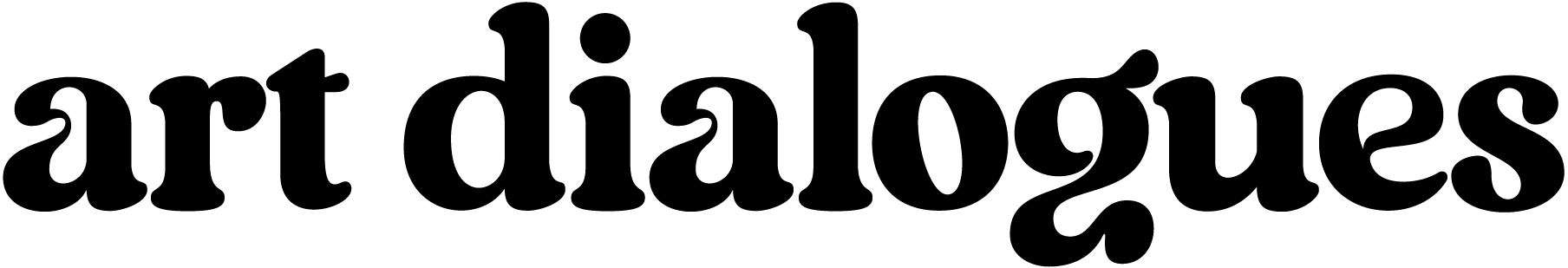

My studio is at Silver Arts Project in 4 World Trade Center. I call it “the corner office.” With these big windows that look out onto the Hudson River, it’s as if I can step out into the sky. I have a bed in the corner, which is my reading nook. There’s work on the floor where I’m making and building my fiber compositions, and the rest of the studio has work hanging on the wall.

Most people from Southern India have an innate relationship with handloom fabric because there’s so much of it every day. I am thinking about my mother’s saris and my father’s veshtis. Wearing these garments requires a literacy with pleating and folding cloth. I can picture my grandmother washing her nine-yard sari in our apartment in Chennai (Madras). She would fold the cloth precisely, throw it over a clothesline hung high up with a long stick and use the tool to methodically unfold it out to dry.

I was eleven years old and living in Dubai with my parents, when I left to study at a residential school in India called Rishi Valley. At school we swept our floors daily with an Indian-style broom, and squatted to mop with a cloth. We washed our clothes, socks, and undergarments on washing stones by hand. I bring all of this work into my artwork. It was at Rishi Valley that I also started to think about textile as artwork.

I was obsessed with Gauguin in school, before I understood the broader context of his work, and also the Group of Seven from Canada—artists who were thinking about color and movement.

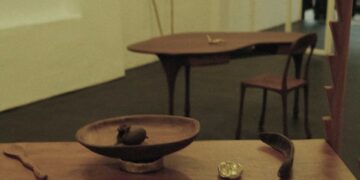

In batik*, the image slowly emerges in reverse, because you start by blocking off the white parts of the fabric with wax, then yellow, green, all the way to black—you progressively go from light to dark colors. With my feltmaking process, I make the work upside down. So I create the compositional part of the face first and then build the body of the textile in reverse. I enjoy holding the composition like a puzzle in my head, the unknown of felting it and flipping it over and then cutting it open, letting it slowly reveal itself. There’s a relationship between batik and feltmaking in this way.

I lay the wool down like I’m sketching—I cross-hatch the wool, overlapping it to form a mesh, a strong connected membrane. In batik, specifically in the style that I practiced, wax brushstrokes are a form of markmaking.

That’s the relationship between the two: the gesture and color too. At school, it was complicated for our teacher, Manoranjan Sir, to explain dyeing to us. So he would mix dyes and we would paint. These days I mix my own formulations. Oftentimes you are looking at a color that will not be the final tone, because it has to be treated with another solution for the true tone to pop. There’s a sense of transformation as I lay fiber down for felt, too—there’s an alchemy to it. It changes in its final form. And then there’s the relationship of fluid and fiber when I wet the wool. I rub it and roll, and rub it over and over.

My interest in cooking helped me learn how to dye and follow a recipe, rewriting it step by step. I tell my students at Pratt, “If you like to cook, you’ll be a good dyer. If you like dyeing, you will become a better cook.” And with wetting the wool—it’s sheep hair, right? You need to let it really impregnate the fiber. I can feel it tighten under my fingers as it felts, it feels alive.

Also, it’s very process heavy. I have to understand the physics of fiber, the chemistry of color. In that way, my work is essentially a research project, starting with a question. And then that answer leads to another question.

Someone asked me in an interview, How do you feel working with such humble materials? And I thought, These are not humble materials! They’re high quality. They come from sheep and are renewable— they’re like jewels. In my studio I feel like I’m surrounded by rubies and emeralds, treasures from the earth. It’s difficult to make something uninteresting when my starting point is so rich. I like the word terroir — just like wine, wool is informed by the soil the sheep grazes on, the moisture levels. Its habitat gives it perfume and flavor.

My network of wool suppliers is constantly shifting and expanding. Each variety of wool has its own texture, which lends itself to a unique handwriting in the work. There’s a beauty of working with material from its source. If you’re really paying attention as you work, you naturally wonder how the material came to be in its present state, and what it was before, where it is from. Even with dye, what is the chemical formulation? What impact does it have in its afterlife? It is a general sensitivity to the origin of things that one engenders.

This artist statement is a segment of the discussion involving Sagarika, Andrew Gardner, Bahauddin Dagar, and Vyjayanthi Rao, contributing to the catalog we collectively crafted for her exhibition at Palo Gallery in 2023.

To know more about Sagarika: https://www.sagarikasundaram.com/ / @ohsagarika

Photos: Anita Goes

*Batik: a method (originally used in Java) of producing colored designs on textiles by dyeing them, having first applied wax to the parts to be left undyed.