At that time photographs were considered more trustworthy than an individual’s memory, critical to how events could be understood and how histories could be constructed, and a way in which traumas could be made visible and shared. As Susan Sontag had just recently put it, a photograph was “not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real, it is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.” And in the Chelsea Hotel there was much of the real, as well as the unreal and surreal, not only to be recorded but to be interrogated, and ultimately celebrated.

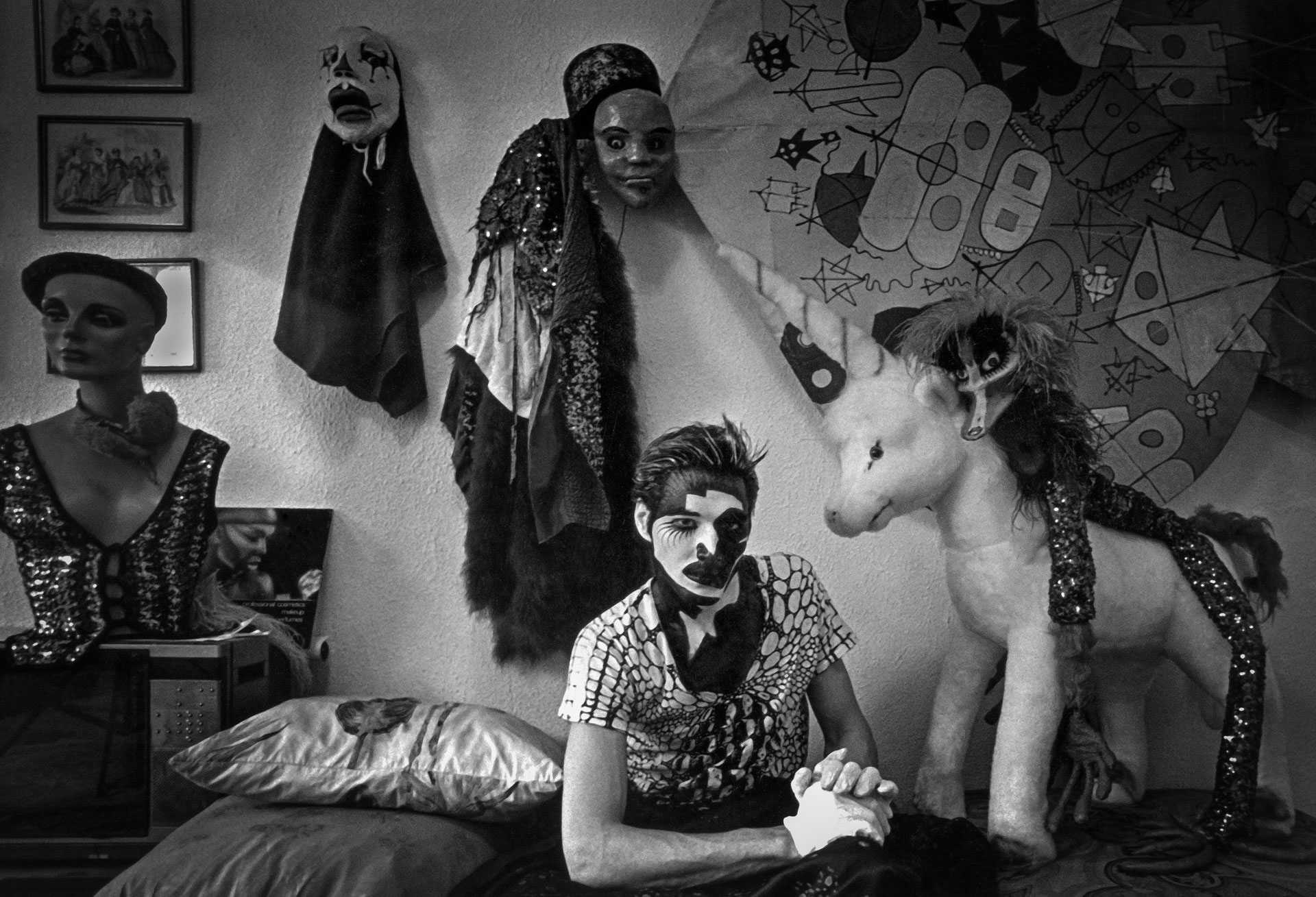

Claudio Edinger, Jimi Hendrix Look a Like, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

New York was not an easy place to be at that time. Chelsea Hotel was first published as the virus that causes AIDS was being identified, its rapid spread ripping large swaths from the city’s arts community, the grief and fear palpable. The essential premise of life—that it could be lived—had been withdrawn abruptly and, it seemed, vindictively. The startling, often endearing eccentricities seen in Claudio’s photographs delineated not only some of the wilder manifestations of the creative spirit, but also marked the moment when certain of these freedoms would be constrained.

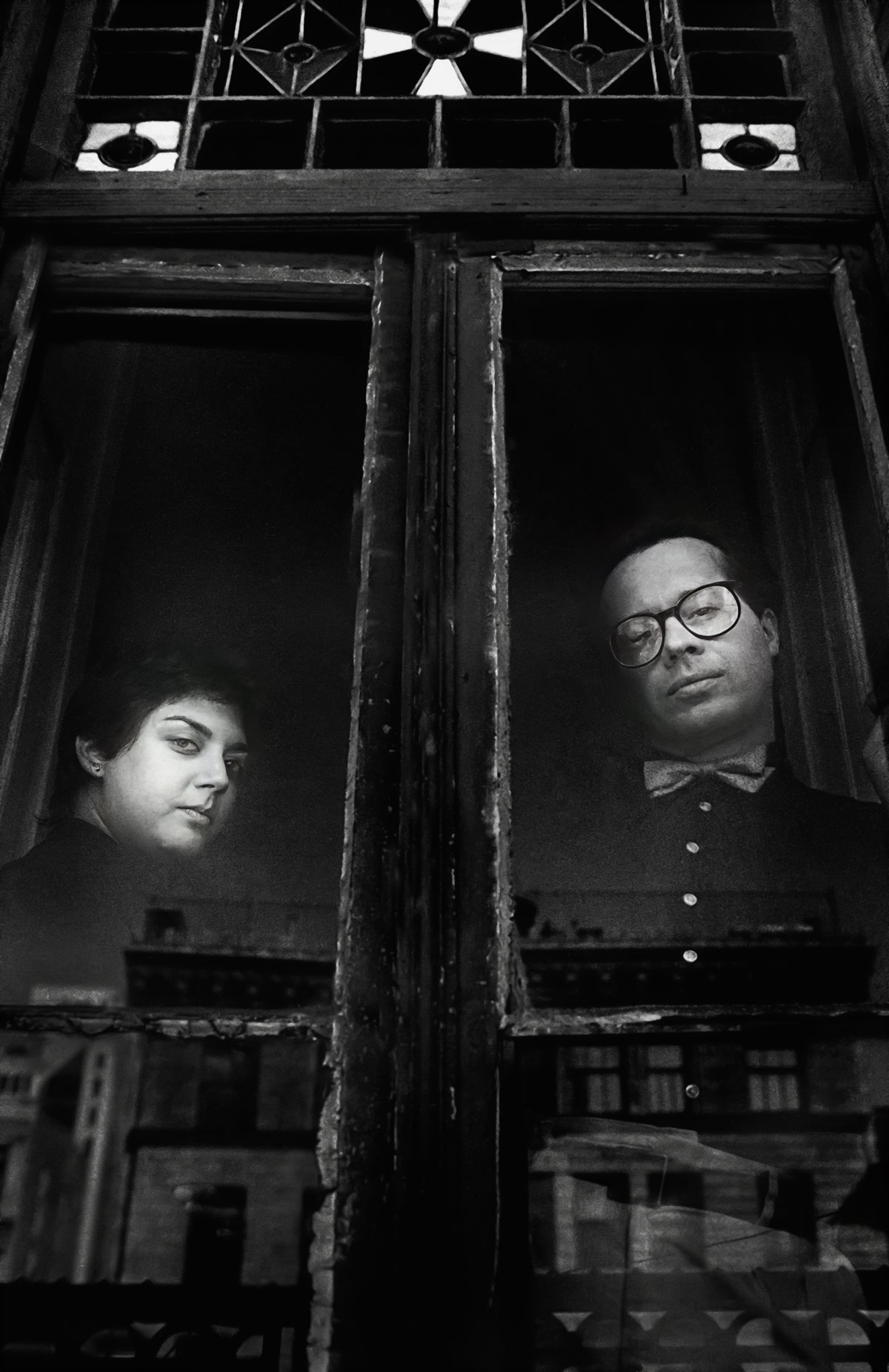

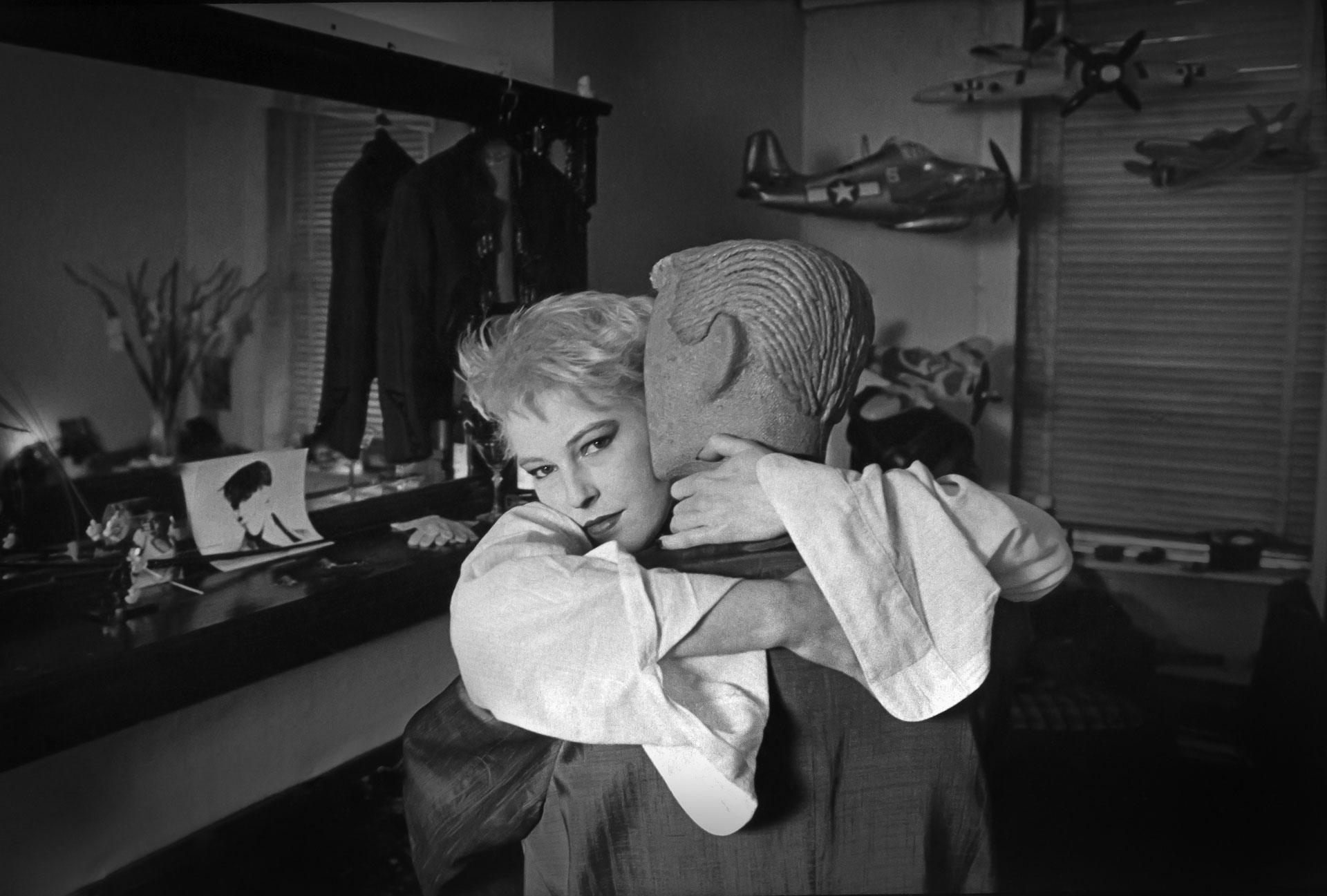

Top left: Claudio Edinger, Cory, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Top right: Claudio Edinger, Don Normal, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Lower center: Claudio Edinger, Birthday Party, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

The book’s publication also coincided with photography’s entrance into the digital age. In 1982, the year before this book was first published, the editors of National Geographic had introduced the undetectable manipulation of the photograph via software, as film was transformed into a mosaic of pixels, using a computer to modify a horizontal photograph of the pyramids of Giza so that it would fit on their vertical cover. Two years later in an interview the magazine’s editor defended the intervention to me, viewing it not as a falsification but, as I wrote then in the New York Times Magazine, “merely the establishment of a new point of view, as if the photographer had been retroactively moved a few feet to one side,” a novel and destabilizing form of time travel. And, with similar software for individual use appearing several years later, such modifications became commonplace, the photograph rendered malleable, considerably less of what Sontag had called “a footprint or a death mask.”

Claudio Edinger, Darrell Mondello, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

Claudio Edinger, Barney’s Birthday Party, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

In the era when Claudio was seeking out his neighbors and asking them to pose, it was not yet the time of “We Are All Photographers Now!” the title of a 2007 exhibition in Switzerland that would recognize the omnipresence of cellphones and their cameras. When Claudio was working at the Chelsea being photographed for one’s portrait was still a privileged meeting of subject and photographer, a collaboration with a potential for both revelation and posterity. As Richard Avedon described it, “a photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows he’s being photographed, and what he does with this knowledge is as much a part of the photograph as what he’s wearing or how he looks.” At its best, the portrait could be a commingling of psyches and souls, as it is in many of Claudio’s photographs.

But that era is no more, disrupted by the billions of selfies and other digital imagery uploaded online. Now, a further, even more transformative change has occurred — the advent of artificial intelligence which makes the photographer, the subject, and even the camera, unnecessary. Instead, it is now possible to generate imagery via text prompts that appear to be identical to photographs, with results in seconds. In a few words one can solicit photorealistic images describing the inhabitants of the Chelsea Hotel of the 1970s or ‘80s, as I did while writing this, depicting people who never existed but who look like they might have been neighbors of those portrayed here. As a result, histories become easily distorted, while every image that looks to be photographic can begin to be viewed skeptically as a potential simulation. The credibility of the photograph as a recording of the visible becomes less assured.

Claudio Edinger, Thomas Patrick and Wendy Gould, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

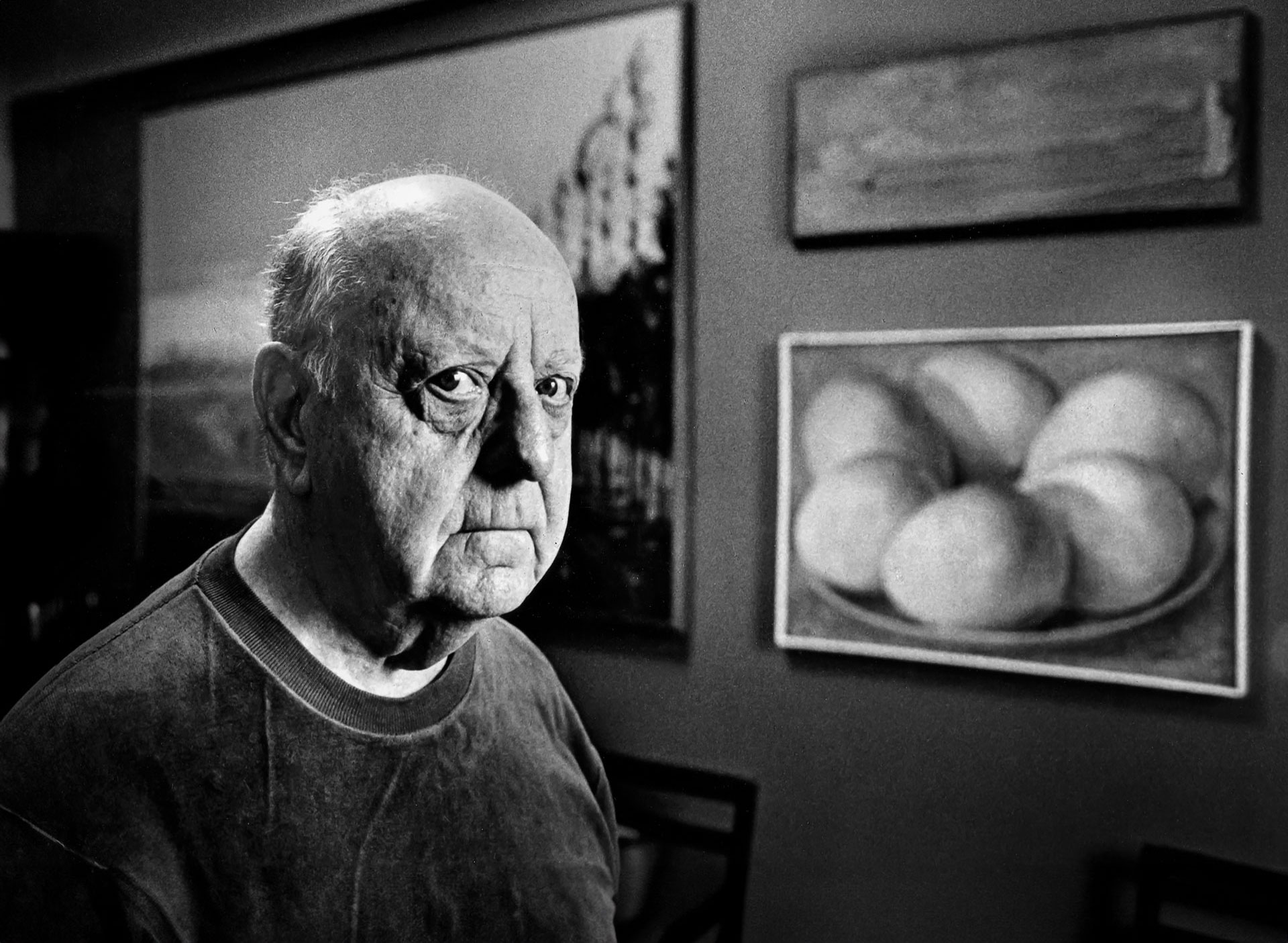

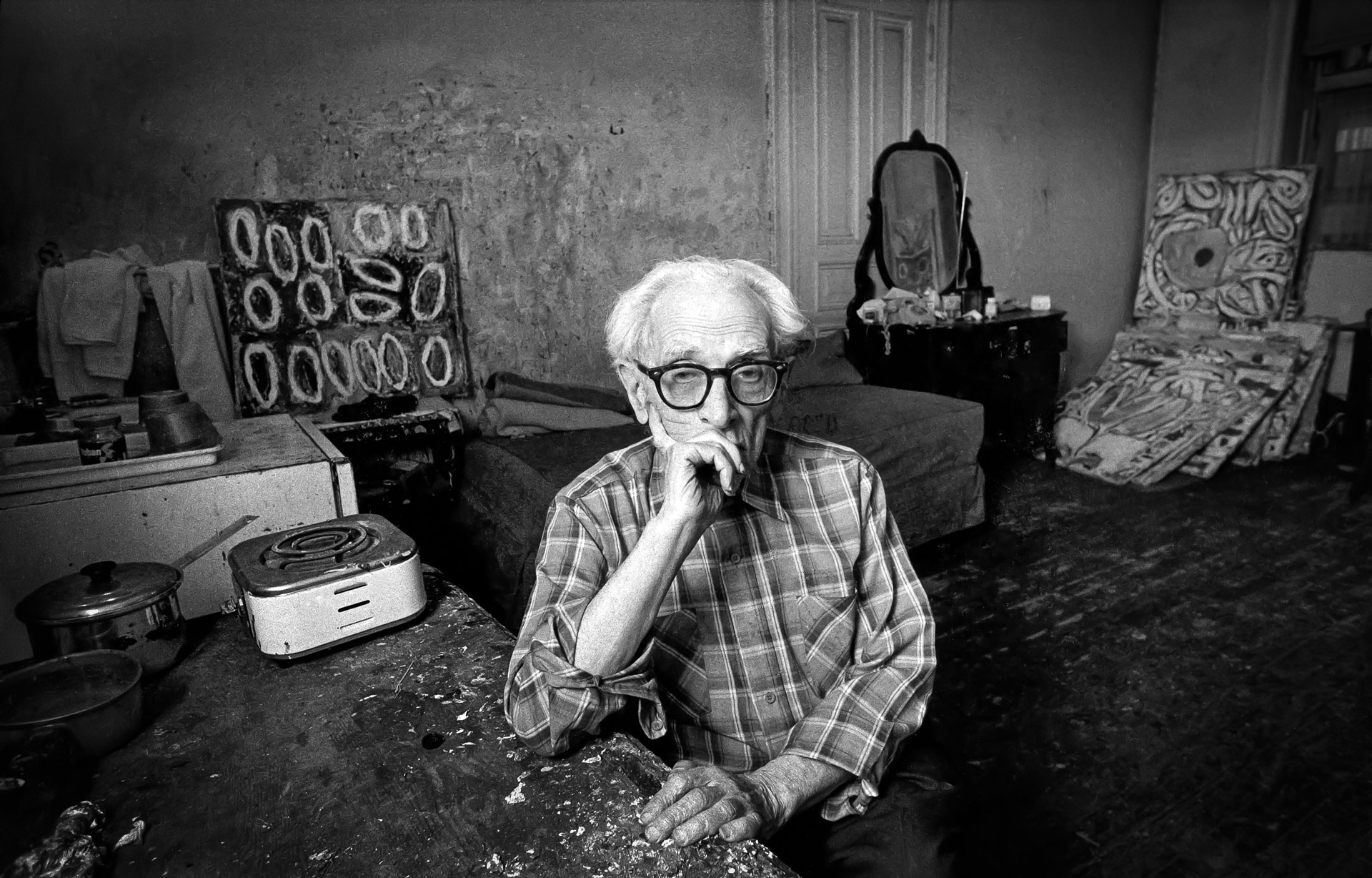

Made on film and processed in a darkroom, bound together as a book, Claudio’s photographs have survived these perturbations, still able to illuminate lives and make palpable the contexts in which they were lived. Decades later a reader is able to acknowledge the reality of the blind couple shown seated on armchairs, the woman having to sing as loudly as she could into the airshaft so that their next-door neighbor, Janis Joplin, would stop rehearsing and they could get some sleep; the writer of two books who finger paints and cleans his fingers on the wall before answering the phone so that the wall itself, as he put it, “is a masterpiece”; the 81-year-old painter who gave a painting in exchange for free rent and later died at the age of 112, the oldest person in the United States; the Jimi Hendrix look-alike, photographed in a hotel elevator, who said “I look more like him than the man himself”; or the record producer posing with his partner, who may have best described life in the hotel: “You smell people, passion. It is evident that artists have lived their problems here.”

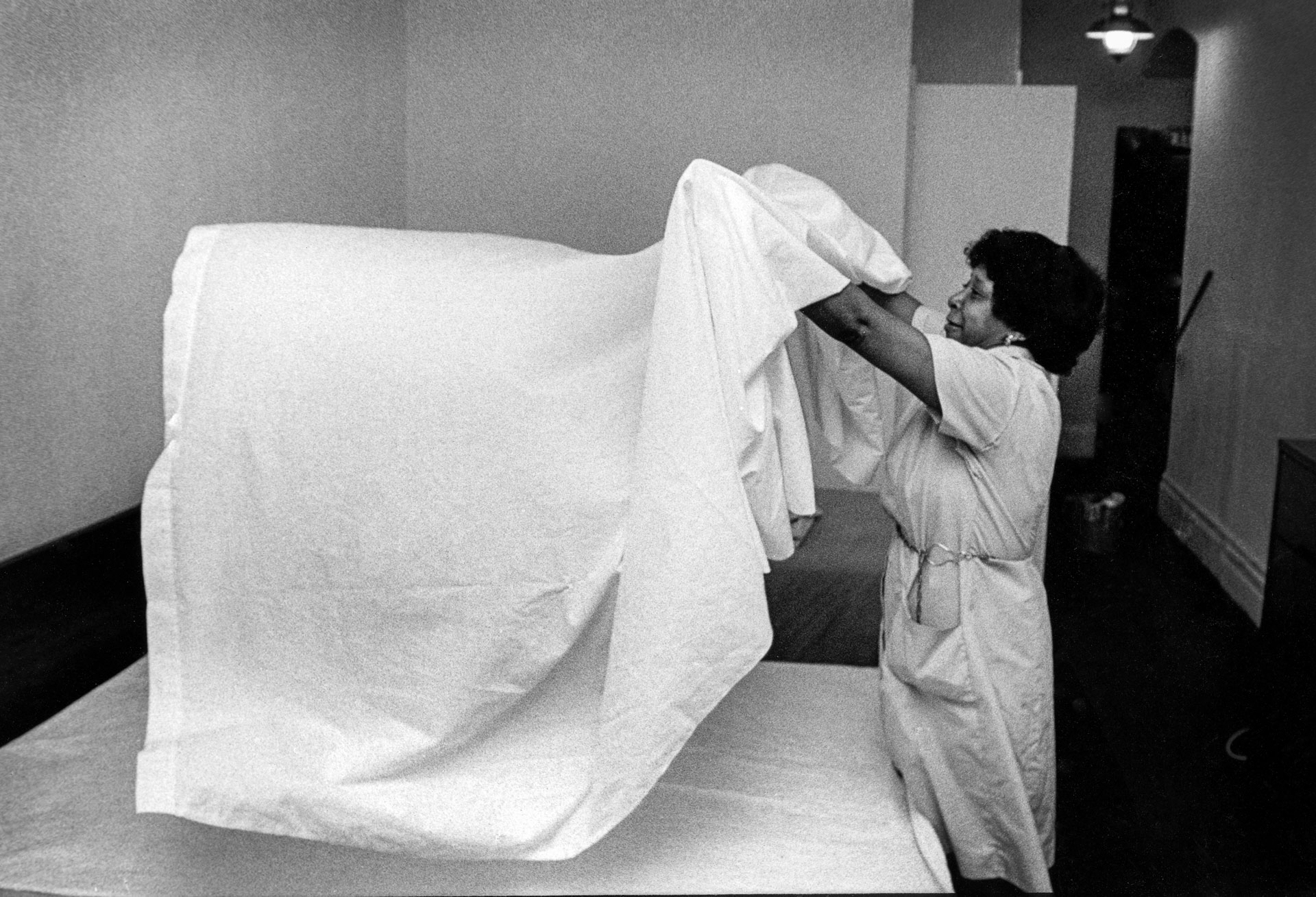

Top center: Claudio Edinger, Alpheus Cole, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Lower left: Claudio Edinger, Cleaning Lady, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Lower right: Claudio Edinger, Bruce Steele, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

Chelsea Hotel frames a moment when it was possible to live differently and intensely in a community of like-minded individuals who would meet and converse with each other in the flesh, not online, and were able to respond to the lens of an intrepid photographer with their own extended gaze. These feelings are still evident today, even when viewed from the perspective of a less tactile, increasingly virtual age.

Now is not then, however: an internet search retrieves a booking website asking prospective inhabitants of the Chelsea, advertised as a four-star hotel, to “make yourself at home in one of the 155 guestrooms featuring minibars and Smart televisions. Your memory foam bed comes with Egyptian cotton sheets. Complimentary wireless internet access keeps you connected…,” while “contactless check-out is available” as well.

Top center: Claudio Edinger, Couple and their bunny, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Lower center: Claudio Edinger, Dan Schock, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print.

Courtesy of the artist.

This, of course, is no longer the same Chelsea Hotel. As is made explicit in the photos and interviews in this book, memories were not to be found in foam beds and “contactless” would have hardly described the ambience. Nevertheless, we can assure ourselves that the souls of its inhabitants portrayed here, the Chelsea’s real treasures, have managed to endure, their creativity apparent, thanks largely to one dedicated photographer on his own spiritual quest. It took a young Brazilian, an outsider himself, to help remember this community of outsiders best.

Top left: Claudio Edinger, Viva, Alex and Gabi, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Top right: Claudio Edinger, Virgil Thomson, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Lower center: Claudio Edinger, Do Chemyns, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

Fred Ritchin is dean emeritus of the School at the International Center of Photography. A noted writer on photography, he is the author most recently of The Synthetic Eye: Photography Trans- formed in the Age of AI, and is also an editor and curator who focuses on projects exploring issues of social justice and human rights.

Claudio Edinger, David Schwartz, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

With a degree in Economics, Claudio Edinger (b. 1952) began his photography career in 1975. He is the author of 23 photography books, a novel, and a book on the history of photography.

He has received numerous prestigious awards, including the Leica Award (twice), the Hasselblad Award, the Higashikawa Award (Japan), the Life Magazine Award, the Ernst Haas Award (USA), the JP Morgan Award, the Pictures of the Year Award (USA), the Abril Award (twice), the Marc Ferrez Award, and the Porto Seguro Award in Brazil (twice).

Edinger’s photographs are part of the collections of LACMA (Los Angeles), Maison Européenne de la Photographie (Paris), MASP, MIS, MAM, MAC, Pinacoteca, Museu Metropolitano de Curitiba, Metronòm (Barcelona), Higashikawa (Japan), AT&T Photo Collection (USA), Equity International Photo Collection (USA), Brazil Golden Art Fund, Itaú Cultural, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Instituto Figueiredo Ferraz, and the largest private photography collections in Brazil.

This year, he was included in Forbes magazine’s list of 50 Brazilian celebrities over the age of 50.

Claudio Edinger, Self-Portrait, 1979-82. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.