Some things come to us so naturally that, even when they require rational thought, the processes behind them remain almost unconscious. For me, working with wood is one of those things.

I can’t recall when I first became drawn to it. It feels as though wood and I have always been connected—sometimes closely, sometimes more distantly, like true friendships. This bond has been with me since my childhood, spent in the western region of São Paulo state.

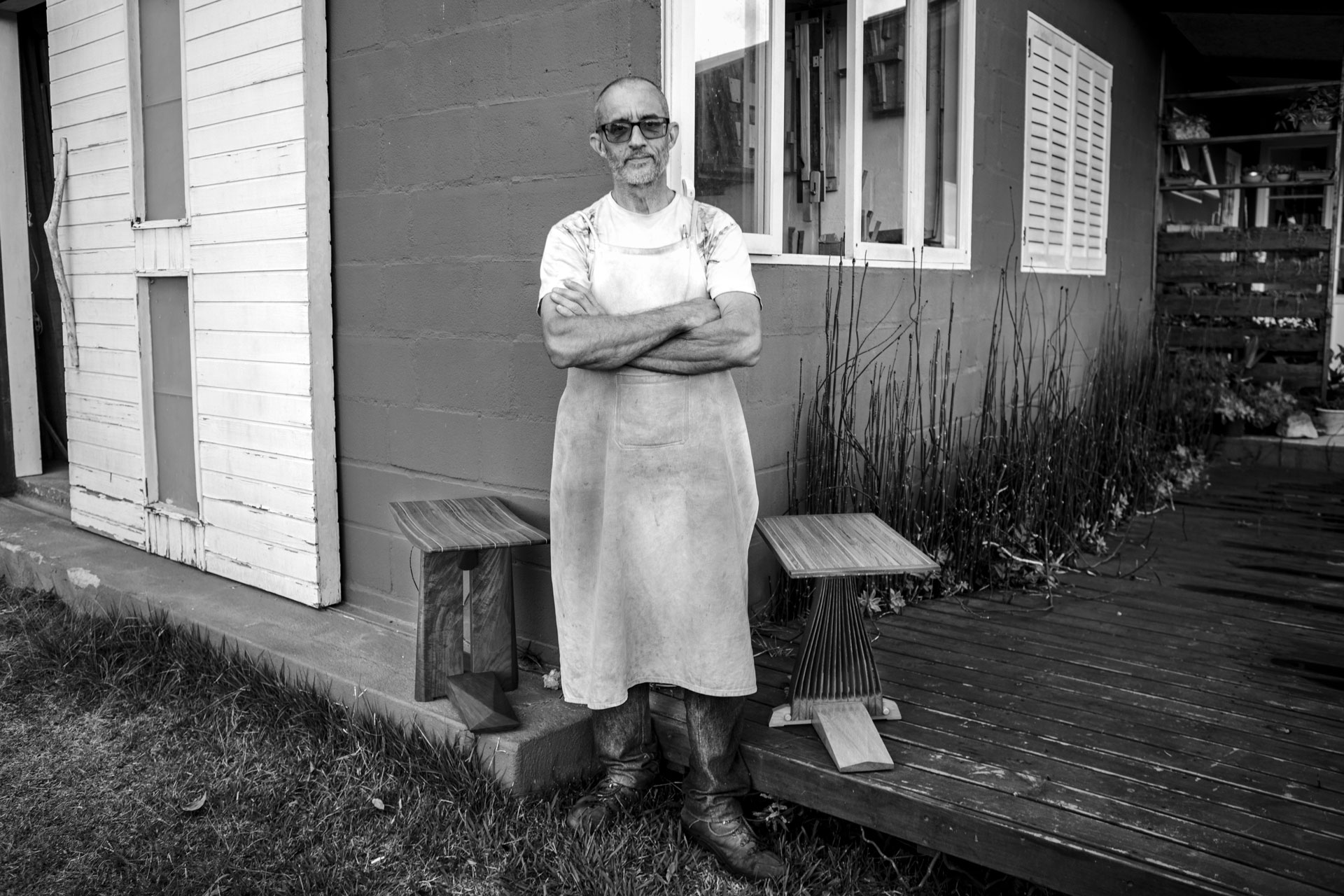

When it comes to woodworking, I have always been self-taught—curious, methodical, self-challenging, and, in many ways, still ignorant. Trees are some of humanity’s greatest allies: alive, they sequester carbon, provide oxygen, regulate humidity and temperature, offer scenic beauty, bear fruit, and so much more. Once dead, they continue to serve us, giving us at the very least charcoal, paper, and wood—materials we have ingeniously used since the dawn of humanity to craft objects and tools that accompany us from the cradle to the grave. It is within this second stage that the craft of woodworking takes root.

For every piece I create, numerous offcuts accumulate. Those too small or severely flawed are discarded; the rest are carefully stored.

In 1996, when I decided to leave São Paulo’s capital for a small town nestled in the Mantiqueira mountains of Minas Gerais, I brought all that wood with me.

After more than twenty years of crafting doors, windows, and furniture, countless scraps had joined the ones I had brought from the city. Whenever someone asked why I kept so many pieces of wood, I would simply say they were my retirement plan.

Even before the pandemic, a friend—aware of my growing stockpile and my intentions—jokingly asked how many more years I thought I would live. I got the message. I decided to stop buying new wood. From that point on, the approach was reversed: each new work would have to adapt to the available materials, their combinations, and their structural limitations.

The privilege of living atop the mountains, gazing out over an endless sea of peaks, reveals the intricate harmony of the whole and the crucial importance of every small detail—much like a symphony. Holding this awareness, both rationally and spiritually, I begin each new piece.

Each piece presents a different challenge. Just like each scrap of wood, every creation is unique and unrepeatable—even those produced in small series, which vary in their details. Naturally, this considerably increases the time required for each work. It would be much faster to start with a full plank and simply cut out what is needed. But here, the objective is to honor what has been saved, resisting the impulse for speed and avoiding the need for new logging.

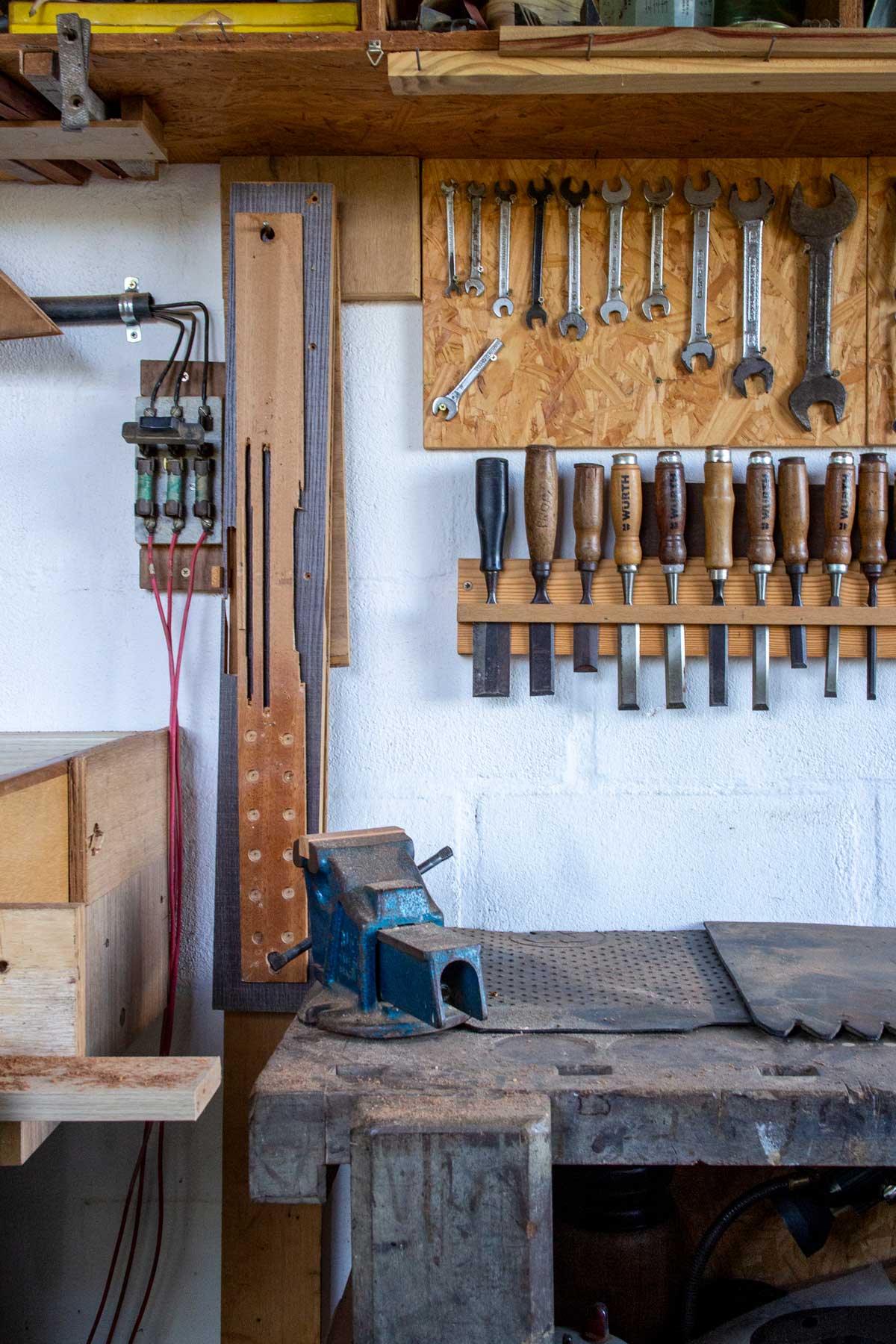

Often, inspiration arises from a technical challenge, prompting me to mentally unfold each stage of the process—questioning the correct sequence of actions, identifying the minimum tools required, and searching for the best available material.

Invariably, the wood fragments differ from the ideal dimensions—usually smaller—which demands adaptation. This phase becomes a mental exercise in anticipating risks and calls for heightened precision in motor coordination.

I begin with a rehearsal, feeling out the critical points and resolving any uncertainties. I prepare the tools and safety equipment, separate the pieces, and align them in sequence, ready for the task ahead.

Then, I turn on the machine and enter a meditative state. Repetition becomes the mantra; precision, the focus. Nothing else should exist.

Step by step: preparation, assembly, finishing.

When the work is complete, a visible transformation occurs—both in the material and the craftsman. There is a sense of having deepened one’s understanding of the technique, the material, and sometimes even of oneself.

Before the endless panorama of the mountains, one is reminded of the vastness and the profound insignificance of it all.

Photos: Christian Sievers