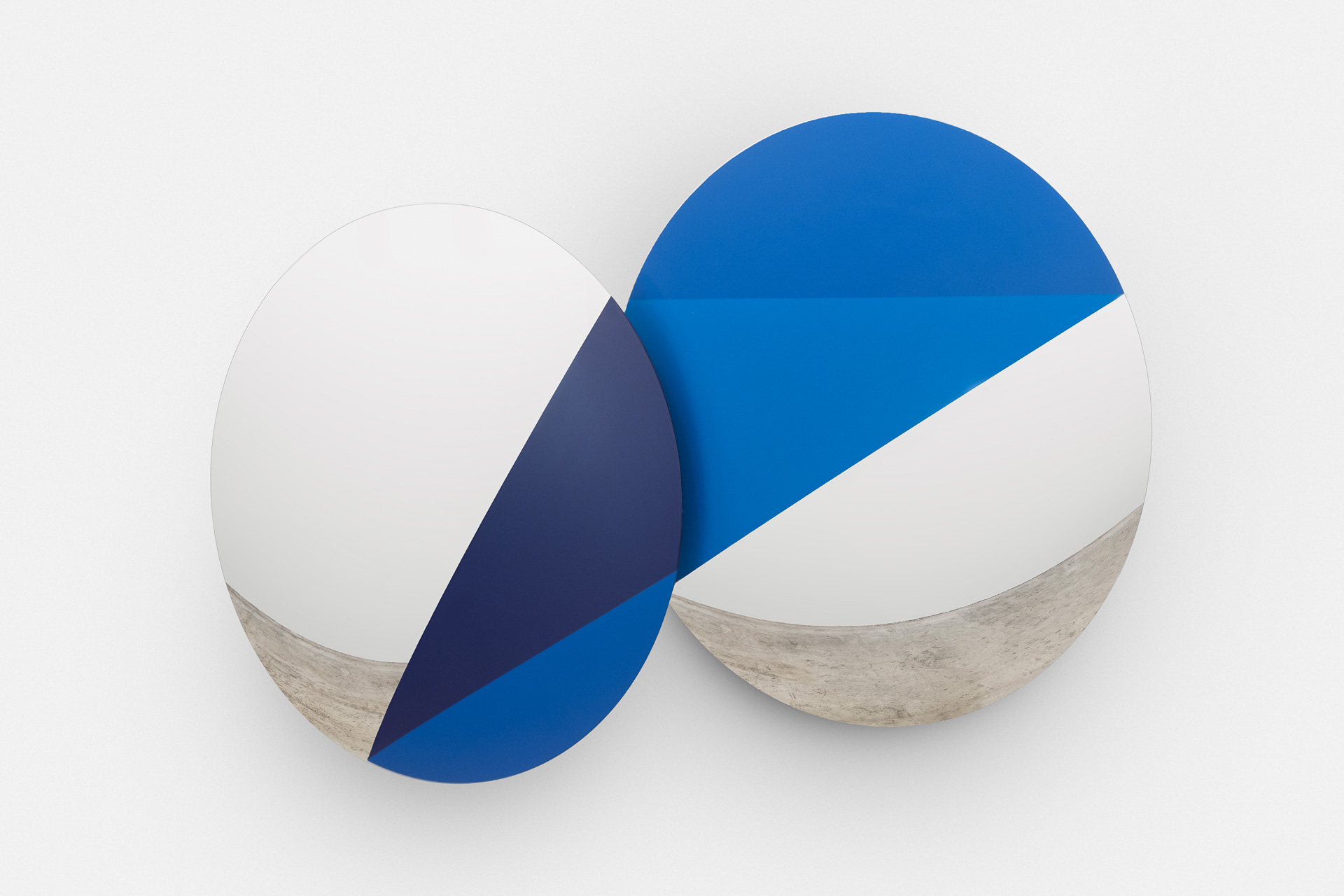

GP: Interesting. The sense I get is that after that, there’s a dramatic shift into a more urban, almost technological cultural field. I mean, the instruments, the records—even the design of it all.

CB: That happened a lot because of the studio environment, when I moved to Rio de Janeiro. I didn’t have a studio for a long time, so I spent a lot of time in my ex-partner’s studio, surrounded by instruments and analog equipment. The old instruments—and all those music-related tools and objects—were so beautiful. There was an aesthetic care in those technical objects. So, for example, in the Sunburst series [2012], I would just look at all those instruments lined up, each one with its own paint, its own choices…

GP: Are you talking about the backs of the instruments or the part with the strings?

CB: Both parts. Because the sunburst [a style of finish on musical instruments] has a certain kitsch vibe with that gradient from black to orange to yellow.

GP: Sunburst is a way of painting the wood on the instrument?

CB: Exactly. The oldest sunburst, if I’m not mistaken, was a silverburst with a gradient from black to gray, on a 1940s Rickenbacker… absolutely beautiful. There’s always this care so that you can see the wood grain. And usually it’s done with woods from the Northern Hemisphere because they tolerate temperature changes better. The instrument relates to our body: body, arm, hand. So, in my Sunburst series, I gradually removed all the details to leave only the body. This finish style uses a glossy lacquer, and I worked with the proportion of the body so that we could see ourselves reflected in the instrument’s paint, as if they were portals. I think I did around 33 paintings. Some are classic, others I discovered along the way during the research. It was a really cool process. I worked with Celso, who painted instruments for a luthier in Rio. He worked on an area about 30 centimeters, and I expanded that to relate to our body, so we set up a booth for him and he developed the technique to create a larger field and such. But really, like you said, I moved from a much more organic and abstract relationship to one much more industrial, focused on what makes sound.

Chiara Banfi, Les Paul, the Sunburst Series, 2012/13. Ash wood, PU paint, lacquer, 63 × 43.3 × 2.75 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: There’s a beautiful text by Nicolas Bourriaud where he talks about art as a post-production exercise, and it’s really interesting how your work aligns with that idea in this phase—dealing with the memory we have of certain cultural elements and then recombining or relocating them. You take the visuality of the music field, its more material aspect, and transfer it to the art field. It’s the scale of a painting with the language and wood of sunburst. So post-production as editing, which is equivalent to sampling or video editing or adding special effects. You’re working with a repertoire people already know, so the artist’s role is to make new combinations, not to reveal something from scratch. It’s not such a radical leap. It’s more about new associations that haven’t yet been made. I feel like you’re in search of these associations, often juxtaposing and combining somewhat contradictory things. Just like there’s a contradiction in taking a cut vinyl—something made from petroleum, plastic—and making a plant out of it. Or trying to make something very ephemeral, like sound, last a little longer. You trace with your eyes the path a plant would take to grow in that place. And there’s a clash of times in this, right? I find it very powerful when you start combining stones with strings precisely for that reason.

CB: That was really cool. At that time, I was researching synthesizers, starting with the older ones. My dad’s cousin who was an assistant to Don Buchla in Berkeley, who created synthesizers around the same time as Moog. I think these objects are beautiful… some were huge, with cables connecting one to another allowing creation of sounds and textures. With synthesizers, I think a bit of harshness entered, it’s not that melodic thing… you could even draw a parallel with the sounds of planets NASA makes available. Have you heard that?

GP: No!

CB: It’s wild! The sound of Saturn… wow. And Venus is incredible. NASA captures those sounds and translates them into something we can actually hear, since we naturally can’t perceive those frequencies. I feel like synthesizers are a bit like that—they resemble the kind of noise the universe makes. I started getting into stones while researching turntables, because the needle contains a piece of crystal. These days, it’s made synthetically, but originally it was quartz. We often think we’re moving away from nature, but even in the most advanced technologies—things that seem to disconnect us from time or the natural world—you’ll find materials that come from nature.

In my early works with cables and stones, I used quartz connected to an RCA cable—the same kind used for synthesizers. That’s when silence started to play a role, because even though the stone emitted sound, it was inaudible. Everything has a sound, since everything has a frequency, and there are scientific ways to extract or measure the sound an object might make. So I began connecting stones that would never meet in nature—like pairing a quartz from Bahia with obsidian, a volcanic rock from Mexico. When lava hits water, it hardens and becomes something like glass. Those combinations created what I call silent conversations—silent for us, at least. But the intention was always to generate a kind of dialogue, a song, a poem.

GP: I don’t think Bourriaud would take that into account. He always speaks about associations formed within the cultural sphere, about a kind of memory we carry of things made by people. But you’re talking about communication between stones—an association between elements of nature themselves. Of course, it takes a person to imagine that connection, but envisioning the possibility of a dialogue between stones… I think that’s very much what art is about: expanding or imagining an experience we haven’t yet had access to. What does a sound I can’t hear actually sound like? At the same time, you’re drawing on our memory of certain equipment. You’re using a cable—like the kind you’d use to plug a guitar into an amp, right?

CB: I used that cable a lot, the P10, but in the beginning I used RCA more, which is what you use with synthesizers. There was a piece called A Escala de Mohs (The Mohs Scale), 2015, which refers to the scale used to measure the hardness of stones—from the softest, like chalk, to the hardest, which is diamond. It’s a scale of resistance, of durability. I worked with different types of quartz, from the lightest—this sort of translucent clear one—to the darkest black quartz, plugging one into the other. That’s a piece I really love. And in this case, I wasn’t working with a scale of hardness, but of color.

Chiara Banfi, Escala de Mohs, 2015. Imbuia wood, quartz crystals and RCA cables, 63 × 118 × 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: Is there a recurring interest in cataloging or classifying in your work? You use frames, grids—these structuring devices that feel like tools for organization. Even in that piece with the stone and the black marks… when I first saw the images, I assumed those were your interventions. But that geometry, that graphic precision—it’s already there in the stone. It comes from nature. It’s incredible.

CB: We tend to think that precision is a human trait, but there are so many straight lines in nature. It’s bizarre. There’s a stone called pyrite cube that’s a perfect cube, with 90-degree angles. It’s incredible. When I found those lines in black tourmaline embedded in white quartz, I was amazed. That’s when I got into stone hunting. I don’t know how to read sheet music, but the symbol for a rest is just a black mark. When I saw those stones in a shop, that’s all I could see—a rest. It’s the symbol of that moment of silence that builds the entire possibility of music. I saw nature creating that, you know?

GP: So good. And there’s definitely that drive to find some kind of order behind something that appears more intuitive, right? The vinyl cutout finds architecture, which is geometry. The stones are arranged on the wall like a grid. The collecting and cataloging of records, the transitions of color between records, the collection of sleeves that relate to each other…

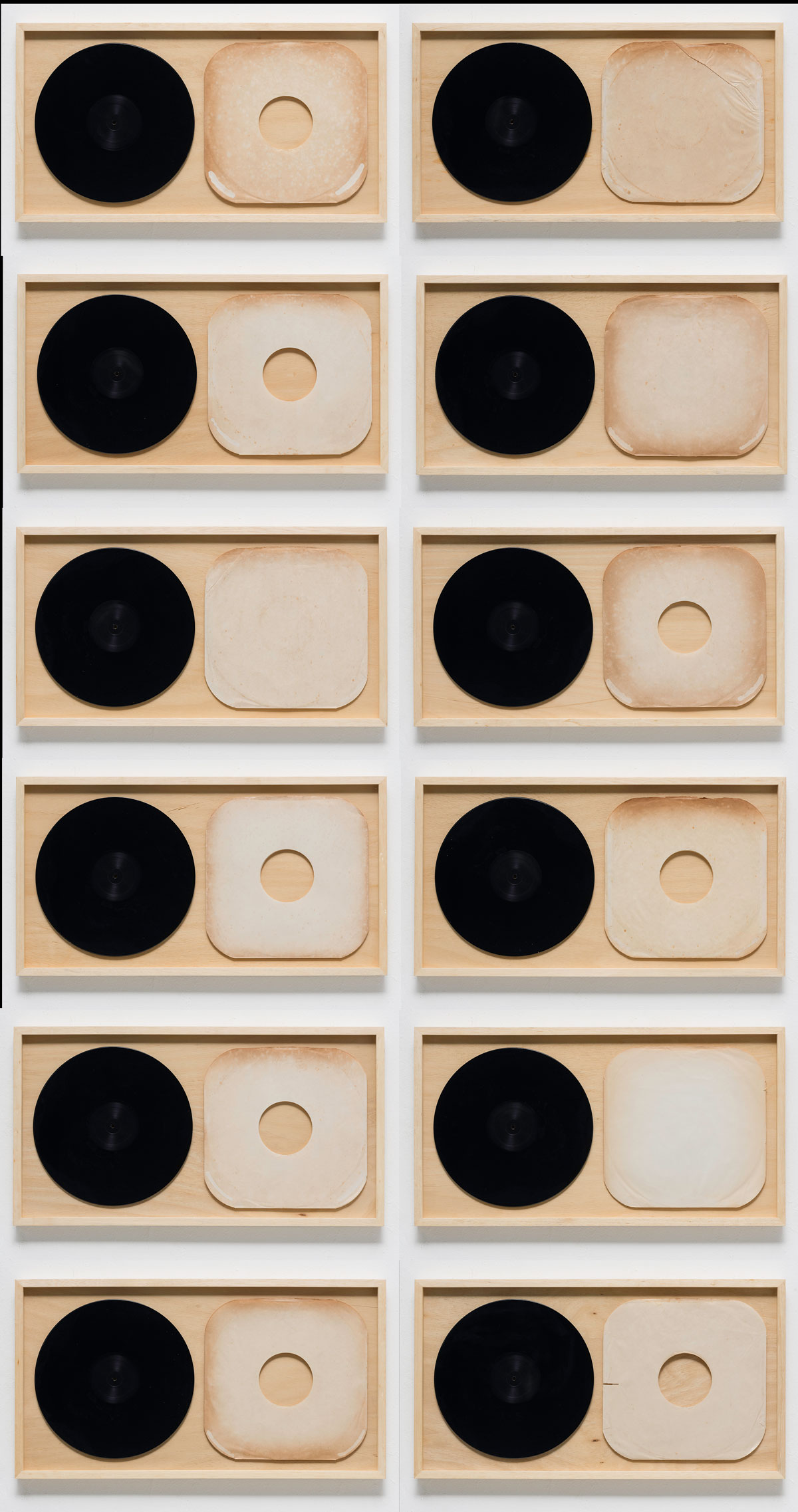

CB: There is a real interest in organization. The record sleeves thing was curious. I spent a year or so collecting those sleeves. I organized Kassin’s [Kamal] collection, and every record had a sleeve that—whether blank or filled with information about the industry—was never about the artist. Some were really cool, with instructions telling you to send the same sleeve back to the label like in a raffle, and if you were selected, you’d win a limousine ride while listening to records [laughs].

GP: That’s amazing [laughs].

CB: I found two of those. And then when I did that piece at Edu [Brandão] and Jan’s [Fjeld] house, I found two sleeves with drawings by [José] Leonilson, with Leonilson’s handwriting. One phrase was “No No Yes Please”, which became the title of my exhibition. And imagine, these were records that had just been stored away. So there was a real exchange with the people who had these collections. When I did that piece, around 2010 or 2011, and started this digging process, the old sleeves had already yellowed—so there was this mark of time. At that point, vinyl was still out of fashion, it hadn’t made a comeback yet. I even found a factory in the U.S. where I could press a 180-gram LP really cheaply and there was no waitlist. When I tried to do it again in 2013, there was already a waitlist. So I caught the beginning of the vinyl revival. Anyway, I ended up with around 300 or 400 sleeves, and that was the fun part of the cataloging. Since most of the collections were in Brazil, I could see which record labels gained traction at certain times and how there used to be this industrial support that has since disappeared.

GP: The history of that industry in Brazil.

CB: Yes! And the person who wrote the text for my exhibition at Silvia Cintra [Gallery] was André Midani.

GP: Oh, how amazing!

CB: Actually, he wrote me a letter—a beautiful thing. When he came to Brazil, he started a label called Imperial. And I found two Imperial records with the original sticker and made a diptych for him.

Chiara Banfi, Discos Vazios, 2012. 83 × 55 inches [each]. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: Talking about your encounter with Midani, Kassin’s collection, and you’ve mentioned Edu [Brandão] many times… and also, hearing you talk about the record-making process as a memory that’s disappearing—it makes me think there’s also an effort on your part to preserve, to make things endure, or at least to confront what lasts with what fades and is impermanent. I’m also reminded of the story about the recording of Aquarela do Brasil by Elza [Soares], which you witnessed. I’d love for you to share a bit of that story and the work that came from it.

CB: Oh, that was such a gift! Gilles Peterson came to Brazil to record an album of Brazilian music with Kassin, and I was lucky enough to witness Elza recording Aquarela do Brasil in 2012, at Companhia dos Técnicos—a legendary studio in Rio. It was unforgettable. She did three takes, and on the last one, her voice broke slightly. There was a real vulnerability—she even shed a few tears.

GP: That take didn’t make it onto the final album, did it?

CB: Right, I knew that take wouldn’t be used. At that stage, it was just her voice with a basic guitar track—Gilles planned to build the full arrangement later. So I begged him to let me have that take. And then I started thinking about all those moments in the studio—those takes where artists go slightly off-pitch or make a “mistake” that actually reveals something deeply vulnerable or emotional… moments that no one ever hears, that just sit archived on a producer’s hard drive. I asked for that track because I wanted to create something using just her a cappella voice, but the guitar had bled into the vocal mic, so isolating her voice wasn’t possible at the time. The technology just wasn’t there yet, so I shelved the project.

Then during the pandemic, Kassin was working on Wilson das Neves’ album—he had just passed away—and he used a plugin that could clean up the voice. It was literally the press of a button. And the moment I saw that, I thought of Elza’s track.

GP: So you finally found a way to separate the guitar from the vocal recording.

CB: Yes! I cleaned up the track, and it turned out beautifully. Then I called Gilles to ask for his permission and sent it to Elza so she could approve the use of her voice. She loved the concept, and I went through the entire process of producing a record from scratch.

GP: She loved the idea of a work that preserved her getting emotional, with her voice breaking.

CB: Exactly! She understood.

During the pandemic, I was living in the mountains in Rio de Janeiro, and a friend of mine, Pepê, has a record factory in Petrópolis—Rocinante. He was amazing and let me use the factory for a day and even saved a bunch of vinyl scraps for me, sorted by color. So I made a record: one side featured Elza’s voice, and the other side was blank. When the transparent disc came out hot from the press, I was melting the scraps in a little oven and working the colors in by hand. I had about seven seconds to add the color before the press closed. I made an edition of 100 records, each one with a unique, hand-melted composition—like a watercolor painting.

The piece was called Elza, and the exhibition was titled Take Three, because it was her third take from that recording session. Elza passed away the day after the records were produced. When I left the factory, I called her producer, but he didn’t answer. The next morning, Edu called to tell me she had just passed. She never got to see the finished piece.

GP: Wow… that’s something. Did someone in her family keep a copy?

CB: Vanessa [Soares, Elza’s granddaughter]. I still need to give it to her—we’re planning to meet. She came to my exhibition in Rio.

Left image: Chiara Banfi, Elza, Take 3, 2023. Installation at Vermelho Gallery. Right image: Chiara Banfi, Elza, A record in the box, 2023.

Wooden box with acrylic lid and a vinyl record, 14.5 × 19 × 2.7 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: As is typical in your work, you also found a way to frame the record, right?

CB: Yes, I made an acrylic box with a wooden base, sized like a turntable, so you can position the record inside. It works both on the wall and on a table, and you can open the lid whenever you want to play it. The record is very crackled because the temperature of the base disc wasn’t exactly the same as the color elements, so there are bubbles, and it has that nice, dusty old-record sound, you know?

GP: With the imperfections of the recording itself. And bringing the conversation to your current moment, it seems like you’re stepping away a bit from those collaborations. You’ve always had—and still have—a beautiful quality that, in Zen, is called beginner’s mind… being the curious artist rather than the expert, engaging with people who have specialized knowledge. When you’re the curious learner, the possibilities are wide open. When you become the expert, they start to narrow.

From what I can tell, lately you’ve been diving even deeper into learning, into discovery. You’ve returned to emphasizing the gesture of your own hands, and like I said at the beginning, I feel like you’re stepping back a bit from that dialogue with specialists—the singer, the record maker, the luthier. It feels like there’s a deeper conversation with yourself now.

CB: Yes.

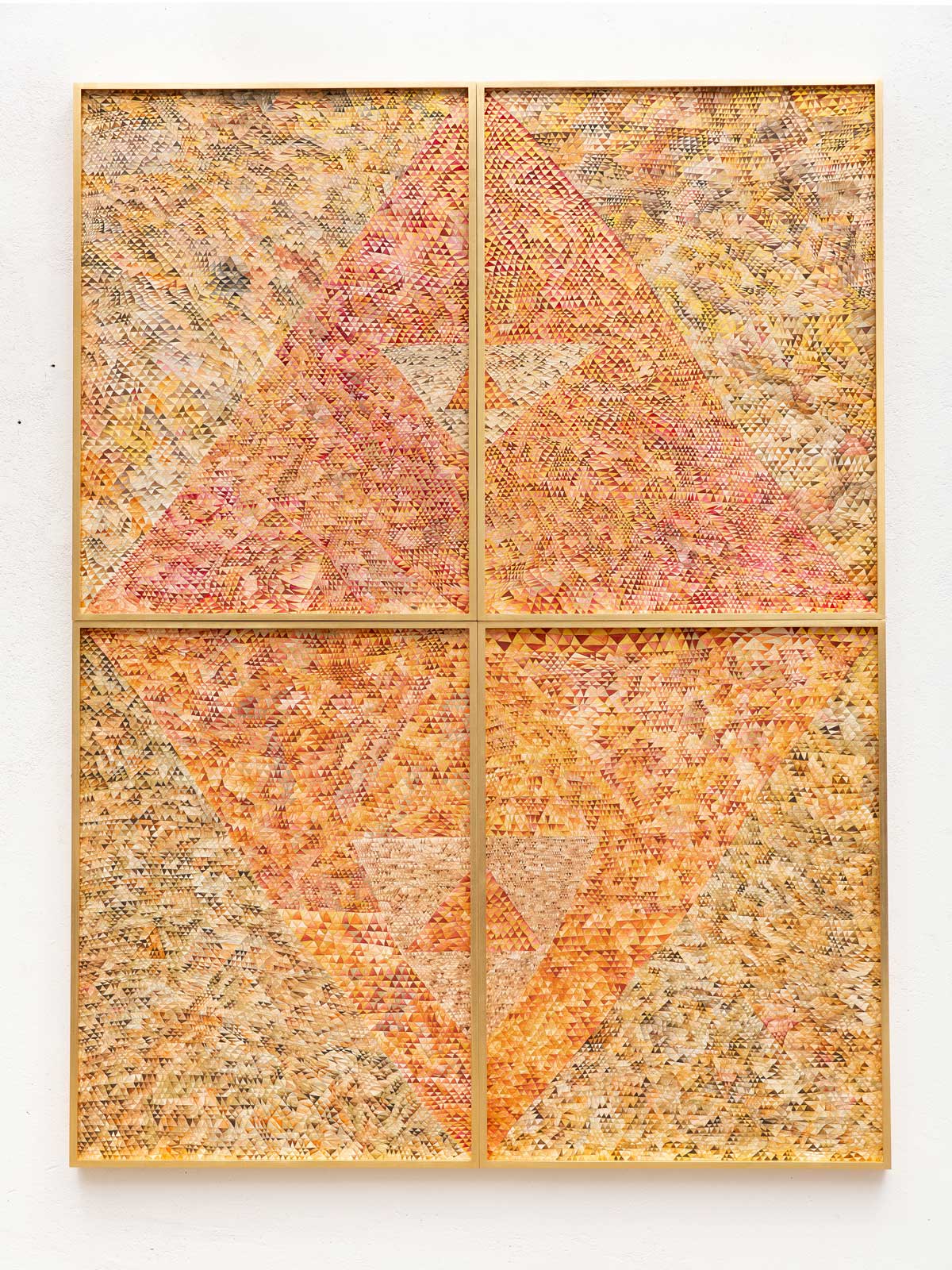

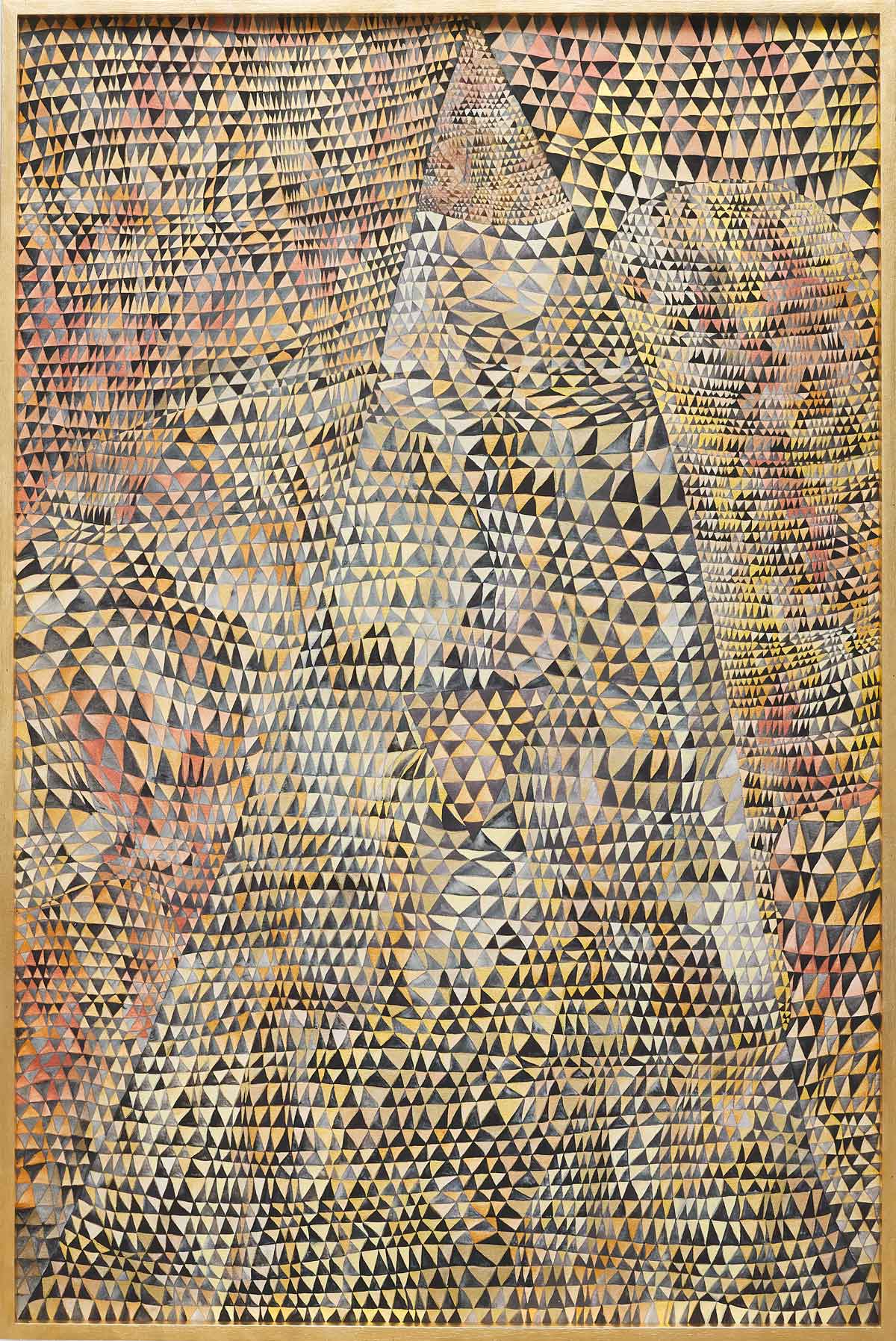

GP: You’re building these massive images—webs or networks that, once filled in, form triangles—and alongside that, you’ve been working on a series of water videos. What’s crazy is that the videos reveal a kind of geometry within water. It’s like water takes on geometric patterns when it vibrates, funnels, or goes through states of tension. So now you’re creating these large-scale watercolors, and I’d love to hear a bit about how that work emerged. How did it begin? What is this new phase about?

CB: The phases I go through remind me of what I used to do with the wall vinyls—sometimes things get really narrow, small, contained, and then there are moments when everything opens up and expands. When things narrow, that’s when I turn to my notebooks.

GP: The same notebooks from way back?

CB: I’ve had notebooks in every phase. It’s like narrowing my field of vision a bit and turning inward—maybe as a way to get reorganized inside, I’m not sure. When I started working on these watercolors, I began studying geometry. Music is extremely mathematical, and of course, so is geometry. And I found myself wanting to create the forms of sacred geometry, but to do that, you need precise constructions to develop the more complex shapes. I didn’t want to go down the path of rulers and precision—I stayed with the form. The triangle is the first shape in geometry, so I started working with it in my notebook. It was new for me, but there was a desire for repetition. And from the moment you repeat something, there’s rhythm. And if there’s rhythm, there’s melody, there’s music. I think it was another way for me to translate a sonic field into a visual form. Especially when you bring in color. I feel like, as you said, this work moves away from the more industrialized aspects of music or things directly related to music-making, but at the same time, it feels like a more direct conversation with the adhesive vinyl—it’s abstraction. A gesture that generates melody.

Chiara Banfi, Triads series, 2025. Watercolor on 100% cotton paper, 94.5 × 63 in. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: How long ago did you start this new work?

CB: About a year and a half ago. And I think the grid has to do with a need to reorganize, which also reflects what’s going on in my life. It’s a restart. A new beginning, building a new setup, a new grid.

GP: And maybe there’s a kind of shift in your central field of research or interest—moving from the realm of culture to the realm of spirituality. An investigation into things that are hard to see but nonetheless present, like we talked about with the sound of stones. In Zen Buddhism, they talk about the sound of one hand clapping.

CB: That’s beautiful! When I meditate and manage to go deep, triangles start appearing to me. And they’re not static. It’s like a moving grid of triangles—sometimes they’re larger, sometimes smaller. It’s highly visual. And it’s always the triangle.

GP: That’s a visualization experience that arises in a stage of meditation. Should we talk about that a bit? Because that connects to abstraction. Many artists have found abstraction to be a channel for communicating with another plane of existence. Take [Carl] Jung, for example—he went through a similar experience creating mandalas during a personal transformation, making and unmaking them as a way to reorganize himself.

CB: I think it’s very much like that, yes.

GP: We’ve been discussing Hilma af Klint extensively—truly a pioneer of abstraction—and how she perceived the forms that appeared to her, those mandala-like shapes, as a kind of mediumistic experience. As if she were receiving messages. This also exists in music. We often talk about [Gilberto] Gil, but seldom discuss the spiritual dimension of his experience and how deeply it permeates his music, lyrics, and his very being. It’s something somewhat private or even secretive in an artist’s life, yet profoundly present. Think of Louise Bourgeois or Kandinsky… How do you see your journey in this new work, especially considering your own spiritual experience?

CB: I feel that in many instances, across different series and phases, whenever I brought in the idea of silence, it came from a desire to break away from an internal dialogue. That’s what meditation is for me: a practice where thoughts move into the background and something else comes to the foreground of the mental screen. And that “something” appears to me as visual geometry—a universe of intense color and another kind of beauty. I feel like I can reach these places not only through meditation, but through repetition as well. That’s why the triangle paintings started in my notebook. The triangles are still there, and now they’ve become grids, something bigger, because the repetition of the practice induces a kind of trance state that opens a channel to another field of information.

GP: And you’ve been calling these works Portais [Portals], right?

CB: Yes, I call the large ones Portais. I’ve been making connections with artists and historical figures who engaged with this other realm—people like Walter Russell, who is absolutely fascinating, Nikola Tesla, and Hilma af Klint. They weren’t truly understood in their own time. There simply wasn’t room for them to share that kind of knowledge because science has always demanded precision and objective truth. Rationality insists on evidence. But there’s another realm of information that reaches you differently—you sense it—and you can access it once you quiet everything else. When you begin to soften that rational, fact-driven part of yourself, you open the door to an entirely different universe.

GP: That’s what Gil would call the mystery. “Mistério sempre há de pintar por aí” [“Mystery is bound to show up around here”].

CB: Yes [laughs].

Chiara Banfi, Eternal Instant from the Portais [Portals] series, 2025. Watercolor on cotton paper, 47.2 inches × 31.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

GP: It’s funny because, thanks in part to the legacy of Nise da Silveira—a deeply influential figure in Brazilian imagination, art, and psychoanalysis—there’s an acceptance of the idea that images are a way to access the unconscious, and that they come from within. But the idea that they might come from outside still feels like a huge taboo.

CB: Especially because it’s an outside that’s actually inside—but one you can only reach by going within.

GP: But this clash is the very exercise of art because you depend on a present body acting upon a present material—a water that dries on paper, a pigment that builds a color—to have a transcendental experience. It’s a desire to look from outside at something that’s inside, right?

CB: Or to translate it.

GP: It’s like trying to see an emotion. I think Nise da Silveira had a powerful insight about this—how much we tend to rely on language as the primary vehicle for accessing the truth of deep experience. And here I go again, always bringing up Zen, right? [laughs] It’s just the framework and tools I’ve been working with. But there’s that teaching from a Zen master that says: don’t look at the moon, look at the finger pointing to it. And then it goes even further—don’t just look at the moon, become the moon. What does it mean to become the moon? Only poetry can get you close to that. Only art. So it’s not about painting water with triangles, or painting sacred geometry, or even illustrating an idea. It’s about becoming those things—merging with the world and finding a sense of belonging that few other experiences can offer. That’s why I think spirituality has so often needed art to get to certain places.

CB: There’s also something beautiful about watercolor itself. They say water retains memory. So when you’re painting—gesturing, moving with the water—there’s a kind of coding happening: a code carried by the color, but also by the person doing the painting. I think about that a lot while I work, especially depending on which color dominates the piece. There’s a kind of encoded field there, operating on a more abstract level, where the water that dries in the painting somehow resonates with the water in the body of the person looking at it.

GP: I think that’s a wonderful place for us to end this conversation. Thank you so much, Chiara. I’m really struck by the beauty in your work.

CB: Thank you so much! It means a lot to me.

Courtesy of the artist.

To learn more about Chiara Banfi’s work: @chiarabanfi_

To learn more about Gustavo Prado: @gustavopradostudio // gustavopradostudio.com

Chiara Banfi, sketchbook, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Hero Image: Chiara Banfi, Red Test Press – from the Albers Collection series, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.