Miranda Hine, Making Beds Solo Exhibition at MARS Gallery. Photo: Simon Strong. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

Meg Slater: Do you want me to ask the first question?

Miranda Hine: Go on.

MS: Can you remember how we met?

MH: I can’t remember – I hope you don’t have a clear memory of it! (laughs)

MS: I don’t, that’s why I’m asking you! (laughs)

MH: We have always stayed connected through art, and that’s really what led to us starting In Residence with Sarah (Thomson) and Isabel (Hood). Were we both still studying at university when we started In Residence?

MS: Yes, we were. I remember I’d returned from studying overseas and received some advice from a friend to consider starting an ARI. I remember her describing ARIs as providing fertile ground for testing things out. What appealed to me was the consistency setting up an ARI would provide. At that time in my life, I didn’t feel particularly grounded. I was working across a lot of different paid jobs so that I could do unpaid internships at art galleries. In those internships I was never there long enough to get a good sense of how things worked or how decisions were made. So, starting an ARI provided an outlet that we otherwise couldn’t really access as university students.

MH: I agree. I was doing a lot of unpaid work, and while some of it was useful, you couldn’t really control what you were learning. I had one that was just scanning back catalogues. Good for the CV, but I wasn’t getting anything out of it. But beyond the shortcomings of some of these volunteer experiences, I think In Residence also came from our recognition that we had a peer group of artists who were making amazing work, and we felt they weren’t being shown enough or written about enough. We wanted to provide platforms for ourselves, but we wanted to do that for the artists we worked with as well.

MS: I remember there were a fair few ARI’s that had started putting up shows in their homes and their backyards. The Laundry and Cut Thumb come to mind. It felt like everyone simultaneously came together in appreciation of the format and the agency it provided.

MH: It was an interesting way to collaborate. You, me, Sarah and Isabel all had quite defined roles in our ARI, but we also crossed over fair a bit as well. It was a flexible model that could change depending on what we wanted to get out of each project.

Learning about the history of the ARI in Queensland was also really rewarding. The ‘do it yourself’ attitude of the ARI presenting exhibitions in non-commercial spaces has a long history in Queensland, predominantly out of necessity due to a lack of government funding.

Home 2 exhibition – Publication cover designed by Isabel Hood.

MS: Shifting the focus a bit here, but when did you first develop an interest in making art? Can you remember? For as long as I’ve known you, you’ve always balanced your interests in learning about art and making art.

MH: I can’t identify a starting point. It was just mum being an artist and always having a studio in the house. There was always a room that was hers and filled with every piece of art equipment you could imagine. She also ran after school art classes with her friend Britt called ‘crunchy art’.

MS: That’s a great word – crunchy.

MH: Yes! And my sisters and I would always go to those after school classes. Mum also took us to lots of art galleries growing up, and sometimes the work of her and her friends was on display.

MS: So, it was all around you.

MH: Exactly. And she would always talk about art and be very patient in explaining something so that we understood it. So, for us, it was just another way of seeing the world. There was never any separation between art making and any other form of expression.

How about you?

MS: My dad used to paint a lot. I remember going on family holidays to the beach, and he would leave for hours at a time to paint the water, the boats and the birds. It was a very private activity for him, and he never really spoke about it. My only exposure to what he was doing was when he would bring his canvas back at the end of a session, and it seemed as if it had been magically transformed. Your mum brought you all into her art and it became a part of your worldview. For me, art was for the person.

MH: That’s so interesting. It must’ve been a strange experience, seeing the product and not knowing how your dad got there. For me, it was always about the process.

MS: Your art practice and your curatorial practice, to me, have always been intertwined. The issues you consider as an artist and the issues you consider as a curator, from what I can recall, have always overlapped. Hearing about how much you were exposed to art as a child – this makes perfect sense. It’s natural for you to bring these things – which for some people are distinctly separate – together.

MH: Exactly. I struggle to articulate this, because to me it’s obvious, but I realize it may not be obvious to everyone. My art making and my curating are interlinked. They explore the same ideas, just through different formats. To me, writing an essay is the same as creating a body of work. Both are communicating something and processing my ideas for other people to access.

MS: Beyond these formative experiences, how did you develop such a close relationship between your artistic practice and curatorial practice?

MH: When I was doing my undergraduate degree in sculpture, I was exploring the functions of museums, and how we use museums as authoritative forms of storytelling. I was making work that was sort of recreating museums and trying to construct narratives that people would believe or question, even if they were fictional. After graduating, I stopped making work, because I thought I needed to know more about how we build stories in museums, so I began to do curatorial work in museums. After a while, I returned to my practice. This was purely in response to a physical need to make work again while I was writing my masters dissertation. And it’s only really in this past year that I’ve finally got to a point where my curating and artistic practice exist together.

MS: Is that the first time that’s happened? That they’ve co-existed?

MH: I think they have been intertwined before now, but it hasn’t been until the past year that they’ve both dealt explicitly with the subject of the museum.

Left Image: Miranda Hine, Dennis Severs’ House (window nook), 2023. Oil on board, 16 x 12 inches. Right Image: Miranda Hine, Dyrham Park House (larder), 2024. Oil on board, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

MS: This might be a bit tangential, but I have a similar experience I thought I’d share. When I was writing my master’s thesis, I was also working on the NGV’s QUEER exhibition. For a long time, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write my thesis about. Eventually, I found a text by two museum educators (Jennifer Wild Czajkowski and Shiralee Hudson Hill, ‘Transformation and Interpretation: What is the Museum Educator’s Role?’, 2008) about the importance of working at the margins of an institution, rather than at its centre. Drawing on bell hooks’ writing on the margins as a source of power, these educators highlight the margins as a place of power, and the best position from which to work with marginalized communities. It was from this point that I decided to explore the question: what might a marginal curatorial approach look like?

Everything I was writing about fed directly into my curatorial work. It was a very special experience. Within the QUEER curatorial team, I ended up being the curator who worked most with various community groups we collaborated with throughout the exhibition. This collaboration usually took the form of public programs – a format that is a real interest of mine. By working directly with queer community to build public programs that provided different points of entry into QUEER, I was trying to shift myself outside of the institution’s centre, and these experiences influenced how I approached my thesis.

MH: QUEER was incredible work. This makes me think about how lucky we’ve both been to wait to do our master’s degrees until we are sure of what we are interested in. It’s allowed us both to fully integrate it into the work we want to be doing.

I have another question for you. I know that you were exposed to art through your dad, but I’m always so impressed by people who make the decision to enter the art world. I feel like I entered it accidentally through the doors my mum opened. How did you make the decision to enter the art world, and why didn’t you go down the art making route?

MS: Believe it or not, my answer is linked to your mum.

MH: Oh my god.

MS: Well, you know she was my high school art teacher.

MH: Yes.

MS: She paid close attention to each student’s interests and strengths. I remember I would make artworks, and I wouldn’t really get anything from it. But what I did love were the A4 and A3 research journals we prepared to support the artworks we made. I remember wishing that the journals could be the central focus for me. I really loved mapping out my research and learnings. Towards the end of high school, we started to write essays about different art movements and artists. I’d mentioned how much I’d liked the process of writing an essay much more than making an artwork, and I remember your mum suggesting that studying art history might be a good fit for me.

MH: I feel like you’ve always had a very clear sense of direction, professionally speaking. I’m curious to know when you made the decision to pursue curating, and whether it was straight forward for you.

MS: It’s funny you say that, because for a long time I felt like I was following directions from other people. During my first lecture at university, my lecturer told everyone to go and get practical experience, so I went and volunteered in the Exhibitions Management department at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art. After interning there for a while, I wanted to understand how other departments worked, and how different sized institutions worked, so I started interning at other galleries around Australia, and eventually sought out some international placements. So, I suppose I did have conviction, but I was constantly doubting myself. I think this was the product of doing unpaid work for such a long time. I often wondered if the quality of my work was good enough for me to be paid. Until relatively recently, I hadn’t realized how formative my start in Exhibitions Management was (rather than say, curatorial, which I eventually moved into). Exhibitions Management gives you a global view of the very complex structures and systems involved in presenting exhibitions. I was interested in curating as well, but I didn’t want to work in a vacuum. I wanted to understand the logistical and financial factors that influence exhibitions, rather than just thinking curatorial. My current role at the NGV allows me to do this.

MH: That is my favorite part of curatorial work. I love working closely with other departments and being the person who is across the ripple effect of how things need to fit together to make something happen.

MS: That’s such a great way to put it – the ripple effect. Ultimately, it is all of the curator’s concern. Exhibition budgets, marketing materials, publication proofs – these are all central parts of building an exhibition.

MH: In my current role at the Natural History Museum in London, there’s a much more traditional curatorial structure. The curators are scientists with very particular areas of specialization. Me and my team are responsible for interpreting their research and ideas to make exhibitions. We interpret the knowledge, rather than being the knowledge holders. I much prefer being in that position, although it still comes with a heck of a lot of responsibility.

MS: Sometimes I feel like the structures and systems upheld within historical museums and galleries can make self-reflection difficult. Take the language used in labels and other interpretive materials, for example. In large cultural institutions, there is a preference to use definitive language when discussing artworks and other cultural materials because we, as the ‘knowledge holders’, are meant to have the answers. But this is impossible when we are dealing with lesser-known histories, which either weren’t adequately recorded, or weren’t recorded at all. When I was researching for my thesis, I became really interested in the emergent curatorial practice of embracing non-definitive language – the ifs, the buts, the maybes.

MH: There is a real hesitance to embrace ambiguity, but people’s lives are ambiguous, and to try to translate that into something definitive is not truthful. I enjoy writing labels that are just questions. On that, I think it’s important to embrace less academic approaches to writing.

MS: I find the hardest texts to write are labels for children. You must distill often extremely complex ideas down into around 50 words using very clear language. These kinds of texts offer such an important learning experience in accessible writing. Do you feel that your studies in fine art had more of an openness to how you can think and write about art?

MH: Yes. While I missed out on some of the more rigorous research and writing that you undertake in an Art History degree, I was given more flexibility in how I learned to write about art. This makes me think about the importance of getting and giving feedback on your writing, which is something I’ve really grown into with time. I used to be quite controlling in how I would give feedback on a person’s writing. I wouldn’t see it as someone else’s text, and would think, “well, that’s not how I’d write that, so you need to change it”. I’ve learned to leave space for how other people want to say something. But commissioning writers to write about my art practice has been a learning curve!

MS: Oh, that must be so weird – reading someone else’s impressions of your work.

MH: I’ve written reviews for other artists using my own voice, I’ve written texts as an exhibition curator, but having people write about my art practice with their voice is a totally new experience for me. It’s where I’ve found out that I am more of a control freak than I thought I was! I have a strong desire to control how my work is spoken about, but I am also very interested in challenging the narratives that often dictate how we learn about artists and their works. So, that’s a real tension, for me. I’m lucky to have worked with some brilliant writers who bring a whole new perspective on my practice every time.

MS: I think both things can exist at the same time – the desire to control the narrative and the desire to break it down and call it into question.

I have another question for you. Well, two actually – but they are related. First, why do you paint from photographs? Second, can you describe how you make an artwork, from start to finish?

MH: I have painted from life, and I do enjoy it, but there are practical limitations to it. You must be set up in a space to paint from life, and this is difficult for me, given my interest in historical museums. Even if I did get permission to paint in these places, I wouldn’t be comfortable, and the work wouldn’t be good. I take photographs quite quickly and badly, which can result in my subject being blurred and difficult to read. But I like this. I lean into the ambiguity of my photographs. I like to build up forms that are both figurative and abstract in my paintings. I also really like the framing and compositional devices of a photograph.I just use my phone to take my photos. That’s why my storage is always full, because I’ve got so many stupid photos on there. (laughs)

MH: Sorry, I don’t think I answered the second part of your question.

MS: How do you make a painting, from start to finish?

MH: I always think in series. I might go somewhere and take photos that appeal to me, and then connect them with similar photos I’ve taken elsewhere. Other times I’m much more intentional about it. I’ll go to a specific place to take photos with a series in mind. And sometimes I’ll sit down in my studio and look back through my camera roll and make an album of photos that are linked visually or conceptually, and that will form the starting point of a series. It’s rare that I’ll make a work that can stand on its own. I feel it’s richer to have the context of a series, because each work is doing something different within the series. From a practical standpoint, I’m never sure of how I’ll paint something. I’ll have an idea of how I could translate an image into a painting, but the actual process I take is always different. I don’t have a set plan. If I did, I’d get bored of it quickly.

MS: Is there any other medium you’ve thought you might like to try?

MH: The physicality of painting is still holding interest from me. But coming from an interdisciplinary background, I always found more value in that, in terms of translating an idea, because it can remove the ‘that’s a pretty picture’ response that can prevent deeper engagement with paintings. I could see myself working in installation again, but I’m not feeling like I need to do that yet. I’ve always been interested in the idea of people physically responding to what I make, but I have’t integrated this into my work at all yet. I like the idea of an audience being able to move works around and put them in an order that makes sense for them.

MS: This reminds me a bit of a work by Faye Toogood (Downtime: Daylight, Candlelight, Moonlight, 2020), which was presented as a part of the second Triennial at the NGV. She painted all over the walls of one of the NGV’s 17 th century Flemish, Dutch and British collection galleries, and her sculptures were interspersed with NGV sculptures. She placed her work in dialogue with NGV collection works. It makes me think of your practice and where you might like to take it.

MH: I love that idea. The dream is working with museums and galleries to create works that respond to the stories they tell through their collections.

Miranda Hine in her studio. Photo: Dimitri Djuric.

Miranda Hine, installation view Making Beds Solo Exhibition at MARS Gallery. Photo: Simon Strong. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

MS: To end where we started, is there anything from our time doing In Residence that you have carried into what you do now?

MH: Being able to do a bit of everything, and not thinking I can only have one, particular set of skills. I think what we did together gave me the confidence to know I can learn to do a range of different tasks to bring an exhibition or project together. Install, editing, collection work and so on. Even though we were working on a small scale, with little or no funding, it was still very valuable. In fact, maybe even more valuable because we were doing everything ourselves. What about you?

MS: I agree with everything you said. Also, In Residence gave me a sense of belonging in Brisbane’s art scene. There was a real sense of community and solidarity amongst the network of artist and curator run initiatives in Brisbane. We all went to each other’s shows, and through that process met so many artists and arts workers. And this paired with our online presence – our interviews, reviews and Instagram takeovers – connected us with our community.

MH: That’s really special.

Left Image: Miranda Hine, Leighton House (studio), 2023. Oil on board, 7 x 5 inches. Right Image: Miranda Hine, Dennis Severs’ House (plate stack), 2024. Oil on board, 14 x 11 inches. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

Miranda Hine, Dennis Severs’ House (bed), 2023. Oil on board, 9 x 6 inches. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

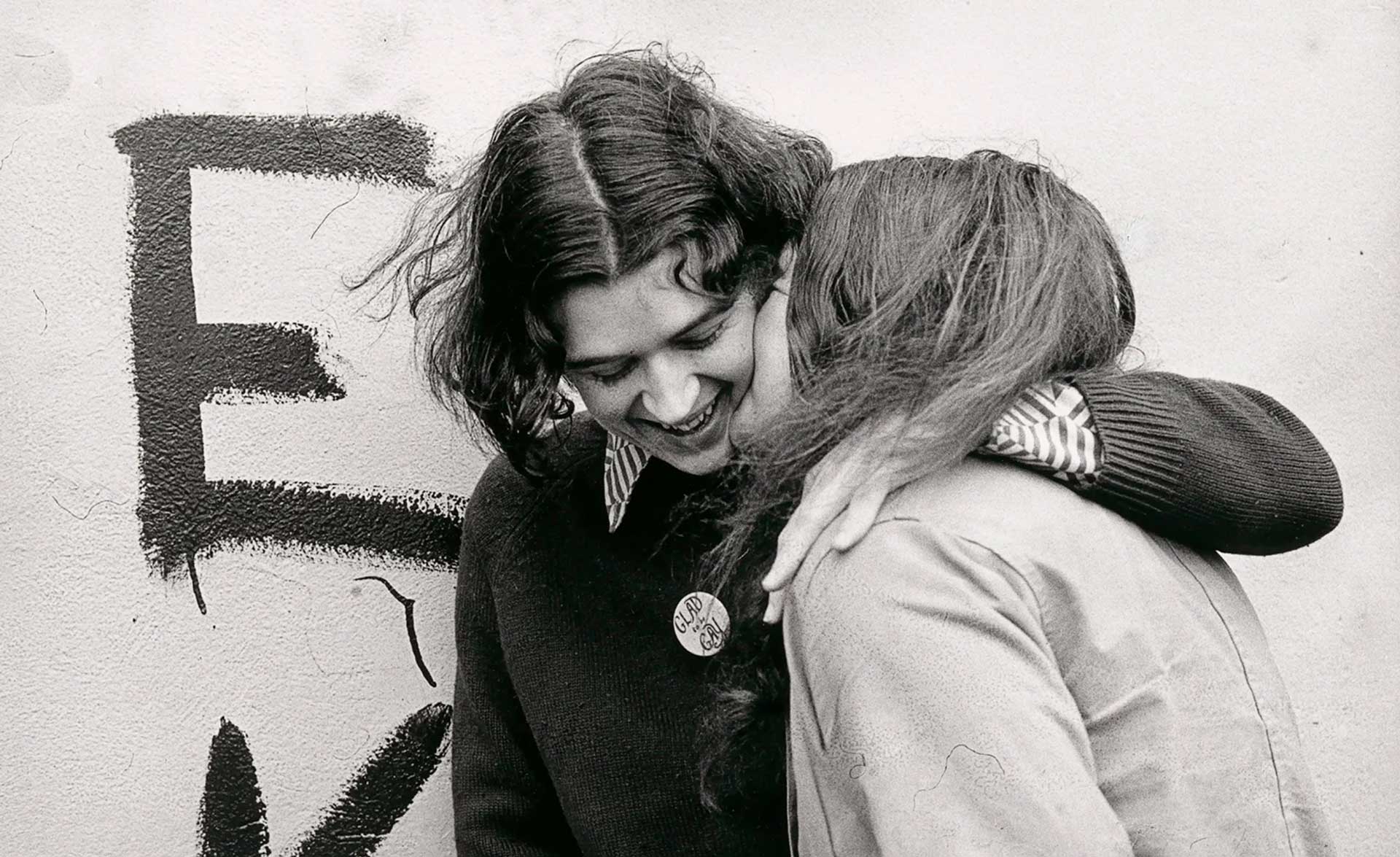

Meg and Miranda first met in high school and became fast friends through their love of art and writing. While studying at university (and joined by their friends and peers, Sarah Thomson and Isabel Hood) they formed In Residence, an artist run initiative (ARI) that operated in Brisbane between 2015 and 2018. In Residence presented four exhibitions in domestic settings and printed publications focusing on local emerging arts inBrisbane. The ARI also had an active website (which unfortunately no longer exists), on-which its founders would often post artist interviews, reviews and catalogue essays. Using Instagram, In Residence regularly invited Brisbane artists, designers, writers, curators and other creatives to host an account ‘take-over’, through which the account’s followers could deep dive into different corners of Brisbane’s diverse art world.

Despite the ARI’s end and conversations now being few and far between, Meg and Miranda remain connected through what first brought them together. Although now, after each spending close to a decade working in art galleries and museums around the world, a shared interest in art has transformed into a strong desire to see change in how art histories are recorded and told within these institutions.