Ana Lira: I have a background that connects me with the foundation of the work you are developing. I was a civil engineering student for almost five years, and part of the processes that made me correlate with the course had to do with experiences and geological processes. I really liked the study of rocks, but that already came from my adolescence. The scientific activities I did during high school were connected to rock processes or dynamics of physics, astronomy, in short, the study of the universe as a whole. When I went to study civil engineering, these studies kept me in the course because it was very challenging to be there, being a Black woman and practically one of the few women in the entire university.

Valentina Tong: Did you study in Recife?

AL: Yes, I started at the University of Pernambuco, which, being state-owned, had a somewhat complicated articulation process. Many professors came from the traditional job market which added complexity to the academic environment. They seemed to prioritize the title of “professor” over the actual act of teaching, therefore I decided to transfer to the Federal University of Pernambuco. At this institution, I became involved in geological expeditions due to the excellent soil studies department available. I joined the excursions as a way to take independent courses, and that brought me closer to this process.

VT: Wow, that’s incredible.

AL: Recife is a city that, like New York and Amsterdam, is practically at sea level. It’s no coincidence that the Dutch, during colonial and exploratory voyages, chose Recife as their first port. And when the Dutch occupation in Brazil failed, they left Recife and went to the United States, occupying the island that became New York. I jokingly say that Manhattan wouldn’t exist if Recife didn’t exist. It’s a city that has a significant contribution to colonial structuring dynamics. Much pau-brasil (Brazilwood) and raw materials for the construction of these cities came from there, not only what returned to Europe but also what the Dutch took to the United States.

VT: How were the expeditions during your studies?

AL: I visited the Port of Suape, where I studied some of the sea occupation processes in Pernambuco. The entire Atlantic Forest region of northeastern Brazil, which was deforested, experienced, as a result, the process of silting. This created a profound impact on the soil, rock transformation, and land transformation. Erosion not only affects the rock process and soil dynamics but also the design of this geography. I think that having lived through this experience, I was able to see it very well in your work when you were going through your processes.

VT: The encounter during the residency expeditions proved to be quite interesting.

AL: The visit to Botucatu was more than just getting to know a geological area and an archaeological site. For me, it was an observation of how that place functions after the occupations, how all the dynamics you brought from the sedimentation of rocks over billions of years are flowing away in seconds, with the very abrupt intervention of a quarry, for example. So, observing that landscape was reflecting: “who could have reached there? How was it structuring itself, and how was it surviving”? There’s another type of intervention, which is the rocks being shaped by the wind. But it’s not as invasive, destructive, and short-term than the presence of a quarry for asphalt production. The visit was very symbolic in making me reflect on other notions of time, a geological time that we need to realize when we effectively use the results of transforming these rocks into raw materials for daily life. Thinking about your trajectory, what connects you to this type of element in Earth’s cosmology? How did you develop this relationship with rocks?

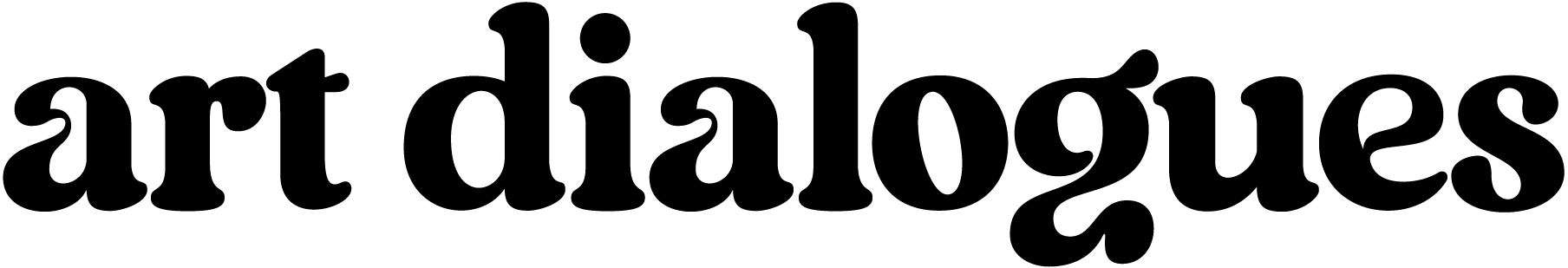

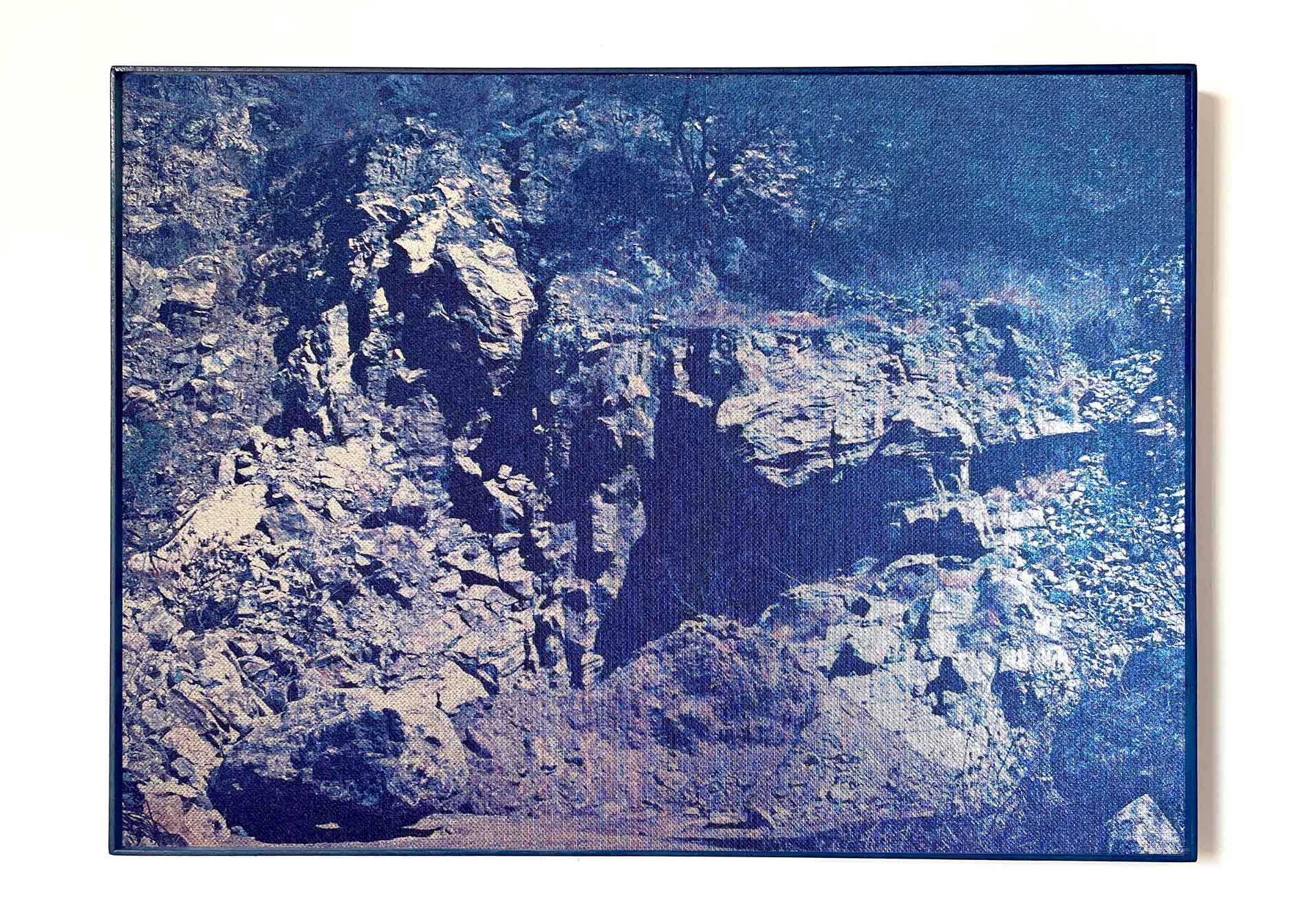

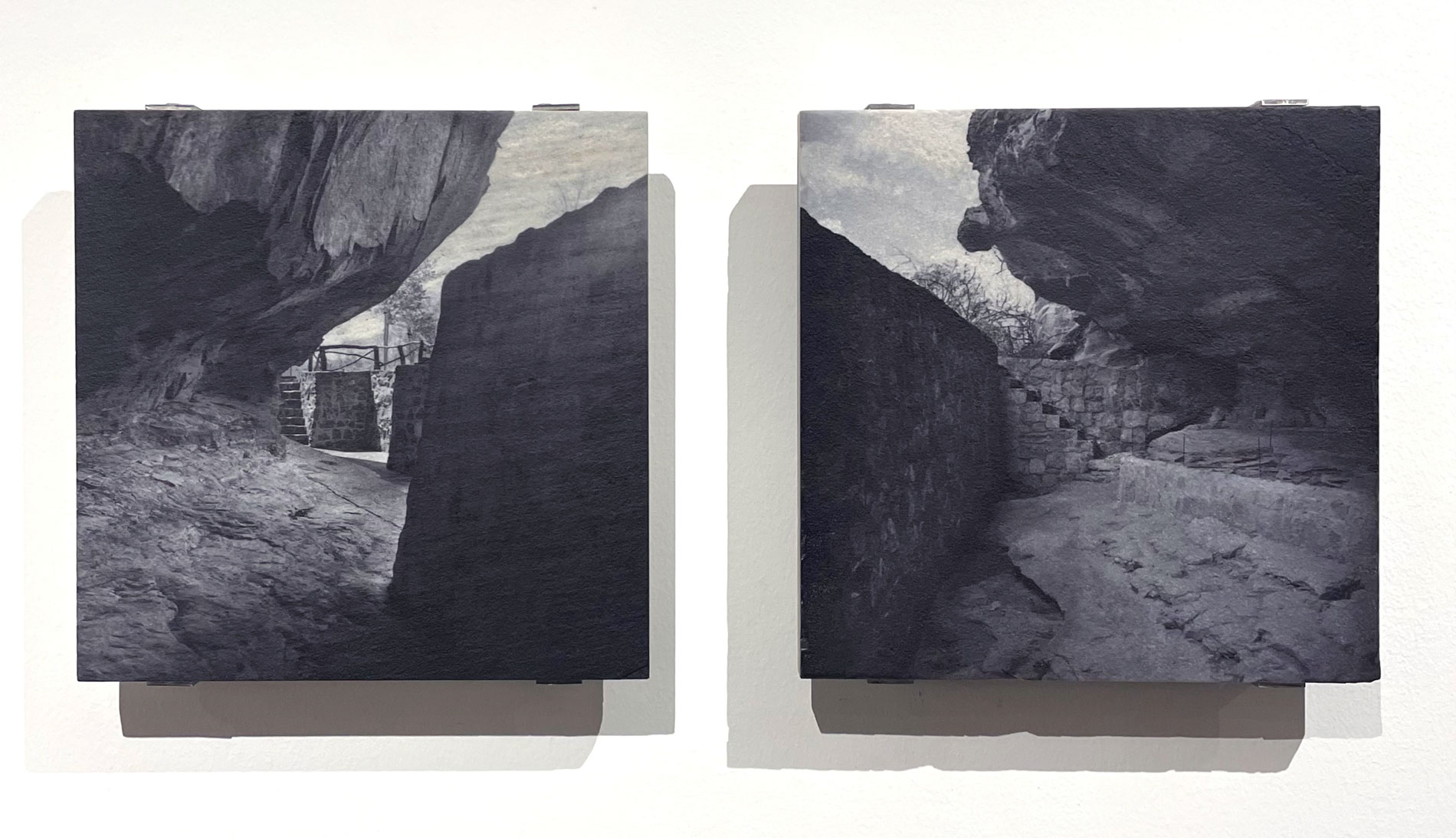

Valentina Tong, Basalto I e II (diptych), 2023, Pedra Paulista, 21.65 x 21.65 inches. UV printing on silver cedar fabric. Courtesy of the artist.

Image on the left: Institutional video of the basalt quarry explosion. Image on the right: Valentina Tong, Basalto III, 2023, Pedra Paulista, 21.65 x 21.65 inches.

UV printing on silver cedar fabric. Courtesy of the artist.

VT: I think it’s the materiality, the structure and the history of rocks that interest me. My background is in architecture, but during college we didn’t study where the materials came from. We know how cement and concrete are made, for example. We learn the function of each material, but we don’t go into the field to study how this material is extracted, how many years it has, and how long it took to form. Geology came through this, in the curiosity to understand the origin of the materials we use. When thinking about urbanization, we are not only deforesting forests and polluting rivers, but also suppressing geological material, which is the basis of the territory. We recently saw an entire neighborhood in Alagoas collapsing due to rock salt mining. I am interested in extraction and altered landscapes, but also in the “untouched” landscape, although they have already been greatly transformed by our occupation. Trying to portray, document, and go after these “original” landscapes, which still exists in Brazil, is very interesting. Through the image, it’s possible to imagine what that landscape might have been and how it could have existed and emerged. I am very amazed by the possibility that we today, can access such ancient materials that date back to the planet’s formation. Archaeology came to me in a second moment. While researching geological landscapes, I became interested in rock paintings and engravings. Rock shelters with traces of occupation indicate residence of the native peoples. I am interested in the relationship between geological structures and dwelling as well as paintings and engravings with the idea of representation. It’s a documentation of structures that are disappearing, a research that deals not only with the destruction and transformation of matter but also with the disappearance of representations.

AL: I wanted to discuss with you whether it makes sense for us to use the term “representation.” Since these processes are not static or sealed, they are not a mimesis or a direct symmetry between what was established hundreds or thousands of years ago and now. Because even these drawings or traces of the occupations of these populations are constantly shaped and constantly interfered with by the lives that came afterward, these lives are not necessarily human; some animals pass by those rocks, water, and plants that cover, then recover—also, the movement of the rocks themselves. The planet is in motion, even if we don’t perceive the internal movement, even if we don’t perceive it all the time.

VT: I find this thought interesting. It’s tough to comprehend the geological scale, the dimension of how old it is. It’s an exercise in grasping the different times of a landscape. For example, when we talk about archaeology, we think of a study of the past. We’re going to excavate something from the past, from ancient history. On the other hand, if this rock or this painting materializes here in front of me now, it is part of the present and, therefore, a continuous process of occupation. Confronting the geological scale, we create a proximity between a group that occupied the space at that moment and made certain drawings and me, who is there in front of that same place, photographing these records. I would say these are multiple representations.

AL: The term “representation,” for me, is complex. It may be a term I don’t like very much, but when you go into the field of exact sciences, for example, drawing a rock or a space from those scales of 1/25, 1/50 is also called representation. You are creating spatial relationships that allow you, at least hypothetically, to gauge the actual dimension of what is on paper. Photographic work doesn’t necessarily create scale relationships between what’s in the image and what’s outside the image. The photograph itself, the framing, already disturbs these relationships. At the same time, it brings a dynamic that is the possibility of narrating your perspective about what you are experiencing. Could you provide more insight into the observation strategies you’re currently using?

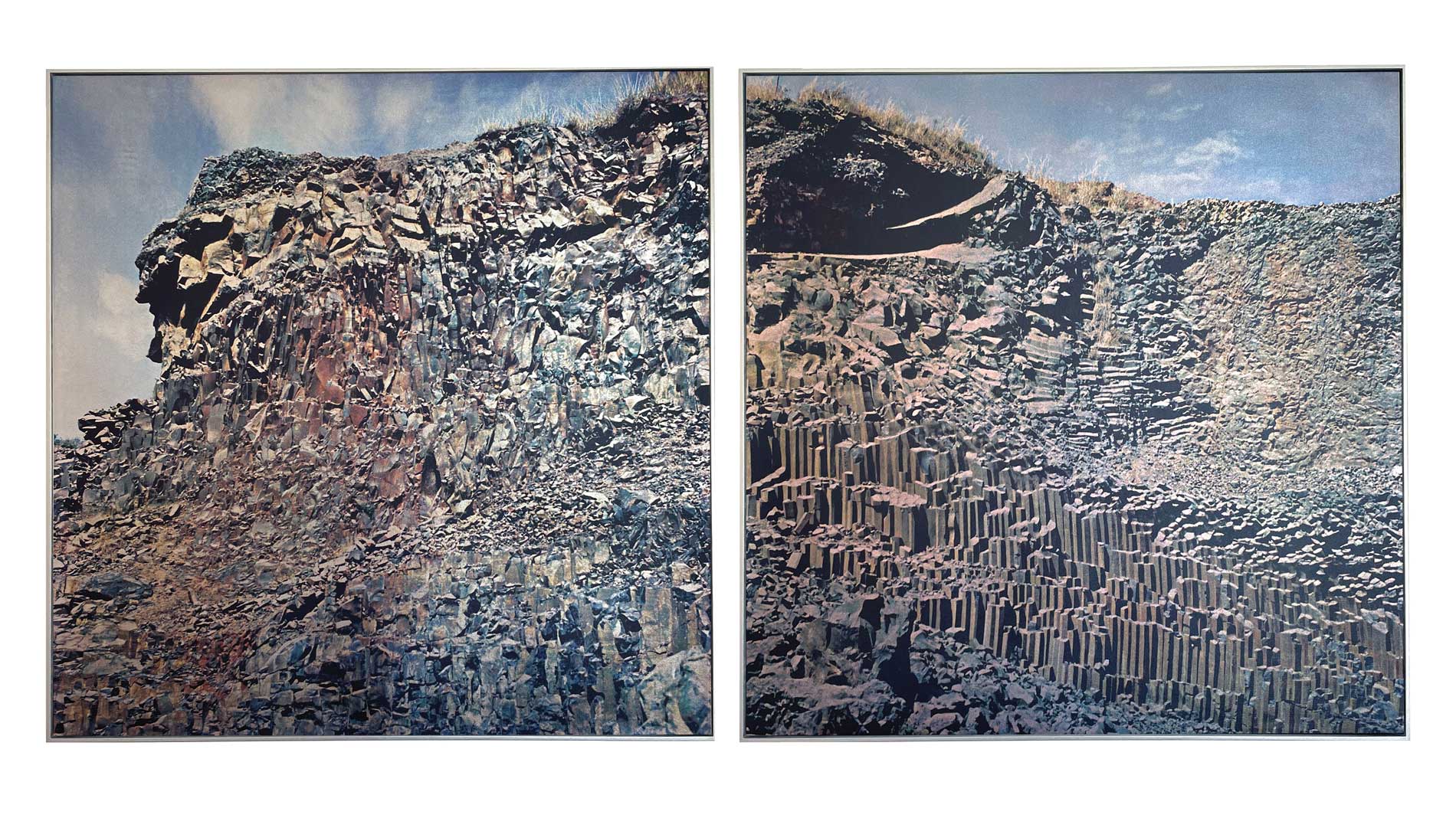

Valentina Tong, Seridó Potiguar, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

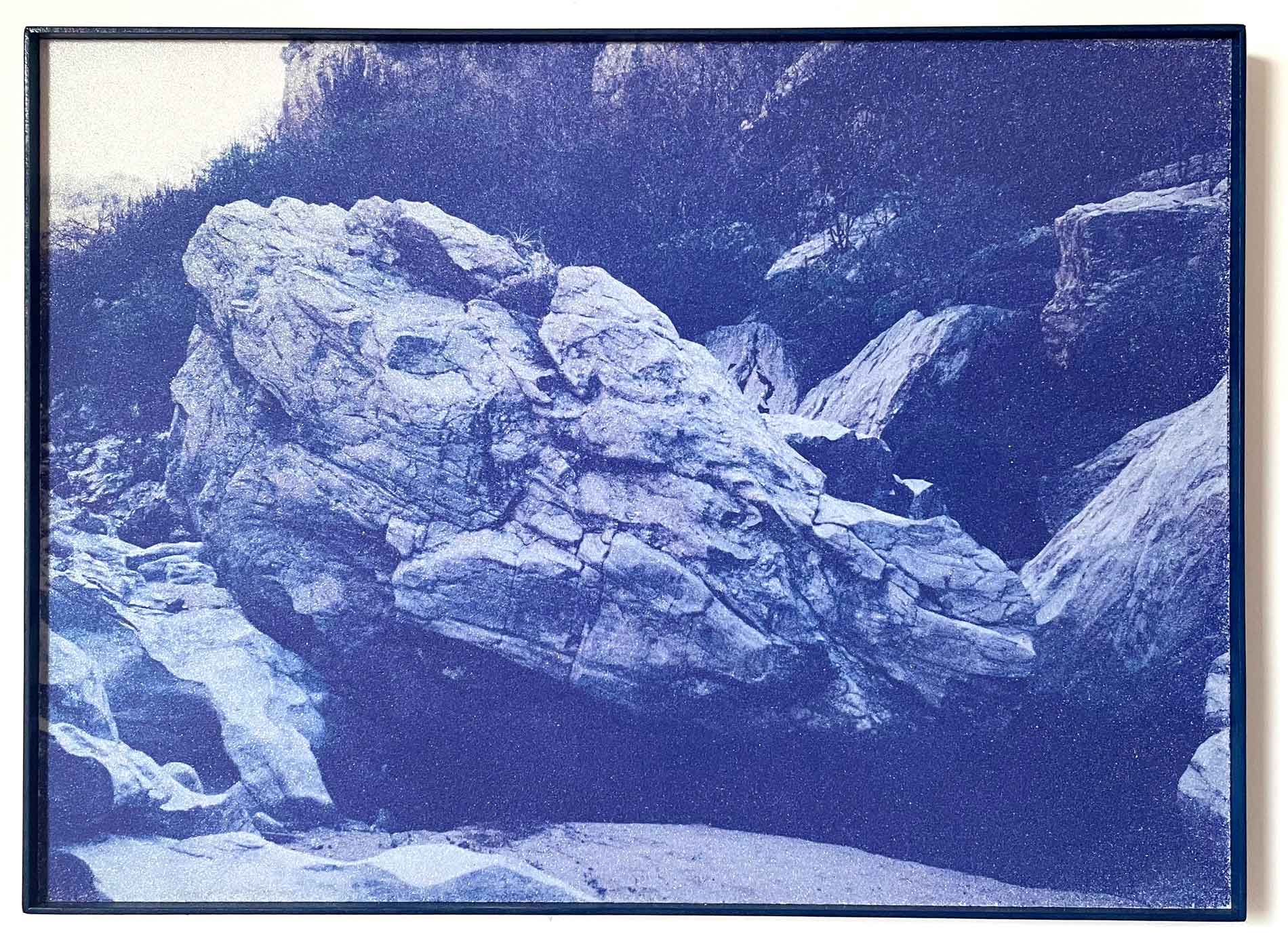

VT: In our expedition during Saúva, for example, it was essential to take the time to understand the geological context we were entering. It was valuable to have driven on dirt roads for almost forty minutes, crossing that impressive sugarcane monoculture along the Tietê River. We reached a small hill that survived erosion and occupation processes and that had millennia-old rock engravings. The state of São Paulo is not known for having rock engravings. This was a highly revealing aspect of the research, as well as exciting. I am from São Paulo and I have been researching archaeology and geology in Brazil, yet I hadn’t looked at my own state. When I started producing the Pedra Paulista project, I met Marília Perazzo, an archaeologist responsible for mapping and inventorying what still exists of rock engravings in São Paulo. Facing the scene, I’m not exactly looking for documentary photography, but perhaps more of a sensation, materiality, or construction of another landscape. The images have changes in colors and scale, and it’s even a provocation to archaeological photography that uses some kind of scale, some tool recorded alongside the rock painting, for example, to have a more precise, more scientific photograph. I’m interested in these deviations from the original landscape.

AL: When we were together doing the expedition during the residency, I didn’t photograph the space. Instead I did a lot of exercises observing the space and also observing what you were photographing. Taking a moment later to review the images you shared was truly beautiful for me. Discovering the direction of your gaze and the perspective you were exploring was enlightening. We are giving up, in a way, this geological heritage and sometimes, in such a random way because not everything produced in the construction industry is used. A lot is thrown away and what is discarded doesn’t turn back into rock, right? We are crushing, imploding, and exploding a heritage at a much faster rate than is effectively used in our daily lives.

VT: Why are there no more engravings and paintings in the state of São Paulo? Most likely because they were destroyed. All archaeological sites in Brazil struggle with preservation issues. Even at the Serra da Capivara National Park, in Piauí’s hinterland, which is the country’s most well-known group of rock paintings, faces enormous preservation challenges to this day. So imagine in São Paulo, an extremely urbanized state, which is the largest consumer of materials for civil construction and a supplier. It is a state that uses its own territory as raw material. There is an unbalanced conflict between the construction of cities and preservation. To obtain environmental permits for projects, you are required to have a archaeological research. So, there is a paradox in the activity of young archaeologists who find job opportunities in licensing companies. On the one hand, archaeological research can “approve” a particular project but can also resist mining and urbanization.

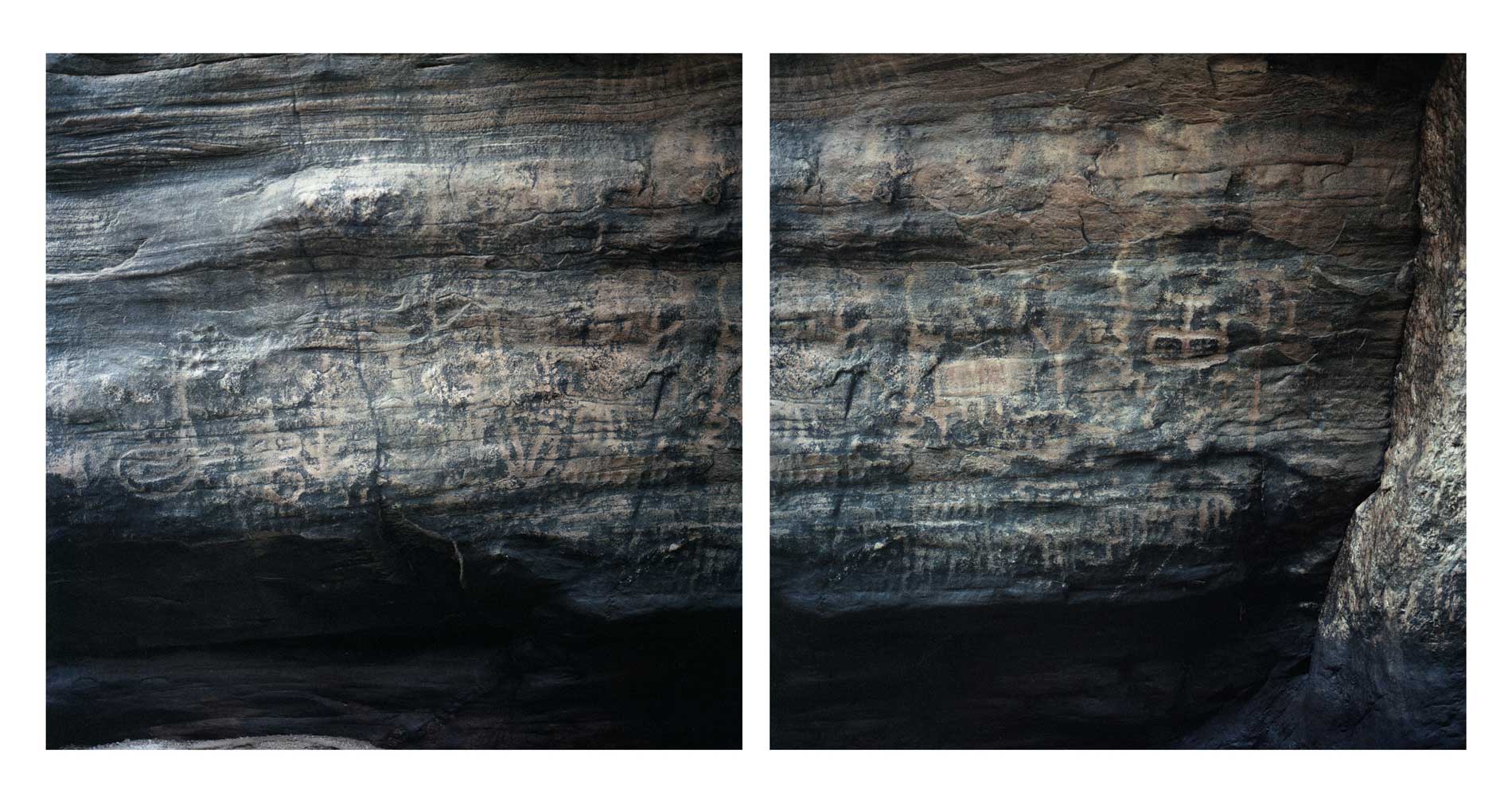

Valentina Tong, Cânion dos Apertados I and II, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 15 x 20 inches. UV printing on glossy EVA. Courtesy of the artist.

Valentina Tong, Mina Brejuí, 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 19 x 25.5 inches. UV printing on silver TNT. Courtesy of the artist.

AL: I was about to comment on your process, which is that photography initiates a connection with networks that are not necessarily linked to the realm of images. You get involved with a series of professionals from other fields and backgrounds that are not necessarily linked to the field of visual arts. So, I would like to ask you, how do you prepare yourself, and what is your daily life like in terms of engagement with these networks for the advancement of this work?

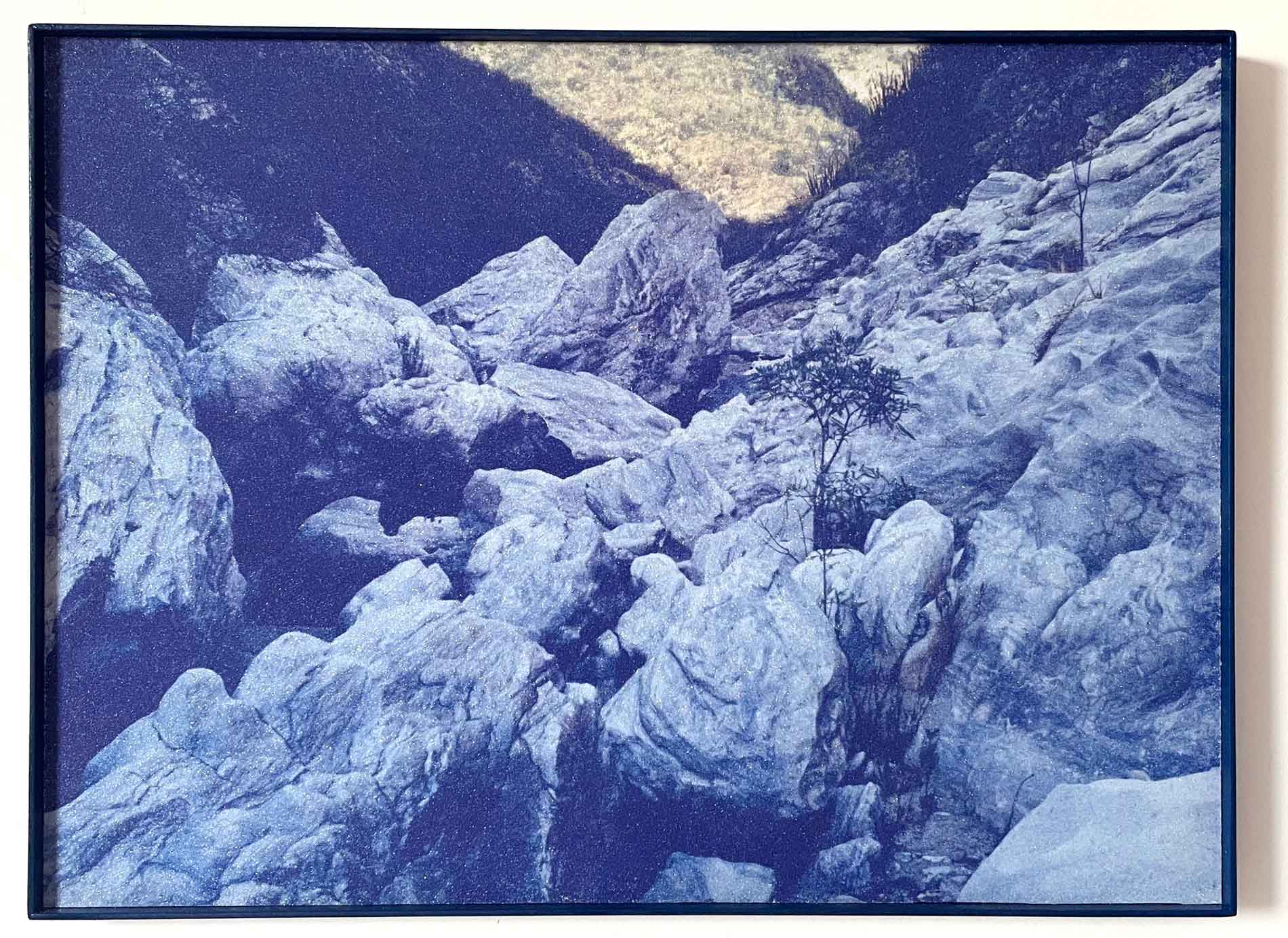

VT: I would say that the most challenging part of the job is to weave this network that will embrace the project and facilitate access to carry out the expeditions. I always do a lot of research before embarking on a trip, and it has been very enriching to expand my network with archaeologists, geologists, and people who work in mining. It’s a project that makes me navigate between different perspectives, sometimes opposing on the value of this heritage. I am still structuring myself as an artist because I have dedicated myself to curating for many years. Funding for these expeditions is still challenging; I try to participate in residencies and open calls for proposals to finance these projects. I managed to develop some chapters, for example, the expedition in the backcountry of Rio Grande do Norte, documenting the Seridó Geopark. I connected with the people responsible for creating the Geopark, generating meaningful conversations to understand the the geological formation of the territory.

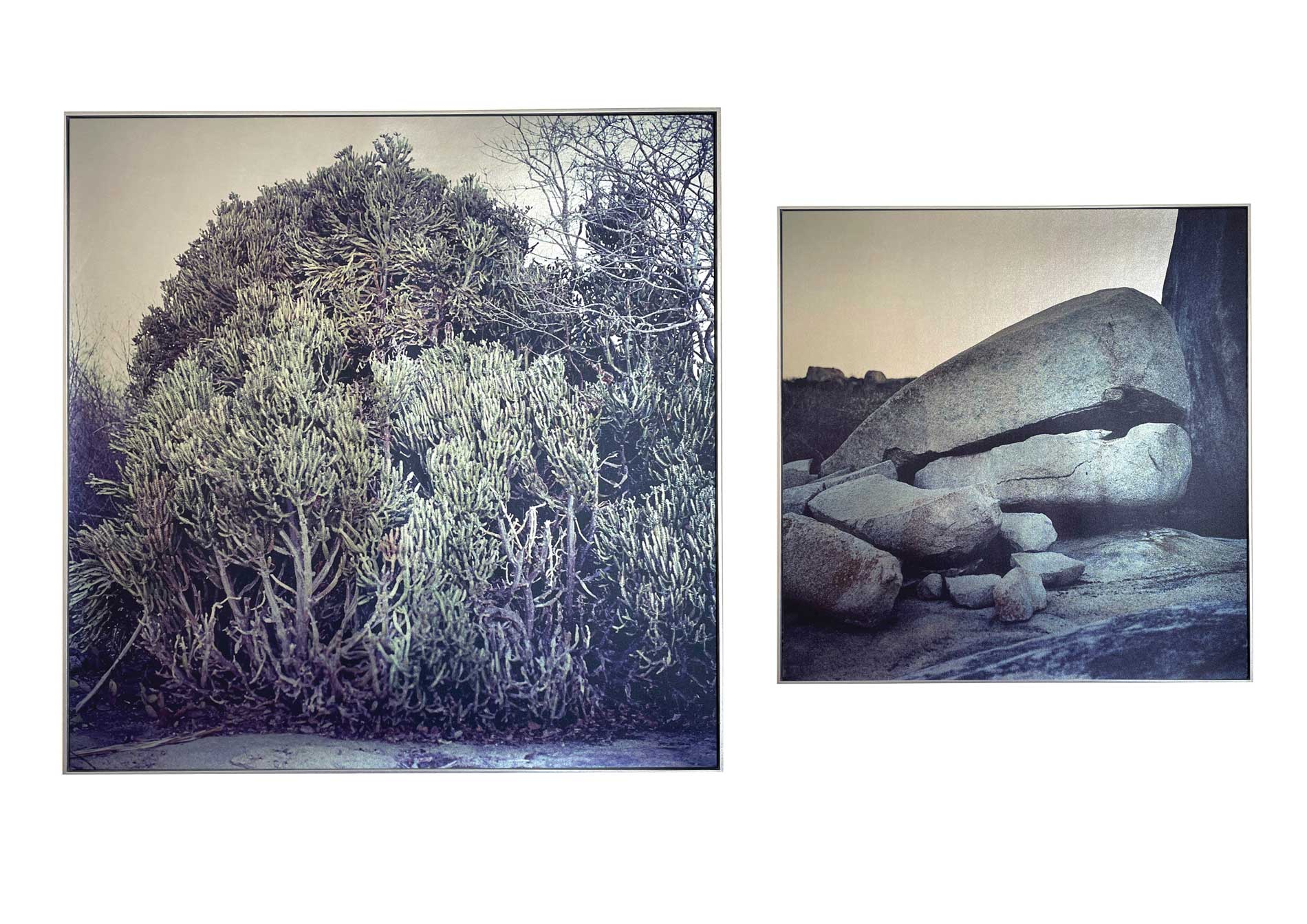

Valentina Tong, Serra Verde I e II (diptych), 2023, Seridó Potiguar, 23.5 x 23.5 inches and 17.5 x 17.5 inches.. UV printing on silver cedar fabric. Courtesy of the artist.

Valentina Tong, Cachoeira dos Fundões (diptych), 2021, Seridó Potiguar. Courtesy of the artist.

AL: Very interesting. While you were speaking, I couldn’t help but wonder if you’re in the process of compiling all this gathered information into a comprehensive database.

VL: I would love to create a database. Thinking about images associated with metadata would be very interesting because there is a documentary and historical aspect to recording a landscape in rapid disappearance. I photographed a quarry of columnar basalts for the Pedra Paulista project during my residency in Botucatu. I had to go back to reshoot some photos, and they told me it had been blasted. It’s an amazing place, a rare formation in Brazil, that is being blasted and turned into asphalt. So, we are talking about a photograph of something that is no longer there. I have visited several geological and archaeological sites in Brazil. I see it as a long-term project and would like to gather “data” from the images, whether geolocation, geological structures, archaeological information, or anything that can add to that image. I think it could be an interesting database for research, even if it’s not scientific research, or even if the images are strange and “unusable,” initially, in the fields of archaeology or geology. There is an intention to build bridges between these fields and languages.

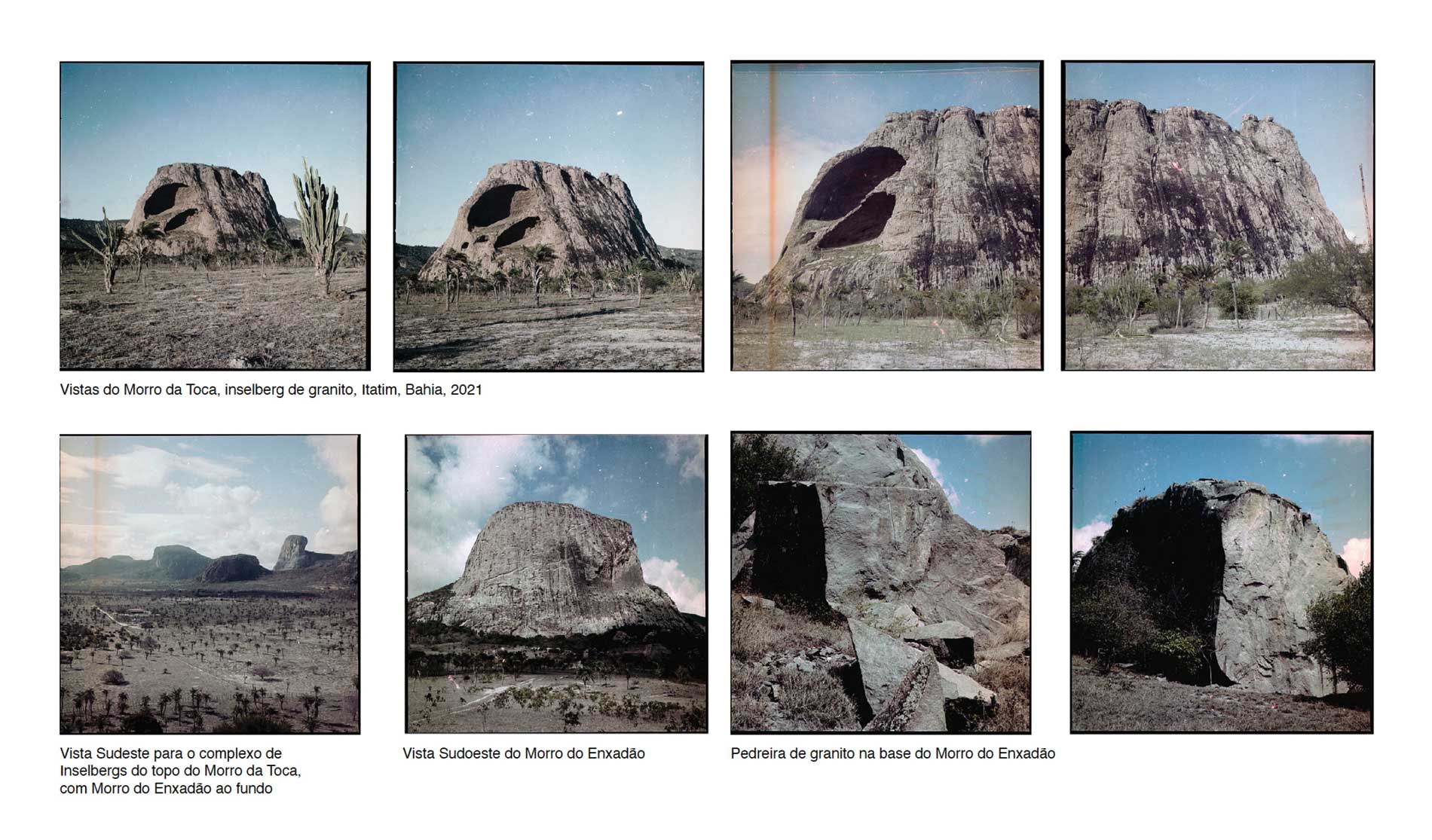

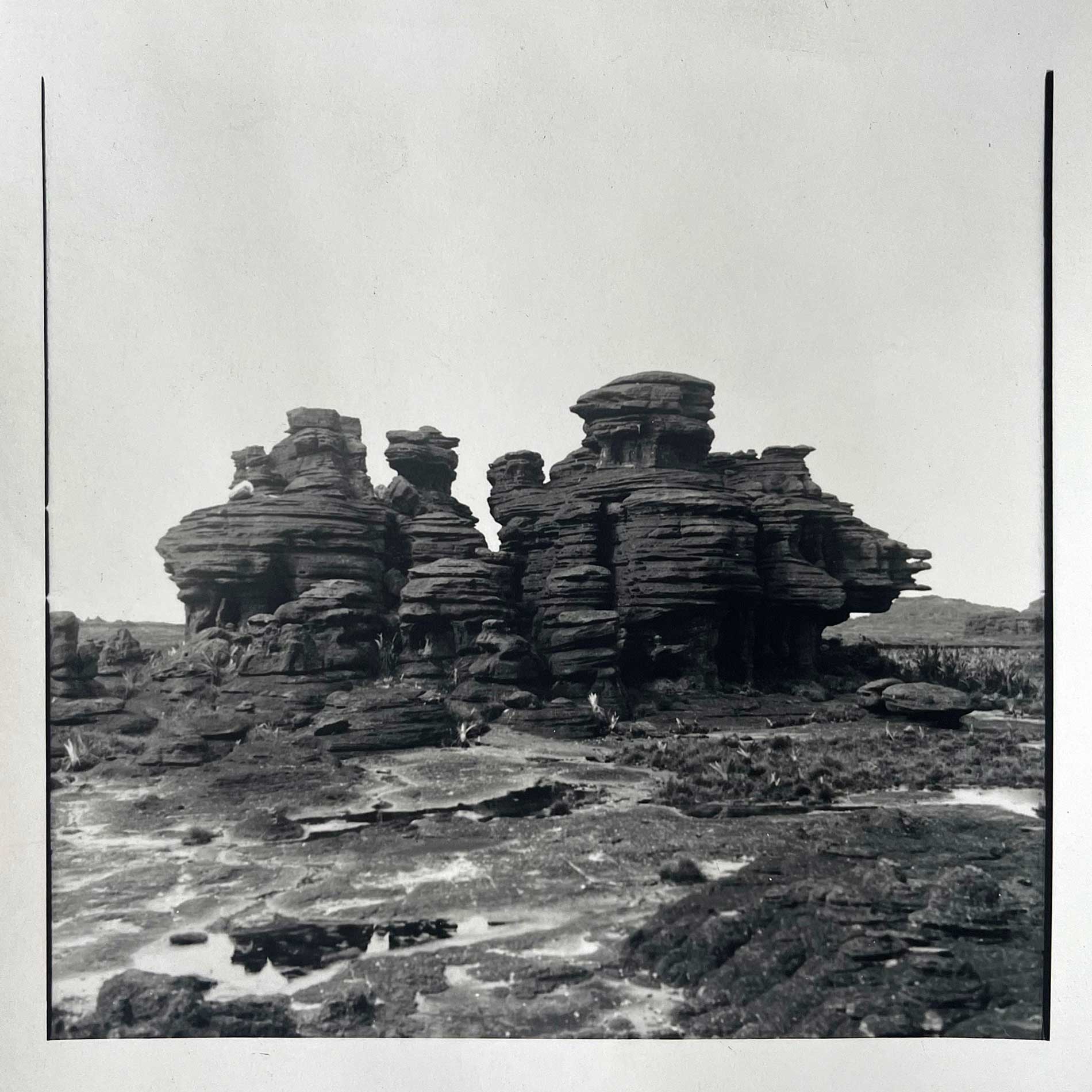

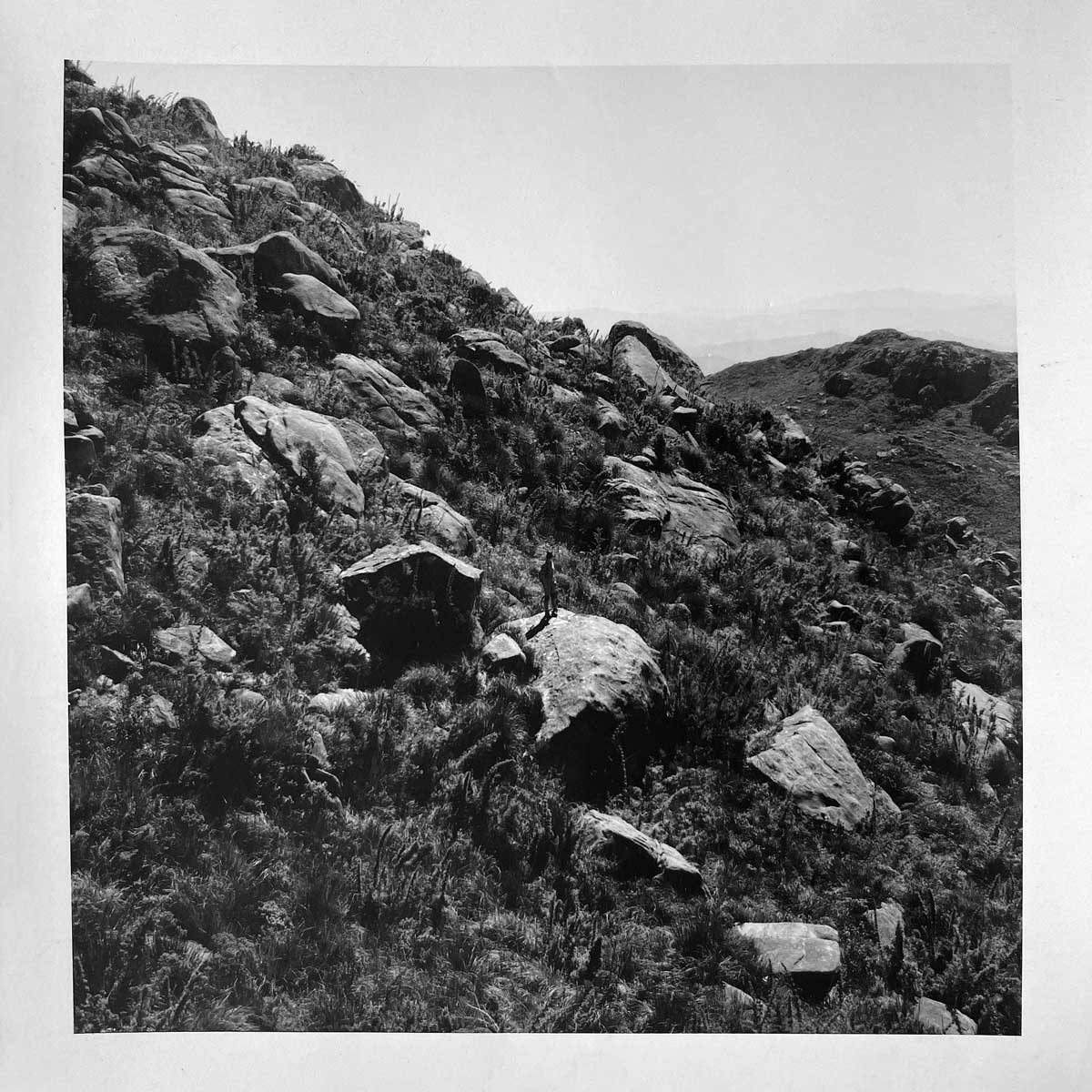

Valetina Tong, Itatim, Bahia, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

AL: And how has living amidst the landscape altered your artistic expression?

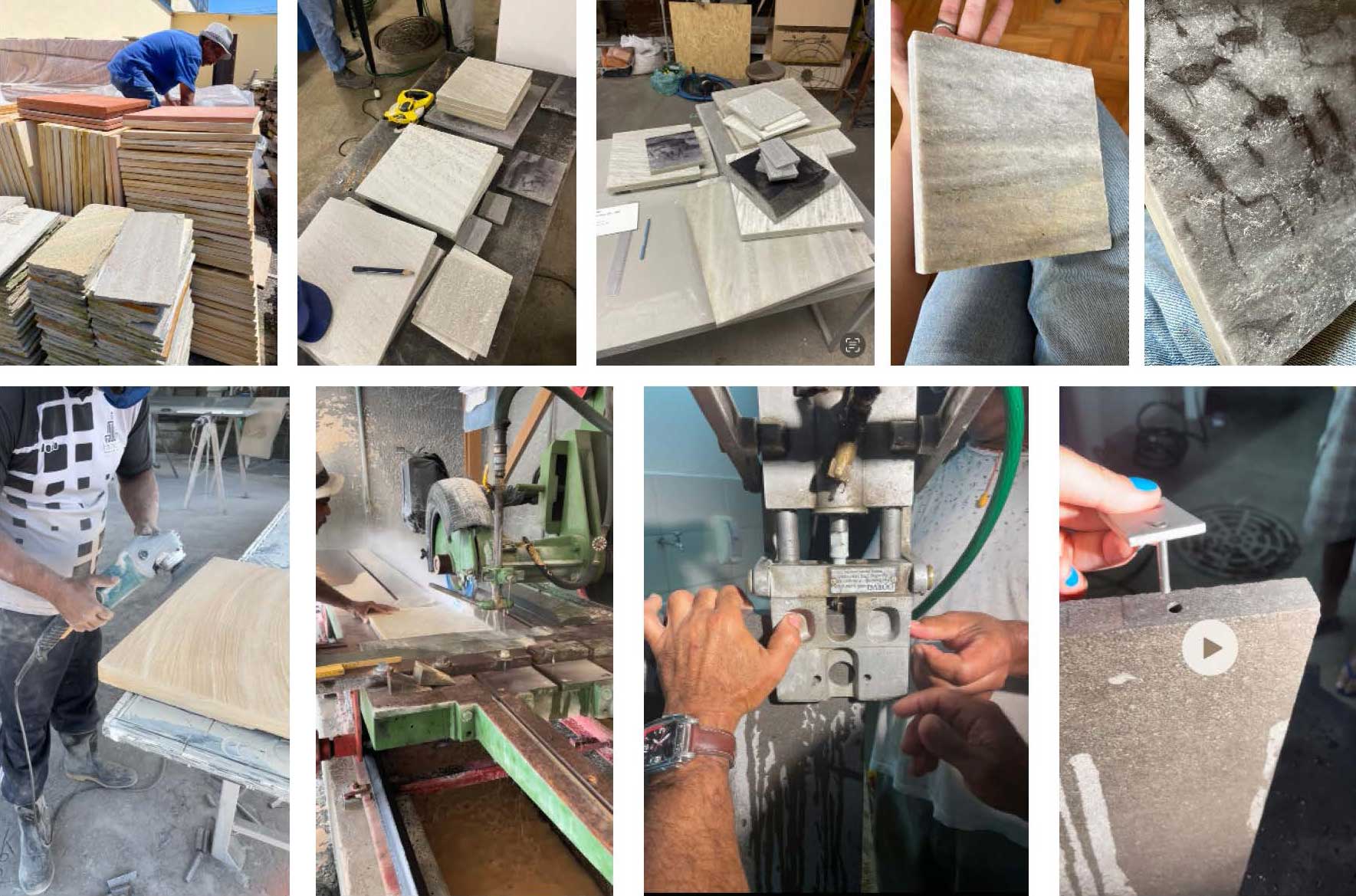

VT: Mainly I think I started more formally. My equipment hasn’t changed; I’ve been using my Hasselblad medium format with two backs, 6×6 and 4.5×6, for ten years. I used to buy black and white films because they were cheaper. I photographed Mount Roraima, Serra do Cipó, and Itatiaia subsequently using the darkroom to make gelatin and silver enlargements. Nowadays, I only use color film, some expired and I really enjoy the interventions and deviations they bring to the processes, both in the chemistry of development and in the scans I make myself. I am experimenting with digital printing methods and faster printing equipments used in commercial advertising, such as UV printing. I have also experimented with different supports like aluminum, metallic synthetic fabrics, and rocks, for example. I am creating sculptural objects that bring a bit of the physicality of the landscapes I have captured. This has changed significantly throughout the process, and I am increasingly eager to explore more of this tactile aspect of photography.

Valetina Tong, Monte Roraima, 2016, 2017, 6 x 6 inches, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

Valetina Tong, Parque Nacional do Itatiaia, 2017, 6 x 6 inches, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

AL: I want to take advantage of this discussion about the paths you establish to reach these places. Not only for planning purposes but also upon arriving at certain places or when building certain networks to access specific locations, you are proposing another way of looking at Brazil to those who follow your work. It’s another way to circulate within the Brazilian territory, and for me, this is very surprising because it’s not something I have observed so intensely in the work of other photographers, even those who photograph nature, for example. These professionals are more concerned with reaching their object, and what I noticed in your process is an observational dynamic that also considers the route as another element added to the work.

VT: I hadn’t thought about it objectively, but it makes sense in the history of this journey I started a few years ago. Just before the pandemic broke out in 2020, I went on a road trip across Brazil to photograph. I had already quit my job at the Instituto Moreira Salles, where I worked in curatorial projects, but kept some projects as a freelancer that helped with the costs of the trip. Geology wasn’t apparent in my head, it was deep (laughs). With the pandemic, it became impossible to maintain any plans. All National Parks were closed and everything with official structure shut down. I had to find alternative routes, allowing me to discover equally wonderful places that don’t have the proper institutional protection. A striking example was Itatim, in Bahia, a stunning region of inselbergs with many archaeological sites amid explosions from granite quarries. It was a new way of traveling, an unfolding of the journey itself. My great desire is that people become interested in making these journeys and that my photography becomes a guide that inspires a desire to explore our geological and archaeological heritage.

AL: How do you perceive our relationship with archaeological and geological heritage? Since we’re talking about heritage, a word with its problems, especially within the political context of Brazil, a country forged through exploitation, destruction, and extraction. Throughout the colonial process, we lost various forms of life, both plant and mineral. Heritage also relates to how we deal with, construct, and elaborate notions of a collection. You worked as a curator in an institution that engages in significant discussions about archiving, collections, and heritage. How do you handle your archive?

VT: It’s an ongoing, complex, interesting, and changing work, but primarily collective. I believe it should be collective. From the beginning, from research to photographic expeditions and editing, I seek to bring more perspectives on what that image represents. My work does not yet constitute a formal archive. The images are with me, and I am still reflecting on how to transform it into a collection. I want it to be an available, collective material that can aggregate information from various areas such as archaeology, geology, art, language, and image studies. I think this creates different views, not just my vision of a particular heritage. It’s indeed an exciting challenge of how to reintroduce this image into circulation, specially because it speaks of a record of archaeological heritage that has a relationship with the territory and the history of the native peoples who inhabited and still inhabit these landscapes. It was very important to me that the photographic installation I developed for MUBE (Brazilian Museum of Sculpture and Ecology) about the Serra da Capivara could be seen there. Today it is part of the collection of the Fundação do Museu do Homem Americano (Foundation of the Museum of American Man) and is on display within The Serra da Capivara National Park, in Piauí.

Valentina Tong, Toca do Mulungu, 2017/2023, Serra da Capivara, 14.5 x 14.5 inches. UV print on quartzite.

Collection of the Fundação Museu do Homem Americano (São Raimundo Nonato, Piauí). Courtesy of the artist.

View of the photographic installation at the exhibition Pedra viva: Serra da Capivara: o legado de Niéde Guidon,

at the Museu Brasileiro da Escultura e da Ecologia (São Paulo, 2023). Photo by Filipe Berndt.

Research on granite and basalt printing for the photographic installation Serra da Capivara, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

AL: When you think about the collective, do you feel that this work also evokes a sense of public heritage?

VT: Definitely. I see these places where I am photographing as public heritage. There is the cultural and archaeological heritage that is already protected by IPHAN (The National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute), but some are not. I encounter many difficulties in accessing rock paintings and engravings that are mapped out but located on private properties. We don’t know exactly their state of preservation. For me, rocks and quarries are considered heritage in the sense of territory. The rock as ground and matter, not as private property. Even though a company can hold the rights to extract rocks at a specific place, I document them as ancestral geological landscapes. So, I think this aspect is present in the work and that’s why I often find it challenging to photograph extraction and mining. It requires a lot of pre-research and building a dialogue with people working in mining who are opening doors for me to document these activities. These are private territories and activities with very well-protected access.

AL: It’s a systemic characteristic of how Brazil is articulated. This is not only true in Brazil but worldwide, where the mining industry is wrapped in protectionism, which creates barriers to specific access. For example, when I visit Minas Gerais, and the airplane is descending at Confins airport, one of the things that draws my attention is the remnants of those holes that mining has created over the decades. I reflected on this before I met you but when I saw the quality of the work you are developing, it brought me to a broader political reflection on what this type of intervention means. It’s as severe as the deforestation process in the Amazon region. There’s a parallel, not only in terms of violence but also in the type of modification of spatial reality. It’s this kind of dimension that perhaps leads me to a similar reflection to the one we did together when visiting Botucatu, which was precisely the relationship and reflections you made about the process of the formation of these rocks, the dynamics of geological eras, and this connection with the formation of the universe. Someone reading this conversation outside of Brazil, or even here, might not fully understand what we’re talking about.

VT: My perception is that I know very little about the Brazilian territory (laughs). But from what I’ve learned in research, Brazil has impressive geodiversity. We have various types of rock formations that led to different kinds of occupations. But the main thing is understanding that these rocks are millions, or even billions of years old. And this geological scale is difficult to comprehend. Basalt, for example, which is this rock I am documenting in the state of São Paulo, is magma that stemmed from the Earth’s interior and quickly cooled on the surface. It’s different from granite, which cools inside the Earth and emerges on the surface through erosion processes. These rock slabs we have on the coast of São Paulo, or the rock slabs in the hinterland of Paraíba, with wonderful granite boulders. There is a difference between igneous rock and sedimentary rock, which forms from the deposition of sediments. For example, the Serra da Capivara is a sandstone formation, an overlay of sediment layers of millions of years. The interior of São Paulo, which was this great desert in ancient history, also has a lot of sandstone, which is extracted in the tonnes for construction. I find it interesting to understand how the economic vocation of the territory is intimately linked to its geological formation. In the Cariri region of Ceará, for example, there is a large extraction of Cariri Stone, where Pleistocene fossils are daily found encrusted in the rocks. This region was a vast sea that turned into rock, exported throughout the country. In Minas Gerais and Bahia, the tectonic movement that formes the Cordilheira do Espinhaço, an unique mountain range formation we have in Brazil, constitutes a large chain of highly active quartzite extracted as ornamental rock. In the architectural market, these rocks are called “exotic” and are highly consumed in the United States to where tons of Brazilian rocks are exported to. This is a new phase of the research I am doing. I ended up learning a lot about economic activities and the companies I have to look for. This research led me to the understanding of the Geology graduation in Brazil, which educates young people who will work for these large companies. They learn to locate, extract, and process materials. For me, the work must be articulated with this other end. There is the preservation end, but there is also the extraction economy. So, it’s a middle ground of how I navigate between these parts to make the work possible.

Valentina Tong, Cariri, 2021 Courtesy of the artist.

AL: Yes, that demands a lot from you as a person, right?

VT: I find it interesting to engage with people who are involved in extraction. Recently, I attended the Cachoeiro Stone Fair, a trade fair for the commercialization of rocks and extraction technologies in the interior of Espírito Santo, where the largest ornamental rock processing hub in Brazil is located. I think it’s essential to open up this dialogue. I feel that people are also interested in my work, which is not exactly a denunciation. My work is a visual reflection of these transformation processes because, in the end, we are the destruction. We are consuming all the mining, using rocks, building cities, and consuming batteries. Thinking about this new geological era called the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, and Plantationocene, there is a current discussion about collectively living in a transition of geological eras. We are inaugurating the era of the ability to alter a geological landscape through its consumption.

AL: I thought about the Terrane process, my project with the women who build cisterns, whom we call “women quarry workers.” The term “earth” comes from geology and is related to a type of rock that moves from its place of origin and affects the destination without necessarily losing its original characteristics. These women travel through the Brazilian semi-arid region, which has the Caatinga as its primary biome in a very symbolic and acute drought process, to build water tanks. They end up changing the landscape without losing, in a way, their original characteristics. They become articulators, sometimes leaving their states to develop this type of work, which stems from this geological term and has become a poetic concept in my case. I wanted to discuss this articulation of work that also produces action. The fact that people are interested in the type of work you do and that you articulate this dialogue changes how they see the process. By proposing a way for workers to look at their own activity, you are also proposing a modification. Do you feel that this type of intervention is part of the development of your poetics as an artist? Or is it also a work that comes from your experience as a curator?

Ana Lira, Terrane, image from the Artist Book, 2018. Courtesy of the curator.

VT: I don’t think about that differentiation much. I am interested in the processes and dedicate time to understand it. I don’t know if it’s a transformation for the people I encounter, but I am already expanding a network of collaborations that follow my work and vice versa. There are discoveries on my part as well, not scientific ones but I am happy to share. I think there is a transformation as a process of collective work. This has already opened my mind a lot about how to approach these places, understanding the complexity that is the history of extraction. The richest exchange for me has been with archaeologists. It is interesting to see how the stories are similar, solitary and collective struggles, usually women committed to some archaeological site, bravely fighting for the preservation and documentation of disappearing heritage: Niéde Guidón and Gisele Felice in Serra da Capivara, Edithe Pereira in Monte Alegre, Pará, Marília Perazzo in the State of São Paulo…

AL: Why do you think photography is still the best way to respond to the process of this work when, from my point of view, it has so many layers and is much more complex than, at least, I understand the field of photography can deal with and respond to?

VT: Because photography is my language. It always has been. From a very early age in architecture school, my research was photographic. I studied the theory and history of photography in a non-formal way. I grew up looking at photographs because of my mother, who is a photographer. Curatorial work at the Instituto Moreira Salles was an immersion in the work of other artists who are producing today using the photographic media. This dialogue with all the artists I worked with was also fundamental to my practice. Before, I resisted the idea of being an artist and curator. Nowadays, I embrace it much more generously, trying to bridge that gap. When I am alone shooting on expeditions, I am whole and focused. Now, the developments it can bring beyond the image, that’s when I bring in other people to read, I bring you, geologists, archaeologists… But my contribution is photographic.

AL: Amazing! I really enjoyed having this dialogue with you. I think we covered a lot of important ground.

VL: Same here. Thank you so much Ana Lira.

Expedition to the granite inselbergs region in Itatim, Bahia, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Valentina Tong and Ana Lira with the archaeology team on the expedition to the rock art site in the countryside of São Paulo, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

To know more about Valentina’s work acesse: https://valentinatong.com/viagemgeologica/ // @valentinatong @sau_va. To learn more about Ana Lira: @anaretratografia.

Hero image: Photographs of the series Viagem Geológica, 2020-23. Courtesy of the artist.