When I arrived in New York at the end of April, I quickly felt the need to create a kind of “home” around me, through my habits, objects, and the small choices I made. After spending over two years learning to be a father—my first child was born in 2022 and is now 2 years old—I found myself alone, far from home, and completely immersed in my work. Being away from my family, from the home we nest in, and from the daily routine was incredibly challenging from the start. Because of this, I felt the desire to gradually build, in my new studio, in my work, and even within myself, a slower, more personal time, an atmosphere of calm and concentration, a setting conducive to processing this experience of solitude, distance, and novelty.

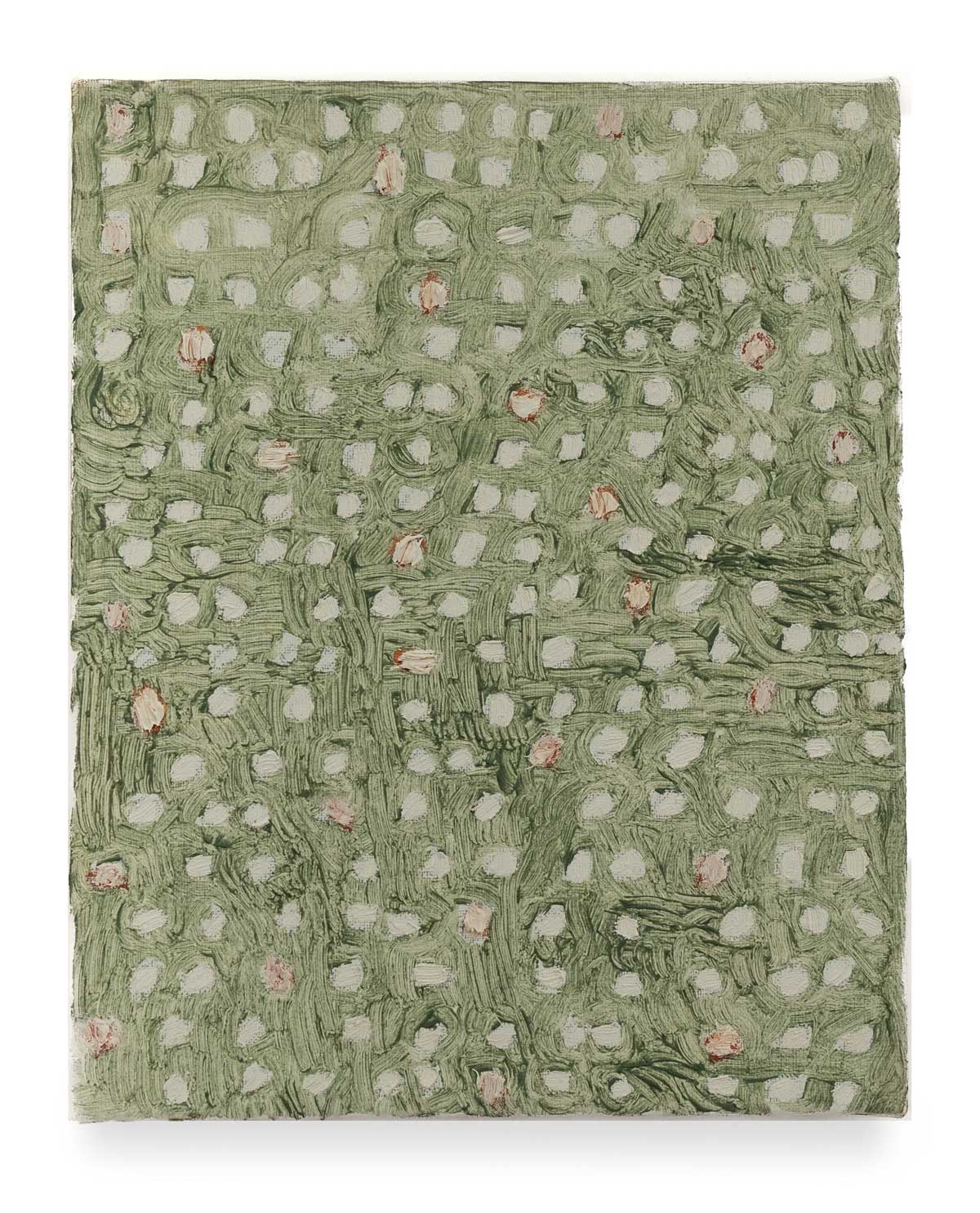

In the paintings, this manifested through layers and layers of paint, scrapings, and pentimenti; countless hours of painting, driven by a desire to evoke a strange yet comforting light, crafted with a touch of affection and oddness. I wanted people to connect with the paintings on an emotional level, for the paintings to offer a sense of calm, flavor, and silence.

Along with the new subjects that emerged during the residency, I also discovered other ways of constructing the surface, deepening my long-held desires to experiment, research, and take risks. These organic shapes that resemble fruits—circular, oval, and slightly irregular—had already started appearing in my work in São Paulo, but in New York, I became increasingly interested in their relationship with the small “dots”—tiny marks that appear in almost all the pieces and that I’ve sometimes referred to as “seeds.” This relationship began to point me toward ideas of fertility, planting, and living systems.

From a very young age, I was constantly walking along trails and exploring caves in the Southwest region of Brazil with my mother, deep in the Atlantic Forest. She, a public agent and environmental conservation advocate, worked at a state park managed by the Forest Foundation of São Paulo State, where many kilometers of native forest are preserved (Intervales State Park, Ribeirão Grande – SP). My family and I were always there. Although my mother no longer works at the park, we still visit occasionally to this day.

My father, a veterinarian, also introduced me to animals from an early age—dogs, cats, their various breeds, their playfulness, surgeries, and anatomy. I spent a lot of time in his clinic, observing his care for the animals and their owners. The relationship with nature—fauna, flora, behavior, culture—has always been a subject of direct experience for me. I believe this deeply influenced me, in a way that is both spiritual and aesthetic. I hold a deep reverence for these memories and am convinced that our natural environment is a sanctuary and a significant source of the poetic elements I strive to infuse into my work. Even so, it’s always been—and still is—challenging for me to connect my artistic practice with the deep desire to explore and immerse myself in this theme. I want my work to also embody displacement, curiosity, doubt, vulnerability, nonsense, and illogic.

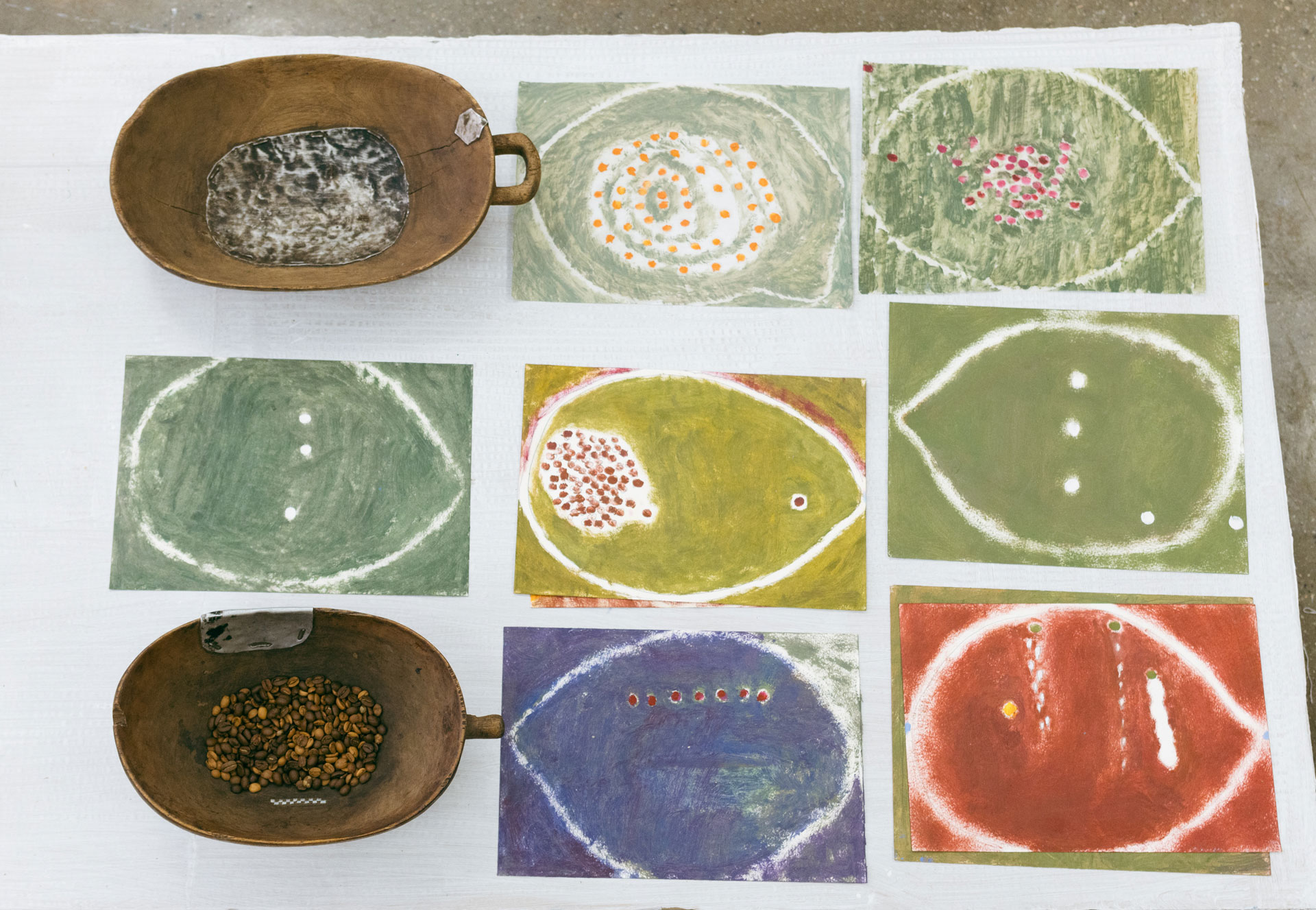

I started this practice after returning from a búzios reading and realizing that there is a relationship between chance and precision in oracular games: a stone or shell cast by chance provides more or less precise answers, suggests a way of seeing, reveals something previously unseen. From this exploration, more rounded forms began to emerge, echoing the table where búzios are cast—a space that concentrates a process, a closed circular body that also resembled microscopic images of cells, stellar bodies, as well as fruits, seeds, and leaves.

In New York, I created a few pieces using this “method” of throwing seeds, but the oval shapes that resembled fruits were directly related to the theme of seeds and could still suggest more compositions and possibilities within the subjects and methods of creating. I completed some works that associated the positions of the marks—“seeds”—with musical rhythms and claves of instruments, such as the tamborim—a percussion instrument used in Samba. This allowed me to connect the practice of painting to my musical practice.

With the exception of a few pieces, most of my work features these marks, dots, and small gestures. I refer to them as seeds, but I also like to say that they tension the space, much like a body in a net, a sound in silence, or an accent in a word. I like to think of them as the seeds of a painting’s ecosystem, each with its own nature and natural laws. The layers of paint that create atmospheres are also part of this same nature, a soil for the seeds. In this way, they may allude to the “natural world,” but they possess autonomy and their own reality.

I have been represented by Galeria Estação since 2022, when I had my first solo exhibition titled Deni Lantz: Pinturas, curated and written by Ivo Mesquita. Even before being represented by the gallery, I frequented their exhibitions and admired the artists they represented, and all the work of Vilma Eid with Brazilian art. Her work is of immense importance in Brazil and the world. For me, it is very significant to be close to the works of artists like Véio, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, Neves Torres, José Antonio da Silva, among many others. For me, as a reference, they are of the same importance as established global North artists. Vilma’s work has been increasingly pointing in recent years toward bridging the gap between Brazilian “popular” art and contemporary Brazilian and international production.

During the residency, I reflected a lot on the relationship between my references and deeper cultural roots as a Brazilian and the experience of being in contact with New York City, its complex culture and reality, connecting with the gallery’s work and its purposes, and I understood the weight of our Brazilian production even more intensely. It was thanks to the constant support of Galeria Estação and its team that I was able to have this rich and transformative experience.

You can find out more about Deni at: @deni.lantz__ // galeriaestacao.com.br/en/artist/102/deni-lantz

Photos: Camilla Loreta