Lu Solano: Recording… Look, we’re recording the conversation and we might already get a sonogram out of this.

Vivian Caccuri: A work might come out of it already! [laughs]

LS: If I’d known it would be this hot, I would’ve shown up in a bikini! [laughs]

VC: That’s Rio de Janeiro reality! [laughs]

LS: I was reading your bio just a bit ago. At Art in Brackets we edit bios because in the United States everything has to be very efficient, very fast, and both gallery and artist bios have to be precise and compact. Whereas in our culture we sit down here, have a coffee…

VC: Things start flowing…

LS: Even their language is built around efficiency, right?

VC: Totally. So, at Art in Brackets you adapt bios?

LS: Yeah, one of the things we do for artists and gallerists is rewrite bios, because it’s hard to get someone to care about your work if the text says nothing. I was reading yours and found it really interesting that you describe sound cultures and sound itself as materials for you—not as a direct translation, but as a cultural translation that expands everything.

VC: I like to take things that belong in one domain and throw them into another, you know?

LS: Which is still a kind of translation, isn’t it?

VC: I’m not a big fan of the word “translation” because it assumes literal understanding—it assumes comprehension as function. And sometimes, by shifting the domain, you reveal things that don’t need to be understood verbally, but sensorially. Like the sound of mosquitoes, which is universally hated, but interpreted in very different ways depending on the culture. So when I look for a sound, I’m searching for something that can be easily understood or felt without verbal language. For example, if I’m going to talk about music and religion and bring Christianity into the work, I’m not going to explain what Christianity is to most people, because most people have some memory—often muscle memory—of that religion. Same thing with Mosquito.

LS: I think the first time I saw your work was a Pagode, back in 2013. I worked with A Gentil Carioca at the New York art fair. That’s more than ten years ago now, but I remember thinking it was incredible. When I saw the screen… was it construction mesh? Or was it mosquito netting?

VC: It was a mix.

LS: And which one did you start with?

VC: The construction mesh.

LS: I thought so, but I wasn’t sure.

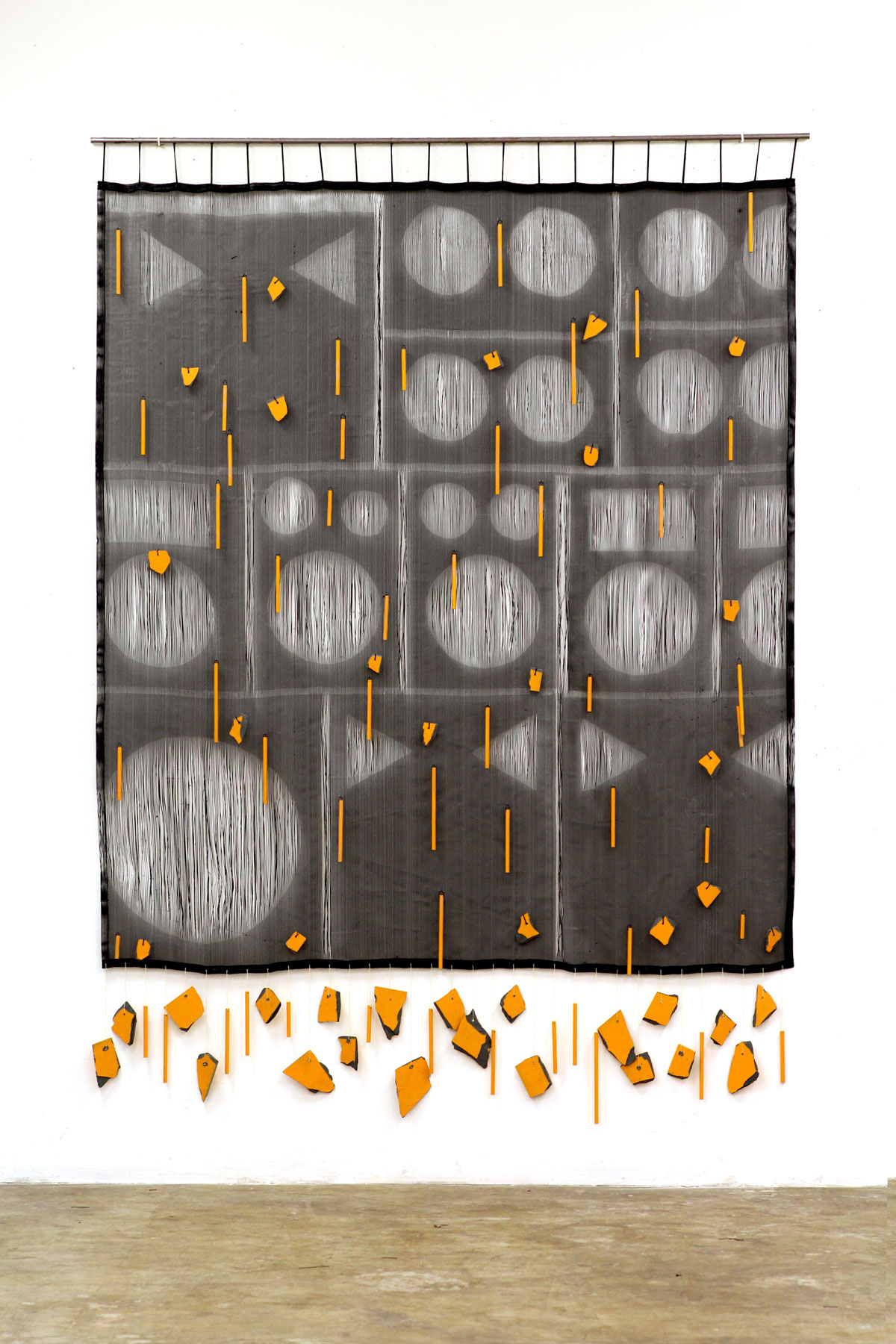

Vivian Caccuri, Fantasma Preto, 2020. Protection screen, iron bar, aluminum bars and slate, 94 1/2 x 68 7/8 x 1 1/8 inches.

Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri. Photo: Victor Rocha.

VC: Yes, it was with the construction mesh. I’ll tell you the story leading up to the meshes. I used to work with three main media: performance, sound installations, and drawings. Then, during the renovations for the Olympics and right after finishing my master’s, I think I had a burnout, because I was so immersed in text and just wanted to be hands-on. At the time, that word wasn’t used much, so I didn’t know how to name it, but I think it was a small burnout. My brain shifted frequency, and I stopped thinking visually or musically. I was thinking verbally.

LS: Because of the writing?

VC: Exactly. A year and a half of academic writing. I didn’t want that—I didn’t see myself as an academic, you know? But I wanted to do something to purge that verbal mindset. That’s what led me to create my Silent Walk, where I’d walk in silence with about 20 people, along a carefully planned route and schedule in Rio de Janeiro, so that we’d arrive without using any form of verbal communication. That performance gave me the key materials. I found the construction mesh during one of those explorations. I used to walk a lot around that area and have done many performances there. And then I found rolls and rolls of that mesh abandoned.

LS: Yes, and mesh is such an organizing material, right? Because it’s a weave, a grid. You found a grid, and that weave gave you a framework to work poetically in a non-verbal way. The grid actually functioned as a spatially lined notebook.

VC: And at that point, I didn’t even know how to draw on the mesh, so there wasn’t any narrative drawing. It was super abstract—really just for me to practice abstraction. I experimented a lot with it—cutting, fraying, folding.

LS: I remember those early ones had those frayed, deconstructed parts.

VC: At that time, I didn’t even paint on them, but now I treat the mesh works as actual paintings, because I prepare them with primer, build a structure with stitching, weights, metals, scapulas, etc.

LS: And those Pagodes have a strong connection to Brazilian culture, right? My family’s house always had some—made with string and sometimes shells. It’s a personal element, a very Brazilian household thing. I have a photo of myself at six years old, sitting in front of one of those.

VC: Me too! Me too! At the beach.

LS: [laughs] Totally. Beach house vibes! So that evoked a kind of affection for me. Even though the string is plastic, it’s a different language. But I like that it resembles something familiar while being something else entirely.

VC: Yes, it’s meant to be a strange object, to create distance so we can travel to other territories, where other sensations exist. But wait—are you Peruvian?

LS: I am. Half.

Vivian Caccuri, Caminhada Silenciosa [Silent Walk], 2012-2016. Performance. Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri. Photo: João Machado.

VC: Do you think that object exists in Peruvian culture as well?

LS: I’m sure it does. In that textile lineage and such, but my reference is really the beach house in Rio.

VC: And what’s that Rio–Peru intersection like for you? Did you ever live there?

LS: Never. My father is Peruvian. He came to Brazil to study medicine and ended up staying. I always felt a bit different from other Brazilians. In the socioeconomic circle where I lived in Rio, I always stood out because of my Indigenous features—and now that I’ve done a DNA test, I can say for sure I’m 25%. And my mother is a mix of Portuguese and Black. So wherever I went, I didn’t see anyone else who was 25% Indigenous and 20% Black. But this was never a topic at home. We were just who we were. When I realized all this about myself—even though we always preserved some of the culture—it felt a little late, you know? Not that I didn’t face prejudice here and there, but I went to a very particular school. It was the school Fernanda Torres went to, along with Chico Anysio’s kids, Dina Sfat’s daughters, Beatriz Milhazes… lots of people from the art world.

VC: What school was that?

LS: Souza Leão.

VC: Oh, how cool! Does it still exist?

LS: No, it became Espaço Educação, where my aunt was a partner. But nowadays things are too verbal, too by the book. When we define and categorize things, that’s helpful for study and learning. But it also boxes you in, right? You can end up a caricature of yourself.

VC: And I think that in the 2000s, before the popularization of decolonial and postcolonial studies—which are complex academic theories—the intellectual wave was very much focused on multiculturalism. People didn’t want to have too clearly defined traits of any particular nationality or culture. After the 2000s, belonging started to seem tacky. There was something chic and cosmopolitan about not having roots—about complete detachment, even from your own origin. For some people, something else took the place of “roots,” and I think it was the lifestyle of big cities that came in as a substitute.

LS: What happens with me too is that you don’t want to be anything “by the book.” For example, in my family no one supports a football team.

VC: Uh-huh. Being “official” is tacky [laughs].

LS: Yeah, it’s tacky [laughs]. I don’t want to diminish those who have a team, but I think the one who plays better should win. I want to be able to root for the group that’s putting on a show! But back to your work. We’re living in a time where textiles are really strong in art, right? I think the cherry on top of this moment is the Olga de Amaral exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. There was a whole group of women like Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Cecilia Vicuña… But their work is about the weave in the sense of something emerging from nothing and becoming something — and your work goes from something to nothing.

VC: Maybe from something to something else. I watched an interview with the American artist Tauba Auerbach and I really liked it. In the interview, she says she tries to balance between speed and the extended time some things require. I choose my medium thinking about something in the middle. It’s not too fast, but it gives me back a certain energy while I’m creating. And music and sound are very much like that. So I was searching for a medium that would hit the same sweet spot that sound has for me — one that also points to a kind of impossibility, to a metaphor for the invisible. And when I saw that translucent mesh, it seemed full of possibilities. For example, I wouldn’t need to weave it from scratch. And it’s resistant, it can take a beating, you know?

LS: Resilient [laughs].

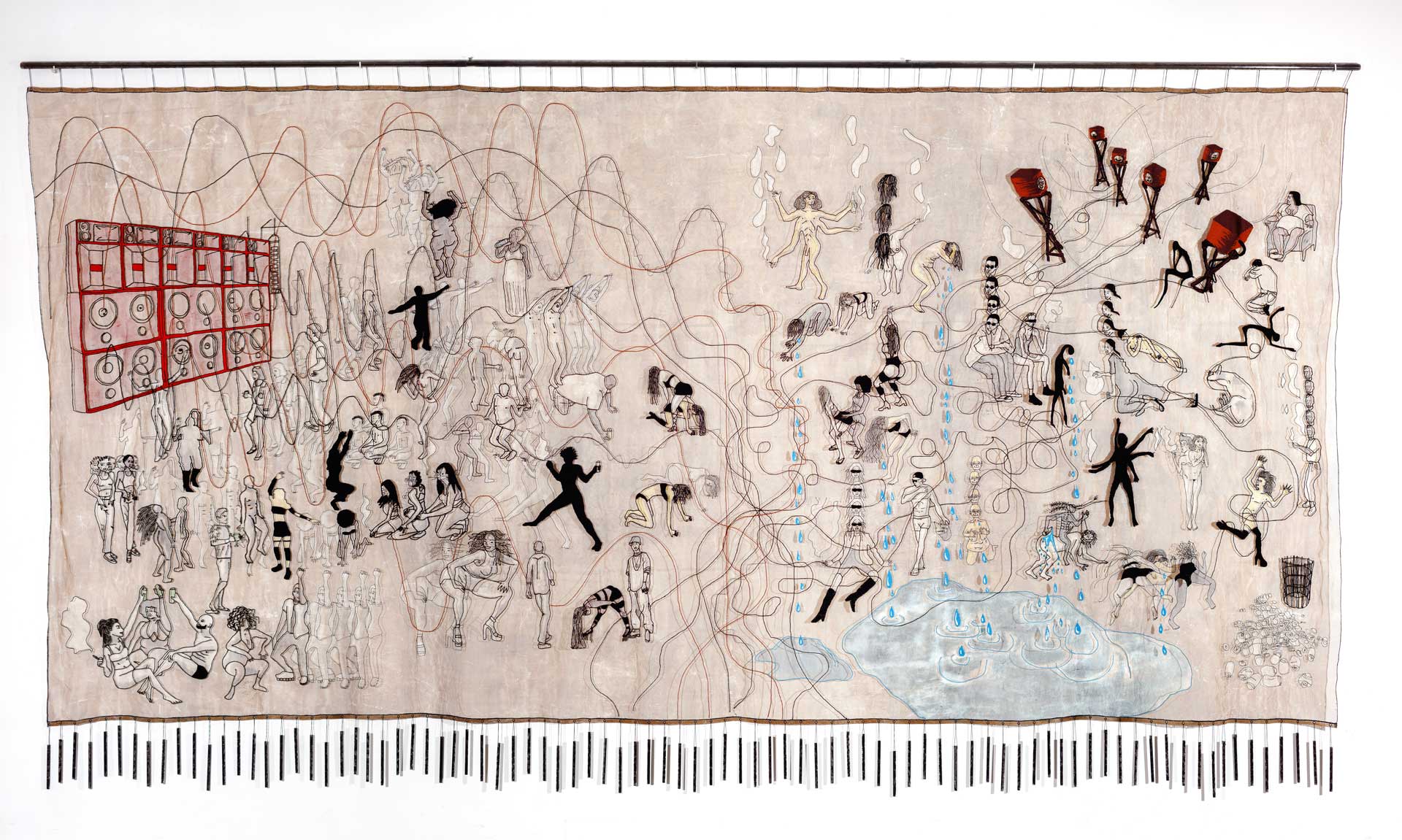

111.4 x 198.8 x 1.2 inches. Installed dimensions: 96.5 x 198.8 x 75.2 in. Courtesy of Galeria Municipal do Porto. Photo: Dinis Santos.

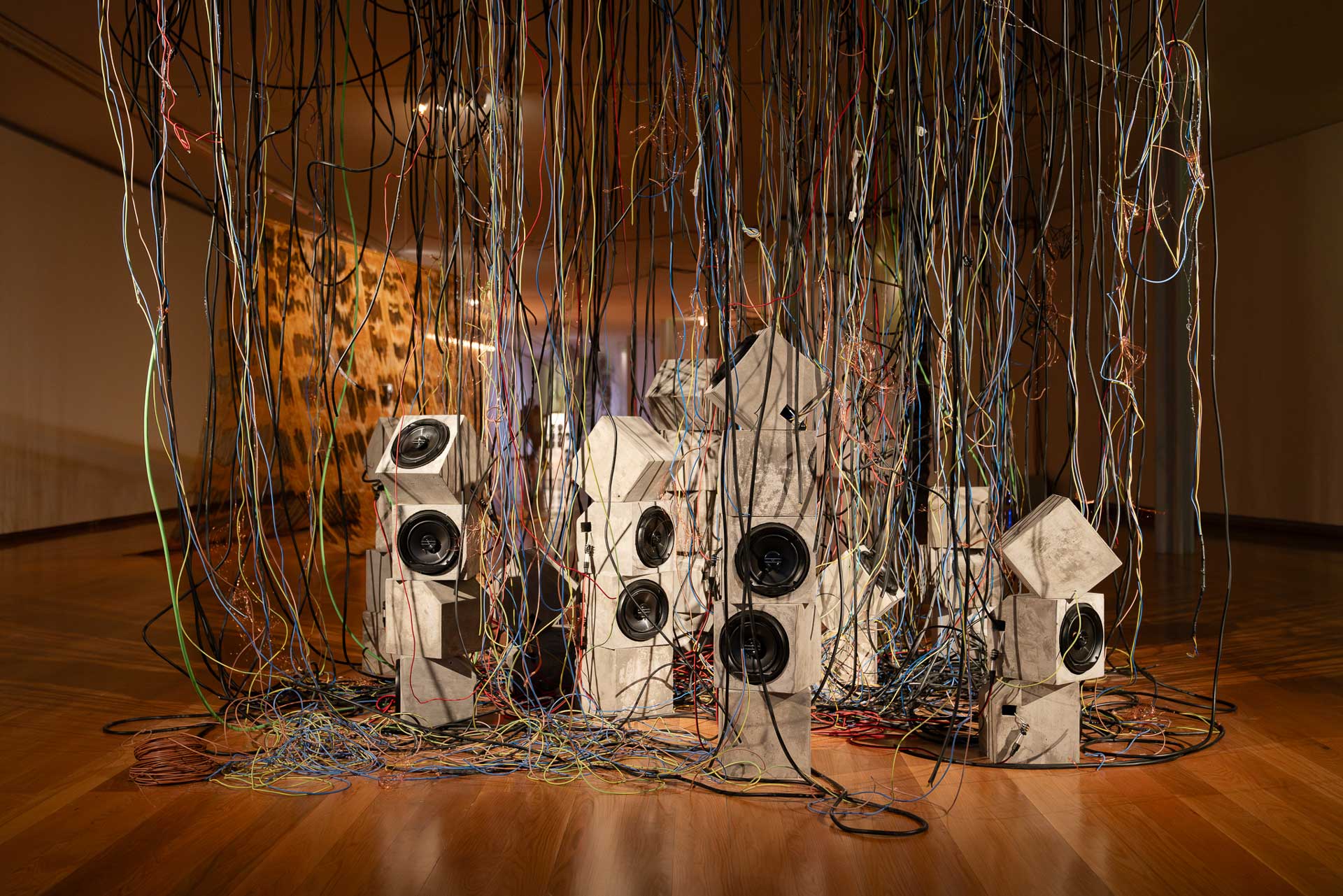

Left image: Exhibition View, Vivian Caccuri, Gatonet-Mor, 2024. Sound installation made of concrete speakers and audio cable, variable dimension. Courtesy of Galeria Municipal do Porto. Photo: Dinis Santos. Right image: Vivian Caccuri, Fourth World, 2023. Sound installation, speakers, amplifiers, stage lights, variable dimension. Courtesy of Noor Riyadh and Havas.

Courtesy of A Gentil Carioca Gallery.

VC: Exactly. I’ve destroyed or worn down several of them to achieve a certain aged or spatially traveled effect. So that’s usually how I choose the materials and techniques I use. Early in my practice I tried working with wood, but wood is among the super slow and difficult materials — it’s so tough that I’d lose interest halfway through.

LS: Wood is very dense, and your materials tend not to be. So if the work needs density, it comes through collaboration, because in your language, in your development, that doesn’t come from you. That’s quite beautiful.

VC: It’s also about a choice of path, you know? To work wood properly, you need a whole workshop and you have to fully commit. Maybe my experience would’ve been better if I’d had the right tools, but I didn’t.

LS: Did you do Vipassana [an Indian meditation technique focused on seeing things as they are] by any chance?

VC: I didn’t.

LS: Because your walk is kind of like a Vipassana, no? A kind of vow of silence.

VC: Yes. But, you know, I think the walk is more about getting your hands dirty than abstaining. When people ask me that, I always say both things can be part of the experience, but I think the silent walk is more about contamination.

LS: So that’s when the construction mesh appeared. And the mosquito netting — how did you find that? Or did the sound of the mosquito come first? Was it during the residency for the 32nd São Paulo Biennial that you did in Ghana where you came across it?

VC: The mosquito netting came first and brought the mosquito along with it. In Ghana, I started to understand the mosquito differently. In Brazil, I found these nets on the street and they were super dirty, smelled like cat pee. I washed them and everything, but they were quite limited in size, and eventually I wanted to scale up, so I started looking for other nets, where to buy them, what to do. That’s when I came across mosquito netting, which I could unravel the same way because it has a similar weave to construction mesh, but it’s more labor-intensive because it has more threads.

LS: It’s tighter, right? But maybe the construction mesh is a bit stiffer too.

VC: No, it’s the opposite. The construction mesh is super strong because it has twists on the vertical axis — something the mosquito netting doesn’t have. Anyway, I saw that the process was very similar, even if it came with other challenges. I still wasn’t painting on the mesh at that point, just working with it in white or black. And then I started adding color through another mesh and had a very limited palette, which actually helped me.

LS: Which other meshes had color?

VC: The construction ones already come in color.

LS: Oh, I see. So the mosquito netting gave that veil effect.

VC: Exactly. Or the black mosquito netting, which is called sombrite — same material, different application. At that time I was in Ghana, I’d had the idea of making an altar for the subwoofer for a while. Then I did a test with a candle and the speaker.

LS: Is that TabomBass [2016]?

VC: That’s the one. The candle would react to the beat and I thought that was a cool idea. But I didn’t really know what to do with it, so I shelved it. When the invitation to the São Paulo Biennial came, that idea was really well received. So I started developing what the sound would be, not knowing if it would be a collaboration with other musicians or a composition of my own.

LS: You only knew it was low frequency sound [bass sound] [laughs]!

Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri. Photo: Luiza Sigulem.

VC: Yes! [laughs]. When I went to Ghana, I was finally able to understand what that sound was. But at the same time, through many conversations with many people, I began to understand malaria, which is just part of life there. It’s more common than dengue is here, for example. So I became very concerned because my stepfather has had malaria eight times, and what he told me was not pretty. I also met a certain curator who was completely paranoid—not just about malaria, but about many other things—and malaria kind of became a psychoanalytic metaphor for everything else [laughs]. That fear of a certain nature, a certain environment, the illnesses of a certain place… There’s something there that’s a projection of other domains, other places, other spaces. There are deeper issues involved. Even science itself is contaminated by the values of the eras in which it was developed, right?

LS: But if you think about it, these vectors, like the mosquito, also show just how interconnected we are, because it creates a path of contagion. During the pandemic, for instance, we came to understand that when someone visits your home, they bring their home with them into yours—and vice versa. We don’t enter a space without carrying where we’ve come from. Not only do I bring my house with me, but also the places I’ve been. Things are not disconnected, and the mosquito makes that very obvious. We are not isolated. Even when you’re inside your home, you’re still in relation to the outside world. I see that in some of your other works too—for example, these triangle pieces in front of us. It’s interesting that you mentioned attacking the material… I’ve always felt a kind of aggression in those shards of glass, and at the same time, there’s an acceptance of what the material is. They’re naturally threatening.

VC: I think the mosquito has that quality too. It’s a species that’s very close to us. I probably spend more time with mosquitoes than with people on many days of my life. It’s impossible to keep them out here in Rio—they always find a way to get in and be near you, you know? That’s something specific to our tropical life. When I show mosquito-related work in a colder place, or in the Northern Hemisphere, I have to explain that context. The mosquito brings Brazil with it.

LS: Even though you started developing this work in an African country. But you also brought Brazil with you.

VC: Totally. There were two emblematic moments for me: observing the behavior of that deeply paranoid curator, and a comment from a friend of mine about Africa. He said: the continent receives a lot of foreign entrepreneurs, but it hasn’t been gentrified simply because of malaria. As if the mosquito were a bodyguard protecting the identity and way of life there. It’s such an ambiguous thing, because the mosquito is a guardian, but it also kills its own population. So to me, the mosquito feels more like a polytheistic religious entity—or even the Old Testament God: not good, not bad, just doing what it wants with you and your fate, which lies in the hands of a higher power.

LS: That’s very rich. And going back a bit—when you said you were developing Tabom Bass for the Biennial, you were working in the low frequencies. And the mosquito is the antithesis of that, right? You fall into the opposite spectrum: the high-pitched.

VC: Yeah. And it’s such a fragile thing.

LS: A different frequency, literally.

VC: It’s like a color palette. Working only with red is like only working with bass… I like to work with a full spectrum of sounds and the powers of sound. But I think both have power, and I like to understand the transformative power of a certain sound. Bass definitely has that—it modulates masses and large groups, people, societies. And in a way, the sound of the mosquito also has that power, but from another place, in a different way. I keep thinking: when I hear a mosquito buzzing while I’m asleep, is it trying to communicate something to me? Is it affecting how I sleep? That sound already triggers millions of sensations and responses in me. It’s such a small sound, but it makes you move as much as a low frequency does. It makes you think a thousand things and brace yourself in a certain way.

Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri and Galeria Millan. Photo: Julia Thompson.

LS: I think they invade us in similar ways. It’s the external becoming larger. There’s a kind of permeation. Even when we look at your exhibition design and your canvases—work that once leaned against the wall now increasingly breaks away from it. Can you talk a bit about that?

VC: My way of working always involves integrating sound and visual elements. For example, I have this installation-based canvas called Skin Shield—it’s the installation of a sonogram, which came from the question: how can I think of a sonogram that exists in space and still reflects the sound waves it was based on? So that the same sound that generated the drawn sonogram is also present in the space. Bringing in different instances of the same sound starts to create a very specific feeling, which was that cloud of mosquitoes I was after.

LS: So you’re already working with layers, and these are other layers beyond the visual form. Is that right?

VC: Exactly. For instance, thinking about how a mosquito perceives people’s skin [laughs]—how it smells the skin, the pheromones… Skin is the target. So I tried to treat the solo show in Portugal, at Galeria Municipal do Porto, from that perspective—thinking about how to create different skins and points of attraction within a space, while also talking about my practice and something about Brazil in a very abstract way, without a clear word or image of what the tropical experience is. I also wanted to talk a bit about structures. To build the sound installation, instead of doing a clean, pragmatic setup with cables running neatly through the space, I chose to use “GatoNet” (an unauthorized patchwork internet/electric/gas hookup), because that’s also a way of organizing—just not one that follows the standard idea of efficiency.

LS: And which, in a way, also evokes this idea of invasion, of appropriation…

VC: Yes, it’s something that stems from immediate needs that can’t wait for elaborate formatting, which has a lot to do with Brazil. We don’t have underground utility poles—our cables are all above ground. I had done something similar years ago at MAC Niterói [Água Parada, 2018]. It’s extremely difficult to do an exhibition there because that modernist monument is a protected site. There’s no space to run wiring, the carpet is protected, and you can’t really touch anything. So I solved the problem by creating a sort of “GatoNet,” and it worked great because it complicated that space that hides all of its infrastructure—plumbing, electrical systems—so well.

LS: Which has so much to do with modernism.

VC: With a part of modernism, right? Brutalism is the opposite—it exposes those systems. But anyway, that came about out of necessity for that specific exhibition. But when I bring that element to Portugal or Denmark, it becomes exoticized because “GatoNet” doesn’t exist in Europe. It twists how they understand what electricity even is. Why is there a cable coming out from here, connecting with another one that goes like this or that—and yet it works? Most of it is theatrical, you know? And I find that theater really compelling.

LS: Which also makes me think that your work is very political. It’s not a flag-waving kind of activism, but bringing in these cultural issues is, in itself, highly political. And in that sense, I’d like to talk about the triangle—Trítono Frágil, that glass multiple. How did the triangle enter your work?

VC: The triangle came about in an interesting way. It started from a different project, for which I composed a piece using mosquito sounds and a magnificent church organ in Scandinavia—so magnificent I actually cried when I had to say goodbye to it. It was a musical conversation that led to my only vinyl release [A Soul Transplant]. For that composition, I was looking for something that could evoke a kind of ritual, but not in a literal way, and that’s where the triangle came in. It’s used in orchestras, but it has roots in Egyptian ritual practices, so I asked for one from the person in charge of instruments. I had so many privileges in that residency—I should’ve been more aware of them.

LS: Was this a residency specifically for working with musical instruments?

VC: Yes, it was a residency at Luleå University of Technology to compose within a concert hall. I could’ve formed a choir or worked with a cello if I wanted. Since working with a church organ is such a rare opportunity, I chose that, but I could still request other materials, so I asked for a triangle. And the person in charge of the instruments burst out laughing and said: “Vivian, you’re working with this gigantic instrument and now you want a triangle?” I explained that I wanted to create a section in the composition that felt like the organ sound was melting—and the triangle would come in at that point. Then I started playing forró on the triangle. And they loved it because they had never heard a rhythm like forró before. The orchestral triangle has certain time signatures, but it’s almost seen as a toy, a lesser instrument. And I became very interested in that aspect, too.

Vivian Caccuri, Água Parada, 2018. Concrete, speakers, piano, cables, stereo audio, variable dimensions. Courtesy of Solar dos Abacaxis. Photo: Renato Mangolin.

LS: But I also see a connection between the organ—which is massive and metallic—and the materiality of the metal triangle in your hand, which feels a bit like “GatoNet.” And again, back to air, to transparency, to fluidity in your work. But this is a more hands-on interaction, right?

VC: Yes. When you sit down to activate the diaphragm, the organ makes this beautiful sound like a sigh. The one I used was extremely classical, but it had a digital component, so there was a whole process to get it going. When I started playing, I would get startled because it felt so monumental, so far removed from my body. It was more like activating a building, not just my own body—many bodies, including the architecture’s. And the triangle is the opposite.

LS: Sort of marginal. But if you think about it, the triangle and the bell both fall into the realm of the sacred. There’s something about metal, about it continuing to reverberate in the space, altering the frequency, resonating through the body.

VC: Correct. In ancient Egypt, the triangle was considered a ritual object that centralized time and collective presence. Today, it’s the joke of the orchestra [laughs]. It’s what you give to the kids. It’s diminished, stripped of its sacred significance—which I found very compelling.

LS: And at the same time, the organ is God.

VC: It’s a spaceship. So I went through the exercise of rethinking the triangle—what if it hadn’t lost its status? What would music be like then? How can I give majesty back to this triangle?

LS: How does something become nothing—and nothing become something?

VC: Exactly. I made a multiple that followed that line of thinking, but using the instrument’s current shape, which has already been stripped of its former power. In ancient Egypt, it didn’t have this geometric triangle shape we know now. It was a different kind of object, but with a similar sound. It was really exciting to work with the triangle. I did a large installation at the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo [Ode to the Triangle], which was a pendant of triangles that could be played all at once. I invited various musicians to activate the space—two of them composed a piece for triangle, and a musician from Cariri created a very avant-garde forró interpretation of the instrument. The pendant included triangles from all over the world, with different textures and finishes. There’s a musical genre from the southern U.S.—Cajun music—which has roots in French colonies and uses the triangle both like a fiddle and a percussion instrument. It’s very similar to forró. So it’s fascinating that the triangle has a strong regional identity in so many places and has morphed differently in each context.

LS: There’s something tropical and diasporic in that too. And it’s interesting how very different places come up with such analogous solutions because they face similar conditions that lead them to the same objects. I find that liberating because it kind of deflates the myth of the genius, right? Sometimes it’s just a response to a shared set of problems that results in a similar solution. And not everything came from Europe [laughs].

Exhibition view: Vivian Caccuri, Ode to the Triangle, 2019. Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri.

VC: Yes [laughs]. And visiting the African continent and learning more about several local music genres… The music industry in Nigeria is unbelievable. Ghana’s is smaller, but still strong. It helped me realize how we Brazilians can be a bit precious. For instance, I was talking about the berimbau with someone over there, and they told me they hated it. They said, “Wow, you’ve had the berimbau for, what, centuries? And never thought to add another string, tune it differently, or try something new? Meanwhile, here we make new instruments every day, with cans, gourds, fishing lines, animal skins, and electronic objects.” And it’s true. We’re so afraid of losing our roots that we freeze objects in an immutable, sacred, consecrated state. We’re scared they’ll disappear. It’s a very different mindset.

LS: I also think it’s a culture of doing a lot with very little. And it’s almost a miracle to innovate with an instrument that offers so little, right?

VC: But it’s not just the instrument. There’s an entire culture around the berimbau. The presence of that object defines a culture, and in Brazil, it becomes part of our national identity. What I found interesting in the instruments I saw in Ghana is that even the new ones—those invented on the spot or rethought by musicians—can also carry that national weight. It doesn’t have to be sacred to have that kind of power.

LS: It’s something more dynamic. Maybe the root of it is our Portuguese side, which tends to be more conservative.

VC: Canonical, even. But there’s also the omnipresence of the Portuguese language. In Ghana, they speak over ten different languages, which makes things much more dynamic because each people, each ethnic group, has its own roots, and that creates a constant cultural clash.

LS: And people speak more than one language. We started by talking about my Peruvian father and Brazilian mother—so there too, there must be families where grandparents and parents speak different dialects. That’s always enriching because it allows you to see the same thing from many different perspectives, through language. When I think about the verb estar, which doesn’t exist in English but does in the subjunctive of Latin languages… All of that enables a very specific kind of thinking tied to that structure. If you don’t have the structure, how do you even develop that kind of thought? It’s really difficult.

VC: Totally.

LS: Vivian, I’ve been following your work for many years and you always have so many things happening in so many different places at once. What’s going on in the world of Vivian Caccuri right now?

VC: I just wrapped up an exhibition Siluetas Sobre Maleza at Jumex, in Mexico, and another called Febre da Selva Elétrica in Porto, Portugal. There’s a sound piece in Russia at the VAC Foundation. Mosquito Shrine, which is one of those large embroideries, is on view in London at the Wellcome Collection. And I also have an upcoming show at MOCA Tucson, in Arizona, USA, with a sound installation, a residency and solo show at the Mattress Factory in Pennsylvania, plus two charcoal drawings at Victoria Miro in Venice.

LS: That’s a lot—wow! And do you have any solo shows opening at a gallery this year?

VC: Yes! In September, at A Gentil Carioca.

LS: A packed year [laughs]! Thank you, Vivian. It was a pleasure talking to you.

VC: Thank you, Lu! Always lovely to chat with you.

Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri.

To learn more about Vivian Caccuri’s work: @viviancaccuri // www.viviancaccuri.com

To know more about Lu Solano: @lusolano_

To learn more about Art In Brackets: @artinbrackets

Vivian Caccuri, Mosquito Shrine IV, 2022. Protection screen, iron bar, waxed thread, cotton thread, bitumen, acrylic paint, aluminum, 92 1/2 x 171 1/4 x 1 1/8 inches. Courtesy of Estúdio Vivian Caccuri.