My studio is located in a central neighborhood of Athens called Agios Eleftherios, which literally means Saint Freedom. It’s not a trendy or popular area, but I find it deeply beautiful. Both of my parents grew up other, and I come from a family with roots in construction. In a sense, I’m the third generation of builders in my family, though my constructions are smaller and more intimate. I often reflect on how our past shapes our future—and whether we can fully grasp that in the present. Take bricks, for example. So many types and sizes, all originating from mud, dirt, and earth. Since ancient times, we’ve used mud as clay to build our surroundings. I see the brick as a more functional evolution of the same timeless approach to creation.

Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou. Courtesy of the artist.

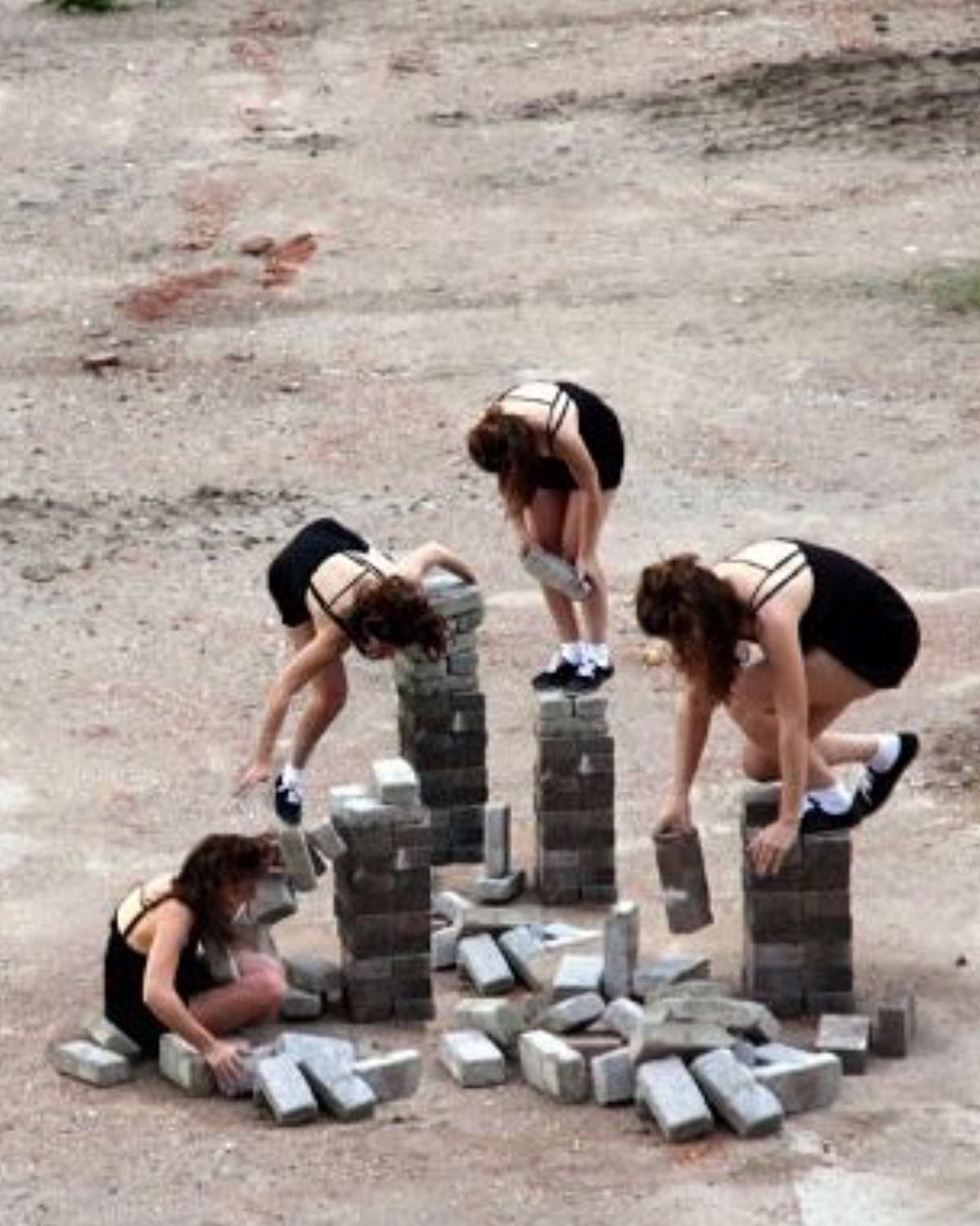

I’m so fascinated by bricks that I’ve dedicated an entire performance to them. “Sijmen Says” is a piece where I build a pedestal for myself while trying to balance on it. With each brick added, the pedestal grows taller, making it increasingly difficult for me to reach the next brick. The performance is marked by intense concentration and sweat, as if part of a precise yet inevitable ritual. Step by step, the bricks are stacked into a pile, creating a “pedestal” beneath my feet. It’s about growth, construction, laying foundations, and climbing—all with the goal of staying on top. Yet, despite my constant efforts to maintain balance, the outcome is inevitable: the fall.

As the pedestal rises, my body—thin arms and legs—becomes increasingly strained, pushed to the brink. I continue to climb, fearlessly adjusting my stance, determined to complete the task, even as the challenge becomes insurmountable. In this, I demonstrate a level of awareness and maturity, especially in the demanding and treacherous world of performance art. I don’t give up, even when the task becomes impossible, knowing that the collapse is imminent and inevitable.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

But it’s the fall that liberates the entire effort, unraveling the absurdity of the struggle, releasing me from the weight of expectations and limitations. Like body language, materials communicate with us in their own way. A broken pedestal, a pile of bricks, a ruin—each becomes its own installation. In my practice, every sculptural element holds deep symbolic meaning, laden with associations we cannot escape. An iron rebar is the skeleton of a concrete structure, while concrete transforms from dust into stone.

Recently, I stumbled upon a childhood notebook where I had written, “I want to become a chemist, so I can create chemical stuff.” Looking back, I realize this was my younger self flirting with experimentation—a declaration of curiosity that continues to drive me today.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

As a sculptor, it’s impossible not to reflect on the symbolism of materiality. Concrete surrounds us—cities, construction, development—it’s a man-made environment, yet intrinsically connected to nature. Sometimes, materials need a nudge, a movement, a heartbeat. My works are often activated through performance, transforming my sculptures into functional non-functional objects. In my performances, the core idea is rooted in human action. The presence of the artist creates a vivid, interactive dialogue with the audience. Physical communication naturally fosters a shared understanding, and for me, performance is the ideal medium to convey my ideas.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

In many of my performative works, I treat the body as a tool with limited capabilities—fragile and uncontrollably repetitive. For instance, in my recent solo show at the Theocharakis Foundation, located in the historic center of Athens, I created an installation titled “Ways to Lose Energy.” Large panels covered in gold leaf adorned the balcony of the fifth floor, a space once occupied by a bank, now overlooking the Greek Parliament. The installation featured an industrial arrangement of photovoltaic cells, creating an oxymoronic condition—non-utilitarian—as it mostly reflected sunlight, gradually losing its value through material decay. The wind wrinkled the gold, causing it to tear and scatter in flakes across the city.

On the second floor, viewers encountered “No_Body,” a performance in which two dancers engaged in a childlike game, manipulating gold leaf with their breath, attempting to keep it afloat. This paradoxical, futile effort—keeping “something” suspended—commented on the ephemeral nature of power and financial value. The repetitive blowing wrinkled the gold leaf, eventually tearing it apart, symbolizing the simultaneous decay of both material and human life.

Photo: Eftichia Vlachou. Courtesy of the artist.

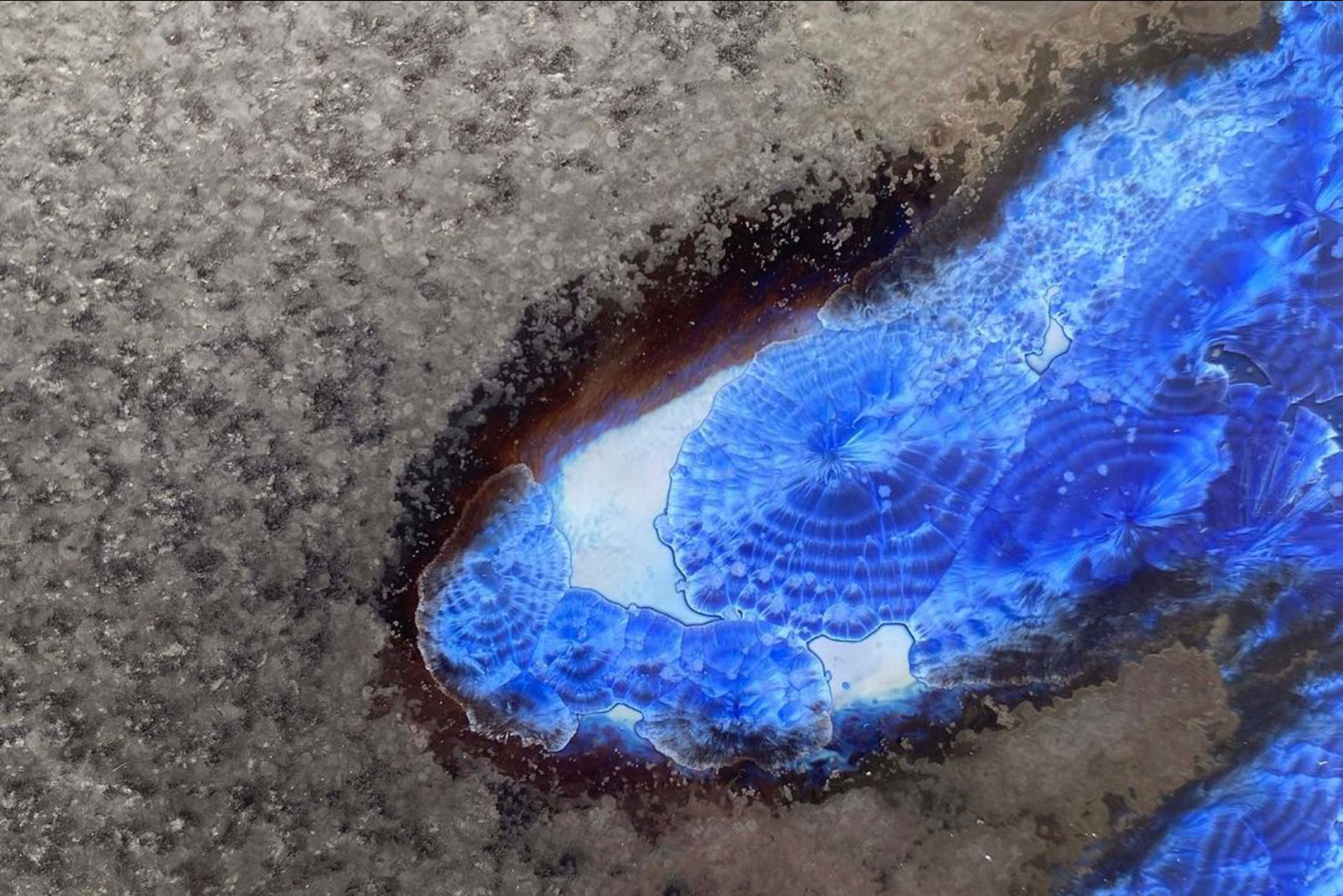

I’m fascinated by how the frenetic pace of industry exploits and misuses nature. Since industry is human-made, and humans are part of nature, are we not living in an era of artificial nature? Climate catastrophe is like weather: everywhere and always, the lifeworld made sensible. In 2023, I created a work that explored themes of beauty, destruction, life, and death, presenting the seen and unseen natural and artificial forces that drive human actions and have led to the climate crisis. In the Anthropocene era—where humans have become geological agents, altering the Earth’s processes—climate change, late capitalism, pandemics, and rapid urbanization have inflicted unprecedented disasters and deep grief over the loss of natural environments and human lives.

In “The Day Before the Western Wind,” I presented a body of work focused on environmental degradation and human intervention, framed within a post-apocalyptic landscape. This piece featured a floral scene made of black clay, combined with found materials collected after the 2018 Mati fire, the deadliest urban fire in modern Greek history. I transformed burnt car parts into a forest that emerged or decayed from fabric laid across the floor. The installation, exposed to UV light, caused the surfaces of photosensitive-treated fabrics to change, centering the artistic process within the exhibition itself. By exposing visitors to the harm of UV light, I brought the environmental threat to the forefront, making the experience both artistic and visceral.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Through these sculptural gestures, I aim to re-examine the consequences of human activity. I construct a world of earth and ashes that commemorates nature, inviting viewers to contemplate our future.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

I hope my work poses new questions about the nature of our essential relationships—both with each other and with the environments we inhabit, whether man-made or natural. With each new challenge, I strive to expand my intellectual understanding and empathy. I’ve always viewed my practice as a collective experience, not a solo endeavor. That’s why I collaborate with others, whether performers, dancers, scientists, or even Olympic athletes. Engaging with people from diverse backgrounds pushes my work in unexpected directions and provides a fresh perspective. One of the most exciting aspects of art is its inclusivity—there are no barriers to participation. Art can serve as a cultural melting pot, a fertile ground for exchange and dialogue on contemporary issues. It is the only true way to exist: through people who confront similar dilemmas, challenges, and ethical questions.

Photo: Giorgos Athanasiou. Courtesy of the artist.

You can find out more about Despina at @despina_charitonidi // despinacharitonidi.com/

Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou. Courtesy of the artist.

Despina Charitonidi’s work has been presented among others; Theocharakis Foundation, Greece, (2023), Atopos CVC, Athens (2023); Eins Gallery, Cyprus (2023); Microclima Festival, Venice – Cinema Galleggiante, IT (2022); 2022 Changwon Sculpture Biennale, South Korea (2022); Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, Novi Saad for the Serbian Pavilion Venice Biennale (2022); Callirrhoë, Athens (2021); Alkinois Project Space, Athens (2021); Ύλη(Matter)Hyle, Athens (2021); “Gemeinsamkeit und Kollektivität trotz Distanz”, Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik, Berlin (2021); Hydra School Projects, Hydra, Greece (2020); 2023 Eleusis – European Capital of Culture, Greece (2018); Utrecht Centraal Museum at Hoog Catharijne, Netherlands (2015); and MACRO,Rome Museum of Contemporary Art, Rome (2013). In the summer of 2023 she presented “Bodies floating into the land” under the context of All of Greece One Culture, at the Temple of Poseidon in Tinos island, with the support of the Greek National Opera and Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.