Bernardo Mosqueira: First of all, Regina, my dear friend, thank you for this conversation. We’ve known and collaborated with each other for many years. I began curating exhibitions in 2010, and by 2011 we were already exchanging ideas—exchanges that have always felt extraordinary and deeply meaningful to me. Over the years, we’ve worked together on at least ten exhibitions and programs, and I genuinely feel that I’ve grown as a person, curator, and collaborator through our dialogue. In these nearly fifteen years, a lot has changed in the world and in our personal and professional journeys—and this is the first time we’re publishing a conversation between us.

Regina Parra: My dear Bernardo, I also hold so much affection for our encounters, which—as you said—are always incredibly special. I think you challenge me in exactly the right ways, and you have a remarkable generosity in how you engage with the work, allowing it to speak for itself. I’ve learned so much from you.

BM: Thank you. I’ve learned a lot from you too. It’s a real privilege to feel that you’re growing alongside someone over time. So let’s dive in. Our conversations tend to follow spiraling paths, but today I’d like to propose that we start at the beginning—or at a beginning, since every beginning is a bit arbitrary. Would you say your first real works were the ones from your debut in FAAP’s annual exhibition in 2006?

RP: That’s right. I think I first participated in the annual show in 2005, and I believe I was awarded in 2006.

BM: Yes! You won the top prize that year.

RP: I consider those my first real works, even though I started painting when I was about eleven. I always painted, but I joined FAAP [to study Visual Arts] in 2004 after studying Performing Arts, so I was a bit older than most students. At FAAP, I was exposed to more contemporary art and quickly realized that the painting I had been doing wasn’t very good [laughs]. The great thing is, I came to that realization on my own, which spared me from any trauma. I simply saw that what I was making didn’t make much sense, so I stopped painting and began exploring video, which felt more in tune with contemporary practices.

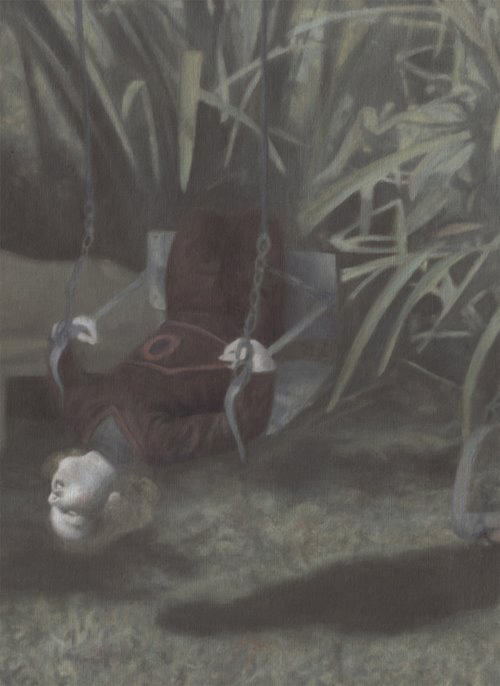

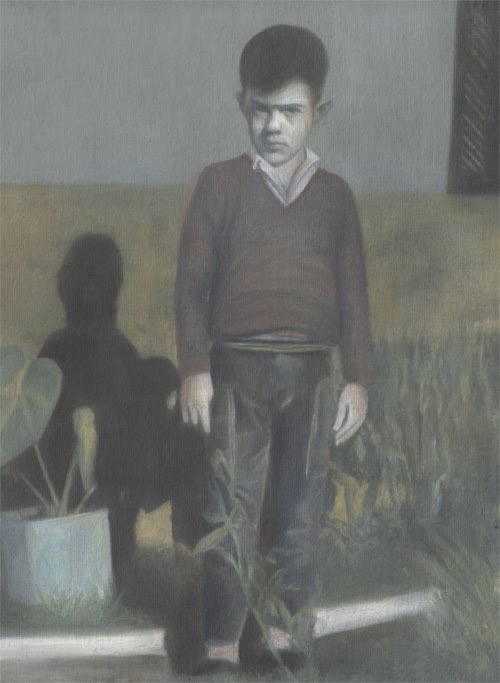

But painting was always something I loved. In 2005, I started painting again—not with the intention of making “art,” but because I truly felt the need to. There was no pressure, no expectation. That’s how those pieces ended up in the exhibition. They were small works on paper—I didn’t even want to spend money on canvas. It was just a personal exercise, based on old family photos. There was something about those images that unsettled me. I remember telling you recently about one of them—my father holding a balloon right before it floated away, but the way he looked downward… it felt almost dreamlike. Another photo was of my sister and me with someone in an animal costume. The costume was so crude, and I could never tell if it was meant to be a rabbit or a bear. It was this strange, misshapen creature standing next to two tiny kids. And the third image was of a girl on a swing. All of the works had a very limited color palette, as I was still learning about color. I see those paintings as my first because they were the first I ever exhibited—at the FAAP student annual. And it was meaningful to discover that they resonated with other people. I felt really proud of that.

Regina Parra, Álbum de Família, 2005. Oil on paper, 11.8 x 7.8 inches each. Courtesy of the artist.

BM: I find it really interesting that this body of work was your first for two reasons. First, because you begin, in a way, by confronting one of the most powerful institutions that upholds hegemonic power structures and patriarchal norms: the family. By looking at it through your painting, you assert your own perspective on the familial experience, positioning yourself as the author, as an autonomous voice. There’s a kind of rupture in the institutional repetition of family narratives, and your substantive, individual vision emerges—even at that early stage of your practice. There’s also a kind of seed being planted, a connection between oppression and insubordination, when you reclaim authorship over your family’s memory. These concerns would go on to become a constant truth in your work, manifesting in different ways over the years. How do you see the development of your interest in themes of oppression and insubordination over time?

RP: I think that development happened in a way that wasn’t so conscious, but it was always there. If I think in linear terms, in the beginning, it was more focused inward—on the idea of family. Later, when I began working with surveillance camera imagery, I became interested in how bodies are disciplined, and in the subtle but very real discipline inherent in the systems of surveillance we live under. After that, I moved into research related to immigration, which is also about who can and cannot move freely through space. What are those borders? Who gets to define these visible and invisible boundaries?

Then I started looking more deeply at the body itself—even though the body was always present in my work. I’m really interested in how the body is almost always in a kind of internal battle, struggling to free itself, to be free—something I think we still aren’t. Speaking for myself, I’m constantly questioning how free we really are and how much we’re still holding onto both internal and social constraints. So, my work moved more directly toward the female body—a body that lives under oppression and must be insubordinate. I’ve been thinking a lot about those marks, those movements of the body opening and closing.

BM: We’ll come back to some of those points later, but there’s something I want to touch on now. In previous conversations about those early paintings, I remember you saying you didn’t want to keep focusing on your family because you didn’t want to become overly self-absorbed. I’ve also had the privilege of sitting in on your classes and have heard you share this idea with other artists—that art, in your view, has a public function and must engage collective concerns. How do you think about the public function of your work today? What are your responsibilities as an artist?

RP: I’ve always been careful not to make work just for myself. That’s actually why I consider that first body of work to be my true beginning—because it went out into the world and connected with other people. That connection has always felt essential, even in my own process. I’ve never been someone who can just create in a vacuum. I’m deeply affected by what’s happening around me, by what we’re all going through. And usually, those things aren’t very positive, which naturally impacts the work.

I believe art has the power to transform. And that transformation is powerful precisely because it’s subtle—it creates space for imagination, for envisioning new realities. For a while, I was mirroring some of the difficult dynamics I observed in the world. But more recently, I’ve been trying to shift toward creating alternative possibilities, imagining new universes, rather than simply reflecting the existing ones. That’s what I tried to do in the recent exhibition I’m part of with Lisette [Lagnado], titled Lilith – Imagining a Pagan Paradise. Instead of just complaining about the Catholic paradise—which is boring, patriarchal, and misogynistic—we imagine a different kind of paradise, creating it through images or immersive experiences.

Art has the capacity to generate new possibilities. If you look at my neon works, for instance, they’re about creating a space for poetry and exchange—something that often doesn’t exist in the daily life of a city. I think this openness to sensitivity and poetry is, in itself, deeply political—especially in a world as brutalized as the one we live in today. I’m not sure if I answered your question… I think I got a little lost [laughs]!

Regina Parra, Lilith – Imagining a Pagan Paradise, 2025. Installation with oil paintings on paper on aluminum with clay structures, and acrylic on cotton fabric. Exhibition view from Nossa Senhora do Desejo, curated by Lisette Lagnado. Almeida Dale Gallery, São Paulo. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

BM: All good. In the best cases, we answer and also get a little lost [laughs]. Thinking about that pagan paradise, I want to bring up another Christian reference that also appears in some of your early works. I’m thinking of that series of small paintings on paper, still part of those first pieces, made from images of your parents’ visits to the Basilica of Aparecida do Norte—your parents being devoted to Our Lady of Aparecida. That series is really fascinating, and the story of Aparecida itself is incredibly rich. A group of fishermen from Guaratinguetá decided to host a celebration for the governor of the Captaincy of São Paulo and Minas de Ouro, who was visiting the region—this man would later become the Viceroy of India, so the story is tightly linked to colonialism. The fishermen couldn’t catch anything because it wasn’t fishing season, but then they ended up pulling from the river the body of a headless saint, and later, the head—so, a dismembered woman. When they joined the head to the body, it became so heavy they couldn’t move it, so they began to pray. Then, when they fished again, they suddenly caught many fish. This was considered the first miracle of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Aparecida. She went on to become a figure of collective worship there, especially among Black people, and eventually the patron saint of Brazil.

It’s a story that merges colonialism, a dismembered woman, a relationship with nature, and themes of gender, class, race, and faith—all deeply embedded in power structures and social hierarchies. And it’s interesting how all of these themes are present throughout your work, along with ideas about the power of ritual and faith as an act of courage—a belief in possibility. “The body that insists,” right? How do you see that central concept of “the body that insists” and its relationship to desire and power structures in your work?

RP: What you said about faith as the courage to believe is so beautiful. It reminds me of a quote I love, from a book recommended by Contardo Calligaris: “Desire is what we do to survive.” I think that relates to what you’re talking about—the body that insists—because desire is what holds us together. It’s what drives us. Any kind of desire. And as our desires shift, the body continues to insist. That urge toward insubordination, which you mentioned earlier, is also born from desire.

As for the Aparecida series, it came from photographs of family members of my parents who used to visit Aparecida to fulfill promises. They would always take a photo as proof that the promise had been kept. I was always captivated by that. I found myself imagining: what was the promise? What was the desire behind it? The photo served as a record of a fulfilled wish, as if the image could somehow contain that desire. I still look for images that might, in some way, translate desire.

When you mention power structures, I think there’s always some form of desire to defy them—to resist imposed limits. Depending on where I am in life, that desire shows up in different images or series. That Aparecida series was from 2007. Then, in my 2019 exhibition Bacante at Galeria Millan, the paintings were all inspired by the myth of the Bacchantes—those wildly liberated women who performed ritualistic orgies in honor of Dionysus. So again, you have faith—but here, faith is linked to sexuality, to bodily liberation. I felt it was especially important to create that show in that political moment, just as Bolsonaro took office and ushered in a wave of conservatism in Brazil, which would further restrict women’s freedoms. I loved the idea of imagining the Bacchantes—completely free women using their own bodies, even as a way of worshiping a god. The liberation of the body is also tied to a kind of spirituality, and the body becomes almost a utopian space—one through which we can reflect on a time of oppression.

BM: That’s a really compelling idea you’re describing—the very act of exercising freedom as a form of worshiping life and its possibilities. There’s something deeply celebratory in your work—of life, of what’s possible, of connection and freedom—with the body always at the center, always in motion. I remember the first time we met, back in 2011, you were developing a project for Videobrasil during your residency at Casa Tomada, right?

RP: That’s right.

Regina Parra, The dangerous one, 2019. Oil on paper, 47.2 x 35.4 inches each. Bacante exhibition view at Millan Gallery, São Paulo. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

BM: And it was precisely that piece [As Pérolas, como te escrevi] in which you were already paying close attention to immigration issues. It’s very striking to look back at that moment in 2011, when neither of us knew we would become immigrants ourselves. Now we’re having this conversation here in New York, where we’ve both lived for some years, and I wonder how you see that work today, given the distance in time and change in perspective. In that piece, you worked with a group of immigrants with diverse backgrounds and experiences, in the context of São Paulo at the time, and you invited them to read excerpts from Mundus Novus, by Amerigo Vespucci. I’m curious how your own experience as an immigrant may have changed the way you view that work.

RP: I think about that too. Our perspective changes. There’s a writer I really like and followed more closely back then—Julia Kristeva—who wrote a beautiful book called Strangers to Ourselves. In it, she tries to understand the roots of intolerance and argues that, when you encounter a foreigner, it provokes you because here is a person who gave up so much—family, country, whatever it may be, everyone has a different story—but gave all of that up in pursuit of a desire. This is someone who has crossed over. And when we meet a foreigner, in a way, we’re forced to ask ourselves: what have we crossed? She links that confrontation with the root of intolerance. We’re talking about the force of desire that drives these bodies, even if it’s a desire to escape terrible things. I heard some truly horrific stories while working with the Migrant Support Center [CAM], which assists refugees. Brazil is actually quite open in that regard—it’s not like here [in the U.S.]. There, you’re not treated like a criminal when you arrive; you’re offered support. I had a deep desire to go beyond the surface of those stories and engage with those people. At first, the project didn’t work at all. I had the text by Amerigo Vespucci—which describes Brazil as a paradise overflowing with pearls—and I invited some refugees to read that text on video, which turned out to be quite a violent gesture. I ended up discarding that material and realized, of course, that this was a piece that needed collaboration and intentionality from their side. It wasn’t about hiring foreigners to read a text—it had to involve real engagement, to get their own reflections and experiences with the text. So in the second phase, which is the version you’re referring to, I spent about two months talking with this group. Of course, our situation is entirely different from theirs—we’re not refugees—but Kristeva’s text resonates deeply with me. No matter the circumstances, the foreigner is always someone from the outside and will never fully belong, which is a very delicate thing. I also think a lot about [Jacques] Derrida, who said that tolerance isn’t enough. Tolerance means putting up with something—it’s different from truly opening yourself to it. He spoke of absolute hospitality, of letting someone into your home and allowing them to move the furniture around. To be confronted by the other and to allow space for that. And that’s what’s most difficult and most fascinating—and it’s also what we’re living here.

BM: The immigrant or foreigner experience is incredibly powerful, because regardless of the reason or means, it transforms dissatisfaction into mobility. So there is this profound connection between desire and movement. The foreigner, as someone who carries and transforms culture, brings something essential and powerful to the collective—an entire alternate system of “ordered world,” and also the strength of insubordination. Someone who crossed the world to pursue a desire or the will to survive, as you said. And yes, both Derrida and Kristeva express that beautifully. One of the things Kristeva analyzes in that book is how immigrants or foreigners are represented in Greek tragedies. Greek myths and theatricality were with you even before the visual arts. What’s the importance of theater and your work with [director] Antunes Filho in your journey?

RP: I studied Performing Arts at ECA [University of São Paulo], but ended up leaving the program when I started working with Antunes, because the process was so intense—day and night, no holidays, no breaks. First, I got into a theater course through a selection process—it was called CPTzinho, a part of his group. Later, I joined CPT, which was his main group, and then started working as his assistant director. You don’t realize how deeply that experience shapes you until time passes, but now I see it’s still a big part of me and how I work. After Antunes passed away, I revisited a lot. Right after I left theater and shifted to visual arts, I kept those two worlds a bit separate. But I joined Antunes so young—I had very little cultural experience. All of my foundational training happened there, with him. Even though we lived and breathed theater 24/7, he always said theater was just a vehicle—the real aim was to explore human questions. His creative process was extremely broad. I started working as assistant director on Medea, which we rehearsed for a year and a half, maybe two—and that’s when I completely fell in love with Greek tragedy. But we also read rhetoric, philosophy, watched films about Eastern philosophy, studied German Expressionism, Taoism, Buddhism, pre-Socratic thought—he wove all of that into the creative process. There were even references to fashion—he loved Alexander McQueen. And I think I’ve tried to carry that into my own process: starting very open and slowly narrowing in, experimenting, discovering what works and what doesn’t. Even if the final result is just a tiny painting, it still carries something of that whole universe I wandered through—at least I hope so. And I can’t do anything without having a text to structure it. I need a skeleton for things to flow, and I think that habit comes from theater.

And theater still shows up in other ways—in Bacante, which we talked about earlier, in the occasional neon that uses text from [Samuel] Beckett, and more broadly in how I structure space in exhibitions, for example.

Regina Parra, As Pérolas, como te escrevi, 2011. Project developed for Videobrasil during a residency at Casa Tomada. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

BM: I wanted to return to the question of the body in movement. You spent several years of your life, in your body’s personal history, dealing with significant issues related to movement.

RP: Yes. At a certain point I had a health problem that affected my mobility a bit, so I lost muscle mass and didn’t have the strength to move or do very basic things. I think it started in 2013 and lasted until 2018, and towards the end, I even needed a wheelchair and various supports to hold up my own body. So, if we think about the video 7,536 Passos, from 2012, in which I walked a route on foot, I went from a place of mobility to a terrible immobility. But then something interesting happened. When I couldn’t even sit up, I ended up spending a lot of time lying down — I even had a mattress in my studio — but my mind kept going, and once again, I return to the idea of desire. I became very interested in dance and watched a lot of videos. I’m a very obsessive person, and it was like that with contemporary dance — and in a way, I think it made me feel good to watch people dancing when I couldn’t dance. It was during that time that I began collaborating with dance people, like Bruno Levorin, who is a choreographer, and the dancers Clarissa Sacchelli and Maitê Lacerda. That project helped me a lot, even in the healing process, because through it I began to investigate the body, movement. Where does this movement come from? But since my body wasn’t functioning, I had to think about other possibilities of movement, and with that you start to understand other blockages in your body that aren’t muscular. I think I’m still in that research. I’m better now, obviously, but the body is still a place of great interest to me. Especially because when I got better, I had the joy and the chance to relearn how to climb stairs, ride a bike, and then you get the chance to reposition your body.

BM: Incredible. And did you return to painting as well?

RP: I never stopped painting, even when I was unwell. I’m very grateful to painting because without it, and without this collaboration with the dance folks, I wouldn’t have made it through what I did. I didn’t have strength in most of my muscles, but my fingers still worked, so I painted using my wrist.

BM: And when did you begin developing this series that intertwines still life scenes with some form of portraiture, in which the body doesn’t always appear or appears fragmented?

RP: I find the name of that genre so funny… and I never thought I would end up doing that. I made the first one in 2019, for the Bacchantes exhibition. There were three large paintings with that image, and below them I wrote on the wall a bit about a kind of ritual that this Bacchante would undergo, like an offering of herself. But I think those images are less about fruit and more about the body. I see them as body, even knowing they’re fruit. So for me, still life is very much about life. And I actually like that there’s a piece of body together with the fruit, because I treat them the same way. These paintings need to be big, larger than life-size, because then you look at the fruit as a mass, a musculature, a weave, that sometimes feels like a body to me. I think that original idea from 2019 still persists as an offering, and I think a lot about these paintings as a place of celebration of life, of life force, of touch, a place of the erotic, where things meet. We became very disconnected from the erotic since the pandemic, especially here in the United States. It’s awful. People became even more closed off to physical contact. So these paintings, for me, are somewhat about contact, about warmth. We need the erotic. And I also think this was a response, of course, to the experience of having come very close to death. I was incredibly lucky not to have passed. I’m still in this moment of celebrating life, and I remain somewhat fascinated by everything we can live and experience.

BM: I love these paintings for many reasons. On a personal level, I love them because I recognize in your reference to this painting category — still life — an affirmation of the value of life. To me, they say that life can end at any moment, but at the same time, they say that yours didn’t! So personally, as your friend, they are deeply emotional paintings for me. And I celebrate these works and your life immensely! But beyond that, in a reading that’s a bit less Cancerian, I love the absolutely erotic formal approach. Not erotic only in the sexual sense, but also in the sense of the porous body’s experience of overflowing, of losing itself in presence. That state where, temporarily, you find continuity with the whole, just before returning to your own edges. Maybe a relationship between near-death and the little death. These wet bodies and fruits seem like things that are overflowing their own surfaces, their own contours. And there is a very powerful erotic force also in this idea of offering and sacrifice. To witness an offering, or to make one — to give something alive over to its unmaking — is above all a celebration of being alive, of having boundaries. You offer something that is alive to the continuity of the planet, to affirm, to celebrate, and to nourish the very fact of being alive. And I also see this strong affirmation of life very clearly in your neon works. A series in which I still recognize your sense of public function that is established through the works’ relationship with the city, placed in transit spaces, bringing poetry, subtlety, complexity, ambivalence, inspiration to everyday life — mixing the experience of art with the rest of lived experience. I’d like to mention two of those works that seem strongly related to me: A Grande Chance and Aterradora Liberdade.

Regina Parra, A Grande Chance, 2015. Neon installation, 118 x 78.7 inches. Installed at Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, on the occasion of the exhibition Encruzilhada. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

RP: Yeah, neon has a more direct and clear public function than painting, perhaps. Of course, painting can surprise us in that sense, but neon has a broader reach because when it’s installed in a public place—be it a park, a square, or Largo da Batata [São Paulo, Brazil]—everyone sees it. It really is a public work. Which causes me a bit of concern because, although it seems easy due to its public nature, it demands relevance and the establishment of a point of connection. Neon is very seductive—it’s a glowing red-orange light that makes people want to come closer. But at the same time, it’s not a material traditionally associated with the art world, so if you don’t read the phrase, it just becomes another element in the city. It’s visually appealing on its own, but it’s not a virtuous thing. It’s used in flower shops and sex shops, and it even went through a period of decline. And the neon always comes with phrases that haunt me, as something subjective that I share in public space. A restlessness, a question. So, for example, The Big Chance was installed in Parque Lage [Rio de Janeiro, Brazil] during that exhibition you curate [Encruzilhada], but in a more remote spot, in the middle of the park, allowing for a kind of discovery. That phrase came about during a time when I was undergoing a series of treatments for the illness I had—which, in truth, has no cure. Of the four treatments that exist, I had already done three, and none worked. Then came the attempt of a last treatment that was really alternative, very strange, and disgusting. Experimental. My big chance. And I had to sign a bunch of documents confirming I understood that it could go wrong.

I’ve always been bothered by events dressed up as “the big chance,” “the great opportunity,” because I find the buildup of expectations around that meeting, that encounter, that moment very scary—even though it can, in fact, be a space of possibility. That’s where this neon came from. It’s beautiful and came from a feeling of fear and apprehension, but people have always had a positive reaction to it. I’ve heard so many stories—people leaving toxic relationships, people getting married…

BM: And Terrifying Freedom?

RP: That’s a new neon I’ll be showing now in May [2025]. It came from a passage in The Passion According to G.H., by Clarice Lispector. It’s a question we pose in the face of freedom, also in the face of a big chance. It’s about the panic that arises when we’re confronted with freedom. A freedom that also comes from a search and that desire for insubordination we talked about—and the fear that comes from total freedom.

BM: That’s so beautiful. The Big Chance also seems like a call to presence to me. To be present in a certain place, almost like an invitation to encounter one’s own ontological state of crossroads—understanding that the crossroads is not some extraordinary state, but simply what it is to be alive. Living is being at a crossroads. Possibilities can be the big chances—whether we’re aware of them or not. And that can be either exciting or terrifying. And the same goes for a terrifying freedom, which is also a call to presence.

RP: Yes, grounded.

BM: Terrified, but also grounded.

RP: Both. It’s about feeling both feet on the ground—the loss of the third leg, as in Clarice’s book, which is terrifying. But also having both feet on the ground, aware of the autonomy to take the next steps. And in that sense, it’s very much connected to the idea of a big chance to encounter your own freedom. Within yourself and on your own two legs.

BM: Maybe I’ll use this moment, in which we’re evoking both freedom and walking, to celebrate all these years we’ve walked together and nourished each other’s freedom. Since we have to end the interview, I do so with the wish that we keep walking together, exchanging, and nurturing our friendship and our freedoms for many, many years. Thank you for this wonderful conversation today, my friend.

RP: Thank you, Be. It’s always so good to talk with you. I even took some notes here. Thank you so much.

Regina Parra, Venusberg, 2024. Oil on paper on aluminum , 34.8 x 25.2 inches. Photo: Argenis Apolinario. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

Regina Parra’s work has been exhibited at institutions such as The Jewish Museum in New York (USA), MACBA—Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (Spain), Mana Contemporary in Chicago (USA), Americas Society in New York (USA), Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (Italy), Centre d’Art Contemporain d’Ivry (France), and the National Museum of Lisbon (Portugal).

In 2023, Parra held a solo exhibition at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo (Brazil). Last year, she also presented solo shows at Lyles & King Gallery in New York and Galerie Mighela Shama in Geneva.

Parra has received several awards, including the 3M Award for Public Art (2018), the SP-Arte Prize (2017), the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation Video Award (2011), and the Videobrasil Award (2011).

In 2024, she was selected for the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts program in New York; in 2021, for the Monira Foundation Residency Program; and the year before that, for the residency program at The Watermill Center. She has also been an artist-in-residence at Annex_B and Residency Unlimited, both in New York, as well as at Pivô, in São Paulo.

Her work is part of the collections of institutions such as MACBA (Barcelona), MASP, Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Instituto Figueiredo Ferraz, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco, Videobrasil, among others.

To learn more about Regina Parra @reginaparra // www.reginaparra.com

Regina Parra, still video 7, 536 passos, 2012. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.

Bernardo Mosqueira received in 2017, the Lorenzo Bonaldi per l’Arte Prize, an international award for young curators organized by GAMeC in Bergamo, Italy. His recent exhibitions include Luis Fernando Benedit: Invisible Labyrinths (co-curated with Laura Hakel and Olivia Casa, ISLAA, 2024); Korakrit Arunanondchai: but words create worlds (Solar dos Abacaxis, 2024); The Precious Life of a Liquid Heart (ISLAA, 2023); Wynnie Mynerva: The Original Riot (New Museum, 2023); and Pepón Osorio: My Beating Heart / Mi corazón latiente (co-curated with Margot Norton, New Museum, 2023). In 2021, he was part of the curatorial team for the fifth New Museum Triennial, Soft Water/Hard Stone. Mosqueira holds a master’s degree in curatorial studies (CCS Bard, 2021). In 2017, he was listed as “One of the 20 Most Influential Curators in Latin America” by Artsy.

To know more about Bernardo Mosqueira @bernardomosqueira

Hero Image: Regina Parra, Salome’s Navel, 2024. Oil on arches paper on aluminum, 60 x 45 inches. Courtesy of Almeida & Dale Gallery.