Isabella Lenzi: How old is Rosa now, Cá?

Carolina Cordeiro: 1 year and 10 months. Is Nina 1 year and 11 months? Rosa was born on October 23rd, and Nina is early October, right?

IL: She was born on September 30th, so there’s less than a month between them.

CC: They’re the same zodiac sign, right?

IL: Yes. And they both have such strong personalities, don’t they?

CC: They do. But they’re sweet too, aren’t they?

IL: Yes, Nina is a sweetheart, super cute. Very fun. But at the same time, she’s already super bossy.

CC: Totally. Her mom and dad are hers, the world is hers. Not sure if you experience this as well, but has your memory stayed the same since the pregnancy? Because mine… [laughs]

IL: I think we lose about 50% of our intellectual capacity [laughs]. Sometimes I feel stupid. For example, the language thing is really surprising. It feels like my Spanish has become terrible, and I feel like I’ve forgotten English, which I always spoke well. Oh my God, can I no longer speak English? It’s gone, you know? Disappeared. These things just vanish, and you don’t know where they went.

CC: It’s crazy because it feels like there’s this plasticity of the brain that changes a lot after you have a child. And then I wonder where it all went. Obviously, a lot of it goes to the child because we’re in this daily caregiving mode, and breastfeeding is so exhausting. There are so many factors and things happening that no one really talks about, right?

IL: Absolutely. I keep thinking about our industry… Maybe you have some flexibility in your work, but there’s still this constant demand, this expectation of what we have to do, and it reflects how society in general doesn’t understand what we’re going through. You’re in a project, and people are asking for answers all the time, at any hour. And you’re with your child, feeling awful because you have to respond and can’t, and at the same time, you need to play with them but can’t. I feel like I’m constantly stuck in these tough moments, where I’m neither fully present with Nina, giving her the attention she needs and deserves, nor fully able to do my work well. It’s so frustrating. All this talk about listening, empathy, care… It’s all nonsense, just talk. Because in the end, the art world is harsh, competitive, and cruel. You slow down, but others don’t. So, there’s this internal work of understanding that I’m in a different phase, gaining other things, building new things. Different experiences, learnings. And this slower pace will come back. Or maybe it won’t. Maybe it’s better if it doesn’t because you also realize it wasn’t very healthy.

CC: It’s such a radical change. Life has taken us into very different situations from our previous routines. I see the world in a completely different way now. In my case, my work has changed drastically because my relationship with time has changed. Before, I didn’t realize it, but I had a very expansive experience of time. And now, I don’t. I still haven’t fully understood what’s happened to my memory, but some responses have to be quicker. At the same time, in certain projects, it seems like some answers come faster because you know you won’t have time later. The gaps we have are counted chunks of time. That’s why it took us so long to have this conversation, right? If I don’t use this half-hour, and Rosa wakes up, I don’t know when I’ll get another half-hour like this.

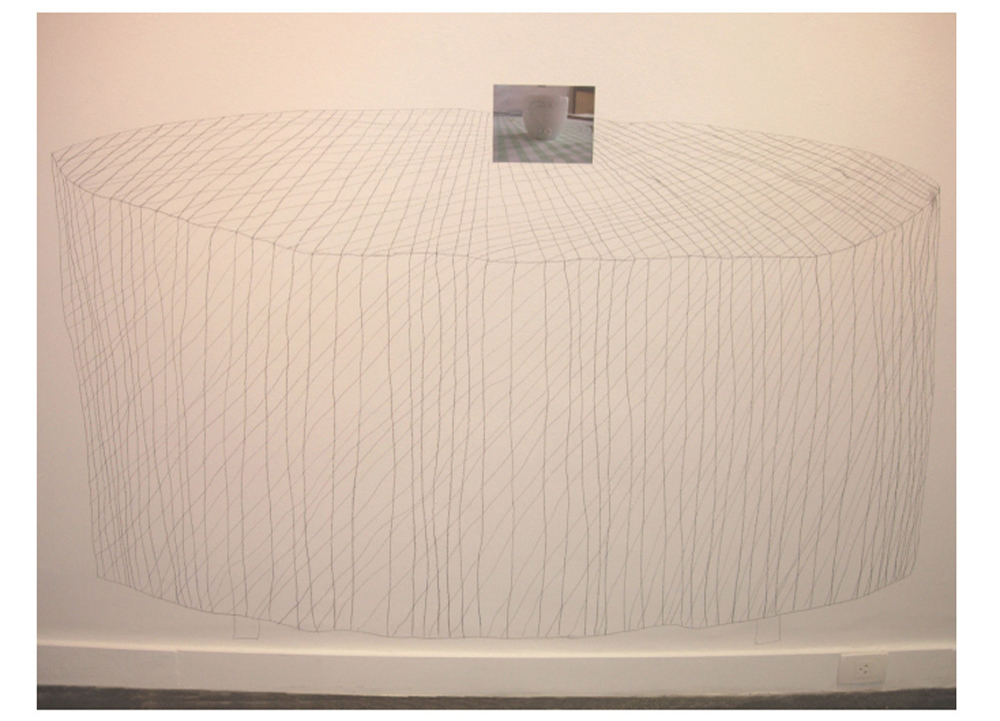

Carolina Cordeiro, o tempo é (the time is), 2023. Exhibition view. Photo: Ding Musa. Courtesy: Galatea Gallery, São Paulo.

IL: I’ve been wanting to talk to you about all this for a long time. There’s something you said that I find fundamental, something that really resonates with me and interests me deeply. I’ve seen exhibitions about motherhood, in São Paulo and also in Pamplona, and it’s a theme that many female artists address in their work. But for a long time, it was absolutely invisible, right? In art history, in the art system, in the art circuit. And even with these projects, I think that this first-person voice, as you described it—this feeling of losing a large part of your memory or feeling that part of your intellectual capacity has transformed—that these are things that aren’t normally addressed, right?

CC: I think almost nothing is addressed, and everything comes as a big surprise. We live in big cities, and we’ve lost some of that connection with mothers, grandmothers, and the wisdom that used to be passed down more routinely. We’ve become isolated, living in small units, without that larger network that used to warn and help us understand things more empirically, in a more tacit way, about how things unfold. We end up having to figure it all out on our own, right? And I think this ties into capitalism. You can’t say that it’s hard and that you need help because you have to be this superwoman in order to not lose your place. And I’m not even really talking about myself because I’ve given up a million things. I’ve missed all the events, gone to almost no exhibitions, simply because I just can’t. I don’t have the energy. And this relationship with… oh, I was just interrupted by a baby’s voice, and now I’m trying to get my thoughts back [laughs].

IL: That’s interesting. And I don’t want to interrupt you either [laughs], but I want to comment on this issue of wisdom being passed down and the support network that’s not just about help, but also about sharing responsibility and being collectively accountable.

CC: When it comes to caring for a child, one father and one mother isn’t enough. We manage the basics—keeping the house and life in order so that the child can grow up happy and healthy, and all that. But continuing with artistic production is really tough, very heavy. And we don’t have another option, so we don’t stop working for even a minute. We have to keep going. I don’t know what your experience has been in Europe or how the cities are designed to accommodate children there, but sometimes you feel really violated living in a big city. When you leave the bubble of the first three months of the baby’s life… you step outside with this tiny little life in your arms, and you’re faced with this giant São Paulo, with everything going on. It’s very aggressive.

IL: I think there’s also a shift in our perception of the fragility of things and the hostility of public spaces. When people ask me what changed in me with motherhood, I say that, in some way, I feel like I became more human. I can’t help but think about issues of diversity, for example. The first time I went out after having my baby, here in Madrid—which is a city much easier to navigate with a stroller than a city like São Paulo—I felt fear when a car, a bicycle, or a motorcycle passed by. And ever since, I’ve thought about what the experience must be like for someone navigating the city in a wheelchair or for a person with visual or hearing impairments. Cities are very violent spaces and not at all prepared for any kind of fragility or sensitivity. And I imagine that, while we may lose a bit of our ability to focus or remember, because our work is so grounded in sensitivity, we gain other things. We’re talking about motherhood because that’s what we’re living, but these gains could come from other experiences, like an illness or a family issue, which transform our intellectual, artistic, and sensitive production, right?

CC: That’s really nice. Because, in the end, what truly happens is an expansion of sensitivity. We start accessing a place we didn’t know before. I never thought about how my work was affected by motherhood beyond the relationship with time. And indeed, there’s a lot of this expansion of sensitivity and empathy towards the world. In my work, I’m not going to talk about childbirth, my belly, or my body. That’s not related to what I do, to my language or my field of thought. I leave that to other artists. But this deepening into the field of sensitivity, the observation of walking through a city… I like this focus on the landscape that surrounds us, on an intimate landscape that connects to a public space. I think this might have been activated by the experience of motherhood. I don’t think it will directly appear in the work, but this deepening, in a way, makes me a part of it. In your case, do you see it appearing directly in your work?

IL: I think there are two different moments because curatorial practice is different from artistic practice, right? But I do feel that, often, exhibitions lean toward themes like childbirth, the experience with the child, or the need to give things up because the world isn’t prepared to accommodate either the child or the mother who has just had a baby. These spaces usually deal more with this aspect, this kind of invisibility of the mother. But they may deal less with this other side, which is very beautiful—the empathy, the different relationship with time. These are more subterranean, less obvious issues that relate to what you’re saying. And this won’t necessarily show up directly in the work if your work manifests in a more poetic realm, with small interventions and small transformations. So, as I was listening to you talk about time, I found it funny because I feel like your work already had a lot of that essence, you know? And perhaps motherhood made that even stronger. I was looking at some of your pieces in preparation for this conversation and also thinking back to projects we’ve done together, and one of the things that’s fascinated me about your work from the beginning is being able to see what happens with a small action—working with surprise, with the unpredictable, with what happens through the laws of physics or the circumstances of a specific moment in a specific place. And I think there’s a sensitivity to that too, a kind of listening to the place and the moment. So, if you’re telling me that with Rosa this is heightened, I think: Wow, then it’s going to get even better!

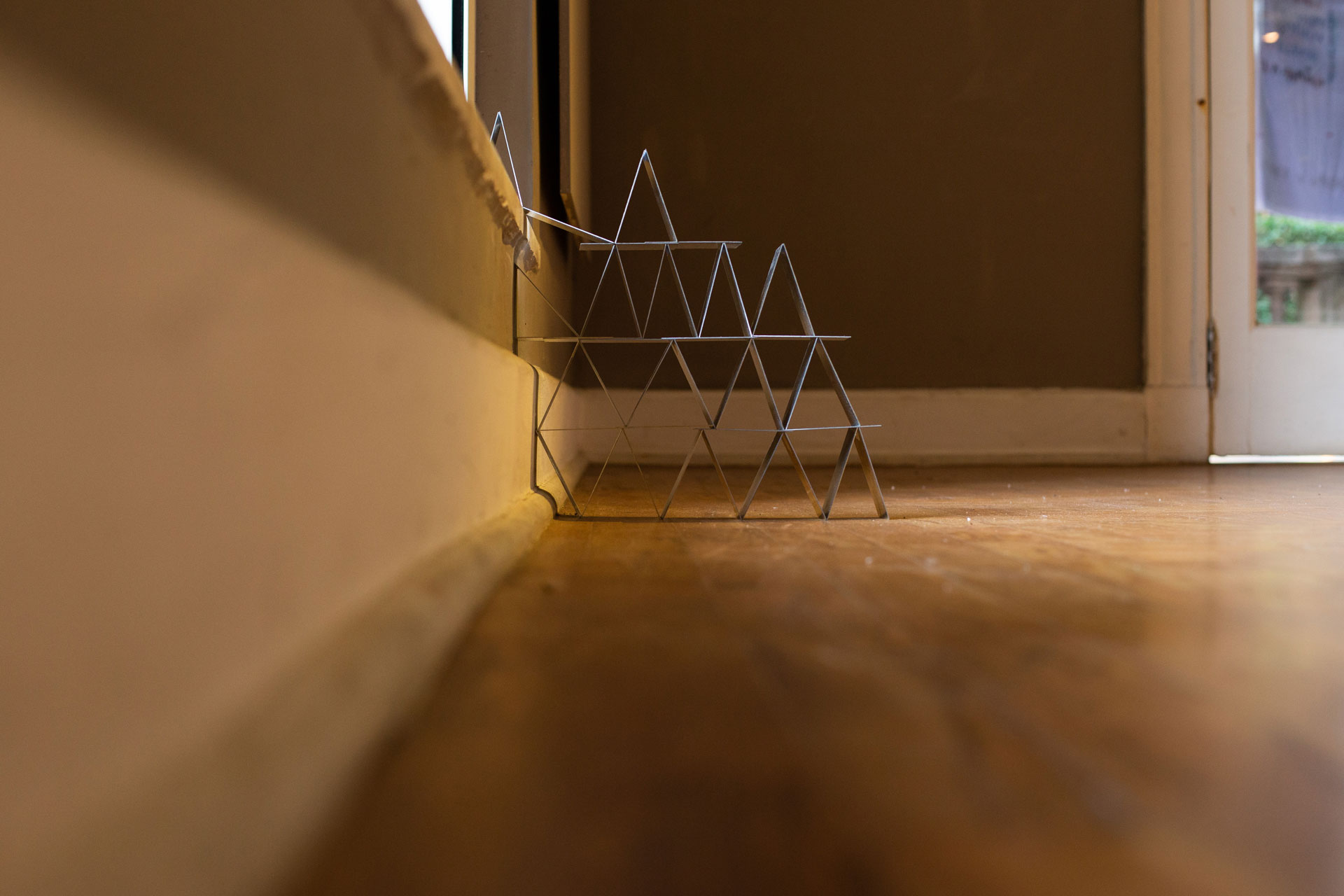

Carolina cordeiro, Untitled, 2019. Zinc plates, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

CC: Where will all this go now, right?

IL: But I’m sure it will lead to many places. Because, in fact, we experience space and human relationships with a new intensity.

CC: I think that’s it. It’s a presence that happens more sporadically because we have fewer opportunities to be in places, at exhibitions, doing the things we used to do. But maybe, due to the impossibility of extended time, we end up having a more intense presence where we are. And maybe this shows up in how I work, because my mind is orbiting around millions of other questions that didn’t exist before, and maybe through this new experience, I’ll visualize something different, something that could be a new project or a desire to explore. Time is the key because it transforms perception. A baby isn’t a linear experience. They live in cycles. You think you’re going one way, and suddenly, you’re backtracking or heading in a new direction. I think time is like that too. During the pandemic in 2020, sometimes I felt like the days were too short and flew by, and at other times, it seemed like the day would never end. So, I think it’s also about understanding how time is elastic and malleable, just like our brains. Maybe everything is the same thing. The same substance that time is made of might be what we are, too. And maybe I’m just realizing that. I’m really going off on a tangent here.

IL: Totally. At the same time, this experience is about measuring time—what happens every week, how many weeks are left, the developmental stages. But it’s also what you’re saying about time being elastic. Life is so much like that, right? In some way, what we’re saying about motherhood could also be said about the absolutely crazy and dystopian experience of the pandemic. I think it’s something we could have learned a lot from, but I feel like there wasn’t really enough time for people to fully grasp many things.

CC: I don’t know if it’s because there wasn’t enough time. I think we live in a system that doesn’t tolerate pauses. The world sped up a lot after that period. As if we had to make up for lost time. It’s over! No one’s going to sleep anymore; everyone will work 24 hours a day, and social media will get even more intense. That’s where the dystopia begins, and it keeps going. And maybe our decision to have children after that event is something really wild, right? Maybe it’s actually a desire for life.

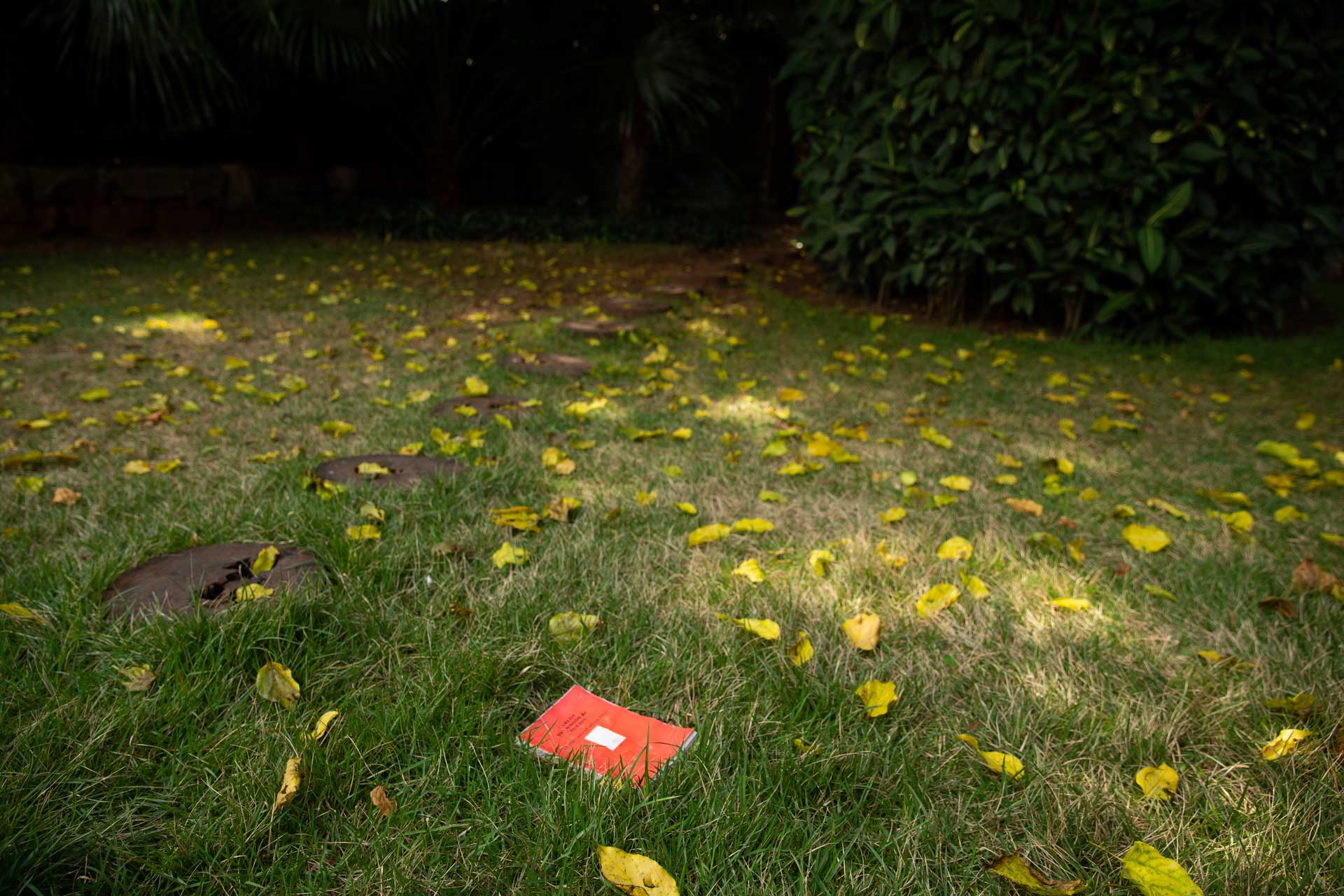

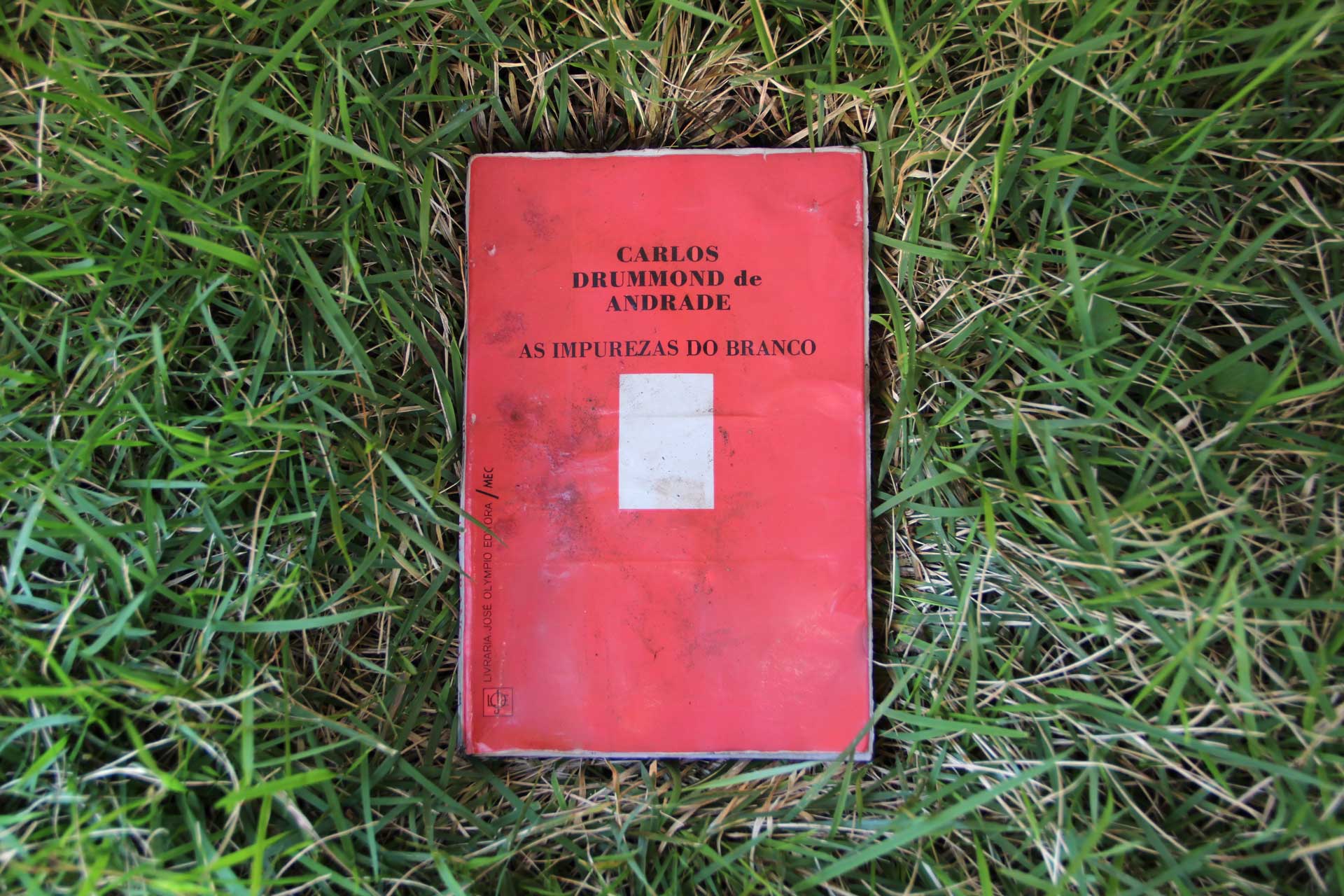

IL: And also a desire for a pause. In my case, I had the desire to have a child to experience a different kind of life and connect with things in a different way. Because there’s also the slower pace of childhood, which we understand as a time for learning and discovery. We are in a fast-paced time, but children are on a different timeline. Does a child need to finish eating in five minutes? No, the child will eat at their own pace, and you’ll have to wait. You can try to speed things up, but we already know that usually doesn’t turn out well. There’s beauty in that. And I see a nearly direct parallel with your work, which also involves the time of observation and transformation. For example, I was revisiting As Impurezas do Branco, which, like your other works, has its own time to unfold and isn’t complete from day one. It needs time to pass, days to go by, for the rain to wet it, the sun to burn the page, the grass to change color, for you to have the possibility of transformation and to leave a kind of trace. Your work is full of traces, of what remains, of what falls, of what decants. And decanting is time, right?

CC: Yes. In some way, I’ve always resisted that acceleration. And I propose these works that are actions that don’t depend on me but on the time of nature, where the object stays there for a period until something happens. And it won’t necessarily work if I want to speed it up or have it ready by tomorrow. You mentioned As Impurezas do Branco, a work I rarely talk about but really like… I remember when we opened the exhibition, it couldn’t have been with the finished piece. There was a garden at the consulate, and the book was on the grass, and someone saw it and thought it had fallen or been forgotten, so they took the book from the garden and put it on a little ledge [laughs]. Luckily, I saw it and returned it to its place. Just like those little zinc castles, they are works that can be undone depending on the encounter with certain people. And that depends on decanting, but there’s a quality that’s very sensitive to the actions of others. So, both the little castle that could collapse because it was just supported by cards, and the book that could be removed from the garden and not unfold, right?

IL: Or unfold in a different way. This element of surprise, lack of control, and chance… that’s very present in many of your works. Your work has this subtle and poetic side we’ve been talking about, but at the same time, it’s very sharp, very precise. Because things aren’t accidental. So, the cards in that little castle aren’t playing cards; they’re zinc sheets, and there’s a whole historical context around a specific kind of construction and a very specific type of society as well. Similarly, you don’t just grab any book and put it on the grass—you choose As Impurezas do Branco, Drummond’s book. So there’s a process behind getting to the small details of these actions or interventions or these poetic objects you create.

Carolina Cordeiro, As Impurezas do Branco, 2019. First edition of Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s book left on the grass. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

Center and lower image: Carolina Cordeiro, As Impurezas do Branco, 2019. Photographic diptych – First edition of Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s book left on the grass. Courtesy of the artist.

CC: I think it’s all part of a very in-depth previous research. That’s a characteristic of mine because I’m also a researcher. But I’m not talking about a specific academic study; I’m talking about a way of being, of being in the world. And when I bring this to my work, I try to do it succinctly. So, I look for a form of synthesis, but to reach that form, there’s a research process involving many years of observation and historical knowledge, which interests me a lot. The works are the result of a decantation. That’s a beautiful word you used.

IL: Yes! Because I think there is also, in the process of decantation, an idea of separation. Like when you pour beans on the table and start separating and choosing the ones you want. And I liked that you mentioned synthesis. Your work really has a very acute power of synthesis and a capacity to speak about many things in a simple way, not because it lacks complexity, but because in this process of decantation and investigation, you use very everyday materials, as you did with the shape of the cake.

CC: Everything is loaded with a series of elements, whether they are affective, memories, or also observations of the surroundings. But I try not to transform anything into an autobiography. When I bring the cake shape with the geometric designs made with flour and oil, that can be accessed by many stories and many people who come and stand before an object that makes sense to them or just as an ordinary thing, and that’s fine. But I say this because sometimes it’s a bit dangerous to talk about this thing of affection in contemporary art and turn everything into a big ego, a big self. I bring many elements of a particular and affective story mixed with an observation of the surroundings and the world, and the thing expands beyond the symbolic and objective house, going out into the street, into the world, and so on. Because I think that’s where I can synthesize. That’s what interests me: a synthetic thing, an object that shows a simple action but can say other things. I think it’s a bit like that.

IL: I find it interesting that you mention the ego. As much as artists want to believe that their explanations of their works define them, we know that’s not how things work. The moment they’re in a public space, these objects will be read in very different ways, depending on the geographical context, social context, the age of the person, their experiences, their references. All of this changes a lot. In your work with shapes and in others, there is, even if indirectly, an almost ironic or critical relationship with art history and particularly Brazilian art history. So, in this specific case, there’s a whole relationship with a geometric heritage, with a particular way of making, but starting from elements that wouldn’t typically be used to create this type of work. For example, Mira Schendel, who worked at her kitchen table, but not just at the kitchen table, like with the cake shape, the flour, the oil. So, let’s say you take it a step further. And it’s also a very accessible work. The card castle, the cake shape, are works we connect with through a fascination—that’s why I call them poetic objects. I feel that you don’t need to go further, but if you want to, there are many layers there to access. And they are very sweet in that sense. I’ve always felt that way about your works. This word ‘affection’ seems very problematic to me because now everything is affection, right? And when they say, ‘this work is clearly made by a female artist,’ I wonder: what is a work clearly made by a female artist? I don’t want to go down that path, but I’ve had discussions with artist friends whom I love, and they would tell me they criticized other female artists for working with copper or steel, as if they were materials that women shouldn’t use, but with a whole feminist discourse. And I think just the opposite, you know?

CC: I find that statement frightening.

Carolina Cordeiro, Untitled, 2009. Aluminum baking trays with flour and oil designs, first version 2009 (still in production). Photo: Ding Musa. Courtesy of the artist.

IL: Yes, I think women should work with whatever materials they want and not just what is given or expected of them. So now there’s this whole wave of textile art, which I think is wonderful and all, but it speaks of work in the realm of the sensitive, the affective, the collective, as if only women could work with these things. So, in that sense, I don’t want to say that your work is feminine. When I talk about sweetness, I don’t want to go down that path. But I feel that it has a very particular sensitivity and an understanding of the world from a very human, very empathetic perspective.

CC: I think it comes from a very particular story. From my body moving through the places I have been. When you start producing, you face a series of obstacles: financial resources, access to places. And I think this was fundamental for me to direct my gaze to what was very close to what I could grab and access. What could I have in my hands to finally make the work that was urgent? The work that was there in that very young person with a strong desire to create. So you can’t wait to have money to buy expensive materials. I realized that working with what was in my surroundings was what I could do, and that I could say a lot with such work. You speak of your experience, which is very particular yet quite similar to the experiences of many other people. And we come from a context of Brazil, right? Brazil is very diverse, but everything here has a lot of layers, so it cannot be flattened. I am a Black woman, an artist, who does experimental work, which has conceptual aspects involved precisely because I didn’t want to work with a more academic language, which was what was being done in my university. At the same time, I didn’t have much resource for expensive materials. I think the first works say a lot about what we are made of, who we are, where we look, and why we work with this. One of my first works was made with broken objects that I found at home. I completed these broken pieces with drawings and photographed them. Then, I enlarged these small photos and continued the drawing on the wall. So it became a small installation: a drawing that continued inside and outside the photo. An object that was broken but continued to be used at home. Just because something breaks in a middle-class house in Brazil doesn’t mean it stops being used or is replaced, because that family has specific resources. So, what I want to say is that there are many layers, and the experiences are very defining of what you present, where your work goes, and the transformations it undergoes. But I think all of this is there, you know? I respected this path and arrive at a synthesis because I accumulate a series of experiences and I expect that decantation and understand a form to present this to the world.

IL: I think we’ve never talked about this. When you talk about generation, I’d like you to tell me a bit, if you can, about what people around you were doing when you were an art student. And then, when you say you are a Black woman and an artist, was that something you thought a lot about back then? How did you see yourself as a Black woman from a middle-class family in Minas Gerais, in a country like Brazil, within the art circuit?

CC: That’s a great question, actually, because I think everything is very boxed in the history of art and more recently in the art market.

IL: When they put you in a box, they expect a specific kind of work from you.

CC: Exactly. And I don’t fit those boxes. So nobody really knows where to place me. I’ve always had an interest in my surroundings, and there was already a little group around me that was doing more experimental work. Paulo Nazaré was already in college when I entered, and he is a great friend to this day; he wrote the text for my exhibition and so on. I remember seeing his first solo exhibition, which was in the entrance hall of a theater, a horrible place to have an exhibition, and he managed to put things he had found along the way and did a performance where he played capoeira too. It was a super beautiful thing that left a strong impression on me. Experiences like that made me understand the power of working with what you have close by, with what you have direct access to. However, in art history studies, I had no reference to Black women artists who had conceptual and experimental works. Today, yes, I know a few. I still consider them few, especially in Brazil. I’m 41 years old, but in the younger generation, I already see a lot of artists doing incredible things, putting ideas into the world with real, strong, and impactful experimental projects. In that sense, I felt very out of place from what was expected of an artist with my characteristics. But I kept doing it. I think in this case, curating must have some similarity with artistic production. You simply don’t change the subject because a subject is in vogue. You keep doing your work and will understand, after a few years, what will happen with it. Since I came from a generation that, due to the first and second Lula administrations, had more public resources for experimental artists, this contributed a lot. We didn’t have to rely solely on the market. In fact, I was in Belo Horizonte, so we didn’t even know what the market was. So, in a way, this preserved my work a lot, and my production was very free from external impositions. Additionally, at that moment, Belo Horizonte (the capital of Minas Gerais) had a very vibrant public cultural life, and that is a very important part of my training too. We would leave the samba circle and go to a theater in the square or watch an MC duel under the overpass. It was a diverse and completely free experience. I’m not just talking about direct influences from a specific artist but about a very lively and accessible scene that was the result of public policies. So, I think that’s what makes my work what it is, alongside my passion for literature and poetry. I think each artist comes from a specific context and it’s never just one thing. It’s a kind of ground that forms for you to step on and understand who you are. I think that’s why I continued doing very experimental work, far from the market program, and I continue to do so today. I don’t know if I answered your question.

Carolina Cordeiro, Untitled, 2005/2006. Digital photographic series, 16 x 24 inches each. Courtesy of the artist.

Carolina Cordeiro, Quase é um lugar que existe, 2006. Digital photography and drawing with graphite on the wall, variable sizes. Courtesy of the artist.

IL: Yes, you answered everything and more. Because you touch on many issues. One of the things is even a boring topic, but inevitable, which is the perversity of a system that is not only about the market but also about public policies. I think it is essential for the public to understand its function and role in society, so that the public never enters the logic of the market, you know? In the art world, there’s a kind of inversion where the market determines both the subjects and the timing, and as a result, many things are left behind. When you say that there were very positive years when there was public support that made it possible to produce and experiment without depending on a market logic… this is absolutely fundamental for artistic work.

CC: Yes, research is very important. And not depending on a sale. When you are starting out, it’s the time to experiment and do everything until you find your way. And if you start thinking you have to sell… that’s also a possible place; I don’t criticize it because we live in Brazil, a very difficult country for making art, and being financially stable is crucial. But if you have the chance to also understand the place you belong to, what you want to do, and what your references are, that’s wonderful. I think the great utopia is that everyone can have the chance to discover themselves and do what they like because then art becomes powerful, right? Then it communicates in a very real, genuine way, and it transforms.

IL: And I think this goes beyond the market because it’s also problematic when institutions demand and expect certain things from artists. It’s essential in this conversation when you talk about the boxes. They are necessary for affirming minorities that have been silenced for a long time, but it’s problematic when a female artist, an Indigenous artist, or a Black artist has to do certain things because it’s expected of them. In doing so, we reproduce a perverse logic that places these bodies in situations of vulnerability and violence, imposing something on them. And then there’s another thing you mentioned, which is the difficulty of surviving in a country like Brazil. You asked me about raising a baby in Spain, in Madrid, and we could have a long conversation where I could tell you about the various problems and issues I face here, especially those arising from the fact that I am not Spanish and am a Latin American woman living in a colonial metropolis that continues to think like a failed empire but doesn’t see itself that way. We could talk about that, but there are various privileges in living here. I maintain a very close relationship with Brazil due to work and can travel there frequently, but every time I go, I am struck by the prices of things. It’s a very suffocating society because of inequality. So, surviving in Brazil seems very complex to me.

CC: And it is very complex indeed. We live in these dualities. It’s very complex, but it’s still a place where we fight to make things better and easier.

IL: I found it very beautiful that you mentioned this formation that comes from collective learning in a public space with free activities. And in that sense, when I’m in São Paulo, for me, going to Sesc is a bit about that—seeing a bit of the Brazil we want. It’s a project that thinks about the collective, about the public, for people of all generations and different social classes. We want this type of space to exist in a broader way, right? Not just there.

CC: Exactly.

IL: Another thing I wanted to ask you about is the relationship between your work and Minas (Minas Gerais, a state in southeastern Brazil). How do you deal with this issue, considering that you are currently living as a nomad, frequently changing cities? Does this transform your work in any way?

CC: Yes, it always transforms. I just don’t know how yet. I think I’ll only know when I pause for a bit, but it definitely transforms. I gather certain things, even if it’s just visually gathering experiences. And this certainly becomes something else when I create a work. Because it’s very different from a landscape you see every day and have a daily, everyday relationship with. And suddenly things change; places change, and you make another record. But I confess that I still don’t know what this will lead to; I’m curious [laughs].

Photo: Ding Musa. Courtesy of Galatea Gallery.

IL: How do you go about recording your observations of what’s around you? Do you have a notebook, take photos, or just keep it in your memory? How do you organize yourself?

CC: Well, I keep a lot of things in my memory, which is actually a problem because it doesn’t turn into a physical record. For the past few years, I’ve been keeping journals, not necessarily as a work project, but they hold things that can sometimes turn into works. However, I have difficulty taking photos. The photos never turn out as I expect, and now with a child, it’s a matter of grabbing my phone and putting it in my bag… it gets confusing for me. So, I don’t do much recording. And the journal is sporadic as well. I don’t sit down and write every day, but I do it when I have a little time. When I wake up a bit earlier or when Rosa goes to sleep a little earlier. I think that’s been my most consistent method. But memory is still a great source for me. And going back to the beginning of the conversation, I’m relying a lot on memory for someone who said they lost their memory after having a child [laughs]. But it’s still my ally in artistic processes.

IL: And the beauty of memory is that it also transforms things. We reach a point where we can’t tell if certain things are as they are or if we’ve absolutely transformed them.

CC: I don’t know if it’s memory or if it’s fantasy, right?

IL: Exactly. There’s no need for documentation. It’s something that exists in another realm. In the realm of the fantastic or the subjective. I can’t quite say. But, you know, it’s always beautiful to listen to you. I think having calm conversations with people is almost like a gift.

CC: It’s always very good for me to talk with you too. I miss our meetings.

IL: Send me a photo or a video of Rosa?

CC: I will! And I want a photo of Nina too!

Carolina Cordeiro, Sinais iniciais VIII, 2023. Zinc discs and paper, 34 x 38 1/4 inches. Detail of artwork. Courtesy of Galatea Gallery.

To learn more about Carol’s work: @_carolina_cordeiro // www.galatea.art/artists/34-carolina-cordeiro/

Recent Solo Exhibitions: O tempo é, Galatea, São Paulo (2023); América do sal, GDA, São Paulo (2021); Dizem que há um silêncio todo negro, Auroras, São Paulo/SP (2019).

Recent Group Exhibitions: Eterno Egito, Casa Museu Eva Klabin, curators Helena Severo and Douglas Fasolato, RJ (2024); Galerie D’Artistes, GDA at Espaço ZSenne, Brussels, Belgium (2024); Pessoas Negras São O Silêncio Eles Não Podem Entender, GDA, SP (2024); Warm sun cold rain, Galpão Cru, curators Julie Dumont/The Bridge Project, SP (2023); Andar pelas bordas: bordado e gênero como prática de cuidado, Arte 132, curator Lilia Schwarcz, SP (2023); Casa no Céu (para Rochelle), Galeria Vermelho, SP (2023); Obscura Luz, Galeria Luísa Strina, curator Kiki Mazucheli, SP (2022); Semana Sim Semana Não – Paisagens, Corpos e Cotidianos entre um século, Casa Zalszupin, curator Germano Dushá, SP (2022); Lenta Explosión de una semilla, curator Isabella Lenzi, OTR, Madrid, Spain (2020); I Remember Earth, curated by Beatrice Josse, Magasin des Horizons, Grenoble, France (2019); Estratégias do feminino, curated by Fabricia Jordão, Farol Santander, Porto Alegre, RS (2019).

Art Residencies: Casco – Programa de integração arte e comunidade, Rio Grande do Sul (2021); Pivô, São Paulo (2019); Red Bull Station, São Paulo (2016); Homesession, Barcelona (2011); Glogauer, Berlin (2009).

Carolina Cordeiro, Sinais iniciais VIII, 2023. Zinc discs and paper, 34 x 38 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Galatea Gallery.

To know more about Isabella:

In Brazil, she directed the cultural center of the Instituto Camões/Consulate General of Portugal in São Paulo for seven years, consolidating it as a space for debate and experimentation, with a program of exhibitions, public events, and the publication of artist books and catalogs. The goal was to work in a localized manner, mapping, supporting, and promoting the cultural production of both emerging and established Portuguese artists and thinkers through a dialogue with the Brazilian and local context, with an approach that revisited the shared colonial past and present of both countries. Previously, she worked at the Cuenca Biennial in Ecuador (2011-2012) and was part of the curatorial, public programs, and residencies team at Videobrasil, a cultural association dedicated to mapping and promoting art from the geopolitical South, having worked on two editions of the SESC_Videobrasil International Festival (now the SESC_Videobrasil Biennial).

More recently, she worked at Whitechapel Gallery in London, where she coordinated the Neon Curatorial Exchange residency program between London and Athens, and collaborated on a series of projects across Europe, in institutions such as the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco and PAC – Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan. An architect and urban planner by training, in Spain she has independently curated projects in institutions such as La Casa Encendida and the Sala de Arte Joven of the Community of Madrid, with a special emphasis on establishing spaces for dialogue and co-creation with the local scene, through transversal, collective, and collaborative proposals. She is currently preparing a solo exhibition of the Brazilian artist Regina Silveira for La Virreina Centre de l’Imatge in Barcelona (2024) and another curatorial project for the Centre del Carme de Cultura Contemporània in Valencia (2025).

Hero Image: Carolina Cordeiro, Retirar tudo o que disse, 2023. Zinc discs, variable dimensions. Courtesy: Galatea Gallery.